Croatisation

Croatisation

Croatisation of Serbs

Religion

Croatisation of Italians in Dalmatia

Even with a predominant Croatian majority,

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor

His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

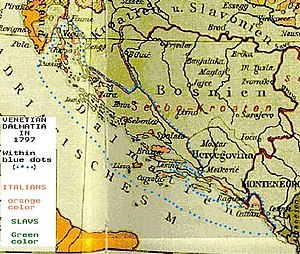

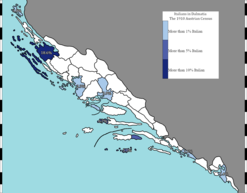

Dalmatia, especially its maritime cities, once had a substantial local Italian-speaking population (Dalmatian Italians), making up 33% of the total population of Dalmatia in 1803,[12][13] but this was reduced to 20% in 1816.[14] In Dalmatia there was a constant decline in the Italian population, in a context of repression that also took on violent connotations.[15] During this period, Austrians carried out an aggressive anti-Italian policy through a forced Slavization of Dalmatia.[16] According to Austrian censuses, the Italian speakers in Dalmatia formed 12.5% of the population in 1865,[17] but this was reduced to 2.8% in 1910.[18]

The Italian population in Dalmatia was concentrated in the major cities. In the city of Split in 1890 there were 1,969 Italians (12.5% of the population), in Zadar 7,423 (64.6%), in Šibenik 1,018 (14.5%) and in Dubrovnik 331 (4.6%).[19] In other Dalmatian localities, according to Austrian censuses, Italians experienced a sudden decrease: in the twenty years 1890-1910, in Rab they went from 225 to 151, in Vis from 352 to 92, in Pag from 787 to 23, completely disappearing in almost all the inland locations.

There are several reasons for the decrease of the Dalmatian Italian population following the rise of

- The conflict with the Austrian rulers caused by the Italian "Risorgimento".

- The emergence of Risorgimento), and the subsequent conflict of the two.

- The emigration of many Dalmatians toward the growing industrial regions of northern Italy before World War I and North and South America.

- Multi generational assimilation of anyone who married out of their social class and/or nationality – as perpetuated by similarities in education, religion, dual linguistic distribution, mainstream culture and economical output.

In 1909 the

During the

In 2001 about 500 Italians were counted in Dalmatia. In particular, according to the official Croatian census of 2011, there are 83 Italians in Split (equal to 0.05% of the total population), 16 in Šibenik (0.03%) and 27 in Dubrovnik (0.06%).[29] According to the official Croatian census of 2021, there are 63 Italians in Zadar (equal to 0.09% of the total population).[30]

Croatisation in Bosnia and Herzegovina

19th century

During the 19th century, with the emergence of ideologies and active political engagements on introduction of ethno-national identity and nationhood among

Meanwhile, contemporary scholars saw Croatisation as a long lasting process of influencing and changing historical memory, through various methods and strategies.[32] Dubravko Lovrenović, for instance, saw it as influencing a reception and interpretation of Bosnian medieval times, underlining its contemporary usage via revision and re-interpretation, in forms spanning from historical mythmaking by domestic and especially neighboring ethno-religious and nationalist elites, to identity and culture politics, often based on fringe science and public demagoguery of academic elite, with language and material heritage in its midst.[32]

Late 20th century

Following the establishment of the

, and Šunje.Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the official language Serbo-Croatian broke up into separate official languages and the process in relation to Croatian involved the Croatisation of its lexicon.[43]

Croatisation in the NDH

The Croatisation during Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was aimed primarily towards Serbs, and to a lesser degree, towards Jews and Roma. The Ustaše aim was a "pure Croatia" and the main target was the ethnic Serb population of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ministers of NDH announced the goals and strategies of the Ustaše in May 1941. The same statements and similar or related ones were also repeated in public speeches by single ministers, such as Mile Budak in Gospić and, a month later, by Mladen Lorković.[44]

- One third of the Serbs (in the Independent State of Croatia) were to be forcibly converted to Catholicism

- One third of the Serbs were to be expelled (ethnically cleansed)

- One third of the Serbs were to be killed

A Croatian Orthodox Church was established in order to try and pacify the state as well as to Croatisize the remaining Serb population once the Ustaše realized that the complete eradication of Serbs in the NDH was unattainable.[45]

Notable individuals who voluntarily Croatised

- Dimitrija Demeter, a playwright who was the author of the first modern Croatian drama, was from a Greek family.

- Vatroslav Lisinski, a composer, was originally named Ignaz Fuchs. His Croatian name is a literal translation.

- Bogoslav Šulek, a lexicographer and inventor of many Croatian scientific terms, was originally Bohuslav Šulek from Slovakia.

- Stanko Vraz, a poet and the first professional writer in Croatia, was originally Jakob Frass from Slovenia.

- August Šenoa, a Croatian novelist, poet and writer, is of Czech-Slovak descent. His parents never learned the Croatian language, even when they lived in Zagreb.

- Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger, a geologist, palaeontologist and archaeologist who discovered Krapina man[46] (Krapinski pračovjek), was of German descent. He added his second name, Gorjanović, to be adopted as a Croatian.

- Slavoljub Eduard Penkala was an inventor of Dutch/Polish origins. He added the name Slavoljub in order to Croatise.

- Lovro Monti, Croatian politician, mayor of Knin. One of the leaders of the Croatian national movement in Dalmatia, he was of Italian roots.

- Adolfo Veber Tkalčević -linguist of German descent

- Ivan Zajc (born Giovanni von Seitz) a music composer was of German descent

Other

Notable individuals, of Croatian origin, partially Magyarized through intermarriages and then Croatized again, include families:

- Keglević

- Pejačević(Pejasevich)

- Ladislav Pejačević

- Teodor Pejačević

- Dora Pejačević[47]

- George Martinuzzi

See also

- Cultural assimilation

- Anti-Croat Sentiment

- Bosniakisation

- Germanisation

- Italianization

- Magyarization

- Serbianisation

- Serbs of Croatia

- Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

- Dalmatian Italians

- Istrian Italians

- Forced assimilation

- Independent State of Croatia

- Ustaše

- Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia

- Greater Croatia

Notes

- ^ Z. Kudelić, Isusovačko izvješće o krajiškim nemirima 1658. i 1666. godine, Hrvatski institut za povijest, 2007, page 121

- S2CID 147078894.

- ^ Mileusnić, Slobodan (2007). "Spiritual genocide". www.intratext.com. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Horvat, Rudolf (1941). "Lika i Krbava" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Horvat, Zorislav (2018). "Samostan u Marči - ostatci ostataka".

- ^ "Manastir Marča – Mitropolija zagrebačko-ljubljanska" (in Serbian). Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Ikić, Niko (2019). "POVIJESNO-EKLEZIJALNI POGLED NA UNIJU U HRVATSKOJ IZ 1611. GODINE – RAST POTEŠKOĆA SJEDINJENJA, SMANJIVANJE CRKVENOG POVJERENJA". Faculty of Catholic Theology in Sarajevo.

- ^ "Trieste, Istria, Fiume e Dalmazia: una terra contesa" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

- ^ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971, vol. 2, p. 297. Citazione completa della fonte e traduzione in Luciano Monzali, Italiani di Dalmazia. Dal Risorgimento alla Grande Guerra, Le Lettere, Firenze 2004, p. 69.)

- ISBN 3484311347.

- ^ Bartoli, Matteo (1919). Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia (in Italian). Tipografia italo-orientale. p. 16.[ISBN unspecified]

- ISBN 9780416189407.

- ^ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 729

- ^ Raimondo Deranez (1919). Particolari del martirio della Dalmazia (in Italian). Ancona: Stabilimento Tipografico dell'Ordine.

- University of Padova. p. 396.[ISBN unspecified]

- ISSN 1330-0474.

- ^ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919" (in German). Archived from the original on 29 May 2013.

- ^ Guerrino Perselli, I censimenti della popolazione dell'Istria, con Fiume e Trieste e di alcune città della Dalmazia tra il 1850 e il 1936, Centro di Ricerche Storiche - Rovigno, Unione Italiana - Fiume, Università Popolare di Trieste, Trieste-Rovigno, 1993

- ISBN 9780416189407.

- ^ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 730

- ^ "Italiani di Dalmazia: 1919-1924" di Luciano Monzali

- ^ "Il primo esodo dei Dalmati: 1870, 1880 e 1920 - Secolo Trentino". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Društvo književnika Hrvatske, Bridge, Volume 1995, Numbers 9–10, Croatian literature series – Ministarstvo kulture, Croatian Writer's Association, 1989

- ISBN 978-0822392361. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ISBN 9781137308771.

- ISBN 0691086974.

- ISBN 9780044451945.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Marko Atilla Hoare, (2007), The history of Bosnia: from the Middle ages to the Present day, p.60

- ^ ISSN 2232-7770.

- ISSN 1849-1510. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Zemljopis i poviestnica Bosne. Internet Archive. 1851. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Zemljopis i poviestnica Bosne by Ivan Frano Jukić as Slavoljub Bošnjak, Zagreb, 1851, UDC 911.3(497.15)

- ^ Putpisi i istorisko-etnografski radovi by Ivan Frano Jukić as Slavoljub Bošnjak ASIN: B004TK99S6

- ^ "Kratka povjest kralja bosanskih". Dobra knjiga. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ "Predstavljanje: Kratka povjest kralja bosanskih". visoko.co.ba.vinet.ba. Archived from the original on 27 July 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ISBN 978-9958-688-68-3

- ^ "ICTY: Blaškić verdict – A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 c) The municipality of Kiseljak".

- ^ "ICTY: Blaškić verdict – A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 – b) The municipality of Busovača".

- ^ "ICTY: Blaškić verdict — A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993 – c) The municipality of Kiseljak".

the authorities created a radio station which broadcast nationalist propaganda

- .

- ISBN 978-88-430-4171-8, quoting from V. Novak, Sarajevo 1964 and Savez jevrejskih opstina FNR Jugoslavije, Beograd 1952

- ISBN 978-0-80477-924-1.

- ^ Krapina C Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dora Pejačević[4] ANCESTRY[5][6][7] Dora Pejačević Budapest, 1885 – Munich, 1923 (Roman Catholic) Father: Teodor Pejačević Našice, 1855 – Vienna, 1928) (Roman Catholic) Grandfather: Ladislav Pejačević [8][9] (Sopron, 18 – Našice, Veröce 1901 ) (Roman Catholic) Great-grandfather: Ferdinánd Pejačević[10] Sopron1800-Graz,(A) 1878(...) (Roman Catholic)(mother:Erdödy) Great-grandmother: Mária Döry de Jobaháza[11] Zomba, 1800 – Zalabér, Zala 1880) (Roman Catholic) mother: felsöbüki Julianna Nagy Grandmother: Gabriella Döry de Jobaháza? Zomba 1830 – Našice 1913) (Roman Catholic) Great-grandfather: Gábor Döry de Jóbaháza[12] (Pécs 1803, Szentgál 1871) (Roman Catholic) (mother: felsöbüki Júlia Nagy 1766-1828) Great-grandmother: Erzsébet Döry de Jóbaháza Zomba 1806 – Našice 18... (Roman Catholic) (f: Pál Döry/ m: Anna Krisztina Tallián, 1787 Ádánd-1809 Pécs) Mother: Elisabeth Vay Alsózsolca, Borsod 1860-1941 (Roman Catholic) Grandfather: báró vajai Béla Vay (1829 Alsózsolca, Borsod-1910 Alsózsolca- ) (Roman Catholic) Great-grandfather: báró vajai Lajos Vay 1803 Golop, Borsod – 1888 Vatta ) (Roman Catholic) Great-grandmother: gróf Erzsébet Teleki de Szék. (1812 Sáromberke, Maros-Torda – 1881 Budapest) (Roman Catholic) Grandmother: gróf széki Zsófia Teleki Gernyeszeg 1836, Maros-Torda, Transylvania, – , 1898) (Roman Catholic) Great-grandfather: gróf Domokos Teleki de Szék 1810 Marosvásárhely, Maros-Torda – 1876 Kolozsvár, Kolozs (Roman Catholic) Great-grandmother: Jozefa Bánffy de Losonc 1810 Déva, Hunyad (Roman Catholic)

External links

- http://www.tlfq.ulaval.ca/AXL/europe/croatiepolcroa.htm Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.serbianunity.net/culture/library/genocide/k3.htm

- http://www.aimpress.ch/dyn/trae/archive/data/199809/80930-018-trae-zag.htm

- http://www.southeasteurope.org/subpage.php?sub_site=2&id=16431&head=if&site=4 Archived 21 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.nouvelle-europe.eu/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=172&Itemid=

- http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=18696

- http://www.gimnazija.hr/?200_godina_gimnazije:OD_1897._DO_1921.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080328060638/http://www.hdpz.htnet.hr/broj186/jonjic2.htm