Anti-imperialism

An influential movement independent of the

The phrase gained a wide currency after the

Theory

In the late 1870s, the term "imperialism" was introduced to the English language by opponents of the aggressively imperial policies of British Prime Minister

The relationships among

Hobson

Hobson was also influential in liberal circles, especially the British Liberal Party.[14] Historians Peter Duignan and Lewis H. Gann argue that Hobson had an enormous influence in the early 20th century that caused widespread distrust of imperialism:

Hobson's ideas were not entirely original; however his hatred of moneyed men and monopolies, his loathing of secret compacts and public bluster, fused all existing indictments of imperialism into one coherent system....His ideas influenced German nationalist opponents of the British Empire as well as French Anglophobes and Marxists; they colored the thoughts of American liberals and isolationist critics of colonialism. In days to come they were to contribute to American distrust of Western Europe and of the British Empire. Hobson helped make the British averse to the exercise of colonial rule; he provided indigenous nationalists in Asia and Africa with the ammunition to resist rule from Europe.[15]

On the positive side, Hobson argued that domestic social reforms could cure the international disease of imperialism by removing its economic foundation. Hobson theorized that state intervention through taxation could boost broader consumption, create wealth and encourage a peaceful multilateral world order. Conversely, should the state not intervene, rentiers (people who earn income from property or securities) would generate socially negative wealth that fostered imperialism and protectionism.[16][17]

Political movement

As a self-conscious political movement, anti-imperialism originated in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in opposition to the growing European

International context

United States

An early use of the term "anti-imperialist" occurred after the United States entered the Spanish–American War in 1898.[19] Most activists supported the war itself, but opposed the annexation of new territory, especially the Philippines.[20] The Anti-Imperialist League was founded on June 15, 1898, in Boston in opposition of the acquisition of the Philippines, which would happen anyway. The anti-imperialists opposed the expansion because they believed imperialism violated the credo of republicanism, especially the need for "consent of the governed". Appalled by American imperialism, the Anti-Imperialist League, which included famous citizens such as Andrew Carnegie, Henry James, William James and Mark Twain, formed a platform which stated:

We hold that the policy known as imperialism is hostile to liberty and tends toward militarism, an evil from which it has been our glory to be free. We regret that it has become necessary in the land of Washington and Lincoln to reaffirm that all men, of whatever race or color, are entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We maintain that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. We insist that the subjugation of any people is "criminal aggression" and open disloyalty to the distinctive principles of our Government... We cordially invite the cooperation of all men and women who remain loyal to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.[21]

Fred Harrington states that "the anti-imperialist's did not oppose expansion because of commercial, religious, constitutional, or humanitarian reasons but instead because they thought that an imperialist policy ran counter to the political doctrines of the Declaration of Independence, Washington's Farewell Address, and Lincoln's Gettysburg Address".[22][23][24]

An important influence on American intellectuals was the work of British writer

Hobson's ...hatred of moneyed men and monopolies, his loathing of secret compacts and public bluster, fused all existing indictments of imperialism into one coherent system....His ideas influenced German nationalist opponents of the British Empire as well as French Anglophobes and Marxists; they colored the thoughts of American liberals and isolationist critics of colonialism. In days to come they were to contribute to American distrust of Western Europe and of the British Empire. Hobson helped make the British averse to the exercise of colonial rule; he provided indigenous nationalists in Asia and Africa with the ammunition to resist rule from Europe.[15]

The American rejection of the League of Nations in 1919 was accompanied with a sharp American reaction against European imperialism. American textbooks denounced imperialism as a major cause of the World War. The uglier aspects of British colonial rule were emphasized, recalling the long-standing anti-British sentiments in the United States.[25]

In Britain and Canada

Anti-imperialism within Britain emerged in the 1890s, especially from within the

Moderately active anti-imperial movements emerged in Canada and Australia. The French Canadians were hostile to British expansion whilst in Australia, it was the Irish Catholics who were opposed.[30] French Canadians argue that Canadian nationalism was the proper and true goal and it sometimes conflicted with loyalty to the British Empire. Many French Canadians claimed that they would fight for Canada but would not fight for the Empire.[31]

Protestant Canadians, typically of British descent, generally supported British imperialism enthusiastically. They sent thousands of volunteers to fight alongside British and imperial forces against the Boers and in the process identified themselves even more strongly with the British Empire.[32] A little opposition also came from some English immigrants such as the intellectual leader Goldwin Smith.[33] In Canada, the Irish Catholics were fighting the French Canadians for control of the Catholic Church, so the Irish generally supported the pro-British position.[34] Anti-imperialism also grew rapidly in India and formed a core element of the demand by Congress for independence.[citation needed]

Leninism and Marxism–Leninism

In the mid-19th century, Karl Marx mentioned imperialism to be part of the prehistory of the capitalist mode of production in Das Kapital (1867–1894). Much more important was Vladimir Lenin, who defined imperialism as "the highest stage of capitalism", the economic stage in which monopoly finance capital becomes the dominant application of capital.[35] As such, said financial and economic circumstances impelled national governments and private business corporations to worldwide competition for control of natural resources and human labour by means of colonialism.[36]

The

In Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), Lenin outlined the five features of capitalist development that lead to imperialism:

- Concentration of production and capital leading to the dominance of national and multinational monopolies and cartels.

- Industrial capital as the dominant form of capital has been replaced by finance capital, with the industrial capitalists increasingly reliant on capital provided by monopolistic financial institutions. "Again and again, the final word in the development of banking is monopoly".

- The export of the aforementioned finance capital is emphasized over the export of goods.

- The economic division of the world by multinational cartels.

- The political division of the world into colonies by the great powers, in which the great powers monopolise investment.[38]

Generally, the relationship among Marxist-Leninists and radical, left-wing organisations who are

In the 20th century, the Soviet Union represented themselves as the foremost enemy of imperialism and thus politically and financially supported Third World revolutionary organisations who fought for national independence. This was accomplished through the export of both financial capital and Soviet military apparatuses, with the Soviet Union sending military advisors to Ethiopia, Angola, Egypt and Afghanistan.

However,

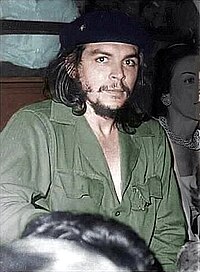

About the nature of imperialism and how to oppose and defeat it, Che Guevara said:

imperialism is a world system, the last stage of capitalism—and it must be defeated in a world confrontation. The strategic end of this struggle should be the destruction of imperialism. Our share, the responsibility of the exploited and underdeveloped of the world, is to eliminate the foundations of imperialism: our oppressed nations, from where they extract capitals, raw materials, technicians, and cheap labor, and to which they export new capitals—instruments of domination—arms and all kinds of articles; thus submerging us in an absolute dependence.

— Che Guevara, Message to the Tricontinental, 1967[42]

Trotskyism

The concept of permanent war economy originated in 1945 with an article by

The concept has been a core tenet of the British

Opposition to Soviet imperialism

The nations which were part of the Soviet sphere of influence were nominally independent countries with separate governments that set their own policies, but those policies had to stay within certain limits decided by the Soviet Union. These limits were enforced by the threat of intervention by Soviet forces, and later the

The Soviet Union exhibited tendencies common to historic empires.[46][47] The notion of "Soviet empire" often refers to a form of "classic" or "colonial" empire with communism only replacing conventional imperial ideologies such as Christianity or monarchy, rather than creating a revolutionary state. Academically the idea is seen as emerging with former CIA asset Richard Pipes' 1957 book The Formation of the Soviet Union: Communism and Nationalism, 1917–1923, but it has been reinforced, along with several other views, in continuing scholarship.[48]: 41 Several scholars hold that the Soviet Union was a hybrid entity containing elements common to both multinational empires and nation states.[46] The Soviet Union practiced colonialism similar to conventional imperial powers.[47][49][50][51][52][53][54]

Islamic anti-imperialism

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed the rise of numerous

These anti-colonial movements inspired the rise of

After Rashid Rida, the mantle of Islamist anti-imperialism was spearheaded by the

In his book "Al Jihad Fil Islam", South Asian revolutionary Islamist scholar Abul A'la Mawdudi made a comprehensive religious refutation of imperialism

"the basic quality of imperialism is the dominance of one particular nation or country... Thus, the doors of imperialism remain closed to people of other nationalities and for this reason, they can play no major role in running its affairs. This gives rise to the development of other faults in the system and characters of the subject nation. They develop a weakness of character, lose self-esteem and the sense of righteousness. Even if the ruling nation does not treat the subjects with outright cruelty and arrogance, their (the subject nation’s) character sinks to such a low ebb of ignobility that they become quite incapable of striving for attaining and maintaining self-rule for a very long time."

The Indian

In the worldview of Egyptian Jihadist theoretician Sayyid Qutb, imperialist policies of the secular Western regimes were a continuation of their historical "Crusading Spirit".[63] In his commentary of the Qur'anic verse 2:120 "{Never will the Jews be pleased with you, (O Prophet), nor the Christians until you follow their way..}", Sayyid Qutb writes:

"The conflict between the Judeo-Christian world on the one side, and the Muslim community on the other, remains in essence one of ideology, although over the years it has appeared in various guises and has grown more sophisticated and, at times, more insidious. We have seen the original ideological conflict succeeded by economic, political and military confrontation, on the basis that 'religious' or 'ideological' conflicts are outdated and are usually prosecuted by 'fanatics' and backward people. Unfortunately, some naïve and confused Muslims have fallen for this stratagem and persuaded themselves that the religious and ideological aspects of the conflict are no longer relevant. But in reality world Zionism and Christian Imperialism, as well as world Communism, are conducting the fight against Islam and the Muslim community, first and foremost, on ideological grounds... The confrontation is not over control of territory or economic resources, or for military domination. If we believe that, we would play into our enemies’ hands and would have no one but ourselves to blame for the consequences."

Liberal anti-imperialism

Sometimes liberals also oppose imperialism. However, liberal anti-imperialists are distinct from socialist anti-imperialists because they do not support anti-capitalism.[65]

Some modern liberals in the United States, including Dennis Kucinich, support non-interventionism.[citation needed]

Criticism

Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt assert that traditional anti-imperialism is no longer relevant. In the book Empire,[68] Negri and Hardt argue that imperialism is no longer the practice or domain of any one nation or state. Rather, they claim, the "Empire" is a conglomeration of all states, nations, corporations, media, popular and intellectual culture and so forth; and thus, traditional anti-imperialist methods and strategies can no longer be applied against them.[citation needed]

The

See also

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-British sentiment

- Anti-French sentiment

- Anti-Western sentiment

- Colonialism

- Decentralization

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Indigenism

- Internationalism (politics)

- Irish nationalism (Irish republicanism)

- Korean nationalism

- League against Imperialism

- Left-wing nationalism

- Localism (politics)

- National liberation wars

- National self-determination

- Postcolonialism

Notes

References

- ^ Richard Koebner and Helmut Schmidt, Imperialism: The Story and Significance of a Political Word, 1840–1960 (2010).

- ISBN 9780190087470. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-04. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ISBN 978-1-138-83939-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-7609-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ISBN 978-0-7103-0469-8.

- ISBN 978-0-691-19522-3.

- ISBN 978-9971-69-359-6.

- ISBN 978-1-138-83939-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4039-6556-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-04. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ a b Richard Koebner and Helmut Schmidt, Imperialism: The Story and Significance of a Political Word, 1840–1960 (2010)

- ^ Mark F. Proudman, "Words for Scholars: The Semantics of 'Imperialism'". Journal of the Historical Society, September 2008, Vol. 8 Issue 3, p395-433

- ^ D. K. Fieldhouse, "Imperialism": An Historiographical Revision", South African Journal of Economic History, March 1992, Vol. 7 Issue 1, pp 45–72

- ^ G.K. Peatling, “Globalism, Hegemonism and British Power: J. A. Hobson and Alfred Zimmern Reconsidered”, History, July 2004, Vol. 89 Issue 295, pp. 381–98

- ^ David Long, Towards a new liberal internationalism: the international theory of JA Hobson (1996).

- ^ ISBN 9780817916930. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ^ P. J. Cain, "Capitalism, Aristocracy and Empire: Some 'Classical' Theories of Imperialism Revisited", Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, March 2007, Vol. 35 Issue 1, pp 25–47

- ^ G.K. Peatling, "Globalism, Hegemonism and British Power: J. A. Hobson and Alfred Zimmern Reconsidered", History, July 2004, Vol. 89 Issue 295, pp 381–398

- ^ Harrington, 1935

- ^ Robert L. Beisner, Twelve against Empire: The Anti-Imperialists, 1898–1900 (1968)

- ^ Julius Pratt, Expansionists of 1898: The Acquisition of Hawaii and the Spanish Islands (1936) pp 266–78

- ^ "Platform of the American Antilmperialist League, 1899". Fordham University. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Harrington, 1935, pp 211–12

- ^ Richard E. Welch, Jr., Response to Imperialism: The United States and the Philippine-American War, 1899–1902 (1978)

- ^ E. Berkeley Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States: The Great Debate, 1890–1920. (1970)

- ISBN 9780801400971. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ^ Robert Livingston Schuyler, "The rise of anti-imperialism in England." Political science quarterly 37.3 (1922): 440–471. in JSTOR Archived 2016-11-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gregory Claeys, Imperial Sceptics: British Critics of Empire, 1850–1920 (2010) excerpt

- ^ Bernard Porter, Critics of Empire: British Radical Attitudes to Colonialism in Africa 1895–1914 (1968).

- ^ Sarah Britton, "‘Come and See the Empire by the All Red Route!’: Anti-Imperialism and Exhibitions in Interwar Britain." History Workshop Journal 69#1 (2010).

- ^ C. N. Connolly, "Class, birthplace, loyalty: Australian attitudes to the Boer War." Australian Historical Studies 18.71 (1978): 210–232.

- ^ Carl Berger, ed. Imperialism and Nationalism, 1884–1914: a conflict in Canadian thought (1969).

- ^ Gordon L. Heath, War with a Silver Lining: Canadian Protestant Churches and the South African War, 1899–1902 (McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP, 2009).

- ^ R. Craig Brown, "Goldwin Smith and Anti‐imperialism." Canadian Historical Review 43.2 (1962): 93–105.

- ^ Mark G. McGowan, "The De-Greening of the Irish: Toronto’s Irish‑Catholic Press, Imperialism, and the Forging of a New Identity, 1887–1914." Historical Papers/Communications historiques 24.1 (1989): 118–145.

- ^ "Imperialism", The Penguin Dictionary of International Relations (1998), by Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham. p. 244.

- ^ a b "Colonialism", The Penguin Dictionary of International Relations (1998) Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham, p. 79.

- ^ "Imperialism", The Penguin Dictionary of International Relations (1998) Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham, p. 79.

- ^ "Lenin: Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism". Archived from the original on 2008-01-10. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ^ "Weekly Worker 403 Thursday October 11 2001". www.cpgb.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 July 2002. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Battling Western Imperialism: Mao, Stalin, and the United States (1997), by Michael M. Sheng. p.00.

- ^ Marxist Theories of Imperialism: A Critical Survey (1990), by Anthony Brewer. p. 293.

- ^ Che Guevara: Message to the Tricontinental Archived 2018-01-27 at the Wayback Machine Spring of 1967.

- ISSN 0301-7605.

- ^ See Peter Drucker, Max Schachtman and his Left. A Socialist Odyssey through the 'American Century', Humanities Press 1994, p. xv, 218; Paul Hampton, "Trotskyism after Trotsky? C'est moi!", in Workers Liberty, vol 55, April 1999, p. 38

- ^ "Tony Cliff: Permanent War Economy (May 1957)". www.marxists.org.

- ^ S2CID 156553569.

Dave, Bhavna (2007). Kazakhstan: Ethnicity, Language and Power. Abingdon, New York: Routledge. - ^ JSTOR 20031013.

- ISBN 978-963-9776-68-5.

- ISBN 978-0367-2345-4-6.

- ^ Cucciolla, Riccardo (23 March 2019). "The Cotton Republic: Colonial Practices in Soviet Uzbekistan?". Central Eurasian Studies Society. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ISBN 978-3849-8114-7-1.

- S2CID 159664992.

- ^ Thompson, Ewa (2014). "It is Colonialism After All: Some Epistemological Remarks" (PDF). Teksty Drugie (1). Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences: 74.

- ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the originalon 2021-11-09. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ISBN 978-0-19-966831-1.

- ISBN 978-1-108-41833-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8133-2691-7.

- ISBN 978-0-415-63988-0.

- S2CID 253068552.

- ^ A'la Maududi, Abul. Al Jihad Fil Islam [Jihad in Islam] (PDF) (in Urdu). Translated by Rafatullah Shah, Syed. Lahore: Syed Khalid Farooq Maududi. pp. 63–65. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-24. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ "Jamaat to launch nation-wide 'anti-imperialism' campaign". Zee News. December 10, 2009. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Borowski, Audrey (2015). "Al Qaeda and ISIS: From Revolution to Apocalypse". Philosophy Now. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022.

- ISBN 0-9548665-1-7.

- ^ Qutb, Sayyid (7 December 2016). Fi Zilal al-Quran [In the Shade of the Qur'an] (in Arabic). pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b "정부, '日경제보복' WTO 긴급 상정…"자유무역 원칙 위배"". 연합뉴스 TV. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- 한겨레. 14 August 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "이재명 측 "한복 넘보는 중국 문화공정, 이대로 방치하지 않겠다"". 5 February 2022.

- ISBN 0-674-00671-2

- ^ Mälksoo, Maria. "The postcolonial moment in Russia’s war against Ukraine." Journal of Genocide Research 25.3–4 (2023): 471–481.

Further reading

- Ali, Tariq et al. Anti-Imperialism: A Guide for the Movement ISBN 1-898876-96-7.

- Boittin, Jennifer Anne. Colonial Metropolis: The Urban Grounds of Anti-Imperialism and Feminism in Interwar Paris (2010).

- Brendon, Piers. "A Moral Audit of the British Empire." History Today, (Oct 2007), Vol. 57 Issue 10, pp 44–47, online at EBSCO.

- Brendon, Piers. The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781–1997 (2008) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cain, P. J. and A.G. Hopkins. British Imperialism, 1688–2000 (2nd ed. 2001), 739pp, detailed economic history that presents the new "gentlemanly capitalists" thesis excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Castro, Daniel, Walter D.Mignolo, and Irene Silverblatt. Another Face of Empire: Bartolomé de Las Casas, Indigenous Rights, and Ecclesiastical Imperialism (2007) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, Spanish colonies.

- Cullinane, Michael Patrick. Liberty and American Anti-Imperialism, 1898–1909. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Ferguson, Niall. Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (2002), excerpt and text search Archived 2020-11-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- Friedman, Jeremy, and Peter Rutland. "Anti-imperialism: The Leninist Legacy and the Fate of World Revolution." Slavic Review 76.3 (2017): 591–599.

- Griffiths, Martin, and Terry O'Callaghan, and Steven C. Roach 2008. International Relations: The Key Concepts. Second Edition. New Millan.

- Hamilton, Richard. President McKinley, War, and Empire (2006).

- Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Empire (2001), influential statement from the left.

- Harrington, Fred H. "The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898–1900", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Sep., 1935), pp. 211–230 in JSTOR Archived 2018-09-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- Herman, Arthur. Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age (2009) [excerpt and text search].

- Hobson, J.A. Imperialism: A Study (1905) except and text search 2010 edition Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (1997).

- Karsh, Efraim. Islamic Imperialism: A History (2007) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ness, Immanuel, and Zak Cope, eds. The Palgrave encyclopedia of imperialism and anti-imperialism (2 vol. 2016). 1456pp

- Olson, James S. et al., eds. Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism (1991) online edition Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Owen, Nicholas. The British Left and India: Metropolitan Anti-Imperialism, 1885–1947 (2008) excerpt and text search Archived 2023-02-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Polsgrove, Carol. Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause (2009).

- Porter, Bernard. The Lion's Share: A History of British Imperialism 1850–2011 (4th ed. 2012), Wide-ranging general history; strong on anti-imperialism.

- Proudman, Mark F.. "Words for Scholars: The Semantics of 'Imperialism'". Journal of the Historical Society, September 2008, Vol. 8 Issue 3, p395-433.

- Sagromoso, Domitilla, James Gow, and Rachel Kerr. Russian Imperialism Revisited: Neo-Empire, State Interests and Hegemonic Power (2010).

- Thornton, A.P. The Imperial Idea and its Enemies (2nd ed. 1985)

- Tompkins, E. Berkeley, ed. Anti-Imperialism in the United States: The Great Debate, 1890—1920. (1970) excerpts from primary and secondary sources.

- Tyrell, Ian and Jay Sexton, eds. Empire's Twin: U.S. anti-imperialism from the founding era to the age of terrorism (2015).

- Wang, Jianwei. "The Chinese interpretation of the concept of imperialism in the anti-imperialist context of the 1920s.," Journal of Modern Chinese History (2012) 6#2 pp 164–181.

External links

- The Anti-Imperialists, A Web based guide to American Anti-Imperialism.

- CWIHP at the Wilson Center for Scholars: Primary Document Collection on Anti-Imperialism in the Cold War Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pacific Northwest Antiwar and Radical History Project, multimedia collection of photographs, video, oral histories and essays.

- Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism by V.I. Lenin Full text at marxists.org.

- How Imperialist 'Aid' Blocks Development in Africa by Thomas Sankara, The Militant, April 13, 2009.

- Daniel Jakopovich, In the Belly of the Beast: Challenging US Imperialism and the Politics of the Offensive.