Altiplano Cundiboyacense

Altiplano Cundiboyacense | |

|---|---|

Late Pliocene |

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense (Spanish pronunciation:

Etymology

Altiplano in Spanish means "high plain" or "high plateau", the second part is a combination of the departments Cundinamarca and Boyacá.

Geography

• Duitama-Sogamoso Iraca Valley

• Ubaté-Chiquinquirá Valley

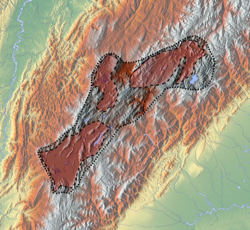

• Bogotá savanna

The limits of the Altiplano are not strictly defined. The high plateau is enclosed by the higher mountains of the Eastern Ranges, with the

Subdivision

The Altiplano is subdivided into three major valleys, from northeast to southwest:

- Iraca Valley

- Ubaté & Chiquinquirá Valley

- Bogotá savanna

Climate

The average temperature on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense is 14 °C (57 °F), ranging from 0 °C (32 °F) to 24 °C (75 °F). The driest months of the year are from December to March, while rain is more common in April, May, September, October and November. From June to August strong winds are present. Hail is common on the Altiplano.[1]

Páramos

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense is surrounded by and contains various Andean unique ecosystems; páramos. 60% of all páramos in the world are situated in Colombia. (Specifically, in the department of Boyacá with the most relative area of páramos).[2] Boyacá is the department where 18.3% of the national total area is located.[3] To the south the Sumapaz Páramo (largest in the world) forms a natural boundary of the Altiplano. Chingaza contains páramo vegetation, as does the most beautiful Ocetá Páramo in the northeast.[4] On the Altiplano the microclimate of the surroundings of Lake Iguaque produces a páramo.

Regional geology

History

Prehistory

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense is formed as part of the uplift of the

The dominating group of top predators and scavengers for decades of millions of years on the continent were the

The biodiversity and former tranquility of the isolated ecosystem changed during the Pliocene, when the

The Late Pleistocene of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense has been analysed in detail through various methods based on fossils found on the Altiplano.

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense is regarded one of eleven archaeological regions of Colombia.

Andean preceramic

Later dated excavations have revealed a transition from a hunter-gatherer society living in

The main part of the diet of the people was formed by

Rock art

Various archaeological sites with

Ceramic pre-Columbian

The ages between 3000 and 1000 years before present corresponds to the Herrera Period, and the era between 1000 BP and 1537, the year of the Spanish conquest, to the Muisca Confederation.[8]

The

The economy of the Muisca was rooted in their

The predominant agricultural product of the Muisca was

Spanish conquest

A delegation of more than 900 men left the tropical city of Santa Marta in April 1536 and went on a harsh expedition through the heartlands of Colombia in search of El Dorado and the civilisation that produced all that precious gold. The leader of the first and main expedition under

The conquest of the Muisca on the Altiplano started in March 1537, when the greatly reduced troops of De Quesada entered Muisca territories in Chipatá, the first settlement they founded on March 8. The expedition went further inland and up the slopes of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense into later Boyacá and Cundinamarca. The towns of Moniquirá (Boyacá) and Guachetá and Lenguazaque (Cundinamarca) were founded before the conquistadors arrived at the northern edge of the Bogotá savanna in Suesca.[24] continued to Lenguazaque that was founded the next day,[25][26] En route towards the domain of zipa Tisquesusa, the Spanish founded Cajicá and Chía.[27][28] In April 1537 they arrived at Funza, where Tisquesusa was beaten by the Spanish. This formed the onset for further expeditions, starting a month later towards the eastern Tenza Valley and the northern territories of zaque Quemuenchatocha. On August 20, 1537, the zaque was submitted in his bohío in Hunza. The Spanish continued their journey northeastward into the Iraca Valley, where the iraca Sugamuxi fell to the Spanish troops and the Sun Temple was accidentally burned by two soldiers of the army of De Quesada in early September.[23]

Meanwhile, other soldiers from the conquest expedition went south and conquered Pasca and other settlements. The Spanish leader returned with his men to the Bogotá savanna and planned new conquest expeditions executed in the second half of 1537 and first months of 1538. On August 6, 1538, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada founded Bogotá as the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada, named after his home region of Granada, Spain. That same month, on August 20, the zipa who succeeded his brother Tisquesusa upon his death; Sagipa, allied with the Spanish to fight the Panche, eternal enemies of the Muisca in the southwest. In the Battle of Tocarema, the allied forces claimed victory over the bellicose western neighbours. In late 1538, other conquest undertakings resulted in more founded settlements in the heart of the Andes. Two other expeditions that were taking place at the same time; of De Belalcázar from the south and Federmann from the east, reached the newly founded capital and the three leaders embarked in May 1539 on a ship on the Magdalena River that took them to Cartagena and from there back to Spain. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada had installed his younger brother Hernán as new governor of Bogotá and the latter organised new conquest campaigns in search of El Dorado during the second half of 1539 and 1540. His captain Gonzalo Suárez Rendón founded Tunja on August 6, 1539, and captain Baltasar Maldonado, who had served under De Belalcázar, defeated the cacique of Tundama at the end of 1539. The last zaque Aquiminzaque was decapitated in early 1540, establishing the new rule over the former Muisca Confederation.[23]

New Kingdom of Granada

Modern day

Present-day, due to the large population and agriculture of the Altiplano, the original vegetation is at risk.[29]

Timeline of inhabitation

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

|

Cities

Most important city of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense is the Colombian capital Bogotá. Other cities are, from northeast to southwest:

- Sogamoso

- Duitama

- Chiquinquirá

- Villa de Leyva

- Tunja

- Ubaté

- Suesca

- Tocancipá

- Zipaquirá

- Cajicá

- Chía

- Facatativá

- Soacha

Hydrology

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense hosts a number of rivers and lakes.

Rivers

- left

- Teusacá River

- Juan Amarillo River

- Fucha River

- Tunjuelo River

- Soacha River

- right

- Orinoco Basin, via Meta River

Lakes

Natural

- Lake Tota, largest lake of Colombia

- Lake Fúquene

- Lake Guatavita

- Lake Herrera

- Lake Iguaque

- Siecha Lakes

- Lake Suesca

Artificial

- La Copa Reservoir

- El Muña Reservoir

- Neusa Reservoir

- San Rafael Reservoir

- Sisga Reservoir

- Lake Sochagota

- Tominé Reservoir

- Lake Herrera (since 1973)

Waterfalls

Wetlands

Altiplanos in Latin America

| Latin America | Valley of Mexico | Altiplano Cundiboyacense | Altiplano Boliviano |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Paleolake | Lake Texcoco | Lake Humboldt | Lake Tauca |

| Human occupation (yr BP) | 11,100 – Tocuila | 12,560 – El Abra | 3530 – Tiwanaku |

| Pre-Columbian civilisation | Aztec | Muisca | Inca |

| Today | |||

| Elevation | 2,236 m (7,336 ft) | 2,780 m (9,120 ft) | 3,800 m (12,500 ft) |

| Area | 9,738 km2 (3,760 sq mi) | 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) | 175,773 km2 (67,866 sq mi) |

| References |

See also

- Altiplano Nariñense

- Andes, Bogotá savanna

- Eastern Hills, Bogotá

- Muisca, Muisca Confederation, Ocetá Páramo

- Tenza Valley, Chicamocha Canyon

References

- ^ Climates of various cities of Colombia (in Spanish)

- ^ Five unmissable Colombian páramos begging to be explored

- ^ Nieto Escalante et al., 2010, p.75

- ^ Wills et al., 2001, p.117

- ^ Hogenboom, Melissa (2015). "There was once a marine reptile that had four nostrils". BBC Earth. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- ^ Marshall, Larry G. (2004). "The Terror Birds of South America" (PDF). Scientific American. 14: 82–89. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- ^ Map of archaeological regions of Colombia – Banco de la República from Colombia Prehispánica, 1989 (in Spanish)

- ^ a b c Botiva Contreras, 1989

- ^ Cardale de Schrimpff, 1985

- ^ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.64-77

- ^ Soatá in the Paleobiology database

- ^ Correal Urrego, 1990, p.79

- ^ Petroglyphs on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense (in Spanish)

- ^ Martínez & Mendoza, 2014

- ^ Langebaek et al., 2011, p.17

- ^ Daza, 2013, pp.27–28

- ^ Kruschek, 2003, p.5

- ^ Langebaek, 1985, p.4

- ^ Schrimpff, 1985, p.106

- ^ Daza, 2013, p. 23

- ^ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.207

- ^ García, 2012, p.43

- ^ a b c d Conquista rápida y saqueo cuantioso de Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (in Spanish)

- ^ Official website Guachetá Archived 2017-07-09 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- ^ Official website Lenguazaque (in Spanish)

- ^ Official website Suesca (in Spanish)

- ^ History Cajicá (in Spanish)

- ^ De Quesada celebrated the Holy Week in Chia (in Spanish)

- ^ Calvachi Zambrano, 2012

- ^ Acosta Ochoa, 2007, p.9

- ^ Bradbury, 1971, p.181

- ^ Rodríguez & Morales, 2010, p.2

- ^ Aceituno & Rojas, 2012, p.127

- ^ Pérez Preciado, 2000, p.6

- ^ Area Altiplano Cundiboyacense approximately 25,000 square kilometres (9,700 sq mi)

- ^ Ponce Sanginés, 1972, p.90

- ^ Datos Generales de Bolivia (in Spanish)

- ^ Junta Directiva, 1972, p.71

Bibliography

General

- Botiva Contreras, Álvaro; Groot de Mahecha, Ana María; Herrera, Eleonor; Mora, Santiago (1989). Colombia Prehispánica – La Altiplanicie Cundiboyacense – Prehispanic Colombia – the Altiplano Cundiboyacense (in Spanish). Biblioteca Luís Ángel Arango. Archived from the original on 2016-08-05. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

Geology, geography and climate

- Barney Duran, Victoria Eugenia (2011). Biodiversidad y ecogeografía del género Lupinus (Leguminosae) en Colombia (PDF) (Masters thesis). Universidad Nacional. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- Calvachi Zambrano, Byron (2012). "Los ecosistemas semisecos del altiplano cundiboyacense, bioma azonal singular de Colombia, en gran riesgo de desaparición – The semi-arid ecosystems of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, bioma of Colombia, at great risk of disappearance". Mutis (in Spanish). 2 (2): 26–59. ISSN 2256-1498.

- Hoorn, Carina; Guerrero, Javier; Sarmiento, Gustavo A.; Lorente, Maria A. (1995). "Andean tectonics as a cause for changing drainage patterns in Miocene northern South America". .

- Hoyos, Natalia; Monsalve, O.; Berger, G.W.; Antinao, J.L.; Giraldo, H.; Silva, C.; Ojeda, G.; Bayona, G.; and C. Montes, J. Escobar (2015). "A climatic trigger for catastrophic Pleistocene–Holocene debris flows in the Eastern Andean Cordillera of Colombia". doi:10.1002/jqs.2779.

- Monsalve, Maria Luisa; Rojas, Nadia R.; Velandia P., Francisco A.; Pintor, Iraida; Martínez, Lina Fernanda (2011). "Caracterización geológica del cuerpo volcánico de Iza, Boyacá – Colombia". Boletín de Geología: 117–130.

- Montoya Arenas, Diana María; Reyes Torres, Germán Alfonso (2005). Geología de la Sabana de Bogotá. INGEOMINAS.

- Nieto Escalante, Juan Antonio; Sepulveda Fajardo, Claudia Inés; Sandoval Sáenz, Luis Fernando; Siachoque Bernal, Ricardo Fabian; Fajardo Fajardo, Jair Olando; Martínez Díaz, William Alberto; Bustamante Méndez, Orlando; Oviedo Calderón, Diana Rocio (2010). Geografía de Colombia – Geography of Colombia (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi. ISBN 978-958-8323-38-1.

- Sarmiento Rojas, L.F.; Van Wees, J.D.; Cloetingh, S. (2006). "Mesozoic transtensional basin history of the Eastern Cordillera, Colombian Andes: Inferences from tectonic models". .

Prehistory and preceramic

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne (1985). Ocupaciones humanas en el Altiplano Cundiboyacense – Human occupations on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense (in Spanish). Biblioteca Luís Ángel Arango. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo (1990). Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges (PDF) (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - Groot de Mahecha, Ana María (1992). Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente – Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present. Banco de la República. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Silva Celis, Eliécer (1962). "Pinturas rupestres precolombinas de Sáchica, Valle de Leiva – Pre-Columbian rock art of Sáchica, Leyva Valley". Revista Colombiana de Antropología (in Spanish). X: 9–36. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Villarroel, Carlos; Concha, Ana Elena; Macía, Carlos (2001). "El Lago Pleistoceno de Soatá (Boyacá, Colombia): Consideraciones estratigráficas, paleontológicas y paleoecológicas". Geología Colombiana. 26. Universidad Nacional de Colombia: 79–93.

Herrera

- Paepe, Paul de; Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne (1990). "Resultados de un estodio petrológico de cerámicas del Periodo Herrera provenientes de la Sabana de Bogotá y sus implicaciones arqueológicas – Results of a petrological study of ceramics form the Herrera Period coming from the Bogotá savanna and its archaeological implications". Boletín Museo del Oro (in Spanish). Museo del Oro: 99–119. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

The Salt People

- Argüello García, Pedro María (2015). Subsistence economy and chiefdom emergence in the Muisca area. A study of the Valle de Tena (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Boada Rivas, Ana María (2006). Patrones de asentamiento regional y sistemas de agricultura intensiva en Cota y Suba, Sabana de Bogotá (Colombia) – Regional settlement patterns and intensive agricultural systems in Cota and Suba, Bogotá savanna (Colombia) (in Spanish). ISBN 9789589515389. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- .

- Daza, Blanca Ysabel (2013). Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre Colombia y España - History of the integration process of foods between Colombia and Spain (PhD thesis) (in Spanish). Barcelona, Spain: Universitat de Barcelona.

- Francis, John Michael (1993). "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (Masters thesis). University of Alberta.

- García, Jorge Luis (2012). The Foods and crops of the Muisca: a dietary reconstruction of the intermediate chiefdoms of Bogotá (Bacatá) and Tunja (Hunza), Colombia (PDF) (Masters thesis). University of Central Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-03. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ISBN 978-958-719-046-5.

- Kruschek, Michael H. (2003). The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Banco de la República. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ISBN 978-958-14-0368-4.

Colonial period

- Francis, John Michael (2002). "Población, enfermedad y cambio demográfico, 1537-1636. Demografía histórica de Tunja: Una mirada crítica". Fronteras de la Historia. 7: 13–76. .

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik (1995c). "De cómo convertir a los indios y de porqué no lo han sido. Juan de Varcarcel y la idolatría en el altiplano cundiboyacense a finales del siglo XVII – How to convert the indians and why they didn't. Juan de Varcarcel and the idolatry on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense at the end of the 17th century". Revista de Antropología y Arqueología (in Spanish). 11: 187–234.

- Martínez Martín, A. F.; Manrique Corredor, E. J. (2014). "Alimentación prehispánica y transformaciones tras la conquista europea del altiplano cundiboyacense, Colombia" [Pre-Columbian Food and Transformations after European Conquest of Cundiboyacense High Plateau, Colombia]. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte (in Spanish). 41: 96–111. ISSN 0124-5821.

Altiplanos in the Americas

Mexico

- Acosta Ochoa, Guillermo (2007). "Las ocupaciones precerámicas de la Cuenca de México – del poblamiento a las primeras sociedades agrícolas" (PDF). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- Bradbury, John P (1971). "Paleolimnology of Lake Texcoco, Mexico – evidence from diatoms". .

- Rodríguez Tapia, Lilia; Morales Novelo, Jorge A. (2012). "Integración de un sistema de cuentas económicas e hídricas en la Cuenca del Valle de México" (PDF). Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

Colombia

- Aceituno Bocanegra, Francisco Javier; Rojas Mora, Sneider (2012). "Del Paleoindio al Formativo: 10.000 años para la historia de la tecnología lítica en Colombia – From the Paleoindian to the Formative Stage: 10,000 years for the history of lithic technology in Colombia" (PDF). Boletín de Antropología, Universidad de Antioquia. 28 (43): 124–156. ISSN 0120-2510. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- Pérez Preciado, Alfonso (2000). La estructura ecológica principal de la Sabana de Bogotá. Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia.

Bolivia

- Ponce Sanginés, Carlos (1972). Tiwanaku: Espacio, tiempo y cultura (PDF). Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- Junta Directiva, undécima reunión anual: resoluciones y documentos. IICA Biblioteca Venezuela. 1972. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

Visitor attractions

- Hurtado Caro, José Próspero (2012). Monguí – Boyacá – Colombia.

- Wills, Fernando; et al. (2001). Nuestro patrimonio – 100 tesoros de Colombia – Our heritage – 100 treasures of Colombia (in Spanish). Tiempo Casa Editorial. ISBN 958-8089-16-6.