Marrakesh

Marrakesh

مراكش | |

|---|---|

|

UTC+1 (CET ) | |

| |

| Official name | Medina of Marrakesh |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv, v |

| Reference | 331 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

| Area | 1,107 ha |

Marrakesh or Marrakech (

The city was founded circa 1070 by

Marrakesh comprises an old fortified city packed with vendors and their stalls. This

Marrakesh is served by

Etymology

The exact meaning of the name is debated.

From medieval times until around the beginning of the 20th century, the entire country of Morocco was known as the "Kingdom of Marrakesh", as the kingdom's

History

The Marrakesh area was inhabited by Berber farmers from Neolithic times, and numerous stone implements have been unearthed in the area.[6] Marrakesh was founded by Abu Bakr ibn Umar, chieftain and second cousin of the Almoravid king Yusuf ibn Tashfin (c. 1061–1106).[16][17] Historical sources cite a variety of dates for this event ranging between 1062 (454 in the Hijri calendar), according to Ibn Abi Zar and Ibn Khaldun, and 1078 (470 AH), according to Muhammad al-Idrisi.[18] The date most commonly used by modern historians is 1070,[19] although 1062 is still cited by some writers.[20]

The Almoravids, a Berber dynasty seeking to reform Islamic society, ruled an

In 1125, the preacher

The death of

In the early 16th century, Marrakesh again became the capital of Morocco. After a period when it was the seat of the

For centuries Marrakesh has been known as the location of the tombs of Morocco's

During the early 20th century, Marrakesh underwent several years of unrest. After the premature death in 1900 of the grand vizier

Since the independence of Morocco, Marrakesh has thrived as a tourist destination. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the city became a trendy "

In the 21st century, property and real estate development in the city has boomed, with a dramatic increase in new hotels and shopping centres, fuelled by the policies of

Geography

The city is located in the

Climate

Marrakesh features a

Between 1961 and 1990 the city averaged 281.3 millimetres (11.1 in) of precipitation annually.

| Climate data for Marrakesh, Morocco ( Menara International Airport ) 1991–2020, extremes 1900–present

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

41.3 (106.3) |

44.4 (111.9) |

46.9 (116.4) |

49.6 (121.3) |

48.6 (119.5) |

44.8 (112.6) |

39.8 (103.6) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

49.6 (121.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

37.4 (99.3) |

32.5 (90.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.8 (78.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 25.0 (0.98) |

25.7 (1.01) |

35.2 (1.39) |

26.3 (1.04) |

10.5 (0.41) |

3.1 (0.12) |

2.2 (0.09) |

4.7 (0.19) |

15.2 (0.60) |

19.1 (0.75) |

29.8 (1.17) |

24.2 (0.95) |

221.0 (8.70) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.0 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 29.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%)

|

65 | 66 | 61 | 60 | 58 | 55 | 47 | 47 | 52 | 59 | 62 | 65 | 58 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 230.1 | 216.5 | 252.8 | 270.2 | 303.1 | 359.7 | 330.4 | 315.1 | 266.8 | 251.5 | 228.9 | 226.6 | 3,251.7 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1981–2010)[80][81] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (record highs for February, April, May, September and November, and humidity),[82] Meteo Climat (record highs and record lows for June, July and August only)[83] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Marrakesh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 12.1 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7.3 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[84] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

A 2019 paper published in PLOS One estimated that under Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, a "moderate" scenario of climate change where global warming reaches ~2.5–3 °C (4.5–5.4 °F) by 2100, the climate of Marrakesh in the year 2050 would most closely resemble the current climate of Bir Lehlou in Western Sahara. The annual temperature would increase by 2.9 °C (5.2 °F), and the temperature of the coldest month by 1.6 °C (2.9 °F), while the temperature of the warmest month would increase by 7 °C (13 °F).[85][86] According to Climate Action Tracker, the current warming trajectory appears consistent with 2.7 °C (4.9 °F), which closely matches RCP 4.5.[87]

Water

Marrakesh's water supply relies partly on groundwater resources, which have lowered gradually over the last 40 years, attaining an acute decline in the early 2000s. Since 2002, groundwater levels have dropped by an average of 0.9 m per year in 80% of Marrakesh and its surrounding area. The most affected area experienced a drop of 37 m (more than 2 m per year).[88]

Demographics

According to the 2014 census, the population of Marrakesh was 928,850 against 843,575 in 2004. The number of households in 2014 was 217,245 against 173,603 in 2004.[89][90]

Economy

Marrakesh is a vital component of the economy and culture of Morocco.

After the

Trade and crafts are extremely important to the local tourism-fueled economy. There are 18 souks in Marrakesh, employing over 40,000 people in pottery, copperware, leather and other crafts. The souks contain a massive range of items from plastic sandals to Palestinian-style scarves imported from India or China. Local boutiques are adept at making western-style clothes using Moroccan materials.[93] The Birmingham Post comments: "The souk offers an incredible shopping experience with a myriad of narrow winding streets that lead through a series of smaller markets clustered by trade. Through the squawking chaos of the poultry market, the gory fascination of the open-air butchers' shops and the uncountable number of small and specialist traders, just wandering around the streets can pass an entire day."[91] Marrakesh has several supermarkets including Marjane Acima, Asswak Salam and Carrefour, and three major shopping centres, Al Mazar Mall, Plaza Marrakech and Marjane Square; a branch of Carrefour opened in Al Mazar Mall in 2010.[102][103] Industrial production in the city is centred in the neighbourhood of Sidi Ghanem Al Massar, containing large factories, workshops, storage depots and showrooms. Ciments Morocco, a subsidiary of a major Italian cement firm, has a factory in Marrakech.[104]

Marrakesh is one of North Africa's largest centers of wildlife trade, despite the illegality of most of this trade.[105] Much of this trade can be found in the medina and adjacent squares. Tortoises are particularly popular for sale as pets, and Barbary macaques and snakes can also be seen.[106][107] The majority of these animals suffer from poor welfare conditions in these stalls.[108]

Politics

Marrakesh, the regional capital, constitutes a prefecture-level administrative unit of Morocco,

On 12 June 2009,

Since the legislative elections in November 2011, the ruling political party in Marrakesh has, for the first time, been the

Landmarks

Jemaa el-Fnaa

The Jemaa el-Fnaa is one of the best-known squares in Africa and is the centre of city activity and trade. It has been described as a "world-famous square", "a metaphorical urban icon, a bridge between the past and the present, the place where (spectacularized) Moroccan tradition encounters modernity."[116] It has been part of the UNESCO World Heritage site since 1985.[117] The square's name has several possible meanings; the most plausible etymology endorsed by historians is that it meant "ruined mosque" or "mosque of annihilation", referring to the construction of a mosque within the square in the late 16th century that was left unfinished and fell into ruin.[118][119][120] The square was originally an open space for markets located on the east side of the Ksar el-Hajjar, the main fortress and palace of the Almoravid dynasty who founded Marrakesh.[23][53]

Historically this square was used for public executions by rulers who sought to maintain their power by frightening the public. The square attracted dwellers from the surrounding desert and mountains to trade here, and stalls were raised in the square from early in its history. It drew tradesmen, snake charmers, dancing boys, and musicians playing

Souks

Marrakesh has the largest traditional market in Morocco and the image of the city is closely associated with its

The Medina is also famous for its street food. Mechoui Alley is particularly famous for selling slow-roasted lamb dishes.[125] The Ensemble Artisanal, located near the Koutoubia Mosque, is a government-run complex of small arts and crafts which offers a range of leather goods, textiles and carpets. Young apprentices are taught a range of crafts in the workshop at the back of this complex.[126]

City walls and gates

The ramparts of Marrakesh, which stretch for some 19 kilometres (12 mi) around the medina of the city, were built by the Almoravids in the 12th century as protective fortifications. The walls are made of a distinct orange-red clay and chalk, giving the city its nickname as the "red city"; they stand up to 19 feet (5.8 m) high and have 20 gates and 200 towers along them.[127]

Of the city's gates, one of the best-known is Bab Agnaou, built in the late 12th century by the Almohad caliph Ya'qub al-Mansur as the main public entrance to the new Kasbah.[128][129] The gate's carved floral ornamentation is framed by three panels marked with an inscription from the Quran in Maghrebi script using foliated Kufic letters.[130] The medina has at least eight main historic gates: Bab Doukkala, Bab el-Khemis, Bab ad-Debbagh, Bab Aylan, Bab Aghmat, Bab er-Robb, Bab el-Makhzen and Bab el-'Arissa. These date back to the 12th century during the Almoravid period and many of them have been modified since.[131][53]

Gardens

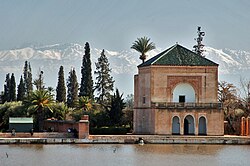

The city is home to a number of gardens, both historical and modern. The largest and oldest gardens in the city are the

The

The Koutoubia Mosque is also flanked by another set of gardens, the Koutoubia Gardens. They feature orange and palm trees, and are frequented by storks.[139] The Mamounia Gardens, more than 100 years old and named after Prince Moulay Mamoun, have olive and orange trees as well as a variety of floral displays.[140] In 2016,[141] at a location between the city and the Atlas Mountains, artist André Heller opened the ANIMA garden, which combines a diverse collection of plants with a display of works by famous artists such as Keith Haring and Pablo Picasso.[142] In the same year, a large restored riad garden set within a historical mansion, located inside the medina, was opened to visitors as Le Jardin Secret ('The Secret Garden').[142]

Palaces and Riads

The historic wealth of the city is manifested in palaces, mansions and other lavish residences. The best-known palaces today are the El Badi Palace and the Bahia Palace, as well as the main Royal Palace which is still in use as one of the official residences of the King of Morocco. Riads (Moroccan mansions, historically designating a type of garden[53]) are common in Marrakesh. Based on the design of the Roman villa, they are characterized by an open central garden courtyard surrounded by high walls. This construction provided the occupants with privacy and lowered the temperature within the building.[143] Numerous riads and historic residences exist through the old city, with the oldest documented examples dating back to the Saadian period (16th-17th centuries), while many others date from the 19th and 20th centuries.[45][53]

Mosques

The

Ben Youssef Mosque is named after the Almoravid sultan Ali ibn Yusuf, who built the original mosque in the 12th century to serve as the city's main Friday mosque.[148] After being abandoned during the Almohad period and falling into ruin, it was rebuilt in the 1560s by Abdallah al-Ghalib and then completely rebuilt again Moulay Sliman at the beginning of the 19th century.[149] The 16th-century Ben Youssef Madrasa is located next to it. Also next to it is the Almoravid Qubba, a rare architectural remnant of the Almoravid period which was excavated and restored in the 20th century. It is a domed kiosk that demonstrates a sophisticated style and is an important indication of the art and architecture of the period.[150][129]

The

Among the other notable mosques of the city is the 14th-century Ben Salah Mosque, located east of the medina centre. It is one of the only major Marinid-era monuments in the city.[155] The Mouassine Mosque (also known as the Al Ashraf Mosque) was built by the Saadian sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib between 1562–63 and 1572–73.[156] It was part of a larger architectural complex which included a library, hammam (public bathhouse), and a madrasa (school). The complex also included a large ornate street fountain known as the Mouassine Fountain, which still exists today.[156][157] The Bab Doukkala Mosque, built around the same time further west, has a similar layout and style as the Mouassine Mosque. Both the Mouassine and Bab Doukkala mosques appear to have been originally designed to anchor the development of new neighbourhoods after the relocation of the Jewish district from this area to the new mellah near the Kasbah.[156][158][159]

Tombs

One of the most famous funerary monuments in the city is the Saadian Tombs, which were built in the 16th century as a royal necropolis for the Saadian Dynasty. It is located next to the south wall of the Kasbah Mosque. The necropolis contains the tombs of many Saadian rulers including Muhammad al-Shaykh, Abdallah al-Ghalib, and Ahmad al-Mansur, as well as various family members and later sultans.[154] It consists of two main structures, each with several rooms, standing within a garden enclosure. The most important graves are marked by horizontal tombstones of finely carved marble, while others are merely covered in colorful zellij tiles. Al-Mansur's mausoleum chamber is especially rich in decoration, with a roof of carved and painted cedar wood supported on twelve columns of carrara marble, and with walls decorated with geometric patterns in zellij tilework and vegetal motifs in carved stucco. The chamber next to it, originally a prayer room equipped with a mihrab, was later repurposed as a mausoleum for members of the Alawi dynasty.[154][160]

The city also holds the tombs of many Sufi figures. Of these, there are

Mellah

The

Hotels

As one of the principal tourist cities in Africa, Marrakesh has over 400 hotels.

Culture

Museums

The Marrakech Museum, housed in the Dar Menebhi Palace in the old city centre, was built at the beginning of the 20th century by Mehdi Menebhi.[176][177] The palace was carefully restored by the Omar Benjelloun Foundation and converted into a museum in 1997.[178] The museum holds exhibits of both modern and traditional Moroccan art together with fine examples of historical books, coins and pottery produced by Moroccan Arab, Berber, and Jewish peoples.[179][180]

The Dar Si Said Museum is to the north of the Bahia Palace. It was the mansion of Si Said, brother to Grand Vizier Ba Ahmad, and was constructed in the same era as Ahmad's own Bahia Palace.[181][182] In the 1930s, during the French Protectorate period, it was converted into a museum of Moroccan art and woodcraft.[183] After recent renovations, the museum reopened in 2018 as the National Museum of Weaving and Carpets.[184][185]

The former home and villa of Jacques Majorelle, a blue-coloured building within the Majorelle Gardens, was converted into the Berber Museum (Musée Pierre Bergé des Arts Berbères) in 2011, after previously serving as a museum of Islamic art.[186][187][188] It exhibits a variety of objects of Amazigh (Berber) culture from across different regions of Morocco.[186]

The

Elsewhere in the medina, the Dar El Bacha hosts the Musée des Confluences, which opened in 2017.[194] The museum holds temporary exhibits highlighting different facets of Moroccan culture[195] as well as various art objects from different cultures across the world.[196] Various other small and often privately owned museums also exist, such as the Musée Boucharouite and the Perfume Museum (Musée du Parfum).[197][198][199] Dar Bellarj, an arts center located in a former mansion next to the Ben Youssef Mosque, also occasionally hosts art exhibits.[200][197] The Tiskiwin Museum is housed in another restored medina mansion and features a collection of artifacts from across the former the trans-Saharan trade routes.[201][202] A number of art galleries and museums are also found outside the medina, in Gueliz and its surrounding districts in the new city.[203][197]

Music, theatre and dance

Two types of music are traditionally associated with Marrakesh.

The Théâtre Royal de Marrakesh, the Institut Français and Dar Chérifa are major performing arts institutions in the city. The Théâtre Royal, built by Tunisian architect Charles Boccara, puts on theatrical performances of comedy, opera, and dance in Arabic and French.[206] A great number of storytellers, musicians and others also perform outdoor shows to entertain locals and tourists on the Jemaa el-Fnaa, especially at night.[207]

Crafts

The arts and crafts of Marrakesh have had a wide and enduring impact on Moroccan handicrafts to the present day. Riad décor is widely used in carpets and textiles, ceramics, woodwork, metal work and zelij. Carpets and textiles are weaved, sewn or embroidered, sometimes used for upholstering. Moroccan women who practice craftsmanship are known as Maalems (expert craftspeople) and make such fine products as Arabic and Berber carpets and shawls made of sabra (another name for rayon, also sometimes called cactus silk).[205][208][209] Ceramics are in varying styles in monochrome, a limited tradition depicting bold forms and decorations.[205]

Wood crafts are generally made of

Metalwork made in Marrakesh includes brass lamps, iron lanterns, candle holders made from recycled sardine tins, and engraved brass teapots and tea trays used in the traditional serving of tea. Contemporary art includes sculpture and figurative paintings. Blue veiled Tuareg figurines and calligraphy paintings are also popular.[205]

Festivals

Festivals, both national and Islamic, are celebrated in Marrakesh and throughout the country, and some of them are observed as national holidays.

Food

Surrounded by lemon, orange, and

Shrimp, chicken and lemon-filled

The desserts of Marrakesh include

The

Education

Marrakesh has several universities and schools, including

Ben Youssef Madrasa

The Ben Youssef Madrasa, north of the Medina, was an Islamic college in Marrakesh named after the Almoravid sultan Ali ibn Yusuf (1106–1142) who expanded the city and its influence considerably. It is the largest madrasa in all of Morocco and was one of the largest theological colleges in North Africa, at one time housing as many as 900 students.[231]

This education complex specialized in Quranic law and was linked to similar institutions in

Sports

Football clubs based in Marrakesh include

Golf is a popular sport in Marrakech. The city has three golf courses just outside the city limits and played almost through the year. The three main courses are the Golf de Amelikis on the road to Ourazazate, the Palmeraie Golf Palace near the Palmeraie, and the Royal Golf Club, the oldest of the three courses.[238]

Transport

Bus

BRT Marrakesh, a bus rapid transit system using trolleybuses was opened in 2017.[239]

Rail

The

Road

The main road network within and around Marrakesh is well paved. The major highway connecting Marrakesh with Casablanca to the north is the A7, a toll expressway, 210 km (130 mi) in length. The road from Marrakesh to

Air

The

Healthcare

Marrakesh has long been an important centre for healthcare in

A severe strain has been placed upon the healthcare facilities of the city in the last decade as the city population has grown dramatically.

In 2009, king Mohammed VI inaugurated a regional psychiatric hospital in Marrakesh, built by the Mohammed V Foundation for Solidarity, costing 22 million dirhams (approximately 2.7 million U.S. dollars).[249] The hospital has 194 beds, covering an area of 3 hectares (7.4 acres).[249] Mohammed VI has also announced plans for the construction of a 450 million dirham military hospital in Marrakesh.[250]

International relations

Marrakesh is twinned with:[251]

Notable people

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

- Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi, 13th-century mathematician and astronomer[252]

- 'Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi, 13th-century historian[253]

- Ibn 'Idhari, 13th/14th-century historian[254]

- Muhammad al-Ifrani, 17th/18th-century historian and biographer[255]

- Amine Amamou, footballer

- Abdelali Mhamdi, professional goalkeeper.

- Ahmed Bahja - Former footballer

- Hasna Benhassi - Former middle-distance runner

- Tahar El Khalej - Former footballer

- Abdellah Jlaidi - footballer

- Adil Ramzi - Former footballer

- Salaheddine Saidi - footballer

- Tahar Tamsamani - Former boxer

- Mordechai Vanunu - Israeli nuclear whistleblower (born in Marrakesh)

See also

- Arab Astronomical Society (2016)

- List of people from Marrakesh

- Marrakesh in popular culture

- Massira, Marrakech

References

- High Commission for Planning. 19 March 2015. p. 7. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ High Commission for Planning. 20 March 2015. p. 8. Archivedfrom the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Marrakech or Marrakesh". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ a b Shillington 2005, p. 948.

- ^ a b Nanjira 2010, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d e Searight 1999, p. 378.

- ^ Egginton & Pitz 2010, p. 11.

- ^ de Cenival 1991, p. 588.

- ^ Cornell 1998, p. 15.

- ^ RAE; RAE. "Marrakech | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas". «Diccionario panhispánico de dudas» (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ISBN 978-1-62616-331-7.

- ^ a b de Cenival 1991, p. 593.

- ^ a b Gottreich 2007, p. 10.

- ISBN 978-0-7397-1514-7. Archivedfrom the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ Rogerson & Lavington 2004, p. xi.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 59–64.

- ^ Gerteiny 1967, p. 28.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 61.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 59–63; Messier 2010, p. 180; Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 83; Salmon 2018, p. 33; Wilbaux 2001, p. 208; Bennison 2016, p. 22, 34; Lintz, Déléry & Tuil Leonetti 2014, p. 565.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, "Marrakesh"; Naylor 2009, p. 90; Park & Boum 2006, p. 238.

- ^ a b Bennison 2016.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 56–59.

- ^ a b Deverdun 1959, p. 143.

- ^ Skounti, Ahmed; Tebaa, Ouidad (2006). La Place Jemaa El Fna: patrimoine immatériel de Marrakech du Maroc et de l'humanité (in French). Rabat: Bureau de l’UNESCO pour le Maghreb. pp. 25–27. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 115.

- from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 292.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 85-87, 110.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 224.

- ^ Bennison 2016, p. 60, 70.

- ^ a b Bennison 2016, p. 307.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 241.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 224, 246.

- ^ Bennison 2016, p. 321, 343.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 243-244.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 246-247.

- ^ Bennison 2016, p. 265.

- ISSN 1873-9830.

- from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b de Cenival 1991, p. 592.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 358–416.

- ^ a b Salmon 2016.

- ^ de Cenival 1991, p. 594.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 460–461.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 392–401.

- ^ Salmon 2016, pp. 250–270.

- from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "The Patron Saints of Marrakech". Dar-Sirr.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ de Cenival 1991, p. 591.

- ^ a b c d e Wilbaux 2001.

- ^ Loizillon 2008, p. 50.

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica(1910).

- ISBN 978-90-04-23062-0. Archivedfrom the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Barrows 2004, p. 73.

- ^ a b Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Hoisington 2004, p. 109.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 38.

- ^ MEED. Economic East Economic Digest, Limited. 1971. p. 324. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b Sullivan 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b Howe 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Bigio 2012, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Shackley 2012, p. 43.

- ^ "Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization (with final act, annexes and protocol). Concluded at Marrakesh on 15 April 1994" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Academie de droit 2002, p. 71.

- ^ "Morocco: Marrakesh bomb strikes Djemaa el-Fna square". BBC. 28 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ "Qaeda denies involvement in Morocco cafe bomb attack". Reuters. 7 May 2011. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ "MARRAKECH: Dozens of heads of State and Government to attend UN climate conference". United Nations. 13 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Deadliest quake in decades leaves thousands dead in Morocco". France 24. 9 September 2023. Archived from the original on 9 September 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ "IMF, World Bank hold meetings in Morocco weeks after devastating quake". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2023-10-10. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- ^ "IMF Managing Director Arrives in Marrakech for Annual Meetings". HESPRESS English - Morocco News. 2023-10-07. Archived from the original on 2023-10-15. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- ^ Searight 1999, p. 407.

- ^ a b Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ Clark 2012, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b "Marrakech (Marrakesh) Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Barrows 2004, p. 74.

- ^ "Marrakech Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Marrakech / Marokko" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ "Station Menara" (in French). Météo Climat. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "Marrakesh, Morocco - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- PMID 31291249.

- ^ "Cities of the future: visualizing climate change to inspire action". Current vs. future cities. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "The CAT Thermometer". Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ISSN 2073-4441.

- ^ "2014 Morocco Population Census".

- ^ "Recensement général de la population et de l'habitat de 2004" (PDF). Haut-commissariat au Plan, Lavieeco.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ The Birmingham Post. 2 September 2006.[dead link]

- ^ a b Duncan, Fiona. "The best Marrakesh hotels". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Marrakech is the new Costa del Sol: for a host of Western celebrities, Marrakech in Morocco has become the place to be seen at and increasingly, to live in. Where celebrities go, the lesser folk are bound to follow. The result is that Morocco's economy and its culture is changing—but for the better or for the worse?". African Business. 1 March 2005.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Fatima Zahra Mansouri, première dame de Marrakech". Jeune Afrique (in French). 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ "La reprise de la croissance du secteur immobilier à Marrakech" (in French). Regiepresse.co. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Marrakech, Morocco Sees Hotel Boom". Huffington Post. 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- Mena Report. 2 October 2008. Archived from the originalon 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Mena Report. 13 April 2012. Archived from the originalon 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Humphrys 2010, p. 9.

- ISBN 978-3-8327-9233-6. Archivedfrom the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-84670-019-4.

- ^ Humphrys 2010, p. 161.

- ISBN 978-1-907065-30-9. Archivedfrom the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ "Nos usines et centres L'usine de Marrakech" (in French). Ciments du Maroc. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Bergin, Daniel; Nijman, Vincent (2014-11-01). "Open, Unregulated Trade in Wildlife in Morocco's Markets". ResearchGate. 26 (2). Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- ^ Nijman, Vincent; Bergin, Daniel; Lavieren, Els van (2015-07-01). "Barbary macaques exploited as photo-props in Marrakesh's punishment square". ResearchGate. Jul–Sep. Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- doi:10.1163/15685381-00003109. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2019-04-23.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 51967901. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2019-04-23.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "L'Organisation Judicaire" (in French). Le Ministère de la Justice. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "Adresses Utiles" (in French). Chambre de Commerce, D'Industrie et des Services de Marrakech. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Morocco's Marrakech elects first woman mayor". Al Arabiya (Saudi Arabia). 21 June 2009. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Biography of Fatima Zahra MANSOURI". African Success. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ "Women elected mayors of Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakesh |". AW. Archived from the original on 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ "Législatives 2011 – Marrakech: Grosse défaite pour les partis de la Koutla" (in French). L'Economiste. 28 November 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Législatives partielles: Marrakech: Le PJD garde son siège" (in French). L'Economiste. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Pons, Crang & Travlou 2009, p. 39.

- ^ a b Harrison 2012, p. 144.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 590–593.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 263.

- ^ Salmon 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Barrows 2004, pp. 76–78.

- from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, p. 148.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 51.

- ^ "Street Food of Marrakech Medina". Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ Jacobs 2013, p. 153.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Deverdun 1959.

- ^ a b c Salmon 2018.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 480.

- ^ Allain, Charles; Deverdun, Gaston (1957). "Les portes anciennes de Marrakech". Hespéris. 44: 85–126. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ^ a b "Qantara - The garden and the pavilion of the Menara". www.qantara-med.org. Archived from the original on 2021-08-31. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 246–247, 281–282.

- ^ "History". Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Davies 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, p. 146.

- ^ Marescaux, Patrick (21 April 2016). "Jardin Anima, l'extraordinaire rêve marrakchi d'un artiste autrichien". Médias24. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ a b Foreman, Liza (12 December 2017). "Preserving Morocco's grand gardens". BBC News. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ Davies 2009, p. 104.

- ISBN 978-0-19-531003-0. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 101.

- ISBN 0870996371.

- ^ Hattstein, Markus and Delius, Peter (eds.) Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 516.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 232–237.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 238.

- ^ Salmon 2016, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Salmon 2016, pp. 184–247.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 318-320.

- ^ a b c Salmon 2016, pp. 28–77.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, pp. 256–263.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, pp. 363–373.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, p. 189.

- ^ "The Patron Saints of Marrakech". Dar Sirr. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 574.

- ^ VorheesEdsall 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Gottreich 2003, p. 287.

- ^ a b Larson, Hilary (May 8, 2012). "The Marrakesh Express". The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Marrakech". International Jewish Cemetery Project. 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Jewish in Morocco". Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ Denby 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Layton 2011, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Sullivan 2006, p. 45.

- ^ a b Venison 2005, p. 214.

- ^ Davies 2009, p. 103.

- ^ "Palmeraie Rotana Resort Archived 2021-08-31 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Hudson, Christopher (20 March 2012). "Accor opens first Pullman hotel in Marrakech". Hotelier Middle East. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, pp. 290–291.

- ^ "Le quartier ibn Yūsuf". Bulletin du patrimoine de Marrakech et de sa région. March 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-08-31. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- ^ Mayhew & Dodd 2003, p. 341.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, p. 144.

- ^ "Musée de Marrakech: Fondation Omar Benjelloun" (in French). Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Wilbaux 2001, p. 289.

- ^ Deverdun 1959, p. 546.

- ^ "Musée Dar si Saïd de Marrakech". Fondation nationale des musées (in French). Archived from the original on 2017-12-19. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ^ "Ouverture du Musée National du Tissage et du Tapis Dar Si Saïd de Marrakech" (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ^ "Après rénovation, le Musée Dar Si Said de Marrakech rouvre ses portes". Médias24. 28 June 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ a b "The MUSÉE PIERRE BERGÉ DES ARTS BERBÈRES – Jardin Majorelle". www.jardinmajorelle.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-02-27.

- ^ "Majorelle Gardens". Archnet. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2021-02-27.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, p. 466.

- ^ "Maison de la Photographie | Marrakesh, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Maison de la photo à Marrakech: Voyage dans le voyage ! [Médina]". Vanupied (in French). 2018-05-11. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Musée de la Musique - Musée Mouassine à Marrakech". Vivre-Marrakech.com. Archived from the original on 2021-06-05. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ "Musee de Mouassine Marrakesh". MoMAA | African Modern Online Art Gallery & Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Le Musée de la Musique". Musée de la Musique (in French). 2020-10-08. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Le Matin - S.M. le Roi lance d'importants projets destinés à la préservation du patrimoine historique de l'ancienne médina de Marrakech et au renforcement de sa vocation touristique". Lematin.ma. Archived from the original on 2017-02-16. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Confluence Museum (Dar El Pacha) in Marrakech, an exhibition of Islamic art in Marrakech, an exhibition of historical and archaeological data in Marrakech". Visitmarrakech.com. Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Afrique, Asie, Amérique du Sud… au Musée des Confluences". L'Economiste (in French). 2018-11-12. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- ^ a b c "The Best Art Galleries in Marrakech". Planet Marrakech. 2018-01-13. Archived from the original on 2021-02-10. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Musée Boucharouite | Marrakesh, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Musée du Parfum | Marrakesh, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "Dar Bellarj | Marrakesh, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 2021-03-16. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ "HOME". Musée Tiskiwin. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Musée Tiskiwin | Marrakesh, Morocco Attractions". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Hill, Lauren Jade. "Discover This Flourishing Art Scene On Your Next Trip To Marrakech". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ Bing 2011, pp. 154–6.

- ^ a b c d e Bing 2011, pp. 154–156.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 134.

- ^ Ben Ismaïl, Ahmed. "Cultural space of Jemaa el-Fna Square". UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "WEAVING A STORY → Franklin Till". www.franklintill.com. Archived from the original on 2023-09-28. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ^ TRAVEL WEEKLY. Reed Business Information Limited. 2006. p. 93.

- ^ a b Aldosar 2007, p. 1245.

- ^ "Marrakech Folklore Days | Marrakech celebrating cultural heritage of world". Archived from the original on 2019-06-23. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Bing 2011, p. 25.

- ^ a b Humphrys 2010.

- ^ "History". Marrakech Biennale. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Radan, Silvia (13 April 2013). "A journey through Marrakech cuisine". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ "حكاية بنت الرماد!". الجزيرة الوثائقية (in Arabic). 2018-02-11. Archived from the original on 2021-11-10. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ Caldicott & Caldicott 2001, p. 153.

- ^ Mallos 2006, p. 253.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Koehler 2012, p. 32.

- The Telegraph. 19 March 2013. Archived from the originalon 2015-07-04. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ Humphrys 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Davies 2009, p. 62.

- ^ Ring, Salkin & Boda 1996, p. 468.

- ^ Gottreich 2007, p. 164.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, p. 71.

- ^ Arino, Hbid & Dads 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Casas, Solh & Hafez 1999, p. 74.

- ^ "The University". Cadi Ayyad University. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-2-271-05780-8.

- ^ Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 299.

- ^ a b Rogerson 2000, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Cheurfi 2007, p. 740.

- ^ Michelin 2001, p. 363.

- ^ Christiani 2009, p. 161.

- ^ Clammer 2009, p. 308.

- ^ "Grand Prix Hassan II". ATP Tour. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ Sullivan 2006, p. 175.

- ^ "Marrakech trolleybus route inaugurated". Metro Report International. Railway Gazette International. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020.

- ^ ISBN 9781902339764. Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Marrakech". Office National Des Aéroports. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "MenARA Airport General Information". World Aero Data.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Investment program 2011". Office National Des Aéroports. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Presentation RAK". Office National Des Aéroports. Archived from the original on 2013-06-08. Retrieved 2012-10-19.

- ^ Bennison 2016, p. 152.

- ^ a b Laet 1994, pp. 861–862.

- ^ The OPEC Fund for International Development. 9 February 2001. Archivedfrom the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- Agence Maghreb Arabe Presse (MAP). 28 April 2011. Archived from the originalon 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Agence Maghreb Arabe Presse (MAP). 7 September 2009. Archived from the originalon 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Agence Maghreb Arabe Presse (MAP). 25 September 2011. Archived from the originalon 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Investissement à Marrakech". amde.ma (in French). Agence Marocaine pour le Développement de l'Entreprise. 2016-09-05. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- OCLC 495469456.

- ISBN 978-0-292-76665-5.

- OCLC 495469525.

Bibliography

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-07-20. Retrieved 2021-10-30.

- Academie de droit (2002). Water Resources and International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-1864-6.

- Aldosar, Ali (2007). Middle East, western Asia, and northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761475712. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- Arino, O.; Hbid, M.L.; Dads, Ait (2006). Delay Differential Equations and Applications: Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute held in Marrakech, Morocco, 9–21 September 2002. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-3645-3. Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Barrows, David Prescott (2004). Berbers And Blacks: Impressions Of Morocco, Timbuktu And The Western Sudan. Kessinger Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4179-1742-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Bennison, Amira K. (2016). The Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748646821.

- Bigio, Anthony G. (2012). "Towards a Development Strategy for Morocco's Medinas". In Balbo, Marcello (ed.). The Medina: The Restoration and Conservation of Historic Islamic Cities. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78673-497-6.

- Bing, Alison (2011). Marrakesh Encounter. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74179-316-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture: Delhi to Mosque. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Caldicott, Chris; Caldicott, Carolyn (2001). The spice routes: chronicles and recipes from around the world. frances lincoln ltd. ISBN 978-0-7112-1756-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-11. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Casas, Joseph; Solh, Mahmoud; Hafez, Hala (1999). The National Agricultural Research Systems in West Asia and North Africa Region. ICARDA. p. 74. ISBN 978-92-9127-096-5.

- de Cenival, P. (1991). "Marrākus̲h̲". In ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Cheurfi, Achour (2007). L'encyclopédie maghrébine. Casbah éditions. ISBN 978-9961-64-641-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-14. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Christiani, Kerry (2009). Frommer's Marrakech Day by Day. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-71711-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Clammer, Paul (2009). Morocco. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-971-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Cornell, Vincent J. (1998). Realm of the Saint: Power and Authority in Moroccan Sufism. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71210-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Clark, Des (2012). Mountaineering in the Moroccan High Atlas. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84965-717-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Davies, Ethel (2009). North Africa: The Roman Coast. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-287-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Delbeke, M.; Schraven, M. (2011). Foundation, Dedication and Consecration in Early Modern Europe. BRILL. p. 185. ISBN 978-90-04-21757-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Denby, Elaine (2004). Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-121-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Deverdun, Gaston (1959). Marrakech: Des origines à 1912 (in French). Rabat: Éditions Techniques Nord-Africaines. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- Egginton, Jane; Pitz, Anne (2010). NG Spirallo Marrakech (in German). Mair Dumont Spirallo. ISBN 978-3-8297-3274-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Febvre, Lucien Paul Victor (1988). Annales. A. Colin. Archived from the original on 2015-11-05. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Gerteiny, Alfred G. (1967). Mauritania. Praeger.

- Gottreich, Emily (2003). "On the Origins of the Mellah of Marrakesh". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 35 (2). Cambridge University Press: 287–305. S2CID 162295018.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link - Gottreich, Emily (2007). The Mellah of Marrakesh: Jewish And Muslim Space in Morocco's Red City. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21863-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Hal, Fatéma (2002). Food of Morocco: Authentic Recipes from the North African Coast. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-962-593-992-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-01. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Hamilton, Richard (2011). The Last Storytellers: Tales from the Heart of Morocco. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-491-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Harrison, Rodney (2012). Heritage: Critical Approaches. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-26766-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Hoisington (2004). The Assassination of Jacques Lemaigre Dubreuil: A Frenchman between France and North Africa. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-35032-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Howe, Marvine (2005). Morocco: The Islamist Awakening and Other Challenges. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516963-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Humphrys, Darren (2010). Frommer's Morocco. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-56022-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Jacobs, Daniel (2013). The Rough Guide to Morocco. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-4093-3267-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Koehler, Jeff (2012). Morocco: A Culinary Journey with Recipes: A Culinary Journey with Recipes from the Spice-Scented Markets. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-1365-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Laet, Sigfried J. de (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Layton, Monique (2011). Notes from Elsewhere: Travel and Other Matters. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4620-3649-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Lehmann, Ingeborg; Henss, Rita; Szerelmy, Beate (2009). Baedeker Morocco. Baedeker. ISBN 978-3-8297-6623-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-04. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle, eds. (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne (in French). Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 9782350314907.

- Listri, Massimo; Rey, Daniel (2005). Marrakech: Living on the Edge of the Desert. Images Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86470-152-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Loizillon, Sophie (2008). Maroc (in French). Editions Marcus. ISBN 978-2-7131-0271-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Mallos, Tess (2006). A Little Taste Of-- Morocco. Murdoch Books. ISBN 978-1-74045-754-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Mayhew, Bradley; Dodd, Jan (2003). Morocco. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-361-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Michelin (2001). Morocco. Michelin Travel Publications. Archived from the original on 2015-11-05. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Messier, Ronald A. (2010). The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-38589-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Nanjira, Daniel Don (2010). African Foreign Policy and Diplomacy From Antiquity to the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37982-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Naylor, Phillip C. (2009). North Africa: A History from Antiquity to the Present. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71922-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar (2006). "Marrakech". Historical Dictionary of Morocco (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-8108-6511-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- Pons, Pau Obrador; Crang, Mike; Travlou, Penny (2009). Cultures of Mass Tourism: Doing the Mediterranean in the Age of Banal Mobilities. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-7213-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; Boda, Sharon La (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-03-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ISBN 978-1-900209-18-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2000). Marrakesh, Fez, Rabat. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-86011-973-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-22. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Searight, Susan (1999). Maverick Guide to Morocco. Pelican Publishing. p. 403. ISBN 978-1-56554-348-5.

- Shackley, Myra (2012). Atlas of Travel and Tourism Development. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-42782-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African history. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 9781579584542. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Sullivan, Paul (2006). A Hedonist's Guide to Marrakech. A Hedonist's guide to... ISBN 978-1-905428-06-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Tast, Brigitte (2020). Die rote Stadt; in: Brigitte Tast: Rot in Schwarz-Weiß, Schellerten, S. 47ff. ISBN 978-3-88842-605-6

- Venison, Peter J. (2005). In the Shadow of the Sun: Travels And Adventures in the World of Hotels. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-35458-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Vorhees, Mara; Edsall, Heidi (2005). Morocco. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-678-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Wilbaux, Quentin (2001). La médina de Marrakech: Formation des espaces urbains d'une ancienne capitale du Maroc. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2747523888.

- Salmon, Xavier (2016). Marrakech: Splendeurs saadiennes: 1550-1650. Paris: LienArt. ISBN 9782359061826.

- Salmon, Xavier (2018). Maroc Almoravide et Almohade: Architecture et décors au temps des conquérants, 1055-1269. Paris: LienArt.

Further reading

- Fernea, Elizabeth Warnock (1988). A Street in Marrakech: A Personal View of Urban Women in Morocco. Waveland Press. ISBN 978-0-88133-404-3.

- Mourad, Khireddine (1994). Marrakech Et La Mamounia (in French). www.acr-edition.com. ISBN 978-2-86770-081-1.

- Wilbaux, Quentin (2009). Marrakesh: The Secret of Courtyard Houses. Translated by McElhearn, Kirk. ACR Édition. ISBN 978-2-86770-130-6.

External links

- Moroccan National Tourist Office Archived 2018-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Bulletin du Patrimoine – Patrimoines de Marrakech Archived 2023-10-23 at the Wayback Machine: local publication (in French) on the city's historic heritage, also available on Academia Archived 2023-10-23 at the Wayback Machine