Political career of Fidel Castro

| History of Cuba |

|---|

|

| Governorate of Cuba (1511–1519) |

|

Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) |

|

|

| Captaincy General of Cuba (1607–1898) |

|

|

| US Military Government (1898–1902) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1902–1959) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1959–) |

|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Topical |

|

|

|

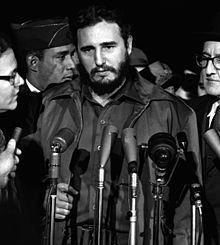

The political career of Fidel Castro saw Cuba undergo significant economic, political, and social changes. In the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro and an associated group of revolutionaries toppled the ruling government of Fulgencio Batista,[1] forcing Batista out of power on 1 January 1959. Castro, who had already been an important figure in Cuban society, went on to serve as Prime Minister from 1959 to 1976. He was also the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, the most senior position in the communist state, from 1961 to 2011. In 1976, Castro officially became President of the Council of State and President of the Council of Ministers. He retained the title until 2008, when the presidency was transferred to his brother, Raúl Castro. Fidel Castro remained the first secretary of the Communist Party until 2011.

Fidel Castro's government was officially atheist from 1962 until 1992.[2] Cuba attained international prominence under Fidel Castro's rule, for reasons including his staunch belief in communism, his criticisms of other international figures, and the economic and social changes that were initiated. Castro's Cuba became a key element within the Cold War struggle between the United States and its allies versus the Soviet Union and its allies. Castro's desire to take the offensive against capitalism and spread communist revolution ultimately led to the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias – FAR) fighting in Africa. His aim was to create many Vietnams, reasoning that American troops bogged down throughout the world could not fight any single insurgency effectively. An estimated 7,000–11,000 Cubans died in conflicts in Africa.[3]

Castro died of natural causes in late 2016 at Havana. Castro's ideas continue to be the primary foundation and manner in which the Cuban government functions to this day.

Premiership (1959–1976)

Consolidating rule (1959)

On February 16, 1959, Castro was sworn in as Prime Minister of Cuba, and accepted the position on the condition that the Prime Minister's powers be increased.[4] Between 15 and 26 April Castro visited the U.S. with a delegation of representatives, hired a public relations firm for a charm offensive, and presented himself as a "man of the people". U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower avoided meeting Castro; he was instead met by Vice President Richard Nixon, a man Castro instantly disliked.[5] Proceeding to Canada, Trinidad, Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, Castro attended an economic conference in Buenos Aires. He unsuccessfully proposed a $30 billion U.S.-funded "Marshall Plan" for the whole region of Latin America.[6]

After appointing himself president of the

Castro appointed himself president of the National Tourist Industry as well. He introduced unsuccessful measures to encourage

Although he refused to initially categorize his regime as '

"Until Castro, the U.S. was so overwhelmingly influential in Cuba that the American ambassador was the second most important man, sometimes even more important than the Cuban president."

—

Castro used radio and television to develop a "dialogue with the people", posing questions and making provocative statements.

Soviet support and U.S. opposition (1960)

By 1960, the

Relations between Cuba and the U.S. were further strained following the explosion of a French vessel, the

In September 1960, Castro flew to New York City for the

Castro returned to Cuba on 28 September. He feared a U.S.-backed coup and in 1959 spent $120 million on Soviet, French and Belgian weaponry. Intent on constructing the largest army in Latin America, by early 1960 the government had doubled the size of the Cuban armed forces.[35] Fearing counter-revolutionary elements in the army, the government created a People's Militia to arm citizens favorable to the revolution, and trained at least 50,000 supporters in combat techniques.[36] In September 1960, they created the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), a nationwide civilian organization which implemented neighborhood spying to weed out "counter-revolutionary" activities and could support the army in the case of invasion. They also organized health and education campaigns, and were a conduit for public complaints. Eventually, 80% of Cuba's population would be involved in the CDR.[37] Castro proclaimed the new administration a direct democracy, in which the Cuban populace could assemble en masse at demonstrations and express their democratic will. As a result, he rejected the need for elections, claiming that representative democratic systems served the interests of socio-economic elites.[38] In contrast, critics condemned the new regime as un-democratic. The U.S. Secretary of State Christian Herter announced that Cuba was adopting the Soviet model of communist rule, with a one-party state, government control of trade unions, suppression of civil liberties and the absence of freedom of speech and press.[39]

Castro's government emphasised social projects to improve Cuba's standard of living, often to the detriment of economic development.[40] Major emphasis was placed on education, and under the first 30 months of Castro's government, more classrooms were opened than in the previous 30 years. The Cuban primary education system offered a work-study program, with half of the time spent in the classroom, and the other half in a productive activity.[41] Health care was nationalized and expanded, with rural health centers and urban polyclinics opening up across the island, offering free medical aid. Universal vaccination against childhood diseases was implemented, and infant mortality rates were reduced dramatically.[40] A third aspect of the social programs was the construction of infrastructure; within the first six months of Castro's government, 600 miles of road had been built across the island, while $300 million was spent on water and sanitation schemes.[40] Over 800 houses were constructed every month in the early years of the administration in a measure to cut homelessness, while nurseries and day-care centers were opened for children and other centers opened for the disabled and elderly.[40]

Unemployment in Cuba fell significantly over the course of the 1960s and 70s, and a social security bank was founded in early 1959 to assist the unemployed.[42] Seasonal unemployment, previously endemic, was eradicated by overstaffing in the new state farms and migration to urban areas which freed up jobs in the countryside. Many migrants found jobs in new public works projects, the army, trade unions, and security roles.[43] General unemployment was also reduced through greater employment in social services and the bureaucracy, overstaffing in industry, the removal from the ranks of the jobseekers of the young and old through the expansion of education and social security, and the freeing up of jobs through mass emigration.[44] Economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago estimates that from a peak of 13.6% unemployed in 1959, unemployment consistently fell to a level of 1.3% by 1970.[45]

The Bay of Pigs Invasion and embracing socialism (1961–62)

"There was... no doubts about who the victors were. Cuba's stature in the world soared to new heights, and Fidel's role as the adored and revered leader among ordinary Cuban people received a renewed boost. His popularity was greater than ever. In his own mind he had done what generations of Cubans had only fantasized about: he had taken on the United States and won."

— Peter Bourne, Castro biographer, 1986[46]

In January 1961, Castro ordered Havana's U.S. Embassy to reduce its 300 staff, suspecting many to be spies. The U.S. responded by ending diplomatic relations, and increasing CIA funding for exiled dissidents; these militants began attacking ships trading with Cuba, and bombed factories, shops, and sugar mills.[47] Both Eisenhower and his successor John F. Kennedy supported a CIA plan to aid a dissident militia, the Democratic Revolutionary Front, to invade Cuba and overthrow Castro; the plan resulted in the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961. On 15 April, CIA-supplied B-26's bombed three Cuban military airfields; the U.S. announced that the perpetrators were defecting Cuban air force pilots, but Castro exposed these claims as false flag misinformation.[48] Fearing invasion, he ordered the arrest of between 20,000 and 100,000 suspected counter-revolutionaries,[49] publicly proclaiming that "What the imperialists cannot forgive us, is that we have made a Socialist revolution under their noses". This was his first announcement that the government was socialist.[50]

The CIA and Democratic Revolutionary Front had based a 1,400-strong army, Brigade 2506, in Nicaragua. At night, Brigade 2506 landed along Cuba's Bay of Pigs, and engaged in a firefight with a local revolutionary militia. Castro ordered Captain José Ramón Fernández to launch the counter-offensive, before taking personal control himself. After bombing the invader's ships and bringing in reinforcements, Castro forced the Brigade's surrender on 20 April.[51] He ordered the 1189 captured rebels to be interrogated by a panel of journalists on live television, personally taking over questioning on 25 April. 14 were put on trial for crimes allegedly committed before the revolution, while the others were returned to the U.S. in exchange for medicine and food valued at U.S. $25 million.[52] Castro's victory was a powerful symbol across Latin America, but it also increased internal opposition primarily among the middle-class Cubans who had been detained in the run-up to the invasion. Although most were freed within a few days, many left Cuba for the United States and established themselves in Florida.[53]

Consolidating "Socialist Cuba", Castro united the MR-26-7, Popular Socialist Party and Revolutionary Directorate into a governing party based on the Leninist principle of

The ORI began shaping Cuba using the Soviet model, persecuting political opponents and perceived

The Cuban Missile Crisis and furthering socialism (1962–1968)

Militarily weaker than

In February 1963, Castro received a personal letter from Khrushchev, inviting him to visit the USSR. Deeply touched, Castro arrived in April and stayed for five weeks. He visited 14 cities, addressed a Red Square rally and watched the May Day parade from the Kremlin, was awarded an honorary doctorate from Moscow State University and became the first foreigner to receive the Order of Lenin.[75][76] Castro returned to Cuba with new ideas; inspired by Soviet newspaper Pravda, he amalgamated Hoy and Revolución into a new daily, Granma,[77] and oversaw large investment into Cuban sport that resulted in an increased international sporting reputation.[78] The government agreed to temporarily permit emigration for anyone other than males aged between 15 and 26, thereby ridding the government of thousands of opponents.[79] In 1963 his mother died. This was the last time his private life was reported in Cuba's press.[80] In 1964, Castro returned to Moscow, officially to sign a new five-year sugar trade agreement, but also to discuss the ramifications of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[81] In October 1965, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations was officially renamed the "Cuban Communist Party" and published the membership of its Central Committee. Fidel Castro served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from 1965 to 2011.[79]

"The greatest threat presented by Castro's Cuba is as an example to other Latin American states which are beset by poverty, corruption, feudalism, and plutocratic exploitation ... his influence in Latin America might be overwhelming and irresistible if, with Soviet help, he could establish in Cuba a Communist utopia."

— Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964[82]

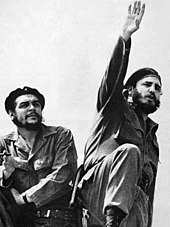

Despite Soviet misgivings, Castro continued calling for global revolution and the funding militant leftists. He supported Che Guevara's "Andean project", an unsuccessful plan to set up a guerrilla movement in the highlands of Bolivia, Peru and Argentina, and allowed revolutionary groups from across the world, from the

Castro's increasing role on the world stage strained his relationship with the Soviets, now under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev. Asserting Cuba's independence, Castro refused to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, declaring it a Soviet-U.S. attempt to dominate the Third World.[92] In turn, Soviet-loyalist Aníbal Escalante began organizing a government network of opposition to Castro, though in January 1968, he and his supporters were arrested for passing state secrets to Moscow.[93] Castro ultimately relented to Brezhnev's pressure to be obedient, and in August 1968 denounced the Prague Spring as led by a "fascist reactionary rabble" and praised the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[94][95][96] Influenced by China's Great Leap Forward, in 1968 Castro proclaimed a Great Revolutionary Offensive, closed all remaining privately owned shops and businesses and denounced their owners as capitalist counter-revolutionaries.[97]

Economic stagnation and Third World politics (1969–1974)

In January 1969, Castro publicly celebrated his administration's tenth anniversary in Revolution Square, using the occasion to ask the assembled crowds if they would tolerate reduced sugar rations, reflecting the country's economic problems.[97] The majority of the sugar crop was being sent to the USSR, but 1969's crop was heavily damaged by a hurricane; the government postponed the 1969–70 New Year holidays in order to lengthen the harvest. The military were drafted in, while Castro, and several other Cabinet ministers and foreign diplomats joined in.[98][99] The country nevertheless failed that year's sugar production quota. Castro publicly offered to resign, but assembled crowds denounced the idea.[100][101] Despite Cuba's economic problems, many of Castro's social reforms remained popular, with the population largely supportive of the "Achievements of the Revolution" in education, medical care and road construction, as well as the government's policy of "direct democracy".[40][101] Cuba turned to the Soviets for economic help, and from 1970 to 1972, Soviet economists re-planned and organized the Cuban economy, founding the Cuban-Soviet Commission of Economic, Scientific and Technical Collaboration, while Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin visited in 1971.[102] In July 1972, Cuba joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), an economic organization of socialist states, although this further limited Cuba's economy to agricultural production.[103]

In May 1970, Florida-based dissident group

In September 1973, he returned to

That year, Cuba experienced an economic boost, due primarily to the high international price of sugar, but also influenced by new trade credits with Canada, Argentina, and parts of Western Europe.

Presidency (1976–2008)

Foreign wars and NAM Presidency: (1975–1979)

"There is often talk of human rights, but it is also necessary to talk of the rights of humanity. Why should some people walk barefoot, so that others can travel in luxurious cars? Why should some live for thirty-five years, so that others can live for seventy years? Why should some be miserably poor, so that others can be hugely rich? I speak on behalf of the children in the world who do not have a piece of bread. I speak on the behalf of the sick who have no medicine, of those whose rights to life and human dignity have been denied."

— Fidel Castro's message to the UN General Assembly, 1979[118]

Castro considered Africa to be "the weakest link in the imperialist chain", in November 1975 he ordered 230 military advisors into Southern Africa to aid the Marxist

In 1977, the

In 1979, the Conference of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was held in Havana, where Castro was selected as NAM president, a position he held till 1982. In his capacity as both President of the NAM and of Cuba he appeared at the United Nations General Assembly in October 1979 and gave a speech on the disparity between the world's rich and poor. His speech was greeted with much applause from other world leaders,[118][127] though his standing in NAM was damaged by Cuba's abstinence from the U.N.'s General Assembly condemnation of the Soviet–Afghan War.[127] Cuba's relations across North America improved under Mexican President Luis Echeverría, Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau,[128] and U.S. President Jimmy Carter. Carter continued criticizing Cuba's human rights abuses, but adopted a respectful approach which gained Castro's attention. Considering Carter well-meaning and sincere, Castro freed certain political prisoners and allowed some Cuban exiles to visit relatives on the island, hoping that in turn Carter would abolish the economic embargo and stop CIA support for militant dissidents.[129][130]

Reagan and Gorbachev (1980–1990)

By the 1980s, Cuba's economy was again in trouble, following a decline in the market price of sugar and 1979's decimated harvest.[131][132] Desperate for money, Cuba's government secretly sold off paintings from national collections and illicitly traded for U.S. electronic goods through Panama.[133] Increasing numbers of Cubans fled to Florida, who were labelled "scum" by Castro.[134] In one incident, 10,000 Cubans stormed the Peruvian Embassy requesting asylum, and so the U.S. agreed that it would accept 3,500 refugees. Castro conceded that those who wanted to leave could do so from Mariel port. Hundreds of boats arrived from the U.S., leading to a mass exodus of 120,000; Castro's government took advantage of the situation by loading criminals and the mentally ill onto the boats destined for Florida.[135][136] In 1980, Ronald Reagan became U.S. president and then pursued a hard line anti-Castro approach,[137][138] and by 1981, Castro was accusing the U.S. of biological warfare against Cuba.[138]

Although despising Argentina's right wing military junta, Castro supported them in the 1982 Falklands War against the United Kingdom and offered military aid to the Argentinians.[139] Castro supported the leftist New Jewel Movement that seized power in Grenada in 1979, sent doctors, teachers, and technicians to aid the country's development, and befriended the Grenadine President Maurice Bishop. When Bishop was murdered in a Soviet-backed coup by hardline Marxist Bernard Coard in October 1983, Castro cautiously continued supporting Grenada's government. However, the U.S. used the coup as a basis for invading the island. Cuban construction workers died in the conflict, with Castro denouncing the invasion and comparing the U.S. to Nazi Germany.[140][141] Castro feared a U.S. invasion of Nicaragua and sent Arnaldo Ochoa to train the governing Sandinistas in guerrilla warfare, but received little support from the Soviet Union.[142]

In 1985,

By November 1987, Castro began spending more time on the Angolan Civil War, in which the Marxists had fallen into retreat. Angolan President

The Special Period (1991–2000)

With favourable trade from the Eastern Bloc ended, Castro publicly declared that Cuba was entering a "

"We do not have a smidgen of capitalism or neo-liberalism. We are facing a world completely ruled by neo-liberalism and capitalism. This does not mean that we are going to surrender. It means that we have to adopt to the reality of that world. That is what we are doing, with great equanimity, without giving up our ideals, our goals. I ask you to have trust in what the government and party are doing. They are defending, to the last atom, socialist ideas, principles and goals."

— Fidel Castro explaining the reforms of the Special Period[165]

In 1991, Havana

Castro recognised the need for reform if Cuban socialism was to survive in a world now dominated by capitalist free markets. In October 1991, the Fourth Congress of the Cuban Communist Party was held in Santiago, at which a number of important changes to the government were announced. Castro would step down as head of government, to be replaced by the much younger

Castro's government decided to diversify its economy into

In the early 1990s, Castro embraced

The Pink Tide (2000–2006)

This section needs expansion with: Information on Cuba's increasingly good relationship with the Pink Tide and its co-founding of ALBA. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

"As I have said before, the ever more sophisticated weapons piling up in the arsenals of the wealthiest and the mightiest can kill the illiterate, the ill, the poor and the hungry but they cannot kill ignorance, illnesses, poverty or hunger."

— Fidel Castro's speech at the

Mired in economic problems, Cuba would be aided by the election of socialist and anti-imperialist Hugo Chávez to the Venezuelan Presidency in 1999.[188] In 2000, Castro and Chávez signed an agreement through which Cuba would send 20,000 medics to Venezuela, in return receiving 53,000 barrels of oil per day at preferential rates; in 2004, this trade was stepped up, with Cuba sending 40,000 medics and Venezuela providing 90,000 barrels a day.[189][190] That same year, Castro initiated Mision Milagro, a joint medical project which aimed to provide free eye operations on 300,000 individuals from each nation.[191] The alliance boosted the Cuban economy, and in May 2005 Castro doubled the minimum wage for 1.6 million workers, raised pensions, and delivered new kitchen appliances to Cuba's poorest residents.[188] Some economic problems remained; in 2004, Castro shut down 118 factories, including steel plants, sugar mills and paper processors to compensate for the crisis of fuel shortages.[192]

Evo Morales of Bolivia has described him as "the grandfather of all Latin American revolutionaries".[193] In contrast to the improved relations between Cuba and a number of leftist Latin American states, in 2004 it broke off diplomatic ties with Panama after centrist President Mireya Moscoso pardoned four Cuban exiles accused of attempting to assassinate Cuban President Fidel Castro in 2000. Diplomatic ties were reinstalled in 2005 following the election of leftist President Martín Torrijos.[194]

Castro's improving relations across Latin America were accompanied by continuing animosity towards the U.S. However, after massive damage caused by

At a summit meeting of sixteen Caribbean countries in 1998, Castro called for regional unity, saying that only strengthened cooperation between Caribbean countries would prevent their domination by rich nations in a global economy.[198] Caribbean nations have embraced Cuba's Fidel Castro while accusing the US of breaking trade promises. Castro, until recently a regional outcast, has been increasing grants and scholarships to the Caribbean countries, while US aid to those has dropped 25% over the past five years.[199] Cuba has opened four additional embassies in the Caribbean Community including: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Suriname, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. This development makes Cuba the only country to have embassies in all independent countries of the Caribbean Community.[200]

Castro was known to be a friend of former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and was an honorary pall bearer at Trudeau's funeral in October 2000. They had continued their friendship after Trudeau left office until his death. Canada became one of the first American allies openly to trade with Cuba. Cuba still has a good relationship with Canada. On 20 April 1998, Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien arrived in Cuba to meet President Castro and highlight their close ties. He is the first Canadian government leader to visit the island since Pierre Trudeau was in Havana on 16 July 1976.[201]

Stepping down (2006–2008)

This section needs expansion with: Information on Castro's second presidency of the NAM.. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

On July 31, 2006, Castro delegated all his duties to his brother

In a letter dated February 18, 2008, Castro announced that he would not accept the positions of President of the Council of State and Commander in Chief at the February 24 National Assembly meetings,[211][212][213] stating that his health was a primary reason for his decision, remarking that "It would betray my conscience to take up a responsibility that requires mobility and total devotion, that I am not in a physical condition to offer".[214] On February 24, 2008, the National Assembly of People's Power unanimously voted Raúl as president.[215] Describing his brother as "not substitutable", Raúl proposed that Fidel continue to be consulted on matters of great importance, a motion unanimously approved by the 597 National Assembly members.[216]

See also

- Cuban Revolution

- History of Cuba

- History of land reform in Cuba

- Timeline of Cuban history

- Politics of Cuba

References

Notes

Footnotes

Other

Footnotes

- ^ Authors, Multiple (2015). Oxford IB Diploma Programme: Authoritarian States Course Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 63.

- ^ "Cuba (09/01)".

- ISBN 978-0786474707.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 173; Quirk 1993, p. 228.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 174–177; Quirk 1993, pp. 236–242; Coltman 2003, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 177; Quirk 1993, p. 243; Coltman 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 177–178; Coltman 2003, pp. 159–160

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 262–269, 281.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 234.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 186.

- ^ Ley de Reforma Urbana 1960 (Cuba) in Stuart Grider, “A Proposal for the Marketization of Housing in Cuba: The Limited Equity Housing Corporation: A New Form of Property,” The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 27, no. 3 (Spring-Summer 1996): 473, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40176383?seq=21.

- ^ Roberto Veiga, “Informe Central del XXXIV Consejo Nacional de la CTC,” Granma 11, no. 31 (1975): 5 in Carmelo Mesa-Lago, "The Economy of Socialist Cuba", 172.

- ^ Grider, “A Proposal for the Marketization of Housing in Cuba,” 472; Jill Hamberg, Under Construction: Housing Policy in Revolutionary Cuba (New York: Center for Cuban Studies, 1986), 31, note 9.

- ^ Ley de Reforma Urbana 1960 in Grider, “A Proposal for the Marketization of Housing in Cuba,” 472; Banco Nacional de Cuba, Desarrollo y perspectivas de la economía cubana (Havana: Banco Nacional de Cuba, 1975), 104 in Mesa-Lago, Economy of Socialist Cuba, 172; Louis A. Pérez, Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, 280.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 176–177; Quirk 1993, p. 248; Coltman 2003, pp. 161–166.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 181–183; Quirk 1993, pp. 248–252; Coltman 2003, p. 162.

- ISBN 1-55546-835-7, pg 66

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 179.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 280; Coltman 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 195–197; Coltman 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 181, 197; Coltman 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 167; Ros 2006, pp. 159–201; Franqui 1984, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 197; Coltman 2003, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 202; Quirk 1993, p. 296.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 189–190, 198–199; Quirk 1993, pp. 292–296; Coltman 2003, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 205–206; Quirk 1993, pp. 316–319; Coltman 2003, p. 173.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 201–202; Quirk 1993, p. 302; Coltman 2003, p. 172.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 202, 211–213; Quirk 1993, pp. 272–273; Coltman 2003, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 214; Quirk 1993, p. 349; Coltman 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 215.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 206–209; Quirk 1993, pp. 333–338; Coltman 2003, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 209–210; Quirk 1993, p. 337.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 339.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 300; Coltman 2003, p. 176.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 125; Quirk 1993, p. 300.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233; Quirk 1993, p. 345; Coltman 2003, p. 176.

- ^ Quirk 1993. p. 313.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 330.

- ^ a b c d e Bourne 1986, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 275–276; Quirk 1993, p. 324.

- ^ Wyatt MacGaffey and Clifford R. Barnett, Twentieth Century Cuba: The Background of the Castro Revolution, 2nd Ed. (Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1965), 207.

- ^ Carmelo Mesa-Lago, The Labor Force, Employment, Unemployment and Underemployment in Cuba: 1899-1970 (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1972), 49.

- ^ Mesa-Lago, Economy of Socialist Cuba, 124.

- ^ Consejo Nacional de Economía, Empleo y desempleo de la fuerza trabajadora (1958); International Labour Organisation, Yearbook of Labour Statistics, 1960, 188; Cuba, Oficina Nacional de los Censos Demográficos y Electoral, Muestro sobre empleo, sub-empleo y desempleo (Havana: Oficina Nacional de los Censos Demográficos y Electoral, 1959-61); Cuba, Dirección Central de Estadística, Boletín Estadístico de Cuba 1966 (Havana: Junta Central de Planificación (JUCEPLAN)), 24 [Note: these statistical annuals, published from 1964-71, will be referred to here as Boletín]; Boletín 1968, 18-22, Boletín 1970, 24; Jorge Risquet, “Comparecencia sobre problemas de la fuerza de trabajo,” Granma (1 August 1970): 2-3; Cuba, Dirección Central de Estadística, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 1975 (Havana: JUCEPLAN, 1975), 44; Banco Nacional de Cuba, Present Planning and Management System of the National Economy of the Republic of Cuba (Havana: Banco Nacional de Cuba, 1977), 9 and Banco Nacional, Present Planning (1978), 9, (all cited in Mesa-Lago, Economy of Socialist Cuba, 111 and 122 and Mesa-Lago, The Labor Force, 27 and 36).

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 226.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 215–216; Quirk 1993, pp. 353–354, 365–366; Coltman 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 217–220; Quirk 1993, pp. 363–367; Coltman 2003, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 371.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 369; Coltman 2003, pp. 180, 186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 222–225; Quirk 1993, pp. 370–374; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 226–227; Quirk 1993, pp. 375–378; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 230; Quirk 1993, pp. 387, 396; Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 231, Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 405.

- ^ Bourne 1987, pp. 230–234, Quirk, pp. 395, 400–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 232–234, Quirk 1993, pp. 397–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 232, Quirk 1993, p. 397.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 188–189.

- ^ "Castro admits 'injustice' for gays and lesbians during revolution", CNN, Shasta Darlington, August 31, 2010.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233, Quirk 1993, pp. 203–204, 410–412, Coltman 2003, p. 189.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 234–236, Quirk 1993, pp. 403–406, Coltman 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 258–259, Coltman 2003, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 238–239, Quirk 1993, p. 425, Coltman 2003, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 239, Quirk 1993, pp. 443–434, Coltman 2003, pp. 199–200, 203.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 241–242, Quirk 1993, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 245–248.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 204–205.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 249.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 213.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 263.

- ^ "Cuba Once More", by Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964, p. 23.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 255.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 211.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 255–256, 260.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 211–212.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 267–268.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 216.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 265.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 214.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 267.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 269.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 269–270.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 270–271.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Castro, Fidel (August 1968). "Castro comments on Czechoslovakia crisis". FBIS.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 227.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 229.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 274.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 230.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 276–277.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 277.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 232–233.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 278–280.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 233–236, 240.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 237–238.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 238.

- ^ a b Bourne 1986. pp. 283–284.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 239.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 284.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 239–240.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 240.

- ^ Macrotrends, “Cuba Economic Growth 1970-2022,” accessed May 14, 2022, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/CUB/cuba/economic-growth-rate.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 282.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 283.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 240–241.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 245.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 281, 284–287.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 242–243.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 243.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 243–244.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 291–292.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 249.

- ^ "Recipient Grants: Center for a Free Cuba". August 25, 2006. Archived from the original on August 28, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2006.

- ^ O'Grady, Mary Anastasia (October 30, 2005). "Counting Castro's Victims". Wall Street Journal. Center for a Free Cuba. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2006.

- ^ a b Bourne 1986. p. 294.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 244–245.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 289.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 247–248.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 250.

- ^ a b Gott 2004. p. 288.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 255.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 295.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 251–252.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 296.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 252.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 253.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 297.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 253–254.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 254–255.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 256.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 257.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 260–261.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 276.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 258–266.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 279–286.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 224.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 257–258.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 276–279.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 277.

- ^ a b c Gott 2004. p. 286.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 267–268.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 268–270.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 270–271.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 271.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 287–289.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 282.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. pp. 274–275.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 275.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 290–291.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 305–306.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 291–292.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 272–273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 275–276.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 314.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 297–299.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 298–299.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 287.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 273–274.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 276–281, 284, 287.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 291–294.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 288.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 290, 322.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 294.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 278, 294–295.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 309.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 309–311.

- ^ Gott 2004. pp. 306–310.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 312.

- ^ "untitled" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 283.

- ^ Gott 2004. p. 279.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 304.

- ^ "Speech by Fidel Castro to the International Conference on Financing and Development, Monterrey, March 21, 2002". Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Kozloff 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Marcano & Tyszka 2007, pp. 213–215; Kozloff 2008, pp. 23–24.

- Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the originalon 1 October 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ Kozloff 2008, p. 21.

- ^ "Cuba to shut plants to save power". BBC News. September 30, 2004. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ "Spiegel interview with Bolivia's Evo Morales". Der Spiegel. August 28, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Stephen (August 21, 2005). "Cuba and Panama restore relations". BBC News. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ "Castro welcomes one-off US trade". BBC News. November 17, 2001. Retrieved May 19, 2006.

- ^ "US food arrives in Cuba". BBC News. December 16, 2001. Retrieved May 19, 2006.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 320.

- ^ "Castro calls for Caribbean unity". BBC News. August 21, 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ "Castro finds new friends". BBC News. 25 August 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ "Cuba opens more Caribbean embassies". Caribbean Net News. March 13, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2006.

- ^ "Canadian PM visits Fidel in April". BBC News. April 20, 1998. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ Reaction Mixed to Castro’s Turnover of Power Archived 2014-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. PBS. August 1, 2006

- ^ Castro, Fidel (March 22, 2011). "My Shoes Are Too Tight". Juventud Rebelde. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Castro says he resigned as Communist Party chief 5 years ago". CNN. March 22, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Pretel, Enrique Andres (February 28, 2007). "Cuba's Castro says recovering, sounds stronger". Reuters. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Pearson, Natalie Obiko (13 April 2007). "Venezuela: Ally Castro Recovering". Associated Press.

- ^ "Castro resumes official business". BBC News. April 21, 2007. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ^ Marcano and Tyszka 2007. p. 287.

- ^ Sivak 2008. p. 52.

- ^ "Bush wishes Cuba's Castro would disappear". Reuters. 28 June 2007. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ Castro, Fidel (February 18, 2008). "Message from the Commander in Chief". Diario Granma. Comité Central del Partido Comunista de Cuba. Retrieved May 20, 2011.(in Spanish)

- ^ "Fidel Castro announces retirement". BBC News. February 18, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ "Fidel Castro stepping down as Cuba's leader". Reuters. February 18, 2008. Archived from the original on January 3, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ "Fidel Castro announces retirement". BBC News. February 19, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ "Raul Castro named Cuban president". BBC. February 24, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "CUBA: Raúl Shares His Seat with Fidel". Ipsnews.net. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

Bibliography

- Benjamin, Jules R. (1992). The United States and the Origins of the Cuban Revolution: An Empire of Liberty in an Age of National Liberation. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691025360.

- Bohning, Don (2005). The Castro Obsession: U.S. Covert Operations Against Cuba, 1959–1965. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1574886764.

- ISBN 978-0396085188.

- ISBN 978-0300107609.

- Geyer, Georgie Anne (1991). Guerrilla Prince: The Untold Story of Fidel Castro. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0316308939.

- ISBN 978-0300104110.

- Marcano, Christina; Barrera Tyszka, Alberto (2007). Hugo Chávez: The Definitive Biography of Venezuela's Controversial President. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679456667.

- ISBN 978-0393034851.

- ISBN 978-0006388456.

- Skierka, Volka (2006). Fidel Castro: A Biography. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-0745640815.

- Von Tunzelmann, Alex (2011). Red Heat: Conspiracy, Murder, and the Cold War in the Caribbean. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805090673.

- Wilpert, Gregory (2007). Changing Venezuela by Taking Power: The History and Policies of the Chávez Government. London and New York: Verso. ISBN 978-1844675524.