Statin

| Statin | |

|---|---|

C10AA | |

| Biological target | HMG-CoA reductase |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D019161 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Statins (or HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) are a class of medications that lower cholesterol. They are prescribed typically to people who are at high risk of cardiovascular disease.[1]

Side effects of statins include

They act by inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which plays a central role in the production of cholesterol. High cholesterol levels have been associated with cardiovascular disease.[8]

There are

Patient compliance with statin usage is problematic despite robust evidence of the benefits.[14][15]

Medical uses

Statins are usually used to lower blood cholesterol levels and reduce risk for illnesses related to atherosclerosis, with a varying degree of effect depending on underlying

If there is an underlying history of cardiovascular disease, it has a significant impact on the effects of statin. This can be used to divide medication usage into broad categories of primary and secondary prevention.[22]

Primary prevention

For the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, the

Most evidence suggests that statins are also effective in preventing heart disease in those with

The

Secondary prevention

Statins are effective in decreasing mortality in people with pre-existing

No studies have examined the effect of statins on cognition in patients with prior stroke. However, two large studies (HPS and PROSPER) that included people with vascular diseases reported that simvastatin and pravastatin did not impact cognition.[41]

Statins have been studied for improving operative outcomes in cardiac and vascular surgery.[42] Mortality and adverse cardiovascular events were reduced in statin groups.[43]

Older adults who receive statin therapy at time of discharge from the hospital after an

Statin product offerings - comparative effectiveness

All statins appear effective regardless of potency or degree of cholesterol reduction.[26][46][47] Simvastatin and pravastatin appear to have a reduced incidence of side-effects.[5][48][49]

Women and children

According to the 2015 Cochrane systematic review, atorvastatin showed greater cholesterol-lowering effect in women than in men compared to rosuvastatin.[50]

In children, statins are effective at reducing cholesterol levels in those with familial hypercholesterolemia.[51] Their long term safety is, however, unclear.[51][52] Some recommend that if lifestyle changes are not enough statins should be started at 8 years old.[53]

Familial hypercholesterolemia

Statins may be less effective in reducing LDL cholesterol in people with familial hypercholesterolemia, especially those with

Contrast-induced nephropathy

A 2014 meta-analysis found that statins could reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy by 53% in people undergoing coronary angiography/percutaneous interventions. The effect was found to be stronger among those with preexisting kidney dysfunction or diabetes mellitus.[58]

Chronic kidney disease

The risk of cardiovascular disease is similar in people with chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease and statins are often suggested.[16] There is some evidence that appropriate use of statin medications in people with chronic kidney disease who do not require dialysis may reduce mortality and the incidence of major cardiac events by up to 20% and are not that likely to increase the risk of stroke or kidney failure.[16]

Asthma

Statins have been identified as having a possible adjunct role in the treatment of asthma through anti-inflammatory pathways.[59] There is low quality evidence for the use of statins in treating asthma, however further research is required to determine the effectiveness and safety of this therapy in those with asthma.[59]

Adverse effects

| Condition | Commonly recommended statins | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney transplantation recipients taking ciclosporin | Pravastatin or fluvastatin | Drug interactions are possible, but studies have not shown that these statins increase exposure to ciclosporin.[61] |

| HIV-positive people taking protease inhibitors | Atorvastatin, pravastatin or fluvastatin | Negative interactions are more likely with other choices.[62] |

| Persons taking gemfibrozil, a non-statin lipid-lowering drug | Atorvastatin | Combining gemfibrozil and a statin increases risk of rhabdomyolysis and subsequently kidney failure[63][64] |

| Persons taking the anticoagulant warfarin | Any statin | The statin use may require that the warfarin dose be changed, as some statins increase the effect of warfarin.[65] |

The most important adverse side effects are muscle problems, an increased risk of

Other possible adverse effects include

Cognitive effects

Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that the available evidence does not support an association between statin use and cognitive decline.[77][78][79][80][81] A 2010 meta-review of medical trials involving over 65,000 people concluded that Statins decreased the risk of dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and even improved cognitive impairment in some cases.[82][needs update] Additionally, both the Patient-Centered Research into Outcomes Stroke Patients Prefer and Effectiveness Research (PROSPER) study[83] and the Health Protection Study (HPS) demonstrated that simvastatin and pravastatin did not affect cognition for patients with risk factors for, or a history of, vascular diseases.[84]

There are reports of reversible cognitive impairment with statins.[85] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) package insert on statins includes a warning about the potential for non-serious and reversible cognitive side effects with the medication (memory loss, confusion).[86]

Muscles

In observational studies 10–15% of people who take statins experience

Muscle pain and other symptoms often cause patients to stop taking a statin.[88] This is known as statin intolerance. A 2021 double-blind multiple crossover randomized controlled trial (RCT) in statin-intolerant patients found that adverse effects, including muscle pain, were similar between atorvastatin and placebo.[89] A smaller double-blind RCT obtained similar results.[90] The results of these studies help explain why statin symptom rates in observational studies are so much higher than in double-blind RCTs and support the notion that the difference results from the nocebo effect; that the symptoms are caused by expectations of harm.[91]

Media reporting on statins is often negative, and patient leaflets inform patients that rare but potentially serious muscle problems can occur during statin treatment. These create expectations of harm. Nocebo symptoms are real and bothersome and are a major barrier to treatment. Because of this, many people stop taking statins,[92] which have been proven in numerous large-scale RCTs to reduce heart attacks, stroke, and deaths[93] – as long as people continue to take them.

Serious muscle problems such as

Records exist of over 250,000 people treated from 1998 to 2001 with the statin drugs atorvastatin, cerivastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin.[100] The incidence of rhabdomyolysis was 0.44 per 10,000 patients treated with statins other than cerivastatin. However, the risk was over 10-fold greater if cerivastatin was used, or if the standard statins (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, or simvastatin) were combined with a fibrate (fenofibrate or gemfibrozil) treatment. Cerivastatin was withdrawn by its manufacturer in 2001.[101]

Some researchers have suggested hydrophilic statins, such as fluvastatin, rosuvastatin, and pravastatin, are less toxic than lipophilic statins, such as atorvastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin, but other studies have not found a connection.[102] Lovastatin induces the expression of gene atrogin-1, which is believed to be responsible in promoting muscle fiber damage.[102] Tendon rupture does not appear to occur.[103]

Diabetes

The relationship between statin use and risk of developing

Cancer

Several meta-analyses have found no increased risk of cancer, and some meta-analyses have found a reduced risk.

Drug interactions

Combining any statin with a

Consumption of

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) notified healthcare professionals of updates to the prescribing information concerning interactions between protease inhibitors and certain statin drugs. Protease inhibitors and statins taken together may increase the blood levels of statins and increase the risk for muscle injury (myopathy). The most serious form of myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, can damage the kidneys and lead to kidney failure, which can be fatal.[132]

Osteoporosis and fractures

Studies have found that the use of statins may protect against getting osteoporosis and fractures or may induce osteoporosis and fractures.[133][134][135][136] A cross-sectional retrospective analysis of the entire Austrian population found that the risk of getting osteoporosis is dependent on the dose used.[137]

Mechanism of action

Statins act by

Inhibiting cholesterol synthesis

By inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, statins block the pathway for synthesizing cholesterol in the liver. This is significant because most circulating cholesterol comes from internal manufacture rather than the diet. When the liver can no longer produce cholesterol, levels of cholesterol in the blood will fall. Cholesterol synthesis appears to occur mostly at night,[140] so statins with short half-lives are usually taken at night to maximize their effect. Studies have shown greater LDL and total cholesterol reductions in the short-acting simvastatin taken at night rather than the morning,[141][142] but have shown no difference in the long-acting atorvastatin.[143]

Increasing LDL uptake

In rabbits,

Decreasing of specific protein prenylation

Statins, by inhibiting the HMG CoA reductase pathway, inhibit downstream synthesis of isoprenoids, such as farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. Inhibition of protein prenylation for proteins such as RhoA (and subsequent inhibition of Rho-associated protein kinase) may be involved, at least partially, in the improvement of endothelial function, modulation of immune function, and other pleiotropic cardiovascular benefits of statins,[145][146][147][148][149][150] as well as in the fact that a number of other drugs that lower LDL have not shown the same cardiovascular risk benefits in studies as statins,[151] and may also account for some of the benefits seen in cancer reduction with statins.[152] In addition, the inhibitory effect on protein prenylation may also be involved in a number of unwanted side effects associated with statins, including muscle pain (myopathy)[153] and elevated blood sugar (diabetes).[154]

Other effects

As noted above, statins exhibit action beyond lipid-lowering activity in the prevention of atherosclerosis through so-called "pleiotropic effects of statins".[148] The pleiotropic effects of statins remain controversial.[155] The ASTEROID trial showed direct ultrasound evidence of atheroma regression during statin therapy.[156] Researchers hypothesize that statins prevent cardiovascular disease via four proposed mechanisms (all subjects of a large body of biomedical research):[155]

- Improve endothelial function

- Modulate inflammatory responses

- Maintain plaque stability

- Prevent blood clot formation

In 2008, the JUPITER trial showed statins provided benefit in those who had no history of high cholesterol or heart disease, but only in those with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels, an indicator for inflammation.[157] The study has been criticized due to perceived flaws in the study design,[158][159][160] although Paul M. Ridker, lead investigator of the JUPITER trial, has responded to these criticisms at length.[161]

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

As the target of statins, the HMG-CoA reductase, is highly similar between

Available forms

The statins are divided into two groups:

| Statin | Image | Brand name | Derivation | Metabolism[63] | Half-life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin |  |

Arkas, Ator, Atoris, Lipitor, Torvast, Totalip | Synthetic | CYP3A4 | 14–19 hours.[165] |

| Cerivastatin |  |

Baycol, Lipobay (withdrawn from the market in August 2001 due to risk of serious rhabdomyolysis) | Synthetic | various CYP3A isoforms[166] | |

| Fluvastatin |  |

Lescol, Lescol XL, Lipaxan, Primesin | Synthetic | CYP2C9 | 1–3 hours.[165] |

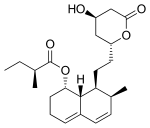

| Lovastatin |  |

Altocor, Altoprev, Mevacor | Naturally occurring, fermentation-derived compound. It is found in oyster mushrooms and red yeast rice |

CYP3A4 | 1–3 hours.[165] |

| Mevastatin |  |

Compactin | Naturally occurring compound found in red yeast rice | CYP3A4 | |

| Pitavastatin |  |

Alipza, Livalo, Livazo, Pitava, Zypitamag | Synthetic | CYP2C9 and CYP2C8 (minimally) | |

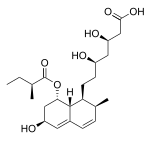

| Pravastatin |  |

Aplactin, Lipostat, Prasterol, Pravachol, Pravaselect, Sanaprav, Selectin, Selektine, Vasticor | Fermentation-derived (a fermentation product of bacterium Nocardia autotrophica) | Non-CYP[167] | 1–3 hours.[165] |

| Rosuvastatin |  |

Colcardiol, Colfri, Crativ, Crestor, Dilivas, Exorta, Koleros, Lipidover, Miastina, Provisacor, Rosastin, Simestat, Staros | Synthetic | CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 | 14–19 hours.[165] |

| Simvastatin |  |

Alpheus, Corvatas, Krustat, Lipenil, Lipex, Liponorm, Medipo, Omistat, Rosim, Setorilin, Simbatrix, Sincol, Sinvacor, Sinvalip, Sivastin, Sinvat, Vastgen, Vastin, Xipocol, Zocor | Fermentation-derived (simvastatin is a synthetic derivate of a fermentation product of Aspergillus terreus) | CYP3A4 | 1–3 hours.[165] |

Atorvastatin + amlodipine |

Caduet, Envacar | Combination therapy: statin + calcium antagonist | |||

| Atorvastatin + perindopril + amlodipine | Lipertance, Triveram[168][169][170] | Combination therapy: statin + ACE inhibitor + calcium antagonist | |||

| Lovastatin + niacin extended-release | Advicor, Mevacor | Combination therapy | |||

| Rosuvastatin + ezetimibe | Cholecomb, Delipid Plus, Росулип плюс, Rosulip, Rosumibe, Viazet[171][172][173][174] | Combination therapy: statin + cholesterol absorption inhibitor | |||

| Simvastatin + ezetimibe | Goltor, Inegy, Staticol, Vytorin, Zestan, Zevistat | Combination therapy: statin + cholesterol absorption inhibitor | |||

| Simvastatin + niacin extended-release | Simcor, Simcora | Combination therapy |

LDL-lowering potency varies between agents. Cerivastatin is the most potent (withdrawn from the market in August 2001 due to risk of serious rhabdomyolysis), followed by (in order of decreasing potency) rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and fluvastatin.[175] The relative potency of pitavastatin has not yet been fully established, but preliminary studies indicate a potency similar to rosuvastatin.[176]

Some types of statins are naturally occurring, and can be found in such foods as

| % LDL reduction (approx.) | Atorvastatin | Fluvastatin | Lovastatin | Pravastatin | Rosuvastatin | Simvastatin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–20% | – | 20 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | – | 5 mg |

| 20–30% | – | 40 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | – | 10 mg |

| 30–40% | 10 mg | 80 mg | 40 mg | 40 mg | 5 mg | 20 mg |

| 40–45% | 20 mg | – | 80 mg | 80 mg | 5–10 mg | 40 mg |

| 46–50% | 40 mg | – | – | – | 10–20 mg | 80 mg[a] |

| 50–55% | 80 mg | – | – | – | 20 mg | – |

| 56–60% | – | – | – | – | 40 mg | – |

| Starting dose | ||||||

| Starting dose | 10–20 mg | 20 mg | 10–20 mg | 40 mg | 10 mg; 5 mg if hypothyroid, >65 yo, Asian | 20 mg |

| If higher LDL reduction goal | 40 mg if >45% | 40 mg if >25% | 20 mg if >20% | – | 20 mg if LDL >190 mg/dL (4.87 mmol/L) | 40 mg if >45% |

| Optimal timing | Anytime | Evening | With evening meals | Anytime | Anytime | Evening |

- ^ 80 mg dose no longer recommended due to increased risk of rhabdomyolysis.

History

The role of cholesterol in the development of cardiovascular disease was elucidated in the second half of the 20th century.

In 1971,

A British group isolated the same compound from Penicillium brevicompactum, named it

In the 1990s, as a result of public campaigns, people in the United States became familiar with their cholesterol numbers and the difference between HDL and LDL cholesterol, and various pharmaceutical companies began producing their own statins, such as pravastatin (Pravachol), manufactured by Sankyo and

Though he did not profit from his original discovery, Endo was awarded the 2006

As of 2016[update] misleading claims exaggerating the adverse effects of statins had received widespread media coverage, with a consequent negative impact to public health.[35] Controversy over the effectiveness of statins in the medical literature was amplified in popular media in the early 2010s, leading an estimated 200,000 people in the UK to stop using statins over a six-month period to mid 2016, according to the authors of a study funded by the British Heart Foundation. They estimated that there could be up to 2,000 extra heart attacks or strokes over the following 10 years as a consequence.[195] An unintended effect of the academic statin controversy has been the spread of scientifically questionable alternative therapies. Cardiologist Steven Nissen at Cleveland Clinic commented "We are losing the battle for the hearts and minds of our patients to Web sites..."[196] promoting unproven medical therapies. Harriet Hall sees a spectrum of "statin denialism" ranging from pseudoscientific claims to the understatement of benefits and overstatement of side effects, all of which is contrary to the scientific evidence.[197]

Several statins have been approved as generic drugs in the United States:

- Lovastatin (Mevacor) in December 2001[198][199][200]

- Pravastatin (Pravachol) in April 2006[201][202][203]

- Simvastatin (Zocor) in June 2006[204][205][206]

- Atorvastatin (Lipitor) in November 2011[207][208][209][210]

- Fluvastatin (Lescol) in April 2012[211][212]

- Pitavastatin (Livalo) and rosuvastatin (Crestor) in 2016[213][214]

- Ezetimibe/simvastatin (Vytorin) and ezetimibe/atorvastatin (Liptruzet) in 2017[215]

Research

Clinical studies have been conducted on the use of statins in

A modelling study in the UK found that people aged 70 and older who take statins live longer in good health than those who do not, regardless of whether they have cardiovascular disease.[225][226]

References

- ^ "Cholesterol Drugs". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- PMID 30715135.

- National Library of Medicine.

- ^ PMID 23440795.

- ^ S2CID 18340552.

- ^ S2CID 207487287.

- ^ "Should you be worried about severe muscle pain from statins?". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- S2CID 54293528.

- ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ PMID 24276813.

- ^ PMID 12602122.

- ^ "2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Pfizer. 23 April 2009. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2013.

- PMID 23225173.

- PMID 33842201.

- ^ PMID 38018702.

- PMID 35285850.

- ^ National Cholesterol Education Program (2001). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Executive Summary. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. p. 40. NIH Publication No. 01-3670.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (2010). NICE clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification (PDF). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2010.

- S2CID 35330627.

- S2CID 32861954.

- ^ PMID 30423393.

- ^ S2CID 205075217.

- ^ "ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator". www.cvriskcalculator.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- PMID 30712900.

- ^ PMID 21989464.

- PMID 22300691.

- PMID 18793814.

- PMID 20585067.

- PMID 20377811.

- ^ "Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification at www.nice.org.uk". 18 July 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- PMID 24222016.

- PMID 25285604.

- PMID 22115524.

- ^ S2CID 4641278.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (March 2010) [May 2008]. "Lipid modification – Cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease – Quick reference guide" (PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- PMID 12829554.

- S2CID 539314.

- S2CID 45663315.

- PMID 23817482.

- PMID 28095900.

- PMID 25186819.

- PMID 25498191.

- PMID 29057688.

- PMID 28242176.

- PMID 22935195.

- ^ "Assessing Severity of Statin Side Effects: Fact Versus Fiction". American College of Cardiology. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- PMID 31194369, retrieved 11 November 2023

- PMID 32411300.

- PMID 25760954.

- ^ PMID 31696945.

- S2CID 22846175.

- S2CID 21141894.

- ^ PMID 24481802.

- PMID 26546829.

- PMID 12813012.

- S2CID 8075552.

- S2CID 28251228.

- ^ PMID 32668027.

- ^ table adapted from the following source, but check individual references for technical explanations

- Consumer Reports, Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2013), "Evaluating statin drugs to treat High Cholesterol and Heart Disease: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF), Best Buy Drugs, Consumer Reports, p. 9, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2017, retrieved 27 March 2013

- S2CID 46971444.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Interactions between certain HIV or hepatitis C drugs and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs can increase the risk of muscle injury". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ PMID 15198967.

- S2CID 43757439.

- S2CID 205948651.

- S2CID 6247572.

- PMID 24641882.

- PMID 30666914.

- PMID 33330853.

- ^ PMID 19159124.

- S2CID 46535820.

- S2CID 42422361.

- S2CID 206902546.

- PMID 16490577.

- ^ PMID 21963058.

- S2CID 21064267.

- PMID 24095248.

- PMID 24267801.

- S2CID 207536770.

- S2CID 1990708.

- PMID 27440840.

- PMID 20585067.

- S2CID 11252336.

- PMID 28095900.

- PMID 25347692.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- PMID 28391891.

- S2CID 34832961.

- PMID 33627334.

- S2CID 226971988.

- S2CID 211046068.

- S2CID 219730531.

- PMID 21067804.

- PMID 30580575.

- ^ Rull R, Henderson R (20 January 2015). "Rhabdomyolysis and Other Causes of Myoglobinuria". Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- PMID 24799748.

- PMID 23452285.

- S2CID 3825396.

- PMID 18650507.

- ^ PMID 15572716.

- PMID 26721703.

- ^ PMID 17992259.

- S2CID 4652858.

- S2CID 11544414.

- PMID 27838722.

- ^ PMID 28797470.

- S2CID 52953760.

- PMID 21693744.

- PMID 22231607.

- S2CID 140506916.

- PMID 22902202.

- PMID 22101921.

- PMID 17662392.

- PMID 16391219.

- S2CID 42869773.

- PMID 23357487.

- S2CID 17931279.

- S2CID 16584300.

- PMID 23599253.

- S2CID 37195287.

- S2CID 22078921.

- PMID 23049713.

- PMID 23468972.

- PMID 23879311.

- S2CID 35249884.

- S2CID 13171692.

- S2CID 9030195.

- from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Katherine Zeratsky, R.D., L.D., Mayo clinic: article on interference between grapefruit and medication Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 1 May 2017

- PMID 10994829.

- from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Statins and HIV or Hepatitis C Drugs: Drug Safety Communication – Interaction Increases Risk of Muscle Injury". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- PMID 29723231.

- PMID 27258488.

- S2CID 4723680.

- PMID 30423123.

- PMID 31558481.

- S2CID 37686043.

- ^ PMID 1464741.

- PMID 7200504.

- PMID 2065035.

- PMID 14525878.

- S2CID 13586550.

- PMID 3464957.

- S2CID 46985044.

- PMID 16639429.

- PMID 17266583.

- ^ PMID 18834985.

- S2CID 1975524.

- PMID 23919640.

- ^ "Questions Remain in Cholesterol Research". MedPageToday. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- PMID 22529099.

- PMID 24835295.

- PMID 18053094.

- ^ PMID 15822172.

- PMID 16533939.

- PMID 18997196.

- PMID 21267417.

- S2CID 32142669.

- PMID 21046291.

- PMID 21029837.

- S2CID 73412833.

- PMID 26559904.

- PMID 26066650.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4160-5469-6.

The elimination half-life of the statins varies from 1 to 3 hours for lovastatin, simvastatin, pravastatin, and fluvastatin, to 14 to 19 hours for atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (see Table 22-1). The longer the half-life of the statin, the longer the inhibition of reductase and thus a greater reduction in LDL cholesterol. However, the impact of inhibiting cholesterol synthesis persists even with statins that have a relatively short half-life. This is due to their ability to reduce blood levels of lipoproteins, which have a half-life of approximately 2 to 3 days. Because of this, all statins may be dosed once daily. The preferable time of administration is in the evening just before the peak in cholesterol synthesis.

- PMID 9172950.

- PMID 9929499. Archived from the originalon 26 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Triveram" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Triveram (2)" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Riclassificazione del medicinale per uso umano 'Triveram', ai sensi dell'articolo 8, comma 10, della legge 24 dicembre 1993, n. 537. (Determina n. DG/1422/2019). (19A06231)". GU Serie Generale n.238 (in Italian). 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Cholecomb" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Cholecomb (2)" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Rosumibe" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Rosumibe (2)" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- PMID 12646338.

- S2CID 221814440.

- PMID 17302963.

- PMID 22149736.

- ^ Fang J (31 October 2019). "Patent expires today on pharmaceutical superstar Lipitor". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Sandoz launches authorized fluvastatin generic in US". GaBI Online. 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Teva Announces Final Approval of Lovastatin Tablets". Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. (Press release). 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "FDA OKs Generic Version of Pravachol". WebMD. 25 April 2006. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Generic Crestor Wins Approval, Dealing a Blow to AstraZeneca". The New York Times. 21 July 2016. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Wilson D (6 March 2011). "Drug Firms Face Billions in Losses as Patents End". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 November 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Berenson A (23 June 2006). "Merck Loses Protection for Patent on Zocor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- PMID 25815993.

- ISBN 978-0-12-373979-7.

- PMID 20467214.

- PMID 945291.

- PMID 29085751.

- PMID 32859023.

- S2CID 5965882.

- ^ Lane B (8 May 2012). "National Inventors Hall of Fame Honors 2012 Inductees". Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Landers P (9 January 2006). "How One Scientist Intrigued by Molds Found First Statin". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Boseley S (8 September 2016). "Statins prevent 80,000 heart attacks and strokes a year in UK, study finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Husten L (24 July 2017). "Nissen Calls Statin Denialism A Deadly Internet-Driven Cult". CardioBrief. Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Hall H (2017). "Statin Denialism". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 41, no. 3. pp. 40–43. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "First-Time Generics – December 2001". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Lovastatin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "ANDA Approval Reports - First-Time Generics - December 2001". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "First-Time Generics – April 2006". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Pravastatin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "ANDA Approval Reports - First-Time Generics - April 2006". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "First-Time Generics – June 2006". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Simvastatin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "ANDA Approval Reports - First-Time Generics - June 2006". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ DeNoon DJ (29 November 2011). "FAQ: Generic Lipitor". WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "First-Time Generic Drug Approvals – November 2011". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Atorvastatin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "ANDA Approval Reports - First-Time Generic Drug Approvals - November 2011". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "First-Time Generic Drug Approvals – April 2012". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "ANDA Approval Reports - First-Time Generic Drug Approvals - April 2012". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "ANDA (Generic) Drug Approvals in 2016". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 November 2018. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "FDA approves first generic Crestor". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "CDER 2017 First Generic Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- PMID 17640385.

- PMID 17494779.

- PMID 16788130.

- PMID 18413554.

- PMID 25037529.

- PMID 21334020.

- S2CID 3900946.

- S2CID 20522253.

- PMID 22161428.

- PMID 39256053.

- ^ "Older people who take statins live longer in better health". NIHR Evidence. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

External links

- Brody JE (16 April 2018). "Weighing the Pros and Cons of Statins". The New York Times.