Christendom

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

| Christianity portal |

Christendom[2][3] refers to Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant[4] or prevails.[2]

Following the spread of Christianity from the

Terminology

The

The current sense of the word of "lands where Christianity is the dominant religion"

Canadian theology professor Douglas John Hall stated (1997) that "Christendom" [...] means literally the dominion or sovereignty of the Christian religion."[4] Thomas John Curry, Roman Catholic auxiliary bishop of Los Angeles, defined (2001) Christendom as "the system dating from the fourth century by which governments upheld and promoted Christianity."[15] Curry states that the end of Christendom came about because modern governments refused to "uphold the teachings, customs, ethos, and practice of Christianity."[15] British church historian Diarmaid MacCulloch described (2010) Christendom as "the union between Christianity and secular power."[16]

Christendom was originally a medieval concept which has steadily evolved since the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the gradual rise of the Papacy more in religio-temporal implications practically during and after the reign of Charlemagne; and the concept let itself be lulled in the minds of the staunch believers to the archetype of a holy religious space inhabited by Christians, blessed by God, the Heavenly Father, ruled by Christ through the Church and protected by the Spirit-body of Christ; no wonder, this concept, as included the whole of Europe and then the expanding Christian territories on earth, strengthened the roots of Romance of the greatness of Christianity in the world.[17]

There is a common and nonliteral sense of the word that is much like the terms

History

Rise of Christendom

Early Christianity spread in the Greek/Roman world and beyond as a 1st-century

The post-apostolic period concerns the time roughly after the death of the apostles when bishops emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations. The earliest recorded use of the terms Christianity (Greek Χριστιανισμός) and

According to Malcolm Muggeridge (1980), Christ founded Christianity, but Constantine founded Christendom.[22] Canadian theology professor Douglas John Hall dates the 'inauguration of Christendom' to the 4th century, with Constantine playing the primary role (so much so that he equates Christendom with "Constantinianism") and Theodosius I (Edict of Thessalonica, 380) and Justinian I[a] secondary roles.[24]

Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

"Christendom" has referred to the

The Church gradually became a defining institution of the Roman Empire.

As the

On Christmas Day 800 AD,

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and the Latin West. In the Greek philosopher

... For a thousand years Europe was ruled by an order of guardians considerably like that which was visioned by our philosopher. During the Middle Ages it was customary to classify the population of Christendom into laboratores (workers), bellatores (soldiers), and oratores (clergy). The last group, though small in number, monopolized the instruments and opportunities of culture, and ruled with almost unlimited sway half of the most powerful continent on the globe. The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church. In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 AD onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians]... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them....[34]

Later Middle Ages and Renaissance

After the

In the East, Christendom became more defined as the

The

Christendom ultimately was led into specific crisis in the

Before the modern period, Christendom was in a general crisis at the time of the

Professor Frederick J. McGinness described Rome as essential in understanding the legacy the Church and its representatives encapsulated best by The Eternal City:

No other city in Europe matches Rome in its traditions, history, legacies, and influence in the Western world. Rome in the Renaissance under the papacy not only acted as guardian and transmitter of these elements stemming from the Roman Empire but also assumed the role as artificer and interpreter of its myths and meanings for the peoples of Europe from the Middle Ages to modern times... Under the patronage of the popes, whose wealth and income were exceeded only by their ambitions, the city became a cultural center for master architects, sculptors, musicians, painters, and artisans of every kind...In its myth and message, Rome had become the sacred city of the popes, the prime symbol of a triumphant Catholicism, the center of orthodox Christianity, a new Jerusalem.[51]

It is clearly noticeable that the popes of the Italian Renaissance have been subjected by many writers with an overly harsh tone. Pope Julius II, for example, was not only an effective secular leader in military affairs, a deviously effective politician but foremost one of the greatest patron of the Renaissance period and person who also encouraged open criticism from noted humanists.[52]

The blossoming of renaissance humanism was made very much possible due to the universality of the institutions of Catholic Church and represented by personalities such as

The enterprise of individuals or of small aristocratic bodies has meantime sown the world which we call civilised with some seeds and nuclei of order. There are scattered about a variety of churches, industries, academies, and governments. But the universal order once dreamt of and nominally almost established, the empire of universal peace, all-permeating rational art, and philosophical worship, is mentioned no more. An unformulated conception, the prerational ethics of private privilege and national unity, fills the background of men's minds. It represents feudal traditions rather than the tendency really involved in contemporary industry, science, or philanthropy. Those dark ages, from which our political practice is derived, had a political theory which we should do well to study; for their theory about a universal empire and a Catholic church was in turn the echo of a former age of reason, when a few men conscious of ruling the world had for a moment sought to survey it as a whole and to rule it justly.[53]

Reformation and Early Modern era

Developments in

In

The

End of Christendom

The

Writing in 1997, Canadian

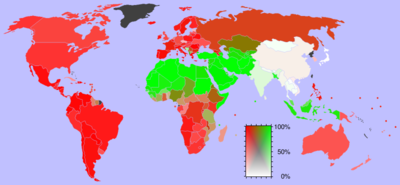

Changes in worldwide Christianity over the last century have been significant, since 1900, Christianity has spread rapidly in the

Classical culture

Though Western culture contained several polytheistic religions during its early years under the

Christianity had a significant impact on education and science and medicine as the church created the bases of the Western system of education,

Art and literature

Writings and poetry

Supplemental arts

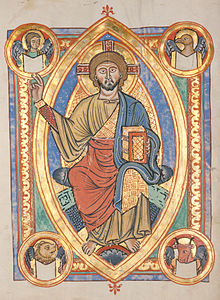

Illumination

An

Most illuminated manuscripts were created as codices, which had superseded scrolls; some isolated single sheets survive. A very few illuminated manuscript fragments survive on papyrus. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most commonly of calf, sheep, or goat skin), but most manuscripts important enough to illuminate were written on the best quality of parchment, called vellum, traditionally made of unsplit calfskin, though high quality parchment from other skins was also called parchment.[95]

Iconography

Christian art began, about two centuries after Christ, by borrowing motifs from

An

Each saint has a story and a reason why he or she led an exemplary life.

Architecture

Buildings were at first adapted from those originally intended for other purposes but, with the rise of distinctively ecclesiastical architecture, church buildings came to influence secular ones which have often imitated religious architecture. In the 20th century, the use of new materials, such as concrete, as well as simpler styles has had its effect upon the design of churches and arguably the flow of influence has been reversed.

Philosophy

Christian civilization

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article and should be moved to Christianity and science instead. (January 2018) ) |

Medieval conditions

The

Significant in this respect were advances within the fields of

Renaissance innovations

During the

Professor Noah J Efron says that "Generations of historians and sociologists have discovered many ways in which Christians, Christian beliefs, and Christian institutions played crucial roles in fashioning the tenets, methods, and institutions of what in time became modern science. They found that some forms of Christianity provided the motivation to study nature systematically..."[109] Virtually all modern scholars and historians agree that Christianity moved many early-modern intellectuals to study nature systematically.[110]

Demographics

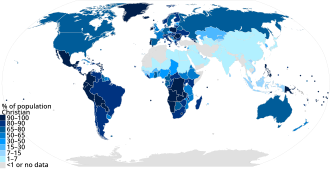

Geographic spread

In 2009, according to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Christianity was the majority religion in Europe (including Russia) with 80%, Latin America with 92%, North America with 81%, and Oceania with 79%.[111] There are also large Christian communities in other parts of the world, such as China, India and Central Asia, where Christianity is the second-largest religion after Islam. The United States is home to the world's largest Christian population, followed by Brazil and Mexico.[112]

Many Christians not only live under, but also have an official status in, a

Number of adherents

The estimated number of Christians in the world ranges from 2.2 billion[125][126][127][128] to 2.4 billion people.[b] The faith represents approximately one-third of the world's population and is the largest religion in the world,[127] with the three largest groups of Christians being the Catholic Church, Protestantism, and the Eastern Orthodox Church.[129] The largest Christian denomination is the Catholic Church, with an estimated 1.2 billion adherents.[130]

| Tradition | Followers | % of the Christian population | % of the world population | Follower dynamics | Dynamics in- and outside Christianity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic Church | 1,094,610,000 | 50.1 | 15.9 | ||

| Protestantism | 800,640,000 | 36.7 | 11.6 | ||

Orthodoxy

|

260,380,000 | 11.9 | 3.8 | ||

| Other Christianity | 28,430,000 | 1.3 | 0.4 | ||

| Christianity | 2,184,060,000 | 100 | 31.7 |

Notable Christian organizations

A

Various organizations include:

- In the Roman Catholic Church, religious institutes and secular institutes are the major forms of institutes of consecrated life, similar to which are societies of apostolic life. They are organizations of laity or clergy who live a common life under the guidance of a fixed rule and the leadership of a superior. (ed., see Category: Catholic orders and societies for a particular listing.)

- Anglican religious orders are communities of laity or clergy in the Anglican churches who live under a common rule of life. (ed., see Category: Anglican organizations for a particular listing)

Christianity law and ethics

Church and state framing

Within the framework of Christianity, there are at least three possible definitions for Church law. One is the Torah/Mosaic Law (from what Christians consider to be the

Under the

Thomas Aquinas thoroughly discussed that human law is positive law which means that it is natural law applied by governments to societies. All human laws were to be judged by their conformity to the natural law. An unjust law was in a sense no law at all. At this point, the natural law was not only used to pass judgment on the moral worth of various laws, but also to determine what the law said in the first place. This could result in some tension.[133] Late ecclesiastical writers followed in his footsteps.

Democratic ideology

Women's roles

Attitudes and beliefs about the roles and responsibilities of women in Christianity vary considerably today as they have throughout the last two millennia—evolving along with or counter to the societies in which Christians have lived. The Bible and Christianity historically have been interpreted as excluding women from church leadership and placing them in submissive roles in marriage. Male leadership has been assumed in the church and within marriage, society and government.[134]

Some contemporary writers describe the role of women in the life of the church as having been downplayed, overlooked, or denied throughout much of Christian history.

See also

- Caesaropapism – System with state control of the Church

- Christian republic – Government that is both Christian and republican

- The City of God – Book by Augustine of Hippo

- Constantine the Great and Christianity

- Constantinian shift – Political and theological changes

- Dominion theology – Ideology seeking Christian rule

- Ecumenism – Cooperation between Christian denominations

- Holy Roman Emperor – Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

- Integralism – Principle that the Catholic faith should be the basis of public law and policy

- Res publica Christiana – Medieval term for international community of Christian peoples and states

- Role of Christianity in civilization

- Union of Christendom, a traditional Catholic view of ecumenism

Notes

- ^ In 529, Justinian closed the Neoplatonic Academy of Athens, a last bulwark of pagan philosophy, made rigorous efforts to exterminate Arianism and Montanism, personally campaigned against Monophysitism, and made Chalcedonian Christianity the Byzantine state religion.[23]

- ^ Current sources are in general agreement that Christians make up about 33% of the world's population—slightly over 2.4 billion adherents in mid-2015.

References

- ^ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population" (PDF). Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b See Merriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"

- ISBN 978-1-58836-684-9.

- ^ ISBN 9781579109844. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

"Christendom" [...] means literally the dominion or sovereignty of the Christian religion.

- ISBN 9780521616645. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "christendom. §1.3 Scheidingen". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ Chazan, p. 5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ISBN 1405108991.

- ^ a b "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas Woods, Jr". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ISBN 9781101189993. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ "Translate christendom from Dutch to English".

- ^ "CHRISTENTUM - Translation in English - bab.la".

- ^ "Christendom | Origin and meaning of christendom by Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ ISBN 9780190287061. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ a b MacCulloch (2010), p. 1024–1030.

- ISBN 978-81-269-1366-4.

- ^ ISBN 9780813216836.

- ^ Acts 3:1; Acts 5:27–42; Acts 21:18–26; Acts 24:5; Acts 24:14; Acts 28:22; Romans 1:16; Tacitus, Annales xv 44; Josephus Antiquities xviii 3; Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience Volume II chapter 5; The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion page 158[failed verification].

- ^ Walter Bauer, Greek-English Lexicon; Ignatius of Antioch Letter to the Magnesians 10, Letter to the Romans (Roberts-Donaldson tr., Lightfoot tr., Greek text). However, an edition presented on some websites, one that otherwise corresponds exactly with the Roberts-Donaldson translation, renders this passage to the interpolated inauthentic longer recension of Ignatius's letters, which does not contain the word "Christianity."

- ISBN 978-1-61025-041-2. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

The ante-Nicene age ... is the natural transition from the Apostolic age to the Nicene age.

- ^ Robert Peel (18 February 1981). "Impish defense of Christianity; The End of Christendom, by Malcolm Muggeridge". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Justinianus I". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ a b Hall (2002), p. 1–9.

- ^ Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 699–701, see page 700, para 2, half way down.

The whole issue had, in fact, become confused with the confusion of functions of the Church and State. In the view of the Church of England the ultimate governance of the Christian community, in things spiritual and temporal, was vested not in the clergy but in the "Christian prince" as the vicegerent of God.

- ^ The church in the Roman empire before A.D. 170, Part 170 By Sir William Mitchell Ramsay

- ^ Boyd, William Kenneth (1905). The ecclesiastical edicts of the Theodosian code, Columbia University Press.

- ^ Cameron 2006, p. 42.

- ^ Cameron 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Browning 1992, pp. 198–208.

- ISBN 978-0-520-07964-9.

- ^ Willis Mason West (1904). The ancient world from the earliest times to 800 A.D. ... Allyn and Bacon. p. 551.

- ISBN 978-0-631-22138-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-671-69500-2. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Shaping a global theological mind By Darren C. Marks. Page 45

- ^ Somerville, R. (1998). Prefaces to Canon Law books in Latin Christianity: Selected translations, 500-1245; commentary and translations. New Haven [u.a.: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ VanDeWiel, C. (1991). History of canon law. Leuven: Peeters Press.

- ^ Canon law and the Christian community By Clarence Gallagher. Gregorian & Biblical BookShop, 1978.

- ^ Catholic Church., Canon Law Society of America., Catholic Church., & Libreria editrice vaticana. (1998). Code of canon law, Latin-English edition: New English translation. Washington, DC: Canon Law Society of America.

- ^ Mango, C. (2002). The Oxford history of Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Angold, M. (1997). The Byzantine Empire, 1025-1204: A political history. New York: Longman.

- ^ Schevill, Ferdinand (1922). The History of the Balkan Peninsula: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Harcourt, Brace and Company. p. 124.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1878). The history of creeds. Harper.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ MacCulloch (2010), p. 625.

- ^ Lazare (1903), p. 61

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Stump, P. H. (1994). The reforms of the Council of Constance, 1414-1418. Leiden: E.J. Brill

- ^ The Cambridge Modern History. Vol 2: The Reformation (1903)[permanent dead link].

- ^ Norris, Michael (August 2007). "The Papacy during the Renaissance". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ McGinness, Frederick (26 August 2011). "Papal Rome". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Cheney, Liana (26 August 2011). "Background for Italian Renaissance". University of Massachusetts Lowell. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Santayana, George (1982). The Life of Reason. New York: Dover Publications. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- nation-state

- ^ "The Anglican Domain: Church History".

- ^ "Peace of Augsburg | Germany [1555], Religion & Politics | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-09-18. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ a b "The Peace of Westphalia" (PDF). University of Oregon. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Žalta, Anja. 2004. Protestantizem in bukovništvo med koroškimi Slovenci. Anthropos 36(1/4): 1–23, p. 7.

- ^ Uwe Becker, Europese democratieën: vrijheid, gelijkheid, solidariteit en soevereiniteit in praktijk

- ^ "Wars of Religion". Britannica Online. June 26, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population" (PDF). Pew Research Center.

- ^ ISBN 9780931888755.

- LCCN 2010046058.

- ^ Kim, Sebastian; Kim, Kirsteen (2008). Christianity as a World Religion. London: Continuum. p. 2.

- ^ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population" (PDF). Pew Research Center.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. xix–xx

- ^ Verger 1999

- ^ "Valetudinaria". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ISBN 978-0-19-505523-8.

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ Britannica.com Forms of Christian education

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ISBN 978-2868473448. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ISBN 0691128073, p. 68.

- ^ Woods 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Britannica.com Jesuit

- ^ Britannica.com Church and social welfare

- ^ Britannica.com Care for the sick

- ^ Britannica.com Property, poverty, and the poor,

- ^ Weber, Max (1905). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

- ISBN 978-0-521-89057-1, pp. 189, 208

- ^ Britannica.com Church and state

- Banister Fletcher, History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- ^ Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: "Charting the 'Rise of the West': Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), pp. 409–445 (416, table 1)

- ^ Eveleigh, Bogs (2002). Baths and Basins: The Story of Domestic Sanitation. Stroud, England: Sutton.

- ^ Christianity in Action: The History of the International Salvation Army p.16

- ^ Britannica.com The tendency to spiritualize and individualize marriage

- ^ Chadwick, Owen p. 242.

- ^ Hastings, p. 309.

- ^ Watson Kirkconnell (1952), The Celestial Cycle: The Theme of Paradise Lost in World Literature with Translations of the Major Analogues, University of Toronto Press. Pages 569-570.

- ^ a b c Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Rholetter, Wylene (2018). "Written Word in Medieval Society". Salem Press Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Differences between Parchment, Vellum and Paper". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- ^ "Answering Eastern Orthodox Apologists regarding Icons". The Gospel Coalition.

- ^ Jenner, Henry (2004) [1910]. Christian Symbolism. Kessinger Publishing. p. xiv.

- ISBN 978-1-4073-6071-3.

- ^ Fletcher, Banister. A History of Architecture

- ^ Derrick, Andrew (2017). "19th- and 20th-Century Roman Catholic Churches". Historic England. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark. "Byzantine Architecture". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ Murray, Michael J.; Rea, Michael (2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Philosophy and Christian Theology. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Scholasticism". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ Alfred Crosby described some of this technological revolution in his The Measure of Reality : Quantification in Western Europe, 1250–1600 and other major historians of technology have also noted it.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (8 May 2012). "Christianity and the rise of western science". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Noll, Mark, Science, Religion, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Science and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015

- ISBN 978-0-520-05538-4

- ISBN 0521814561.

- ISBN 9780674057418.

- ISBN 9780674057418.

- ISBN 9781615353668. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "The Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population". 2011-12-19.

- ^ "Argentina". Britannica.com. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ^ "Gov. Pataki Honors 1700th Anniversary of Armenia's Adoption of Christianity as a state religion". Aremnian National Committee of America. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- ^ "Costa Rica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Denmark". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "El Salvador". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Church and State in Britain: The Church of privilege". Centre for Citizenship. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Iceland". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Liechtenstein". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Malta". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Monaco". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Norway". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Vatican". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ 33.39% of ~7.2 billion world population (under the section 'People') "World". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 27 July 2022. (Archived 2022 edition.)

- ^ "Christianity 2015: Religious Diversity and Personal Contact" (PDF). gordonconwell.edu. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ^ a b "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ ANALYSIS (2011-12-19). "Global Christianity". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Hinnells, The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, p. 441.

- ^ "How many Roman Catholics are there in the world?". BBC News. March 14, 2013. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population". 19 December 2011.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Burns, "Aquinas's Two Doctrines of Natural Law."

- ISBN 0-86554-493-X

- ISBN 9781856840453.

Bibliography

- 21st century Sources

- ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- Lazare, Bernard (1903). Antisemitism: Its History and Causes. New York: International Library.

- 20th century sources

- Browning, Robert (1992). The Byzantine Empire. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-0754-4.

- The Return of Christendom. Macmillan. 1922.

- Andrew Dickson White (1897). A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. D. Appleton.

- F. G. Cole (1908). Mother of All Churches: A Brief and Comprehensive Handbook of the Holy Eastern Orthodox Church. Skeffington.

- 19th century sources

- Hull, Moses. Encyclopedia of Biblical Spiritualism; Or, A Concordance to the Principal Passages of the Old and New Testament Scriptures Which Prove or Imply Spiritualism; Together with a Brief History of the Origin of Many of the Important Books of the Bible. Chicago: M. Hull, 1895. (ed., reprint version is available)

- Bosanquet, Bernard. The Civilization of Christendom, And Other Studies. London: S. Sonnenschein, 1893.

- The History of Teachings of the Early Church, as a Basis for the Re-union of Christendom: Lectures. E. & J. B. Young. 1893.

- John Hodson Egar (1887). Christendom; ecclesiastical and political, from Constantine to the Reformation. J. Pott.

- The Churches of Christendom. Macniven and Wallace. 1884.

- Charles, Elizabeth (1880). Sketches of the women of Christendom, by the author of 'Chronicles of the Schönberg-Cotta family'.

- Naville, Ernest (1880). The Christ: Seven lectures. T. & T. Clark.

- George William Cox (1870). Latin and Teutonic Christendom: An Historical Sketch. Longmans, Green & Company.

- Girdlestone, Charles (1870). Christendom, sketched from history in the light of holy Scripture. Published for the Author by Sampson Low, Son, & Marston.

- John Radford Thomson (1867). Symbols of Christendom: an elementary text-book.

- Thomas William Allies (1865). The formation of Christendom. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green.

- Stearns, George (1857). The mistake of Christendom; or, Jesus and His Gospel before Paul and Christianity. B. Marsh.

- Johnson, Richard (1824). The Renowned History of the Seven Champions of Christendom: St. George of England, St. Denis of France, St. James of Spain, St. Anthony of Italy, St. Andrew of Scotland, St. Patrick of Ireland, and St. David of Wales, and Their Sons. W. Baynes.

Further reading

- Bainton, Roland H. (1966). Christendom: a Short History of Christianity and Its Impact on Western Civilization, in series, Harper Colophon Books. New York: Harper & Row. 2 vol., ill.

- Molland, Einar (1959) Christendom: the Christian churches, their doctrines, constitutional forms and ways of worship. London: A. & R. Mowbray & Co. (first published in Norwegian in 1953 as Konfesjonskunnskap).

- Whalen, Brett Edward (2009). Dominion of God: Christendom and Apocalypse in the Middle Ages. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

External links

- Websites

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.