Timeline of plesiosaur research

This timeline of plesiosaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation,

Early researchers thought that plesiosaurs laid

Prescientific

Associated remains of plesiosaurs and animals like the diving bird Hesperornis or the pterosaur Pteranodon may have inspired legends about conflict between Thunder Birds and Water Monsters told by the Native Americans of Kansas and Nebraska.[11]

18th century

- William Stukeley described the first partial skeleton of a plesiosaur, brought to his attention by the great-grandfather of Charles Darwin, Robert Darwin of Elston.[12]

19th century

1810s

- Mary Anning discovered some plesiosaur fossils in England.[1]

1820s

- Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus.[13]

- Parkinson coined the name Plesiosaurus priscus for some of the remains used by de la Beche and Conybeare as the basis for Plesiosaurus. This species is currently regarded as of dubious taxonomic value.[14]

December

- Mary Anning discovered a nearly complete Plesiosaurus skeleton near Lyme Regis. This specimen would later be catalogued as BMNH 22656.[15]

c. December

- Around the same time as the discovery of BMNH 22656, another Plesiosaurus specimen was discovered at the same site. The specimen was donated to the Oxford University museum and is probably the specimen known today as OXFUM J.10304.[16]

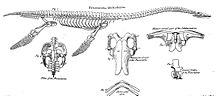

- Conybeare described the new species name Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus for the Plesiosaurus discovered by Anning. As the first species name given to a distinctive and well preserved Plesiosaurus skeleton it has come to be regarded as both the type specimen of Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus specifically and of the genus Plesiosaurus as a whole.[15][17]

- Mary Anning collected the Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus specimen now known as BMNH R.1313.[18]

1830s

- Buckland in Conybeare described the new species Plesiosaurus macrocephalus.[19]

- De la Beche illustrated a work titled "Duria Antiquior", meaning "A More Ancient Dorset" for fossil hunter Mary Anning. This work, which prominently features plesiosaurs, has been regarded as the first attempt to accurately reconstruct the Mesozoic world through an artistic medium.[3]

- von Meyer described Pistosaurus. Pistosaurus is believed to be a transitional form linking plesiosaurs to their basal sauropterygian forebears.[20]

1840s

- Owen described the species now known as Thalassiodracon hawkinsii.[21]

- Owen described the new species Polyptychodon interruptus.[19]

- pliosaurs.[22]

- Stutchbury described the species now known as Atychodracon megacephalus.

- The trustees of the British Museum of Natural History bought the type specimen of Plesiosaurus from the estate of the first duke of Buckingham, Richard Glenville. The museum catalogued the specimen as BMNH 22656.[16]

1860s

- Carte and Bailey described the species now known as Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni.[19]

- ichthyosaur in Journey to the Center of the Earth.[23]

- Owen described the species now known as

- Seeley described the species now known as Microcleidus macropterus.[19]

- Owen described the species now known as Archaeonectrus rostratus.[19]

- An army surgeon named Dr. Theophilus Turner discovered the fossils of a large animal in the Pierre Shale of Kansas, USA. The remains represented the first nearly complete plesiosaur specimen from North America. Turner gave some of its vertebrae to a member of the Union Pacific Railroad's survey named John LeConte. LeConte sent the vertebrae to Edward Drinker Cope for study. Cope recognized the find as a significant plesiosaur discovery and wrote to Turner asking him to excavate and ship the fossils to him.[24]

March, mid

- Cope erected the new genus and species Elasmosaurus platyurus for the fossils sent by Turner in a rushed descriptive manuscript written within two weeks of obtaining them.[25]

March 24

- Cope presented his findings regarding Elasmosaurus to a meeting of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[26]

- Cope described the new species Elasmosaurus platyurus.[19]

- Cope's description of Elasmosaurus was formally published.[26]

September

- William E. Webb and others collected and shipped a plesiosaur specimen to Cope.[27]

- Seeley described the species now known as Peloneustes philarchus.[19]

- Cope named the plesiosaur specimen collected by Webb Polycotylus latipinnis.[27]

August

- Cope prepared a preprint for the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society of his Elasmosaurus description, including reconstruction of the animal with a short neck and very long tail. The manuscript was then distributed to other scholars.[26]

1870s

March 8

- Cope's mentor Joseph Leidy gave a presentation reporting his recent discovery that Cope's reconstruction of Elasmosaurus positioned the skull at the end of the tail rather than the end of the neck.[26]

- Leidy's discovery embarrassed Cope, who began spreading notice of an unspecified error in his Elasmosaurus description with an offer to replace it with a corrected version and its second volume.[28]

November

- O. C. Marsh collected a better an additional specimen of Polycotylus in Kansas that was better preserved than the type described by Cope. The specimen is now catalogued as YPM 1125.[29]

- Phillips described the species now known as Pliosaurus macromerus.[19]

- Phillips described the species now known as Cryptoclidus eurymerus.[19]

- Cope described the species now known as Hydralmosaurus serpentinus.[19]

- Cope inaccurately referred to Polycotylus as "the first true plesiosauroid found in America."[27]

- Cope imagined elasmosaurs feeding by craning their necks above the water and striking downward at fish long distances from their bodies.[30]

- B. F. Mudge discovered ten articulated vertebrae in the Fairport Chalk of Kansas that he mistook for ichthyosaur remains. These fossils are now catalogued as KUVP 1325.[31]

- Sauvage described the new species Liopleurodon ferox.[19]

- Joseph Savage discovered a second, better preserved Trinacromerum "anonymum" in Kansas.[31]

- Hector described the new species Mauisaurus haasti.[19]

- Seeley described the new species Muraenosaurus leedsi.[19]

- B. F. Mudge discovered fragments of a large elasmosaur skeleton in the Fort Hays Limestone of Kansas.[32]

- Mudge and Williston excavated the remains another large Kansan plesiosaur, this one from the Smoky Hill Chalk.[32] The specimen may be a Styxosaurus snowii and is currently catalogued as YPM 1644. It was the first plesiosaur Mudge had ever found with gastroliths and the first plesiosaur encountered by Williston in general.[33]

- Hector reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in New Zealand.[34]

- Seeley published a paper intended to help improve the state of science's understanding of plesiosaur shoulder girdle anatomy, which had been muddled by the poor preservation of the fossils many early paleontologists had to rely on for their observations.[35]

- Cope once more portrayed elasmosaurs as feeding by fishing from a distance with heads held above the waterline.[36]

- Blake in Tate and Blake described the new species Plesiosaurus longirostris.[19]

- Simolestes indicus.[19]

- Mudge discussed the gastroliths of YPM 1644 in a scientific publication.[33] He concluded that plesiosaur exploited gastroliths to assist in breaking down food the way many modern birds and reptiles do.[37]

- Lydekker described the species now known as Cryptoclidus richardsoni.[19]

1880s

- Oxford acquired the Misses Philpot collection, which included the type specimen of Plesiosaurus macromus. The museum catalogued this specimen as OXFUM J.28587.[38]

- Sollas described the species now known as Attenborosaurus conybeari.[19]

- The British Museum of Natural History purchased the Edgerton collection, which included the complete Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus jaw now known as BMNH R.255.[18]

Spring

- The Smithsonian bought a partial plesiosaur skeleton from Charles Sternberg. The specimen is now catalogued as USNM 4989 and would later serve as the type specimen of the new genus and species Brachauchenius lucasi.[39]

- Harry Seeley mistakenly claimed to have discovered several fossil plesiosaur embryos.[40]

- Trinacromerum bentonianum from Kansas.[41]

1890s

- In an article published in the New York Herald, Marsh brought up Cope's anatomic reversal of Elasmosaurus.[28]

- E. P. West excavated a skull and partial neck belonging to the elasmosaur that would come to be named Styxosaurus snowii. The specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 1301.[42]

- Williston described the species now known as Styxosaurus snowii.[19]

- Seeley described the species now known as Muraenosaurus beloclis.[19]

- Marsh described the new species Pantosaurus striatus.[21]

- Charles H. Sternberg obtained two large elasmosaur vertebrae that would later serve as the type specimen of Elasmosaurus sternbergi. The specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 1312.[43]

- F. W. Cragin discovered a partial plesiosaur skeleton and associated gastroliths in what is now recognized as the Kiowa Shale. This specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 1305 and would later be named Plesiosaurus mudgei.[44]

- Williston argued that plesiosaurs ingested gastroliths only accidentally or to relieve "food craving[s]".[37] However, he also observed that the rocks used as gastroliths were more similar to rocks 400–500 miles away in Iowa or the Black Hills of South Dakota than those of the local geology.[45]

- Cragin described the new species Plesiosaurus mudgei for KUVP 1305.[44]

- Dames described the species now known as Seeleysaurus guilelmiimperatoris.[19]

- With guidance from

- Knight described the new species Megalneusaurus rex.[19]

- A man named Andrew Crombie discovered a fossil jaw fragment with six teeth in Queensland, Australia. The specimen would become the type for the genus Kronosaurus.[47]

20th century

1900s

- Knight described the species now known as Tatenectes laramiensis.[21]

- George F. Sternberg discovered the plesiosaur specimen now known as KUVP 1300 that would later serve as the type specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni.[48]

- Williston described the new species Dolichorhynchops osborni.[19]

- Williston made several changes to plesiosaur taxonomy. One of these was the description of the new genus and species Brachauchenius lucasi, whose type specimen was a partial skeleton discovered in Kansas. This specimen is now catalogued as USNM 4989.[39] He also described the new species Trinacromerum anonymum based on the vertebral series discovered by Mudge in 1872. This specimen is now known as KUVP 1325.[31] Lastly, Williston regarded Plesiosaurus mudgei as a junior synonym of the species Plesiosaurus gouldii.[44] He also commented on the ongoing debate regarding plesiosaur gastroliths, acknowledging the possibility that they were used for ballast while also maintaining openness to his 1893 suggestion that the stones were ingested accidentally.[49]

- teeth to do that job for them.[49]

- Harvard paleontologist Charles R. Eastman, "offended" by Brown's claim that plesiosaurs had a gizzard, criticized the idea in print.[49]

- Williston responded to Eastman, reasserting the evidence for plesiosaur gastroliths by noting that by this time at least 30 specimens containing them had been found.[50]

- Williston described several new taxa and specimens. One of these was the new species

- Williston reported the discovery of another Brachauchenius specimen, although this one was discovered in Texas.[51]

- Williston argued that Brachauchenius lucasi was closely related to Liopleurodon ferox.[52]

- Andrews described the new species Tricleidus seeleyi.[19]

- Watson described the new species Sthenarasaurus dawkins.[19]

1910s

- Fraas described the species now known as Rhomaleosaurus victor.[19]

- Andrews described the species now known as Leptocleidus capensis.[19]

- Brown described the new species Leurospondylus ultimus.[19]

- Williston criticized portrayals of long-necked plesiosaurs as having unnaturally flexible necks.[46]

- Wegner described the new species Brancasaurus brancai.[19]

- Williston observed that the semicircular canals inside a plesiosaur's ear were well developed, giving them a good sense of balance and coordination.[53]

- The Smithsonian obtained the Tylosaurus specimen with preserved polycotylid stomach contents from Charles Sternberg.[54] The Tylosaurus is catalogued as USNM 8898 and its last supper as USNM 9468.[55]

1920s

- Andrews described the new species Leptocleidus superstes.[19]

- Sternberg observed that being contained in the stomach of a mosasaur might have helped ensure the preservation of the polycotylid now known as USNM 9468 by protecting it from scavenging sharks.[55]

- Huene described the species now known as Hydrorion brachypterygius.[21]

- Kronosaurus queenslandicus based on the jaw fragment found there by Andrew Crombie in 1899.[47]

- George F. Sternberg discovered a third specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni in Kansas.[48]

- More Kronosaurus fossils were discovered in central Queensland near the site of the type specimen's discovery.[47]

1930s

- Swinton described the new species Macroplata tenuiceps.[19]

- George F. Sternberg and M. V. Walker discovered a well-preserved large elasmosaur specimen.[56]

- Harvard University dispatched a fossil hunting expedition to Queensland, Australia. In Army Downs they discovered a nearly complete specimen of Kronosaurus.[57]

- The "surgeon's photograph" of the mythical beast.[58]

c. 1935

- The University of Nebraska State Museum bought the elasmosaur specimen discovered by Sternberg and Walker in 1931. The specimen is now catalogued as UNSM 1195.[56]

- Russell described the new species Trinacromerum kirki.[19]

- A specimen of Trinacromerum was discovered in a roadside exposure of the Greenhorn Formation in Kansas. The specimen is now catalogued as KUVP 5070.[31]

- A large pliosaur skeleton was found on the banks of Volga River. However, the specimen was damaged during the excavation and only the skull and chest region were successfully extracted.[59]

1940s

- A complete specimen of Plesiosaurus conybeari, including preserved soft tissues, was destroyed in a bombing raid against Bristol. Fortunately, a cast of the specimen survived in the British Museum.[60]

- White described the new species Seeleyosaurus holzmadensis.[61]

- Cabrera described the new species Aristonectes parvidens.[19]

- Young described the new species Sinopliosaurus weiyuanensis.[21]

- Welles described the new species Hydrotherosaurus alexandrae.[19]

- Welles argued that plesiosaurs did have flexible necks after all.[36]

- Museum of Paleontology.[62]

- Riggs described the new species Trinacromerum willistoni based on the 1936 discovery KUVP 5070.[31]

- Pliosaurus rossicus.[59]

- Novozhilov described the species now known as Pliosaurus irgisensis.[19]

- Welles described the species now known as Libonectes morgani.[19]

- de la Torre and Rojas described the species now known as Vinialesaurus caroli.[21]

1950s

- Alfred Sherwood Romer helped mount the Kronosaurus discovered in Queensland by the 1930s Harvard expedition for the University's Museum of Comparative Zoology. The poorly preserved bones required a significant amount of plaster for the restoration, earning the specimen the mocking nickname "Plasterosaurus".[57] The final mount was 42 feet long, probably due to Romer overestimating the number of vertebrae in its spine; a more likely length is about 35 feet.[63]

- Fossil hunters Robert and Frank Jennrich serendipitously discovered a partial Brachauchenius skeleton when looking for sharks teeth.[52]

- Shuler, like Williston in 1914, found elasmosaurs to have relatively inflexible necks.stereoscopic vision, which would have been useful for hunting small prey.[53]

October

- George Sternberg excavated the Brachauchenius discovered by the Jennriches. This specimen, now known as FHSM VP-321, was both larger and better preserved than the Brachauchenius type specimen. Although it was put on display soon after discovery, it would not be described for the scientific literature for nearly 50 years.[52]

- Welles argued that the "Elasmosaurus sternbergi" type specimen was actually pliosaur vertebrae.[43]

- A private landowner in Kansas donated some Elasmosaurus vertebrae to the Sternberg Museum. These fossils are now catalogued as FHSM VP-398.[64]

1960s

- Tarlo described the new species Pliosaurus andrewsi.[19]

- Welles described the species now known as Callawayasaurus colombiensis.[21]

- Welles reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in South America.[34]

- Chatterjee and Zinsmeister reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in Antarctica.[34]

- Lambert Beverly Halstead Tarlo argued that long-necked plesiosaur flippers could only move horizontally, and while maneuverable, they were confined to surface waters by an inability to dive.[65]

1970s

- Beverly Halstead reclassified the Volga pliosaur, Pliosaurus rossicus, to the genus Liopleurodon.[59]

- Paul Johnston discovered plesiosaur fossils in a roadside exposure of the Greenhorn Formation in Kansas.[67] During the excavation the dig site was scouted by two suspicious men. After a break from digging the Johnston team returned to find all of the fossils crudely extracted from the rock except for a flipper that the team had reburied. Based on the flipper, the stolen plesiosaur could be identified as Trinacromerum bentonianum.[68]

- penguins.[8]

- Ochev described the species now known as Georgiasaurus penzensis.[19]

- Robinson publishes follow up research to her previous publication on plesiosaur locomotion.[9] This second paper notably concluded that plesiosaurs were incapable of leaving the water.[69]

1980s

- Dong described the new species Bishanopliosaurus youngi.[19]

- Michael Alan Taylor published a paper concluding that plesiosaurs would have been capable of moving on land after all because their spinal column was too arched for their lungs to collapse.[70]

- Brown described the new species Kimmerosaurus langhami.[19]

- Brown emended the species Plesiosaurus guilelmiiperatoris originally described by Dames in 1895.[15]

- Taylor argued that plesiosaurs used their gastroliths to adjust buoyancy or to help stay level and balanced while swimming.[37]

- Samuel F. Tarsitano and Jürgen Riess published a paper harshly critical of Robinson's previous work on plesiosaur locomotion. However, while criticizing Robinson's work they were reluctant to make any positive claims of their own, concluding that the details of plesiosaur locomotion were "unknown".[9]

- Richard A. Thulborn published the results of his recent re-examination of the purported plesiosaur embryos discovered by Harry Govier Seeley. Thulborn concluded that Seeley's supposed embryos were actually nodules of mudstone and shale derived from sediments that once filled in a crustacean burrow system and were not even animal body fossils.[40]

- Delair described the new species Bathyspondylus swindoniensis.[21]

- The partial remains of a large pliosaur, initially mistaken for a

- Zhang described the new species Yuzhoupliosaurus chengjiangensis.[21]

- A South Australian opal miner named Joe Vida discovered the skeleton of a juvenile plesiosaur whose remains had converted to opal. Its preparator, entrepreneur named Sid Londish bought the specimen and funded its preparation, but went bankrupt. When the specimen was put up for auction fear spread that a potential buyer might break the specimen down for its gemstone value. A television drive was arranged on behalf of the Australian Museum. The Museum succeeded in raising 340,000 dollars to buy the specimen, whose gemstone value was about $300,000. Eric was later identified as a specimen of Leptocleidus.[22]

- Wiffen and Moisley described the new species Tuarangisaurus keysei.[21]

- killer whales and probably ate larger, bonier prey.[51]

- Orville Bonner discovered a specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni that was later seen to preserve developing young inside it.[71]

- Judy Massare analyzed Mesozoic marine reptile swimming abilities and found that long-necked plesiosaurs would have been significantly slower than pliosaurs due to excess drag incurred from the length of the neck.[72]

- The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History acquired the Dolichorhynchops osborni specimen discovered by Bonner and catalogued it as LACMNH 129639.[44]

- Beverly Halstead published a paper suggesting that plesiosaurs swam using all four flippers paired with an undulatory motion of the body comparable to a sea lion's.[73]

- Nakaya reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in Japan.[34]

1990s

- The world's smallest plesiosaur, between four and five feet in length, was discovered near Charmouth on the Dorset Coast.[74]

- Sciau et al. described the species now known as Occitanosaurus tournemirensis.[21]

- Gasparini and Spalleti described the new species Sulcusuchus erraini.[21]

- Stewart noted a relative paucity of plesiosaur fossils from the lower portions of the Smoky Hill Chalk in a manuscript for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.[75]

- Tim Tokaryk of the Dolichorhynchops herschelensis near Herschel, Saskatchewan.[76]

May

- J. D. Stewart, accompanied by Everhart, discovered a nearly complete Dolichorhynchops rear flipper in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk. Unfortunately it was too late to correct the erroneous statements in his aforementioned paper regarding the supposed rarity of plesiosaurs in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk. The flipper is now catalogued as LACMNH 148920.[77]

October

- Stewart's paper, complete with his now-erroneous statements, was published in the Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook in honor of the society's 50th anniversary meeting in Lawrence that year.[75]

- Ralph E. Molnar published suspicion that the "Kronosaurus queenslandicus" specimen discovered by the Harvard expedition might be a distinct species.[47]

- Several Elasmosaurus vertebrae and gastroliths were found near the site where the type specimen of the genus itself was excavated.[64]

- Cruikshank and others hypothesized that plesiosaurs could smell and taste water that "passively" flowed through their nasal passages while they swam.[53]

- Hampe described the new species Kronosaurus boyacensis.[19]

- Everhart discovered some fragmentary plesiosaur fossils in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk of Kansas. Some of the fossils seemed to have been partially digested. The remains were later catalogued as FHSM VP-13966.[75]

- Everhart showed the partially digested fossils to J. D. Stewart, who recognized them as pieces of a plesiosaur skull. The fossils are now catalogued as [clarification needed][77]

- Everhart and his wife helped excavated a Styxosaurus snowii specimen in Kansas. During the dig Mrs. Everhart discovered an additional partial plesiosaur skeleton.[78]

- Robert T. Bakker nicknamed the long-necked plesiosaurs "swan lizards".[72]

- Robert T. Bakker argued that plesiosaurs suffered several major mass extinction.[79]

- Robert T. Bakker argued that ichthyosaurs became extinct. Further, they convergently evolved many traits similar to those of ichthyosaurs, such as long snouts and large eyes.[80]

- Tony Thulborn and Susan Turner examined the crushed skull of the long-necked plesiosaur Woolungasaurus and found the presence of tooth marks left by some giant predator. They hypothesized that a Kronosaurus was the culprit.[81]

- Storrs, like Williston and Shuler before him, argued that long-necked plesiosaurs had relatively inflexible necks.[36]

- Rothschild and Martin reported the presence of the remains of a fossilized fetus preserved in the abdomen of a Dolichorhynchops osborni.[82]

- Glenn W. Storrs formally described the world's smallest plesiosaur for the scientific literature.[74]

- vandalized before discovery by scientists. A large hole was found near the baby pliosaur that could have once held the bones of its mother or other pod members.[84]

- An amateur fossil hunter named Simon Carpenter discovered a 7-foot-long Pliosaurus brachyspondylus skull in claypits of the Blue Circle cement works near Westbury, England. More of the skeleton was found in the vicinity and this specimen came to be regarded as the best preserved pliosaur ever found;[85] it is held by Bristol Museum.[86]

- A man named Alan Dawn discovered a previously unknown kind of pliosaur in the Simolestes keileni.[19]

- Ken Carpenter recognized the plesiosaur specimen discovered by Pamela Everhart in 1992 as one of the largest known specimens of Dolichorhynchops osborni, now catalogued as CMC VP-7055.[78]

- Carpenter published a review of the Cretaceous short-necked plesiosaurs known from western North America. In this paper he both revised these plesiosaurs' taxonomy as well as offering observations on their biostratigraphy and evolution.[88] Carpenter described the new genus and species Plesiopleurodon wellesi.[21] He also argued against the prevailing trend to treat Dolichorhynchops Trinacromerum as taxonomic synonyms by observing that they could be distinguished based on their skull anatomy.[89] However, he did conclude that the Trinacromerum species T. anonymum and T. willistoni were junior synonyms of T. bentonianum.[31]

In his remarks on short-necked plesiosaur evolution, Carpenter argued that polycotylids were more closely related to long-necked plesiosaurs than pliosaurs.[90] He observed that Trinacromerum bentonianum seems to have existed from the late Cenomanian to the Turonian. This represents a span of time approximating 3.3 million years. He found Dolichorhynchops osborni to have had an even longer lifespan, from the middle Turonian to the early Campanian., or roughly 4 million years. His research also suggested that there was a span of time during the life of the Western Interior Seaway in which it was not inhabited by polycotylids.[29]

He also reported that the Dolichorhynchops specimen KUVP 40001 from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota may have achieved the extraordinary length of 23 feet.[34] The large size of the Pierre Shale Dolichorhynchops compared to those of the earlier Smoky Hill Chalk suggested to Carpenter that these plesiosaurs were evolving larger body sizes over time. In fact the Pierre Shale specimens of Dolichorhynchops were nearly as large as Brachauchenius lucasi.[78] Carpenter described a particularly large specimen of that latter taxon in this paper as well, specifically FHSM VP-321.[52] His study of Brachauchenius led him to concur with Williston that it was closely related to Liopleurodon ferox.[52]

- Pachycostasaurus dawni. The researchers noticed that its bones were very dense. So dense, they speculated it would naturally sink in the water and spent most of its time feeding on soft bodied animals living near the seafloor.[87]

- Cruickshank and Long described the new species Leptocleidus clemai.[19]

- Gasparini described the new species Maresaurus coccai.[21]

- Liggett and others reported the discovery of a giant plesiosaur flipper from the Greenhorn Limestone of Kansas. Although a significant portion of the specimen was missing, it implied a life length of more than 2 m. The researchers tentatively attributed the flipper to Brachauchenius lucasi. The specimen is now catalogued as FHSM VP-13997.[78]

- Two fossilized skeletons of Dolichorhynchops herschelensis are discovered near Herschel, Saskatchewan at the Ancient Echoes Interpretive Centre- only the second and third specimens to have ever been found.[91]

- ammonites.[92]

- John A. Long bemoaned the fact that the putative "Kronosaurus queenslandicus" uncovered by a Harvard team during the early 1930s had still not been formally described for the scientific literature.[47]

- Michael Everhart and Glenn Storrs excavated additional Elasmosaurus ribs, vertebrae and gastroliths at the site of the 1991 discovery.[64]

- Long reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in Australia.[34]

- Carpenter published a summary of the elasmosaur fossils discovered in the Smoky Hill Chalk.[42]

- Storrs published a revision of Elasmosaurus taxonomy.[93] He reinterpreted the Elasmosaurus nobilis type specimen as indeterminate elasmosaurid remains.[32] He also reinterpreted the "Elasmosaurus" sternbergi type specimen as two cervical and one dorsal vertebrae rather than two dorsal vertebrae as Williston had reported in his original description. However, Storrs did agree that it was an elasmosaur specimen rather than a pliosaur as argued by Welles in 1952.[43]

21st century

2000s

- Theagarten Lingham-Soliar published further criticism of Robinson's interpretation of the biomechanics of plesiosaur locomotion.[94]

- O'Keefe described the new species Hauffiosaurus zanoni.[21]

- Michael Everhart re-examined UNSM 1195.[56]

- Lingham-Soliar argued that plesiosaur hind-flippers weren't mobile or muscular enough to help propel them through the water.[95]

- Everhart published a study of the gastroliths associated with the elasmosaur specimen KUVP 129744 from Kansas. The specimen was associated with roughly 13.1 kg of gastroliths. The largest of these was 17 cm long and 1.4 kg in weight. Everhart would later compare its size to that of a softball and observe that not only was it one of the largest known plesiosaur gastroliths, but also one of the largest gastroliths from any animal.[37]

November

- The Advertiser, a newspaper based in Adelaide, Australia bought the Addyman opalized plesiosaur specimen for $25,000 and donated it to the South Australian Museum. A paleontologist at the museum named Ben Kear identified it as a member of the genus Leptocleidus. The two foot long specimen was the smallest specimen of the genus ever found and probably a baby.[66]

- David J. Cicimiurri and Michael J. Everhart published a study of the Styxosaurus snowii specimen NJSM 15435, which preserved both stomach contents and gastroliths.[37] Among the stomach contents were remains of the bony fish Enchodus.[53] By this point in time at least fifteen different plesiosaur specimens were known with preserved stomach contents.[96] The researchers observed that the Enchodus remains preserved in NJSM 15435 were an example of shifting dietary preferences in plesiosaurs, who fed primarily on cephalopods for most of their evolutionary history, before coming to rely more heavily on fishes during the Late Cretaceous.[53]

They also noted that some of NJSM 15435's gastroliths were scarred by rounded chips and arc-shaped marks. These were likely inflicted by contact with other gastroliths during the churning of the animal's stomach, and constituted physical evidence that plesiosaurs used their gastroliths to help break down their food during digestion.[97] Cicimurri and Everhart disputed the hypothesis that plesiosaurs used their gastroliths for ballast on the grounds that swallowing and vomiting such stones would be relatively difficult for the long-necked forms and their feeding grounds may have been hundreds of miles from sources of stones.[98]

- Everhart resumed the study of the partially digested plesiosaur skull bones, FHSM VP-13966. He sought the expertise of Ken Carpenter due to his relevant 1996 paper on short-necked plesiosaurs. Carpenter identified the bones as probable Dolichorhynchops remains.[31]

- Noe published another study of Pachycostasaurus. He changed his mind regarding its diet. Where previously he believed it to feed on soft-bodied animals, the robust and "heavily ornamented" build of its teeth suggested it fed on harder, bonier prey.[87]

September

- Eberhard Frey, Celine Bachy, and Wolfgang Stinnesbeck gave a presentation on the Aramberri pliosaur remains to the European Workshop on Vertebrate Paleontology in Florence, Italy. The paleontologists could not identify its species.[99]

September 11

- Everhart was forced to cancel plans to examined the Tylosaurus specimen USNM 8898 and its polycotylid dinner USNM 9468 due to the September 11th terrorist attacks.[55]

November

- Everhart was finally able to examine the tylosaur specimen with the polycotylid stomach contents.[55]

2001–2002

- Cruickshank and Fordyce described the new species Kaiwhekea katiki.[21]

- Druckenmiller described the new species Edgarosaurus muddi.[21]

- Michael Everhart examined FHSM VP-398 and found Sternberg's original note revealing that these fossils had been collected at the same site as the 1991 Elasmosaurus discovery. Everhart realized that the remains discovered there collectively represented most of the bones that had been missing from the Elasmosaurus type specimen. He inferred that they may represent fragments that fell off of the decomposing type carcass while it was adrift, before its final burial and fossilization.[64]

- An elasmosaur specimen with over 600 associated gastroliths was discovered in the Pierre Shale of Nebraska. The specimen is now catalogued as UNSM 1111–002.[37]

December 30

- The

- The Santee Sioux land.[102] The Santee people requested that the skeleton be mounted and displayed with a plaque acknowledging them as the source of the fossils and as having given permission for the museum to display the remains. However, the museum claims it could not honor the request as it did not have the funding to mount the skeleton for display, and it further claimed that the land the fossils were recovered from was of "disputed" ownership.[103]

- Mulder and others reported the presence of elasmosaur remains in Europe.[34]

- Sato described the new genus and species Terminonatator ponteixensis. In his study of the animal's skeleton, he found that the vertebral discs in the neck were flat on both sides and packed tightly together. He estimated that there would have been only about 0.5 cm of cartilaginous padding between these discs. These observations provided additional evidence for a lack of flexibility in plesiosaur necks.[36]

- Everhart argued contrary to Carpenter's 1996 paper that polycotylids were present throughout the life of the Western Interior Seaway.[48]

- Everhart finally described the partially digested partial plesiosaur skull he discovered in 1992. These were among the earliest known plesiosaur fossils in the Smoky Hill Chalk. He has since concluded that the animal that partially digested the remains was probably a shark, which would go on to vomit them up before they were buried and preserved.[77]

- Bardet and others described the new species Thililua longicollis.[21]

- Michael Everhart found Charles H. Sternberg's account of the discovery of the Elasmosaurus sternbergi type specimen in his 1932 book. This allowed Everhart to verify the specimen's geographic and stratigraphic provenance.[104]

- Everhart argued that the greater abundance of arc shaped marks and rounded divots in plesiosaur gastroliths compared to rocks deposited by ancient rivers and sea shores was evidence for their use in the breakdown of plesiosaurs' food.[97]

- Everhart redescribed the Tylosaurus specimen USNM 8898 and its polycotylid dinner USNM 9468. Contrary to Sternberg's original assessment of the stomach contents as representing a "huge plesiosaur" Everhart found it to be a young polycotylid only about 2-2.5 m long.[55]

- Noe et al. described the new species Pliosaurus portentificus.[19]

- Sato described the new species Dolichorhynchops herschelensis.[19]

- Sachs described the species now known as Eromangasaurus australis.[21]

- Buchy et al. described the new species Manemergus anguirostris.[21]

- The plesiosaur remains found at Dolichorhynchops herschelensis, by Dr. Tamaki Sato, a Japanese vertebrate paleontologist.[105]

- Buchy described the new species Libonectes atlasense.[19]

- Kear described the new species Umoonasaurus demoscyllus.[21]

- Kear described the new species Opallionectes andamookaensis.[21]

- Sato et al. described the new species Futabasaurus suzukii.[21]

- Albright et al. described the new species Eopolycotylus rankini.[21]

- Albright et al. described the new species Palmula quadratus.[21]

2010s

- Sennikov and Arkhangelsky described the new genus and species Alexeyisaurus karnoushenkoi.[106]

- Smith and Vincent described the new genus Meyerasaurus.[107]

- K-selected reproductive strategy.[10]

- Berezin described the new genus and species Abyssosaurus nataliae[108]

- Benson and others described the new species Hauffiosaurus tomistomimus[109]

- Ketchum and Benson described the new genus and species Marmornectes candrewi[110]

- Schwermann and Sander described the new genus and species Westphaliasaurus simonsensii [111]

- Vincent and others described the new genus and species Zarafasaura oceanis[112]

- Kubo, Mitchell and Henderson described the new genus and species Albertonectes vanderveldei.[113]

- Vincent and Benson described the new genus and species Anningasaura lymense.[114]

- Benson, Evans and Druckenmiller described the new genera and species Stratesaurus taylori.[115]

- Knutsen, Druckenmiller and Hurum described the new genus and species Djupedalia engeri.[116]

- McKean described the new species Dolichorhynchops tropicensis.[117]

- Smith, Araújo and Mateus described the new genus and species Lusonectes sauvagei.[118]

- Knutsen, Druckenmiller and Hurum described the new species Pliosaurus funkei[119]

- Knutsen, Druckenmiller and Hurum described the new genus Spitrasaurus and two species, S. wensaasi, and S. larseni.[120]

- Benson and others described the new genus Vectocleidus pastorum.[121]

- Vincent, Bardet and Mattioli described the new genus and species Cryonectes neustriacus[122]

- Hampe described the new genus and species Gronausaurus wegneri[123]

- Schumacher, Carpenter and Everhart described the new genus and species Megacephalosaurus eulerti[124]

- Benson and others described the new Pliosaurus species P. carpenteri, P. kevani, and P. westburyensis.[125]

- Otero and others described the new species Aristonectes quiriquinensis.[126]

- Gasparini and O’Gorman described the new species Pliosaurus patagonicus.[127]

- Cau and Fanti described the new genus and species Anguanax zignoi.[128]

- Smith described the new genus Atychodracon.[129]

- Araújo and others described the new genus and species Cardiocorax mukulu.[130]

- O’Gorman and others described the new genus and species Vegasaurus molyi.[131]

- A study on the teeth replacement patterns during the ontogeny in pliosaurids is published by Sassoon, Foffa & Marek (2015).[132]

- Otero and others described the new genus and species Alexandronectes zealandiensis.

- O’Gorman described the new genus Kawanectes.

- Páramo and others described the new genus and species Stenorhynchosaurus munozi.[133]

- Cheng and others described the new genus Dawazisaurus.

- Klein and others described the new species Lariosaurus vosseveldensis.

- Efimov, Meleshin and Nikiforov described the new species Polycotylus sopozkoi.

- A reassessment of fossils attributed to the genus Polyptychodon is published by Madzia (2016), who considers the type species of this genus, P. interruptus, to be nomen dubium, and the genus Polyptychodon to be a wastebasket taxon.[134]

- O'Gorman (2016) provides a new diagnosis for plesiosaur material from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Moreno Formation (California, USA), which he interprets as representing the first aristonectine plesiosaur reported from the Northern Hemisphere.[135]

- A redescription of the Gronausaurus wegneri to be a junior synonym of B. brancai.[136]

- Gómez-Pérez and Noè described the new genus and species Acostasaurus pavachoquensis.

- Sachs, Hornung, and Kear described the new genus and species Lagenanectes richterae.

- Fischer and others described the new genus and species Luskhan itilensis.

- Frey and others described the new genus and species Mauriciosaurus fernandezi.

- Serratos, Druckenmiller, and Benson described the new genus and species Nakonanectes bradti.

- Wintrich and others described the new genus and species Rhaeticosaurus mertensi.

- Smith and Araújo described the new genus and species Thaumatodracon wiedenrothi.

- A study on the mechanisms generating vertebral counts and their regionalisation during embryo development that were responsible for high plasticity of the body plan of sauropterygians is published by Soul & Benson (2017).[137]

- A study on the function of the long neck in plesiosaurs as indicated by the anatomy of the neck is published by Noè, Taylor & Gómez-Pérez (2017).[138]

- A study on the large, paired openings in the neck vertebrae of plesiosaurs and their implications for inferring the anatomy of the vascular system in the neck of plesiosaurs is published by Wintrich, Scaal & Sander (2017).[139]

- A study on the swimming method of plesiosaurs is published by Muscutt et al. (2017).[140]

- An assessment of the completeness of the plesiosaur fossil record is published by Tutin & Butler (2017).[141]

- A description of a new specimen of Colymbosaurus svalbardensis from the Tithonian–Berriasian Agardhfjellet Formation (Svalbard, Norway), a reevaluation of the diagnostic features of the species and a study on its phylogenetic relationships is published by Roberts et al. (2017).[142]

- A study on the tooth formation cycle in elasmosaurid plesiosaurs is published by Kear et al. (2017).[143]

- A redescription of the holotype specimen of Tuarangisaurus keyesi and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of the species is published by O'Gorman et al. (2017).[144]

- A study on the anatomy of the vertebra of Vegasaurus molyi and its implications for the anatomy of the nervous system of the species is published by O'Gorman & Fernandez (2017).[145]

- A study on the skeletal plesiosaur specimen recovered from the Lopez de Bertodano Formation (Seymour Island, Antarctica) is published by O'Gorman, Talevi & Fernández (2017).[146]

- A redescription of the anatomy of the holotype skull of Morturneria seymourensis is published by O'Keefe et al. (2017).[147]

- A reappraisal and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of Mauisaurus is published by Hiller et al. (2017).[148]

- Libonectes atlasense is redescribed by Sachs & Kear (2017), who consider this species to be likely synonymous with Libonectes morgani.[149]

- An elasmosaurid specimen closely related to Weddellonectia.[150]

- Sachs and Kear described the new genus and species Arminisaurus schuberti.

- O’Gorman, Gasparini and Spalletti described the new species Pliosaurus almanzaensis.

- Páramo-Fonseca, Benavides-Cabra and Gutiérrez described the new genus and species Sachicasaurus vitae.[151]

- De Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez‐García described the new genus and species Paludidraco multidentatus.[152]

- A study aiming to estimate metabolic rates and bone growth rates in plesiosaurs, is published by Fleischle, Wintrich & Sander (2018).[153]

- A study on the variability of the skull morphology in Simosaurus gaillardoti is published by de Miguel Chaves, Ortega & Pérez-García (2018).[154]

- An incomplete

- The first Upper Jurassic Ameghino (= Nordensköld) Formation (Antarctic Peninsula) by O’Gorman et al. (2018).[156]

- Lower Cretaceous (Berriasian and Valanginian) of the Volga region (European Russia) by Zverkov et al. (2018), who argue that their findings challenge the hypothesis that only one lineage of pliosaurids crossed the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary.[157]

- Complete mandible of Kronosaurus queenslandicus is described from the Albian Allaru Mudstone (Australia) by Holland (2018).[158]

- Description of the skull bones of Abyssosaurus nataliae from the Cretaceous (Hauterivian) of Chuvashia (Russia) is published by Berezin (2018), who also revises the species diagnosis.[159]

- A study on a specimen of Cryptoclidus eurymerus from the Middle Jurassic (Callovian) of Peterborough (United Kingdom), with the left forelimb injured by a predator causing the loss of use of this limb but which nevertheless survived for some time after that injury, is published by Rothschild, Clark & Clark (2018), who also evaluate the implications of this specimen for the various hypotheses on plesiosaur propulsion.[160]

- A study on the range of motion of the neck of an exceptionally preserved specimen of Nichollssaura borealis is published by Nagesan, Henderson & Anderson (2018).[161]

- A study on the morphology of Occultonectia.[162]

- Two new plesiosaur specimens, including a specimen of the species

- Description of a skull and partial postcranial skeleton of a juvenile Upper Cretaceous Tahora Formation (New Zealand), referred to the species Tuarangisaurus keyesi, is published by Otero et al. (2018).[164]

- An exceptionally well-preserved elasmosaurid basicranium, providing new information on the anatomy of the skull of elasmosaurids, is described from the Upper Cretaceous (lower Campanian) Rybushka Formation (Russia) by Zverkov, Averianov & Popov (2018).[165]

- Redescription of Aristonectes quiriquinensis, providing new information on the anatomy of this species, is published by Otero, Soto-Acuña & O'keefe (2018).[166]

- Cranial material of a non-aristonectine elasmosaurid plesiosaur is described from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Cape Lamb Member of the Snow Hill Island Formation (Vega Island, Antarctica) by O'Gorman et al. (2018).[167]

- New elasmosaurid specimen is described from the upper Maatrichtian horizons of the weddellonectian elasmosaurid specimens from Antarctica reported so far, documenting the presence of at least two different non-aristonectine elasmosaurids in Antarctica during the late Maastrichtian, and confirming the coexistence of aristonectine and non-aristonectine elasmosaurids in Antarctica until the end of the Cretaceous.[168]

- Redescription of the holotype of Styxosaurus snowii and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of this species is published by Sachs, Lindgren & Kear (2018).[169]

- Pathological fusions of neck vertebrae are reported in four plesiosaur specimens from different geological horizons by Sassoon (2019).[170]

- A study on the morphology of the teeth and skull of Megacephalosaurus eulerti, and on their implications for assessing the phylogenetic relationships of this species, will be published by Madzia, Sachs & Lindgren (2019).[171]

- New plesiosaur fossils are described from the Barremian levels of the Arcillas de Morella Formation (Spain) by Quesada et al. (2019), including the first leptocleidid fossil reported from the Iberian Peninsula.[172]

- A study on the skull morphology of two specimens of Dolichorhynchops bonneri from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota, as well as on the phylogenetic relationships of this species, is published by Morgan & O'Keefe (2019).[173]

- A study on bone Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, and on its implications for interpreting a histological growth series in Dolichorhynchops bonneri, is published by O’Keefe et al. (2019).[174]

- Skull and neck bones of an elasmosaurid plesiosaur are described from the Cenomanian Hegushi Formation (Japan) by Utsunomiya (2019), representing the oldest confirmed elasmosaurid in Japan and in East Asia.[175]

- Páramo Fonseca and others described the new genus and species Leivanectes bernardoi.[176]

- Vincent and Storrs described the new genus and species Lindwurmia thiuda.[177]

- Vincent and others described the new species Microcleidus melusinae.[178]

2020s

- Roberts and others described the new genus and species Ophthalmothule cryostea.[179]

- Sachs and others referred Simolestes keileni to a new genus Lorrainosaurus.[180]

- Clark and others describe the new genus and species Unktaheela specta and move the species "Dolichorhynchops" bonneri to the new genus Martinectes and "Dolichorhynchops" tropicensis to the new genus Scalamagnus.[181]

- Sachs, Eggmaier and Madzia described a new species and genus of plesiosauroid plesiosaur, Franconiasaurus brevispinus, from the Toarcian deposits of Germany.[182]

See also

- Timeline of paleontology

- Timeline of ichthyosaur research

- Timeline of mosasaur research

- List of plesiosaurs

Footnotes

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "Introduction: Isn't That the Loch Ness Monster?", page 3.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Marine Reptiles: An Overview", page 20.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Marine Reptiles: An Overview", page 21.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 118.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 119.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 136.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 137.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 138.

- ^ a b c Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 139.

- ^ a b O'Keefe and Chiappe (2011); "Abstract", page 870.

- ^ For the mythical creatures as Thunder Birds and Water Monsters, see Mayor (2005); "The Stone Medicine Bone, Pawnee Territory", page 178. For plesiosaurs as a specific source of these legends, see "Cheyenne Fossil Knowledge", page 211.

- ^ Stukeley (1719); in passim.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 123.

- ^ Storrs (1997); "Remarks:", pages 150-151.

- ^ a b c Storrs (1997); "Introduction", page 146.

- ^ a b Storrs (1997); "Remarks:", page 151.

- ^ For the original publication, see Conybeare (1824).

- ^ a b Storrs (1997); "Referred specimens:", page 150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be Smith (2007); "Appendix 1", page 257.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Marine Reptiles: An Overview", page 37.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Smith (2007); "Appendix 1", page 258.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 166.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Marine Reptiles: An Overview", pages 21-22.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 121.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", pages 121–122.

- ^ a b c d Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 122.

- ^ a b c Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", pages 146–147.

- ^ a b Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 123.

- ^ a b c Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 147.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", pages 130-132.

- ^ a b c d e f g Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 150.

- ^ a b c d Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 128.

- ^ a b Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", pages 128-129.

- ^ a b c d e f g Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 129.

- ^ Storrs (1997); "Forelimb", page 171.

- ^ a b c d e Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 132.

- ^ a b c d e f Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 137.

- ^ Storrs (1997); "Discussion", page 180.

- ^ a b Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", pages 151–152.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 149.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", pages 188–189.

- ^ a b Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 125.

- ^ a b c d Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 126.

- ^ a b c d Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 154.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 138.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 153.

- ^ a b c d e Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 176.

- ^ a b c Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 148.

- ^ a b c Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 156.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", pages 156–157.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 184.

- ^ a b c d e Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 152.

- ^ a b c d e Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 134.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", pages 144–145.

- ^ a b c d e Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 145.

- ^ a b c Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 127.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 175.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 121.

- ^ a b c d Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 181.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 161.

- ^ Storrs (1997); "Discussion", page 179.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 188.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", pages 175–176.

- ^ a b c d Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 124.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 154.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 174.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", pages 150–151.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 151.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", pages 139–140.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 142.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", pages 153–154.

- ^ a b Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 152.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 143.

- ^ a b c Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 150.

- ^ a b c Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", pages 149–150.

- ^ "Exploring in Herschel, Saskatchewan « Royal Saskatchewan Museum". royalsaskmuseum.ca. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ a b c Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 149.

- ^ a b c d Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 153.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 163.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", pages 189–191.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 176. For the original paper, see Thulborn and Turner (1993).

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", pages 139–140.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", pages 150–151.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 151.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 169.

- ^ "Doris the Pliosaurus". Bristol Museums. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ a b c Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 191.

- ^ Carpenter (1996); in passim.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 189.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 144.

- ^ "History Of Ancient Echoes". www.ancientechoes.ca. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", pages 155–156.

- ^ Storrs (1999); in passim.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 141.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 135.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 155.

- ^ a b Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 139.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", page 159.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", pages 181–182.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Plesiosaurs", pages 142–143.

- ^ Ellis (2003); "The Pliosaurs", page 182.

- ^ Mayor (2005); "Cultural and Historical Conflicts", page 303.

- ^ Mayor (2005); "Cultural and Historical Conflicts", pages 303–304.

- ^ Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed", page 126–127.

- S2CID 131128997.

- ^ Sennikov and Arkhangelsky (2010); in passim.

- ^ Smith and Vincent (2010); in passim.

- ^ Berezin (2011); in passim.

- ^ Benson and others (2011); in passim.

- ^ Ketchum and Benson (2011); in passim.

- ^ Schwermann and Sander (2011); in passim.

- ^ Vincent et al. (2011); in passim.

- ^ Kubo, Mitchell and Henderson (2012); in passim.

- ^ Vincent and Benson (2012); in passim.

- ^ Benson, Evans and Druckenmiller (2012); in passim.

- ^ Knutsen, Druckenmiller and Hurum (2012b); in passim.

- ^ McKean (2012); in passim.

- ^ Smith, Araújo and Mateus (2012); in passim.

- ^ Knutsen, Druckenmiller and Hurum (2012a); in passim.

- ^ Knutsen, Druckenmiller and Hurum (2012c); in passim.

- ^ Benson et al. (2013b); in passim.

- ^ Vincent, Bardet, and Mattioli (2013); in passim.

- ^ Hampe (2013); in passim.

- ^ Schumacher, Carpenter and Everhart (2013); in passim.

- ^ Benson et al. (2013a); in passim.

- ^ Otero et al. (2014); in passim.

- ^ Gasparini and O’Gorman (2014); in passim.

- ^ Cau and Fanti (2015); in passim.

- ^ Smith (2015); in passim.

- ^ Araujo et al. (2015); in passim.

- ^ O’Gorman et al. (2015); in passim.

- PMID 26715998.

- ^ Páramo et al. (2016); in passim.

- PMID 27190712.

- .

- PMID 28028478.

- PMID 28240769.

- S2CID 44182876.

- .

- PMID 28855360.

- PMID 29497243.

- S2CID 26328874.

- PMID 28241059.

- .

- .

- S2CID 133071929.

- S2CID 91144814.

- S2CID 132037930.

- .

- S2CID 132473041.

- S2CID 135054193.

- PMID 30068541.

- PMID 29892509.

- S2CID 102345796.

- S2CID 134114013.

- .

- S2CID 134889277.

- S2CID 91599158.

- S2CID 91151554.

- doi:10.26879/719.

- PMID 30224996.

- PMID 29657811.

- .

- .

- S2CID 132125319.

- S2CID 90977078.

- S2CID 134284389.

- S2CID 134265841.

- S2CID 134569623.

- S2CID 135461586.

- S2CID 133859507.

- S2CID 134139253.

- S2CID 134887820.

- PMID 33791514.

- .

- S2CID 134171636.

- S2CID 59304744.

- S2CID 135111068.

- PMID 32266112.

- PMC 10579310.

- ISSN 0195-6671.

- .

References

A-F

- Andrews, C. (1896). "On the structure of the plesiosaurian skull". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 52 (1–4): 246–253. S2CID 128737288.

- Andrews, C. (1910). A descriptive catalogue of the marine reptiles of the Oxford Clay. Part I. London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 205.

- R. Araújo; M.J. Polcyn; A.S. Schulp; O. Mateus; L.L. Jacobs; A. Olímpio Gonçalves & M.-L. Morais (2015). "A new elasmosaurid from the early Maastrichtian of Angola and the implications of girdle morphology on swimming style in plesiosaurs". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 109–120. S2CID 86616531.

- Roger B. J. Benson; Mark Evans & Patrick S. Druckenmiller (2012). "High Diversity, Low Disparity and Small Body Size in Plesiosaurs (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31838. PMID 22438869.

- Roger B. J. Benson; Mark Evans; Adam S. Smith; Judyth Sassoon; Scott Moore-Faye; Hilary F. Ketchum & Richard Forrest (2013). "A Giant Pliosaurid Skull from the Late Jurassic of England". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e65989. PMID 23741520.

- Roger B. J. Benson; Hilary F. Ketchum; Darren Naish & Langan E. Turner (2013). "A new leptocleidid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Vectis Formation (Early Barremian–early Aptian; Early Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight and the evolution of Leptocleididae, a controversial clade". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (2): 233–250. S2CID 18562271.

- Roger B. J. Benson; Hilary F. Ketchum; Leslie F. Noè & Marcela Gómez-Pérez (2011). "New information on Hauffiosaurus (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) based on a new species from the Alum Shale Member (Lower Toarcian: Lower Jurassic) of Yorkshire, UK" (PDF). Palaeontology. 54 (3): 547–571. S2CID 55436528.

- A. Yu. Berezin (2011). "A new plesiosaur of the family Aristonectidae from the early cretaceous of the center of the Russian platform". Paleontological Journal. 45 (6): 648–660. S2CID 129045087.

- Brown, B. (1913). "A new plesiosaur, Leurospondylus, from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 32: 606–615.

- Buckland, W. (1837). Geology and Mineralogy, Considered With Reference to Natural Theology. London: William Pickering. p. 605.

- Carpenter, K. (1996). "A review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the Western Interior, North America" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 210 (2): 259–287. .

- Andrea Cau & Federico Fanti (2015). "High evolutionary rates and the origin of the Rosso Ammonitico Veronese Formation (Middle-Upper Jurassic of Italy) reptiles". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 28 (7): 1–11. S2CID 86528030.

- Conybeare, W. D. (1824). "On the discovery of an almost perfect skeleton of the Plesiosaurus". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 2: 382–389.

- Cruickshank, A. R. I.; Small, P. G.; Taylor, M. A. (1991). "Dorsal nostrils and hydrodynamically driven underwater olfaction in plesiosaurs". Nature. 352 (6330): 62–64. S2CID 4353612.

- Dames, W. (1895). "Die Plesiosaurier der s'u'ddeutschen Liasformation". Abhandlungen der Königlichen Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: 1–83.

- De la Beche, H. T.; Conybeare, W. D. (1821). "Notice of the discovery of a new fossil animal, forming a link between the Ichthyosaurus and the crocodile, together with general remarks on the osteology of Ichthyosaurus". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 5: 559–594.

- Ellis, Richard (2003). Sea Dragons - Predators of the Prehistoric Oceans. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1269-7.

- Everhart, Michael J. (2005). Oceans Of Kansas: A Natural History Of The Western Interior Sea. Life of the Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 322.

G-L

- Zulma Gasparini & José P. O'Gorman (2014). "A new species of Pliosaurus (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Upper Jurassic of northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 51 (4): 269–283. S2CID 130194647.

- Oliver Hampe (2013). "The forgotten remains of a leptocleidid plesiosaur (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauroidea) from the Early Cretaceous of Gronau (Münsterland, Westphalia, Germany)". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 87 (4): 473–491. S2CID 129834688.

- Huene, F. R. F. von (1923). "Ein neuer Plesiosaurier aus dem oberen Lias W'u'rttembergs". Jareshefte das Vereins F'u'r Vaterlandische Naturkunde in W'u'rttemberg. 79: 1–21.

- Hulke, J. W. (1883). "The anniversary address of the president". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 39 (1–4): 38–65. S2CID 219238884.

- Hilary F. Ketchum & Roger B. J. Benson (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129.

- Espen M. Knutsen; Patrick S. Druckenmiller & Jørn H. Hurum (2012). "A new species of Pliosaurus (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Middle Volgian of central Spitsbergen, Norway". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92 (2–3): 235–258.

- Espen M. Knutsen; Patrick S. Druckenmiller & Jørn H. Hurum (2012). "A new plesiosauroid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Agardhfjellet Formation (Middle Volgian) of central Spitsbergen, Norway". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92 (2–3): 213–234.

- Espen M. Knutsen; Patrick S. Druckenmiller & Jørn H. Hurum (2012). "Two new species of long-necked plesiosaurians (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Upper Jurassic (Middle Volgian) Agardhfjellet Formation of central Spitsbergen". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92 (2–3): 187–212.

- Tai Kubo; Mark T. Mitchell & Donald M. Henderson (2012). "Albertonectes vanderveldei, a new elasmosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 557–572. S2CID 129500470.

- Lydekker, R. (1889). Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural History). Part II. Containing the orders Ichthyopterygia and Sauropterygia. London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 307.

- Lydekker, R. (1890). Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural History). Part IV. The orders Anomodontia, Ecaudata, Caudata, and Labyrinthodontia; and supplement. London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 295.

M-R

- Mansel-Pleydell, J. C. (1888). "Fossil reptiles of Dorset". Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club. 9: 1–40.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2005). Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11345-6.

- Rebecca Schmeisser McKean (2012). "A new species of polycotylid plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Turonian of Utah: extending the stratigraphic range of Dolichorhynchops". Cretaceous Research. 34: 184–199. .

- José P. O’Gorman; Leonardo Salgado; Eduardo B. Olivero & Sergio A. Marenssi (2015). "Vegasaurus molyi, gen. et sp. nov. (Plesiosauria, Elasmosauridae), from the Cape Lamb Member (lower Maastrichtian) of the Snow Hill Island Formation, Vega Island, Antarctica, and remarks on Wedellian Elasmosauridae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (3): e931285. S2CID 128965534.

- O'Keefe, F.R.; Chiappe, L.M. (2011). "Viviparity and K-selected life history in a Mesozoic marine plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia)". Science. 333 (6044): 870–873. S2CID 36165835.

- Osborn, H. F. (1903). "The reptilian subclasses Diapsida and Synapsida and the early history of the Diaptosauria". Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History. 1: 449–507.

- Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; Frank Robin O'Keefe; José P. O’Gorman; Wolfgang Stinnesbeck; Mario E. Suárez; David Rubilar-Rogers; Christian Salazar & Luis Arturo Quinzio-Sinn (2014). "Aristonectes quiriquinensis, sp. nov., a new highly derived elasmosaurid from the upper Maastrichtian of central Chile". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (1): 100–125. S2CID 84729992.

- Owen, R. (1840a). "Report on British fossil reptiles. Part I.". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1839: 43–126.

- Owen, R. (1840b). "A description of a specimen of the Plesiosaurus macrocephalus, Conybeare, in the collection of Viscount Cole, MP, DCL, FGS, &c". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 5: 559–594.

- Owen, R. (1860). "On the orders of fossil and Recent Reptilia, and their distribution in time". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 29: 153–166.

- Owen, R. (1865). A monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Liassic formations. Part I, Sauropterygia. Palaeontographical Society Monograph. Vol. 17. pp. 1–40.

- Páramo, María E.; Gómez-Pérez, Marcela; Noé, Leslie F.; Etayo, Fernando (2016-04-06). "Stenorhynchosaurus munozi, gen. et sp. nov. a new pliosaurid from the Upper Barremian (Lower Cretaceous) of Villa de Leiva, Colombia, South America". Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales. 40 (154): 84–103. ISSN 2382-4980.

- Parkinson, J. (1822). Outline of Oryctology: An Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains; Especially of Those Found in British Strata. London. p. 350.

S-Z

- Sauvage, H.-E. (1882). "Recherches sur les reptiles trouvé dans le Gault de l'est du Bassin de Paris". Mémoires de la Société Géologique de France. 2: 24–28.

- Sauvage, H.-E. (1898). "Les reptiles et les poissons des terrains Mésozoîques du Portugal". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 26: 442–446.

- Schumacher, B. A.; Carpenter, K.; Everhart, M. J. (2013). "A new Cretaceous Pliosaurid (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Carlile Shale (middle Turonian) of Russell County, Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (3): 613. S2CID 130165209.

- Sciau, J.; Crochet, J.-Y.; Mattei, J. (1990). "Le premier squelette de plesiosaure de France sur le Causse du Larzac (Toarcien, Jurassique Infe'rieur)". Geobios. 23 (1): 111–116. .

- Seeley, H. G. (1865). "On two new plesiosaurs from the Lias". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 16 (95): 352–359. .

- Seeley, H. G. (1874). "Note on the generic modifications of the plesiosaurian pectoral arch". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 30 (1–4): 436–449. S2CID 128746688.

- A. G. Sennikov; M. S. Arkhangelsky (2010). "On a Typical Jurassic Sauropterygian from the Upper Triassic of Wilczek Land (Franz Josef Land, Arctic Russia)". Paleontological Journal. 44 (5): 567–572. S2CID 88505507.

- Leonie Schwermann & Martin Sander (2011). Osteologie und Phylogenie von Westphaliasaurus simonsensii: Ein neuer Plesiosauride (Sauropterygia) aus dem Unteren Jura (Pliensbachium) von Sommersell (Kreis Höxter), Nordrhein-Westfalen, Deutschland [=Osteology and Phylogeny of Westphaliasaurus simonsensii, a new plesiosaurid (Sauropterygia) from the Lower Jurassic (Pliensbachian) of Sommersell (Höxter district), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany]. Vol. 79. pp. 56 pp. )

- Smith, Adam Stuart (2007). Anatomy and Systematics of the Rhomaleosauridae (Sauropterygia:Plesiosauria) (PDF) (Thesis). University of Ireland.

- Adam S. Smith; Peggy Vincent (2010). "A new genus of pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Jurassic of Holzmaden, Germany". Palaeontology. 53 (5): 1049–1063. S2CID 54887772.

- Adam S. Smith; Ricardo Araújo & Octávio Mateus (2012). "Lusonectes sauvagei, a new plesiosauroid from the Toarcian (Lower Jurassic) of Alhadas, Portugal". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57 (2): 257–266. S2CID 55764533.

- Adam S. Smith (2015). "Reassessment of 'Plesiosaurus' megacephalus (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, UK". Palaeontologia Electronica. 18 (1): Article number 18.1.20A.

- Sollas, W. J. (1881). "On a new species of Plesiosaurus (P. conybeari) from the Lower Lias of Charmouth, with observations on P. megacephalus". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 37 (1–4): 440–481. S2CID 129977015.

- Storrs, G. W. (1999). "An examination of Plesiosauria (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Niobrara Chalk (upper Cretaceous) of central North America". Univ. Kansas Paleont. Cont. New Series. 11: 15.

- Stukeley, W. (1719). "An account of the impression of the almost entire sceleton of a large animal in a very hard stone, lately presented the Royal Society, from Nottinghamshire". Philosophical Transactions. 30 (360): 963–968. S2CID 186213629.

- Stutchbury, S. (1846). "Description of a new species of Plesiosaurus, in the Museum of the Bristol Institution". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 2 (1–2): 411–417. S2CID 131463215.

- Thulborn, T; Turner, S (1993). "An elasmosaur bitten by a pliosaur". Modern Geology. 18: 489–501.

- Peggy Vincent; Nathalie Bardet & Emanuela Mattioli (2013). "A new pliosaurid from the Pliensbachian (Early Jurassic) of Normandy (Northern France)". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58 (3): 471–485. S2CID 54695631.

- Peggy Vincent & Roger B. J. Benson (2012). "Anningasaura, a basal plesiosaurian (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Lower Jurassic of Lyme Regis, United Kingdom". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (5): 1049–1063. S2CID 86547069.

- Peggy Vincent; Nathalie Bardet; Xabier Pereda Suberbiola; Baâdi Bouya; Mbarek Amaghzaz & Saïd Meslouh (2011). "Zarafasaura oceanis, a new elasmosaurid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco and the palaeobiogeography of latest Cretaceous plesiosaurs". Gondwana Research. 19 (4): 1062–1073. ]

- Watson, D. M. S. (1909). "A preliminary note on two new genera of Upper Liassic plesiosaurs". Memoirs of the Manchester Museum. 54: 1–26.

- Welles, S. P. (1943). "Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with description of new material from California and Colorado". Memoir of the University of California. 13: 125–215.

- Welles, S. P. (1952). "A review of North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs". University of California Publications in the Geological Sciences. 29: 47–144.

- Welles, S. P. (1962). "A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs". University of California Publications in the Geological Sciences. 44: 1–96.

- Winkler, T. C. (1873). "Le Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus, Conyb., du Musée Teyler". Archives du Musée Teyler. 3: 219–233.

- Woodward, H. B. (1893). The Jurassic rocks of Britain. Volume III. The Lias of England and Wales (Yorkshire excepted). Memoir of the Geological Survey of the United Kingdom. London. p. 399.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

Media related to Plesiosauria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Plesiosauria at Wikimedia Commons