Peace movement

This article needs to be updated. (June 2023) |

A peace movement is a

A global affiliation of activists and political interests viewed as having a shared purpose and constituting a single movement has been called "the peace movement", or an all-encompassing "anti-war movement". Seen from this perspective, they are often indistinguishable and constitute a loose, responsive, event-driven collaboration between groups motivated by humanism, environmentalism, veganism, anti-racism, feminism, decentralization, hospitality, ideology, theology, and faith.

The ideal of peace

Ideas differ about what "peace" is (or should be), which results in a number of movements seeking different ideals of peace. Although "anti-war" movements often have short-term goals, peace movements advocate an ongoing lifestyle and a proactive government policy.[1]

It is often unclear whether a movement, or a particular protest, is against war in general or against one's government's participation in a war. This lack of clarity (or long-term continuity) has been part of the strategy of those seeking to end a war, such as the Vietnam War.

Elements of the global peace movement seek to guarantee health security by ending war and ensure what they view as basic human rights, including the right of all people to have access to clean air, water, food, shelter and health care. Activists seek social justice in the form of equal protection and equal opportunity under the law for groups which had been disenfranchised.

The peace movement is characterized by the belief that humans should not wage war or engage in ethnic cleansing about language, race, or natural resources, or engage in ethical conflict over religion or ideology. Long-term opponents of war are characterized by the belief that military power does not equal justice.

The peace movement opposes the proliferation of dangerous technology and

These movements led to the formation of Green parties in a number of democratic countries in the late 20th century. The peace movement has influenced these parties in countries such as Germany.

History

Peace and Truce of God

The first mass peace movements were the Peace of God (

Peace churches

The Reformation gave rise to a number of Protestant sects beginning in the 16th century, including the peace churches. Foremost among these churches were the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), Amish, Mennonites, and the Church of the Brethren. The Quakers were prominent advocates of pacifism, who had repudiated all forms of violence and adopted a pacifist interpretation of Christianity as early as 1660.[3] Throughout the 18th-century wars in which Britain participated, the Quakers maintained a principled commitment not to serve in an army or militia and not pay the alternative £10 fine.

18th century

The major 18th-century peace movements were products of two schools of thought which coalesced at the end of the century. One, rooted in the secular Age of Enlightenment, promoted peace as the rational antidote to the world's ills; the other was part of the evangelical religious revival which had played an important role in the campaign for the abolition of slavery. Representatives of the former included Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in Extrait du Projet de Paix Perpetuelle de Monsieur l'Abbe Saint-Pierre (1756);[4] Immanuel Kant in Thoughts on Perpetual Peace,[5] and Jeremy Bentham, who proposed the formation of a peace association in 1789. One representative of the latter was William Wilberforce; Wilberforce thought that by following the Christian ideals of peace and brotherhood, strict limits should be imposed on British involvement in the French Revolutionary Wars.[6]

19th century

During the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1814), no formal peace movement was established in Britain until hostilities ended. A significant grassroots peace movement, animated by universalist ideals, emerged from the perception that Britain fought in a reactionary role and the increasingly visible impact of the war on the nation's welfare in the form of higher taxes and casualties. Sixteen peace petitions to Parliament were signed by members of the public; anti-war and anti-Pitt demonstrations were held, and peace literature was widely disseminated.[7]

The first formal peace movements appeared in 1815 and 1816. The first movement in the United States was the New York Peace Society, founded in 1815 by theologian David Low Dodge, followed by the Massachusetts Peace Society. The groups merged into the American Peace Society, which held weekly meetings and produced literature that was spread as far as Gibraltar and Malta describing the horrors of war and advocating pacifism on Christian grounds.[8] The London Peace Society, also known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was formed by philanthropist William Allen in 1816 to promote permanent, universal peace. During the 1840s, British women formed 15-to-20 person "Olive Leaf Circles" to discuss and promote pacifist ideas.[9]

The London Peace Society's influence began to grow during the mid-nineteenth century. Under

By the 1850s, these movements were becoming well organized in the major countries of Europe and North America, reaching middle-class activists beyond the range of the earlier religious connections.[12]

Support decreased during the resurgence of militarism during the

In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the novelist Baroness Bertha von Suttner (1843–1914) after 1889 became a leading figure in the peace movement with the publication of her pacifist novel, Die Waffen nieder! (Lay Down Your Arms!). The book was published in 37 editions and translated into 12 languages. She helped organize the German Peace Society and became known internationally as the editor of the international pacifist journal Die Waffen nieder! In 1905 she became the first woman to win a Nobel Peace Prize.[14]

Mahatma Gandhi and nonviolent resistance

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) was one of the 20th century's most influential spokesmen for peace and non-violence, and Gandhism is his body of ideas and principles Gandhi promoted. One of its most important concepts is nonviolent resistance. According to M. M. Sankhdher, Gandhism is not a systematic position in metaphysics or political philosophy but a political creed, an economic doctrine, a religious outlook, a moral precept, and a humanitarian worldview. An effort not to systematize wisdom but to transform society, it is based on faith in the goodness of human nature.[15]

Gandhi was strongly influenced by the pacifism of

Gandhi was the first person to apply the principle of nonviolence on a large scale.[18] The concepts of nonviolence (ahimsa) and nonresistance have a long history in Indian religious and philosophical thought, and have had a number of revivals in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Jewish and Christian contexts. Gandhi explained his philosophy and way of life in his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Some of his remarks were widely quoted, such as "There are many causes that I am prepared to die for, but no causes that I am prepared to kill for."[19]

Gandhi later realized that a high level of nonviolence required great faith and courage, which not everyone possessed. He advised that everyone need not strictly adhere to nonviolence, especially if it was a cover for cowardice: "Where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence."[20][21]

Gandhi came under political fire for his criticism of those who attempted to achieve independence through violence. He responded, "There was a time when people listened to me because I showed them how to give fight to the British without arms when they had no arms ... but today I am told that my non-violence can be of no avail against the Hindu–Moslem riots; therefore, people should arm themselves for self-defense."[22]

Gandhi's views were criticized in Britain during the Battle of Britain. He told the British people in 1940, "I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions ... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves man, woman, and child to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them."[23]

World War I

Although the onset of the

In 1915, the

Henry Ford

Peace promotion was a major activity of American automaker and philanthropist Henry Ford (1863-1947). He set up a $1 million fund to promote peace, and published numerous antiwar articles and ads in hundreds of newspapers.[28][29][30]

According to biographer Steven Watts, Ford's status as a leading industrialist gave him a worldview that warfare was wasteful folly that retarded long-term economic growth. The losing side in the war typically suffered heavy damage. Small business were especially hurt, for it takes years to recuperate. He argued in many newspaper articles that capitalism would discourage warfare because, “If every man who manufactures an article would make the very best he can in the very best way at the very lowest possible price the world would be kept out of war, for commercialists would not have to search for outside markets which the other fellow covets.” Ford admitted that munitions makers enjoyed wars, but he argued the typical capitalist wanted to avoid wars to concentrate on manufacturing and selling what people wanted, hiring good workers, and generating steady long-term profits.[31]

In late 1915, Ford sponsored and funded a Peace Ship to Europe, to help end the raging World War. He brought 170 peace activists; Jane Addams was a key supporter who became too ill to join him. Ford talked to President Woodrow Wilson about the mission but had no government support. His group met with peace activists in neutral Sweden and the Netherlands. A target of much ridicule, Ford left the ship as soon as it reached Sweden.[32][33]

Interwar period

Organizations

A popular slogan was "

The immense loss of life during the First World War for what became known as futile reasons caused a sea-change in public attitudes to militarism. Organizations formed at this time included War Resisters' International,[35] the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, the No More War Movement, and the Peace Pledge Union (PPU). The League of Nations convened several disarmament conferences, such as the Geneva Conference. They achieved very little. However the Washington conference of 1921-1922 did successfully limit naval armaments of the major powers during the 1920s.[36]

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom helped convince the U.S. Senate to launch an influential investigation by the Nye Committee to the effect that the munitions industry and Wall Street financiers had promoted American entry into World War I to cover their financial investments. The immediate result was a series of laws imposing neutrality on American business if other countries went to war.[37]

Novels and films

Pacifism and revulsion to war were popular sentiments in 1920s Britain. A number of novels and poems about the futility of war and the slaughter of youth by old fools were published, including Death of a Hero by Richard Aldington, Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front and Beverley Nichols' Cry Havoc! A 1933 University of Oxford debate on the proposed motion that "one must fight for King and country" reflected the changed mood when the motion was defeated. Dick Sheppard established the Peace Pledge Union in 1934, renouncing war and aggression. The idea of collective security was also popular; instead of outright pacifism, the public generally exhibited a determination to stand up to aggression with economic sanctions and multilateral negotiations.[38]

Spanish Civil War

The

World War II

At the beginning of

Pacifists in Nazi Germany were treated harshly. German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky[44] and Norwegian pacifist Olaf Kullmann[45] (who remained active during the German occupation) died in concentration camps. Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter was executed in 1943 for refusing to serve in the Wehrmacht.[46]

Anti-nuclear movement

Peace movements emerged in Japan, combining in 1954 to form the Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear-weapons tests was widespread, and an "estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[47]

In the United Kingdom, the

The CND advocated the unconditional renunciation of the use, production, or dependence upon nuclear weapons by Britain, and the creation of a general disarmament convention. Although the country was progressing towards de-nuclearization, the CND declared that Britain should halt the flight of nuclear-armed planes, end nuclear testing, stop using missile bases, and not provide nuclear weapons to any other country.

The first

Popular opposition to nuclear weapons produced a Labour Party resolution for unilateral nuclear disarmament at the 1960 party conference,[52] but the resolution was overturned the following year[53] and did not appear on later agendas. The experience disillusioned many anti-nuclear protesters who had previously put their hopes in the Labour Party.

Two years after the CND's formation, president Bertrand Russell resigned to form the Committee of 100; the committee planned to conduct sit-down demonstrations in central London and at nuclear bases around the UK. Russell said that the demonstrations were necessary because the press had become indifferent to the CND and large-scale, direct action could force the government to change its policy.[54] One hundred prominent people, many in the arts, attached their names to the organization. Large numbers of demonstrators were essential to their strategy but police violence, the arrest and imprisonment of demonstrators, and preemptive arrests for conspiracy diminished support. Although several prominent people took part in sit-down demonstrations (including Russell, whose imprisonment at age 89 was widely reported), many of the 100 signatories were inactive.[55]

Since the Committee of 100 had a non-hierarchical structure and no formal membership, many local groups assumed the name. Although this helped civil disobedience to spread, it produced policy confusion; as the 1960s progressed, a number of Committee of 100 groups protested against social issues not directly related to war and peace.

In 1961, at the height of the

In 1958, Linus Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with a petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear weapons testing. The 1961 Baby Tooth Survey, co-founded by Dr. Louise Reiss, indicated that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows which ate contaminated grass.[58][59][60] Public pressure and the research results then led to a moratorium on above ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy, Nikita Khrushchev, and Harold Macmillan.[61] On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize: "Linus Carl Pauling, who ever since 1946 has campaigned ceaselessly, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts."[62][63] Pauling founded the International League of Humanists in 1974; he was president of the scientific advisory board of the World Union for Protection of Life, and a signatory of the Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement.

On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's

Forty thousand anti-nuclear and anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York on May 1, 2005, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[71] The protest was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades.[72] In Britain, there were many protests against the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system with newer missiles. The largest of the protests had 100,000 participants and, according to polls, 59 percent of the public opposed the move.[72]

The

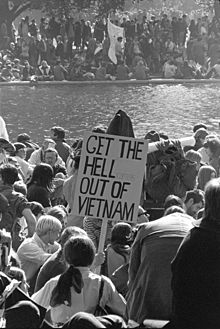

Vietnam War protests

The anti-Vietnam War peace movement began during the 1960s in the United States, opposing U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Some within the movement advocated a unilateral withdrawal of American forces from South Vietnam.

Opposition to the Vietnam War aimed to unite groups opposed to U.S. anti-communism, imperialism, capitalism and colonialism, such as New Left groups and the Catholic Worker Movement. Others, such as Stephen Spiro, opposed the war based on the just war theory.

In 1965, the movement began to gain national prominence. Provocative actions by police and protesters turned anti-war demonstrations in Chicago at the 1968 Democratic National Convention into a riot. News reports of American military abuses such as the 1968 My Lai massacre brought attention (and support) to the anti-war movement, which continued to expand for the duration of the conflict.

High-profile opposition to the Vietnam war turned to street protests in an effort to turn U.S. political opinion against the war. The protests gained momentum from the

Europe in 1980s

A very large peace movement emerged in East and West Europe in the 1980s, primarily in opposition to American plans to fight the Cold War by stationing nuclear missiles in Europe.[75][76][77] Moscow supported the movement behind the scenes, but did not control it.[78][79] However, communist-sponsored peace movements in Eastern Europe metamorphosed into genuine peace movements calling not only for détente, but for democracy. According to Hania Fedorowicz, they played an important role in East Germany and other countries in resurrecting civil society, and helped instigate the successful 1989 peaceful revolutions in Eastern Europe.[80]

Peace movements by country

Canada

Canadian pacifist Agnes Macphail was the first woman elected to the House of Commons. Macphail objected to the Royal Military College of Canada in 1931 on pacifist grounds.[81] Macphail was also the first female Canadian delegate to the League of Nations, where she worked with the World Disarmament Committee. Despite her pacifism, she voted for Canada to enter World War II. The Canadian Peace Congress (1949–1990) was a leading organizer of the Canadian peace movement, particularly under the leadership of James Gareth Endicott (its president until 1971).[82]

For over a century Canada has had a diverse peace movement, with coalitions and networks in many cities, towns, and regions. The largest national umbrella organization is the Canadian Peace Alliance, whose 140 member groups include large city-based coalitions, small grassroots groups, national and local unions and faith, environmental and student groups for a combined membership of over four million. The alliance and its member groups have led opposition to the war on terror. The CPA opposed Canada's participation in the war in Afghanistan and Canadian complicity in what it views as misguided and destructive United States foreign policy.[83] Canada has also been home to a growing movement of Palestinian solidarity, marked by an increasing number of grassroots Jewish groups opposed to Israeli policies.[84]

Germany

Germany developed a strong pacifist movement in the late 19th century; it was suppressed during the Nazi era. After 1945 in East Germany it was controlled by the communist government.[85]

During the Cold War (1947–1989), the West German peace movement concentrated on the abolition of nuclear technology (particularly nuclear weapons) from West Germany and Europe. Most activists criticized both the United States and the Soviet Union. According to conservative critics, the movement had been infiltrated by Stasi agents.[86]

After 1989, the ideal of peace was espoused by

Israel

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

Israeli–Palestinian and Arab–Israeli conflicts have existed since the dawn of Zionism, particularly since the 1948 formation of the state of Israel and the 1967 Six-Day War. The mainstream peace movement in Israel is Peace Now (Shalom Akhshav), which tends to support the Labour Party or Meretz.

Peace Now was founded in the aftermath of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat's visit to Jerusalem, when it was felt that an opportunity for peace could be missed. Prime Minister Menachem Begin acknowledged that on the eve of his departure for the Camp David summit with Sadat and US President Jimmy Carter, Peace Now rallies in Tel Aviv (which drew a crowd of 100,000, the largest peace rally in Israel to date) played a major role in his decision to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and dismantle Israeli settlements there. Peace Now supported Begin for a time and hailed him as a peacemaker, but turned against him when the Sinai withdrawal was accompanied by an accelerated campaign of land confiscation and settlement-building on the West Bank.

Peace Now advocates a negotiated peace with the Palestinians. This was originally worded vaguely, with no definition of "the Palestinians" and who represents them. Peace Now was slow to join the dialogue with the PLO begun by groups such as the Israeli Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace and the Hadash coalition; only in 1988 did the group accept that the PLO is the body regarded by the Palestinians as their representative.

During the

After the 2014 Gaza War, a group of Israeli women founded Women Wage Peace with the goal of reaching a "bilaterally acceptable" peace agreement between Israel and Palestine.[87] The movement has worked to build connections with Palestinians, reaching out to women and men from a variety of religions and political backgrounds.[88] Its activities have included a collective hunger strike outside Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's residence[89] and a protest march from Northern Israel to Jerusalem.[88] In May 2017, Women Wage Peace had over 20,000 members and supporters.[90]

United Kingdom

From 1934 the Peace Pledge Union gained many adherents to its pledge "I renounce war and will never support or sanction another." Its support diminished considerably with the outbreak of war in 1939, but it remained the focus of pacifism in the post-war years.

After World War II, peace efforts in the United Kingdom were initially focused on the dissolution of the British Empire and the rejection of imperialism by the United States and the Soviet Union. The anti-nuclear movement sought to opt out of the Cold War, rejecting "Britain's Little Independent Nuclear Deterrent" (BLIND) on the grounds that it contradicted mutual assured destruction.

Although the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, (VSC, led by Tariq Ali) led several large demonstrations against the Vietnam War in 1967 and 1968, the first anti-Vietnam demonstration was at the American Embassy in London in 1965.[91] In 1976, the Lucas Plan (led by Mike Cooley) sought to transform production at Lucas Aerospace from arms to socially-useful production.

The peace movement was later associated with peace camps, as the Labour Party moved to the center under Prime Minister Tony Blair. By early 2003, the peace and anti-war movements (grouped as the Stop the War Coalition) were powerful enough to cause several of Blair's cabinet to resign and hundreds of Labour MPs to vote against their government. Blair's motion to support the U.S. plan to invade Iraq continued due to support from the Conservative Party. Protests against the Iraq War were particularly vocal in Britain. Polls suggested that without UN Security Council approval, the UK public was opposed to involvement. Over two million people protested in Hyde Park; the previous largest demonstration in the UK had about 600,000 participants.

The primary function of the National Peace Council was to provide opportunities for consultation and joint activities by its affiliated members, to help inform public opinion on the issues of the day, and to convey to the government the views of its members. The NPC disbanded in 2000 and was replaced the following year by the "Network for Peace", set up to continue the NPC's networking role.[92]

United States

Near the end of the Cold War, U.S. peace activists focused on slowing the nuclear arms race in the hope of reducing the possibility of nuclear war between the U.S. and the USSR. As the

In response to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, President George H. W. Bush began preparing for war in the region. Peace activists were starting to gain traction with popular rallies, especially on the West Coast, just before the Gulf War began in February 1991. The ground war ended in less than a week with a lopsided Allied victory, and a media-incited wave of patriotic sentiment washed over the nascent protest movement.

During the 1990s, peacemaker priorities included seeking a solution to the Israeli–Palestinian impasse, belated efforts at humanitarian assistance to war-torn regions such as Bosnia and Rwanda, and aid to post-war Iraq. American peace activists brought medicine into Iraq in defiance of U.S. law, resulting in heavy fines and imprisonment for some. The principal groups involved included Voices in the Wilderness and the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Before and after the Iraq War began in 2003, a concerted protest effort was formed in the United States. A series of protests across the globe was held on February 15, 2003, with events in about 800 cities. The following month, just before the American- and British-led invasion of Iraq, "The World Says No to War" protest attracted as many as 500,000 protestors to cities across the U.S. After the war ended, many protest organizations persisted because of the American military and corporate presence in Iraq.

American activist groups, including

The

Although President Barack Obama continued the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, attendance at peace marches "declined precipitously".[96] Social scientists Michael T. Heaney and Fabio Rojas noted that from 2007 to 2009, "the largest antiwar rallies shrank from hundreds of thousands of people to thousands, and then to only hundreds."[97]

See also

- American Friends Service Committee

- Capitalist peace

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Global peace system

- Imagine Piano Peace Project

- International Fellowship of Reconciliation

- Service Civil International

- International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- International security

- List of anti-war organizations

- Make love, not war

- Opposition to World War I

- Opposition to World War II

- Opposition to the Iraq War

- Opposition to the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

- Pacifism

- Peace and conflict studies

- Peace Organisation of Australia

- Peace Pledge Union, in UK

- Peace symbols

- Peace Ship

- Peaceworker

- Soviet influence on the peace movement

- Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- World peace

References

- ^ Michael Howard, The Invention of Peace: Reflections on War and International Order (2001) pp1-6.

- ^ Daniel Francis Callahan. "Peace of God". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Eric Roberts. "Quaker Traditions of Pacifism and Nonviolence". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ^ Hinsley, F. H. Power and the Pursuit of Peace: Theory and Practice in the History of Relations between States (1967) pp. 46-61.

- ^ Hinsley, pp.62-80.

- ^ F. H. Hinsley, Power and the Pursuit of Peace: Theory and Practice in the History of Relations between States (1967) pp 13–80.

- ISBN 9780198226741. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ Pacifism to 1914: an overview by Peter Brock. Toronto, Thistle Printing, 1994. (pp. 38-9).

- ISBN 0-86068-688-4(pp. 14-5).

- ISBN 9781139471855. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ André Durand (October 31, 1996). "Gustave Moynier and the peace societies". International Review of the Red Cross (314). International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- JSTOR 1898869.

- JSTOR 3827086.

- ^ Richard R. Laurence, "Bertha von Suttner and the peace movement in Austria to World War I". Austrian History Yearbook 23 (1992): 181-201.

- ^ M. M. Sankhdher, "Gandhism: A Political Interpretation", Gandhi Marg (1972) pp. 68–74

- ISBN 0-941910-03-2. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-271-00414-3. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ISBN 81-219-0346-7.

- ^ James Geary, Geary's Guide to the World's Great Aphorists (2007) p. 87

- ISBN 9780887063312.

- ^ Faisal Devji, The Impossible Indian: Gandhi and the Temptation of Violence (Harvard University Press; 2012)

- ^ reprinted in Louis Fischer, ed. The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas 2002 (reprint edition) p. 311.

- ISBN 9780199728725.

- ^ Herman, 56-7

- ^ F. H. Hinsley, Power and the Pursuit of Peace: Theory and Practice in the History of Relations between States (1967) pp 269–308.

- ^ Pacifism vs. Patriotism in Women's Organizations in the 1920s Archived 2002-11-08 at archive.today.

- ^ Chatfield, Charles, “Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy” 2002 Archived 2007-10-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ David Lanier Lewis, The public image of Henry Ford: An American folk hero and his company (Wayne State University Press, 1976) p. 78–92.

- ^ Allan Nevins and Frank Ernest Hill, Ford: Expansion and Challenge, 1915–1933 (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1957) pp 26–54.

- ^ "Examining the American peace movement prior to World War I". April 6, 2017.

- ^ Steven Watts, The people's tycoon: Henry Ford and the American century (Vintage, 2009), pp 236-237.

- ^ Watts, The people's tycoon: Henry Ford and the American century (2005) pp 226-40.

- ISBN 1299115713

- ^ Engelbrecht, H.C.; Hanighen, F.C. (1934). Merchants of Death. Mises Institute. (free to download as pdf or epub)

- ISBN 0-8156-3028-X, p.18.

- ^ Neil Earle, "Public Opinion for Peace: Tactics of Peace Activists at the Washington Conference on Naval Armament (1921-1922)." Journal of Church and State 40#1 (1998), pp. 149–69, online.

- ^ John Edward Wiltz, "The Nye Committee Revisited." Historian 23.2 (1961): 211-233 online.

- University of Wellington.

- ^ "War and the Iliad". The New York Review of books. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ Lynd, Staughton. Nonviolence in America: a documentary history, Bobbs-Merrill, 1966, (PPS. 271–296).

- ISBN 0-517-00393-7

- ^ ISBN 0-06-011701-X

- ^ Brock and Young, p. 220.

- ^ Brock and Young, p.99.

- ^ Brock and Socknat, pp. 402-3.

- ISBN 0-87243-141-X.

- ^ a b Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 96-97.

- ISBN 0-85031-487-9

- ^ "Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND)". Spartacus-Educational.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ "The history of CND -".

- Guardian Unlimited. 1958-04-05.

- ^ April Carter, Direct Action and Liberal Democracy, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973, p. 64.

- ^ Robert McKenzie, "Power in the Labour Party: The Issue of 'Intra-Party Democracy'", in Dennis Kavanagh, The Politics of the Labour Party, Routledge, 2013.

- ^ , Bertrand Russell, "Civil Disobedience", New Statesman, 17 February 1961

- ^ Frank E. Myers, "Civil Disobedience and Organizational Change: The British Committee of 100", Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 86, No. 1. (Mar., 1971), pp. 92–112

- ^ Woo, Elaine (January 30, 2011). "Dagmar Wilson dies at 94; organizer of women's disarmament protesters". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (January 23, 2011). "Dagmar Wilson, Anti-Nuclear Leader, Dies at 94". The New York Times.

- ^ Louise Zibold Reiss (November 24, 1961). "Strontium-90 Absorption by Deciduous Teeth: Analysis of teeth provides a practicable method of monitoring strontium-90 uptake by human populations" (PDF). Science. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- ^ Thomas Hager (November 29, 2007). "Strontium-90". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Thomas Hager (November 29, 2007). "The Right to Petition". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 98.

- ^ Linus Pauling (October 10, 1963). "Notes by Linus Pauling. October 10, 1963". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.

- ^ Jonathan Schell. The Spirit of June 12 Archived 2019-05-12 at the Wayback Machine The Nation, July 2, 2007.

- ^ "1982 - a million people march in New York City". Archived from the original on June 16, 2010.

- ^ Harvey Klehr. Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today Transaction Publishers, 1988, p. 150.

- ^ 1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested Miami Herald, June 21, 1983.

- ^ Hundreds of Marchers Hit Washington in Finale of Nationwaide Peace March Gainesville Sun, November 16, 1986.

- ^ Robert Lindsey. 438 "Protesters are Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site", The New York Times, February 6, 1987.

- ^ "493 Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site", The New York Times, April 20, 1992.

- ^ Anti-Nuke Protests in New York Archived 2010-10-31 at the Wayback Machine Fox News, May 2, 2005.

- ^ a b Lawrence S. Wittner. A rebirth of the anti-nuclear weapons movement? Portents of an anti-nuclear upsurge Archived 2010-06-19 at the Wayback Machine Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 7 December 2007.

- ^ "International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament". February 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-01-04.

- ^ A-bomb survivors join 25,000-strong anti-nuclear march through New York Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine Mainichi Daily News, May 4, 2010.

- ^ Martin Baumeister, and Benjamin Ziemann, "Introduction: Peace Movements in Southern Europe during the 1970s and 1980s." Journal of Contemporary History 56.3 (2021): 563-578.

- ^ Thomas Rochon, Mobilizing for Peace: The Antinuclear Movements in Western Europe (Princeton UP 1988.

- ^ Belinda Davis, "Europe Is a Peaceful Woman, America Is a War-Mongering Man? The 1980s Peace Movement in NATO-Allied Europe." European History–Gender History,” Themenportal Europäische Geschichte (2009) online.

- ^ Cyril E. Black, et al. A History of Europe since World War II (2nd ed. 2000) pp 159–161.

- ^ David Cortright, "Assessing peace movement effectiveness in the 1980s." Peace & Change 16.1 (1991): 46-63.

- ^ Hania Fedorowicz, "East-West Dialogue: Detente from Below" Peace Research Reviews (1991) 11#6 pp 1-80.

- ^ Preston, Canada's RMC: A History of the Royal Military College (University of Toronto Press, 1969)

- ^ Victor Huard, "The Canadian Peace Congress and the Challenge to Postwar Consensus, 1948–1953." Peace & Change 19.1 (1994): 25-49.

- ^ Joanne Dufay and Sheena Lambert, "Women in the Canadian Peace Alliance." Canadian Woman Studies 9.1 (1988).

- ^ Gary Moffatt, A history of the peace movement in Canada (Grape Vine Press, 1982).

- ^ Benjamin Ziemann, "German Pacifism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries." Neue Politische Literatur 2015.3 (2015): 415-437. online

- ^ Wilfried von Bredow, "The Peace Movement in the Federal Republic of Germany", Armed Forces & Society (1982) 9#1 pp 33-48

- ^ "Mission Statement | Women Wage Peace". Women Wage Peace. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ a b "These Israeli women marched from the Lebanese border to Jerusalem. Here's why". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Operation Protective Fast: Striving for peace between Israelis and Palestinians". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "A women's movement that is trying to bring peace to Israel | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Comment Magazine. (Communist) "The University of Alabama-Bounds Law Library". Archived from the original on 2012-08-28. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- ^ "About us". Network for Peace.

- ^ Colman McCarthy (February 8, 2009). "From Lafayette Square Lookout, He Made His War Protest Permanent". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The Oracles of Pennsylvania Avenue - Al Jazeera World - Al Jazeera English". Archived from the original on 2012-07-10.

- ^ "For a Middle East free of all Weapons of Mass Destruction". Campaign Against Sanctions and Military Intervention in Iran. 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ Brad Plumer (August 29, 2013). "How Obama demobilized the antiwar movement". The Washington Post.

- ^ Gene Healy (December 14, 2015). "How Partisanship Killed the Anti-War Movement". Cato Institute.

Further reading

- Bajaj, Monisha, ed. Encyclopedia of peace education (IAP, 2008).

- Bussey, Gertrude, and Margaret Tims. Pioneers for Peace: Women's International League for Peace and Freedom 1915-1965 (Oxford: Alden Press, 1980).

- Carter, April. Peace movements: International protest and world politics since 1945 (Routledge, 2014).

- Cortright, David. Peace: A history of movements and ideas (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- Costin, Lela B. "Feminism, pacifism, internationalism and the 1915 International Congress of Women." Women's Studies International Forum 5#3-4 (1982).

- Durand, André. "Gustave Moynier and the peace societies". In: International Review of the Red Cross (1996), no. 314, p. 532–550

- Giugni, Marco. Social protest and policy change: Ecology, antinuclear, and peace movements in comparative perspective (Rowman & Littlefield, 2004).

- Hinsley, F. H. Power and the Pursuit of Peace: Theory and Practice in the History of Relations between States (Cambridge UP, 1967) online.

- Howard, Michael. The Invention of Peace: Reflections on War and International Order (2001) excerpt

- Jakopovich, Daniel. Revolutionary Peacemaking: Writings for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence (Democratic Thought, 2019). ISBN 978-953-55134-2-1

- Kulnazarova, Aigul, and Vesselin Popovski, eds. The Palgrave handbook of global approaches to peace (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

- Kurtz, Lester R., and Jennifer Turpin, eds. Encyclopedia of violence, peace, and conflict (Academic Press, 1999).

- Marullo, Sam, and ISBN 0-8135-1561-0

- Moorehead, Caroline. Troublesome People: The Warriors of Pacifism (Bethesda, MD: Adler & Adler, 1987).

- Schlabach, Gerald W. "Christian Peace Theology and Nonviolence toward the Truth: Internal Critique amid Interfaith Dialogue." Journal of Ecumenical Studies 53.4 (2018): 541-568. online

- Vellacott, Jo. "A place for pacifism and transnationalism in feminist theory: the early work of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom." Women History Review 2.1 (1993): 23-56. online

- Weitz, Eric. A World Divided: The Global Struggle for Human Rights in the Age of Nation States (Princeton University Press, 2019). online reviews

National studies

- Bennett, Scott H. Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915–45 (Syracuse UP, 2003).

- Brown, Heloise. 'The truest form of patriotism': Pacifist feminism in Britain, 1870-1902 (Manchester University Press, 2003).

- Ceadel, Martin. The origins of war prevention: the British peace movement and international relations, 1730-1854 (Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Ceadel, Martin. Semi-detached idealists: the British peace movement and international relations, 1854-1945 (Oxford University Press, 2000) online.

- Ceadel, Martin. "The First British Referendum: The Peace Ballot, 1934-5." English Historical Review 95.377 (1980): 810-839. online

- Chatfield, Charles, ed. Peace Movements in America (New York: Schocken Books, 1973). ISBN 0-8052-0386-9

- Chatfield, Charles. with Robert Kleidman. The American Peace Movement: Ideals and Activism (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1992). ISBN 0-8057-3852-5

- Chickering, Roger. Imperial Germany and a World Without War: The Peace Movement and German Society, 1892-1914 (Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Clinton, Michael. "Coming to Terms with 'Pacifism': The French Case, 1901–1918." Peace & Change 26.1 (2001): 1-30.

- Cooper, Sandi E. "Pacifism in France, 1889-1914: international peace as a human right." French historical studies (1991): 359-386. online

- Davis, Richard. "The British Peace Movement in the Interwar Years." Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique. French Journal of British Studies 22.XXII-3 (2017). online

- Davy, Jennifer Anne. "Pacifist thought and gender ideology in the political biographies of women peace activists in Germany, 1899-1970: introduction." Journal of Women's History 13.3 (2001): 34-45.

- Eastman, Carolyn, "Fight Like a Man: Gender and Rhetoric in the Early Nineteenth-Century American Peace Movement", American Nineteenth Century History 10 (Sept. 2009), 247–71.

- Fontanel, Jacques. "An underdeveloped peace movement: The case of France." Journal of Peace Research 23.2 (1986): 175-182.

- Hall, Mitchell K., ed. Opposition to War: An Encyclopedia of US Peace and Antiwar Movements (2 vol. ABC-CLIO, 2018).

- Howlett, Charles F., and Glen Zeitzer. The American Peace Movement: History and Historiography (American Historical Association, 1985).

- Kimball, Jeffrey. "The Influence of Ideology on Interpretive Disagreement: A Report on a Survey of Diplomatic, Military and Peace Historians on the Causes of 20th Century U. S. Wars", History Teacher 17#3 (1984) pp. 355-384 DOI: 10.2307/493146 online

- Laity, Paul. The British Peace Movement 1870-1914 (Clarendon Press, 2002).

- Locke, Elsie. Peace People: A History of Peace Activities in New Zealand (Christchurch, NZ: Hazard Press, 1992). ISBN 0-908790-20-1

- Lukowitz, David C. "British pacifists and appeasement: the Peace Pledge Union." Journal of Contemporary History 9.1 (1974): 115-127.

- Oppenheimer, Andrew. "West German Pacifism and the Ambivalence of Human Solidarity, 1945–1968." Peace & Change 29.3‐4 (2004): 353-389. online

- Peace III, Roger C. A Just and Lasting Peace: The U.S. Peace Movement from the Cold War to Desert Storm (Chicago: The Noble Press, 1991). ISBN 0-9622683-8-0

- Pugh, Michael. "Pacifism and politics in Britain, 1931–1935." Historical Journal 23.3 (1980): 641-656. online

- Puri, Rashmi-Sudha. Gandhi on War & Peace (1986); focus on India.

- Ritchie, J. M. "Germany–a peace-loving nation? A Pacifist Tradition in German Literature." Oxford German Studies 11.1 (1980): 76-102.

- Saunders, Malcolm. "The origins and early years of the Melbourne Peace Society 1899/1914." Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 79.1-2 (1993): 96-114.

- Socknat, Thomas P. "Canada's Liberal Pacifists and the Great War." Journal of Canadian Studies 18.4 (1984): 30-44.

- Steger, Manfred B. Gandhi's dilemma: Nonviolent principles and nationalist power (St. Martin's Press, 2000) online review.

- Strong-Boag, Veronica. "Peace-making women: Canada 1919–1939." in Women and Peace (Routledge, 2019) pp. 170-191.

- Talini, Giulio. "Saint-Pierre, British pacifism and the quest for perpetual peace (1693–1748)." History of European Ideas 46.8 (2020): 1165-1182.

- Vaïsse, Maurice. "A certain idea of peace in France from 1945 to the present day." French History 18.3 (2004): 331-337.

- Wittner, Lawrence S. Rebels Against War: The American Peace Movement, 1933–1983 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984). ISBN 0-87722-342-4

- Ziemann, Benjamin. "German Pacifism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries." Neue Politische Literatur 2015.3 (2015): 415-437 online.

Primary sources

- Lynd, Staughton, and Alice Lynd, eds. Nonviolence in America: A documentary history (3rd ed. Orbis Books, 2018).

- Stellato, Jesse, ed. Not in Our Name: American Antiwar Speeches, 1846 to the Present (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012). 287 pp

External links

- Nonviolent Action Network – Nonviolent Action Network Database of 300 nonviolent methods