Apolipoprotein B

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 2: 21 – 21.04 Mb | Chr 12: 8.03 – 8.07 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the APOB gene. It is commonly used to detect risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.[5][6]

Function

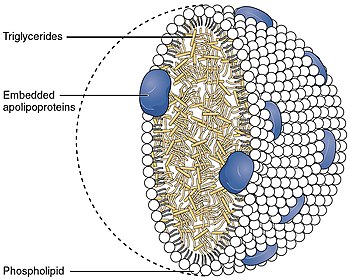

Apolipoprotein B is the primary

Through mechanisms only partially understood, high levels of ApoB, especially associated with the higher LDL particle concentrations, are the primary driver of

Genetic disorders

High levels of ApoB are related to heart disease.

Mutations in gene APOB100 can also cause familial hypercholesterolemia,[12] a hereditary (autosomal dominant) form of metabolic disorder hypercholesterolemia.

Mouse studies

Mice have been used as

Molecular biology

The

As a result of the RNA editing, ApoB48 and ApoB100 share a common N-terminal sequence, but ApoB48 lacks ApoB100's C-terminal LDL receptor binding region. In fact, ApoB48 is so-called because it constitutes 48% of the sequence for ApoB100.

ApoB 48 is a unique protein to chylomicrons from the small intestine. After most of the lipids in the chylomicron have been absorbed, ApoB48 returns to the liver as part of the chylomicron remnant, where it is endocytosed and degraded.

Clinical significance

Benefits

Role in innate immune system

Very low-density lipoproteins and low-density lipoproteins interfere with the quorum sensing system that upregulates genes required for invasive Staphylococcus aureus infection. The mechanism of antagonism entails binding ApoB, to a S. aureus autoinducer pheromone, preventing signaling through its receptor. Mice deficient in ApoB are more susceptible to invasive bacterial infection.[16]

Adverse effects

Role in insulin resistance

Overproduction of apolipoprotein B can result in lipid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance in the liver.[17]

Role in lipoproteins and atherosclerosis

ApoB100 is found in

). Importantly, there is one ApoB100 molecule per hepatic-derived lipoprotein. Hence, using that fact, one can quantify the number of lipoprotein particles by noting the total ApoB100 concentration in the circulation. Since there is one and only one ApoB100 per particle, the number of particles is reflected by the ApoB100 concentration. The same technique can be applied to individual lipoprotein classes (e.g. LDL) and thereby enable one to count them as well.It is well established that ApoB100 levels are associated with

One way to explain the above is to consider that large numbers of lipoprotein particles, and, in particular, large numbers of LDL particles, lead to competition at the ApoB100 receptor (i.e. LDL receptor) of peripheral cells. Since such competition will prolong the residence time of LDL particles in the circulation, it may lead to greater opportunity for them to undergo

The INTERHEART study found that the ApoB100 / ApoA1 ratio is more effective at predicting heart attack risk, in patients who had had an acute myocardial infarction, than either the ApoB100 or ApoA1 measure alone.

A Mediterranean diet is recommended as a means of lowering Apolipoprotein B.[25]

Interactions

ApoB has been shown to

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

Regulation

The expression of APOB is regulated by cis-regulatory elements in the APOB 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR.[31]

RNA editing

The

. ApoB100 and ApoB48 are encoded by the same gene, however, the differences in the translated proteins are not due to alternative splicing but are due to the tissue-specific RNA editing event. ApoB mRNA editing was the first example of editing observed in vertebrates.[32] Editing of ApoB mRNA occurs in all placental mammals.[33] Editing occurs post transcriptionally as the nascent polynucleotides do not contain edited nucleosides.[34]Type

C to U editing of ApoB mRNA requires an editing complex or

Location

Despite being a 14,000 residue long transcript, a single cytidine is targeted for editing. Within the ApoB mRNA a sequence consisting of 26 nucleotides necessary for editing is found. This is known as the editing motif. These nucleotides (6662–6687) were determined to be essential by site specific mutagenesis experiments.[45] An 11 nucleotide portion of this sequence 4–5 nucleotides downstream from the editing site is an important region known as the mooring sequence.[46] A region called the spacer element is found 2–8 nucleotides between the edited nucleoside and this mooring sequence.[47] There is also a regulatory sequence 3′ to the editing site. The active site of ApoBEC-1, the catalytic component of the editing holoenzyme is thought to bind to an AU rich region of the mooring sequence with the aid of ACF in binding the complex to the mRNA.[48] The edited cytidine residue is located at nucleotide 6666 located in exon 26 of the gene. Editing at this site results in a codon change from a Glutamine codon (CAA) to an inframe stop codon (UAA).[32] Computer modelling has detected for editing to occur, the edited Cytidine is located in a loop.[46] The selection of the edited cytidine is also highly dependent on this secondary structure of the surrounding RNA. There are also some indications that this loop region is formed between the mooring sequence and the 3′ regulatory region of the ApoB mRNA.[49] The predicted secondary structure formed by ApoB mRNA is thought to allow for contact between the residue to be edited and the active site of APOBEC1 as well as for binding of ACF and other auxiliary factors associated with the editosome.

Regulation

Editing of ApoB mRNA in humans is tissue regulated, with ApoB48 being the main ApoB protein of the small intestine in humans. It occurs in lesser amounts in the colon, kidney and stomach along with the non edited version.[50] Editing is also developmentally regulated with the non edited version only being translated early in development but the edited form increases during development in the tissues where editing can occur.[51][52] Editing levels of ApoB mRNA have been shown to vary in response to changes in diet. exposure to alcohol and hormone levels.[53][54][55]

Conservation

ApoB mRNA editing also occurs in mice, and rats. In contrast to humans editing occurs in liver in mice and rats up to a frequency of 65%.[56] It has not been observed in birds or lesser species.[57]

Consequences

Structure

Editing results in a codon change creating an in-frame stop codon leading to translation of a truncated protein, ApoB48. This stop codon results in the translation of a protein that lacks the carboxyl terminus which contains the protein's LDLR binding domain. The full protein ApoB100 which has nearly 4500 amino acids is present in VLDL and LDL. Since many parts of ApoB100 are in an amphipathic condition, the structure of some of its domains is dependent on underlying lipid conditions. However, it is known to have the same overall folding in LDL having five main domains. Recently the first structure of LDL at human body temperature in native condition has been found using cryo-electron microscopy at a resolution of 16 Angstrom.[58] The overall folding of ApoB-100 has been confirmed and some heterogeneity in the local structure of its domains have been mapped.[citation needed]

Function

Editing is restricted to those transcripts expressed in the small intestine. This shorter version of the protein has a function specific to the small intestine. The main function of the full length liver expressed ApoB100 is as a ligand for activation of the LDL-R. However, editing results in a protein lacking this LDL-R binding region of the protein. This alters the function of the protein and the shorter ApoB48 protein as specific functions relative to the small intestine.

ApoB48 is identical to the amino-terminal 48% of ApoB100.

See also

- Apolipoprotein A1

- ACAT2

- Cardiovascular disease

- Lipid metabolism

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000084674 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020609 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- PMID 36216435.

- PMID 34677405.

- PMID 21784371.

- PMID 21803958.

- PMID 15198959.

- PMID 2725600.

- ^ "MTTP microsomal triglyceride transfer protein [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- PMID 27919345.

- PMID 8662599.

- PMID 7878058.

- ^ PMID 3759943.

- PMID 19064256.

- S2CID 205869807.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Apolipoprotein B100

- PMID 19657464.

- S2CID 23464159.

- PMID 36216435.

- S2CID 26567691.

- S2CID 213180689.

- PMID 17170368.

- PMID 27821191.

- PMID 23484137.

- ^ PMID 12397072.

- ^ PMID 9694898.

- PMID 15472124.

- PMID 17938300.

- PMID 15157107.

- ^ S2CID 37938313.

- PMID 10373583.

- PMID 1939106.

- ^ "APOBEC1 Gene - GeneCards | ABEC1 Protein | ABEC1 Antibody". Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- PMID 9466941.

- ^ "A1CF Gene - GeneCards | A1CF Protein | A1CF Antibody". Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- PMID 12896982.

- PMID 11577082.

- PMID 11134005.

- S2CID 25911416.

- PMID 11584023.

- PMID 14559896.

- PMID 8577721.

- PMID 2760026.

- ^ PMID 1885564.

- PMID 8246950.

- PMID 1649450.

- PMID 9822632.

- PMID 2243107.

- PMID 2373694.

- PMID 3460091.

- PMID 2229075.

- PMID 8576634.

- PMID 9084497.

- S2CID 314984.

- PMID 2341807.

- PMID 21573056.

- S2CID 536926.

Further reading

- Mahley RW, Innerarity TL, Rall SC, Weisgraber KH (1985). "Plasma lipoproteins: apolipoprotein structure and function". J. Lipid Res. 25 (12): 1277–1294. PMID 6099394.

- Itakura H, Matsumoto A (1995). "[Apolipoprotein B]". Nippon Rinsho. 52 (12): 3113–3118. PMID 7853698.

- Chumakova OS, Zateĭshchikov DA, Sidorenko BA (2006). "[Apolipoprotein B: structure, function, gene polymorphism, and relation to atherosclerosis]". Kardiologiia. 45 (6): 43–55. PMID 16007035.

- Ye J (2007). "Reliance of host cholesterol metabolic pathways for the life cycle of hepatitis C virus". PLOS Pathog. 3 (8): e108. PMID 17784784.

External links

- Database of RNA editing (DARNED).

- Applied Research on Apolipoprotein-B

- Human APOB genome location and APOB gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.