Flora of Madagascar

The flora of Madagascar consists of more than 12,000

After its continental separation, Madagascar probably experienced a dry period, and

The first human presence in Madagascar dates only 2000–4000 years back, and settlement in the interior occurred centuries later. The

Human population growth and economic activity have put pressure on natural vegetation in the region, especially through

Diversity and endemism

Madagascar has been described as "one of the most floristically unique places in the world".

Vascular plants

Among the non-flowering plants, ferns, lycophytes and allies count roughly 570 described species in Madagascar. About half of these are endemic; in the scaly tree fern family Cyatheaceae, native to the humid forests, all but three of 47 species are endemic. Six conifers in genus Podocarpus – all endemic – and one cycad (Cycas thouarsii), are native to the island.[2]

In the

Other large monocot families include the Pandanaceae with 88 endemic pandan (Pandanus) species, mainly found in humid to wet habitats, and the Asphodelaceae, with most species and over 130 endemics in the succulent genus Aloe. Grasses (Poaceae, around 550 species[6]) and sedges (Cyperaceae, around 300) are species-rich, but have lower levels of endemism (40%[6] and 37%, respectively). The endemic traveller's tree (Ravenala madagascariensis), a national emblem and widely planted, is the sole Madagascan species in the family Strelitziaceae.[2]

The eudicots account for most of Madagascar's plant diversity. Their most species-rich families on the island are:[2]

- Fabaceae (legumes, 662 species – 77% endemic), accounting for many trees in humid and dry forests, including rosewood;

- Rubiaceae (coffee family, 632 – 92%), with notably over 100 endemic Psychotria and 60 endemic Coffea species;

- Asteraceae (composite family, 535 – 81%), with over 100 endemic species in Helichrysum;

- Acanthaceae (acanthus family, 500 – 94%), with 90 endemic species in Hypoestes;

- Euphorbiaceae (spurge family, 459 – 94%), notably the large genera Croton and Euphorbia;

- Malvaceae (mallows, 486 – 87%), including the large genus Dombeya (177 – 97%) and seven out of nine baobabs (Adansonia), of which six are endemic;

- Apocynaceae (dogbane family, 363 – 93%), including the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus);

- Melastomataceae (melastomes, 341 – 98%), mainly trees and shrubs.

Non-vascular plants

A checklist from 2012 records 751

Fungi

Many undescribed species of

Over 500 species of

Algae

Vegetation types

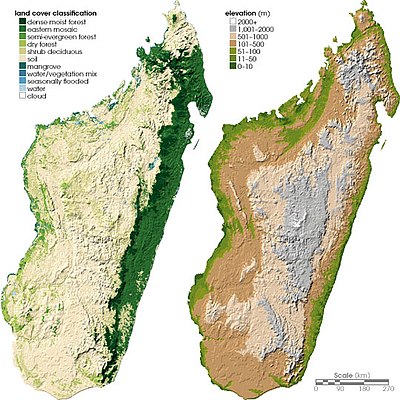

Land cover according to the Atlas of the vegetation of Madagascar (2007)[13]

Madagascar features contrasting and unique

The marked east–central–west distinction among Madagascan flora was already described by the English naturalist

Humid forests

Degraded humid forest (savoka in Malagasy) covers about ten percent of the island. It spans various states of degradation and is composed of forest remnants and planted or otherwise introduced species. It is primarily the result of slash-and-burn cultivation in primary forest. Some forest fragments still harbour a considerable amount of biodiversity.[13]

Littoral forest, found in several isolated areas along the eastern coast, covers less than 1% of the land area, on mainly sandy sediments. Climate is humid, with 1,300–3,200 mm (51–126 in) annual rainfall. Littoral forest covers sandy soil forest, marsh forest, and grasslands. Its flora includes various tree families, lianas, and

An isolated area of humid forest in the south west, on the eastern slope of the Analavelona massif, is classified as "Western humid forest" by the Atlas. It occurs on lavas and sand, at 700–1,300 m (2,300–4,300 ft) elevation. The forest is maintained through condensating moisture from ascending air. It is unprotected but the local population considers it sacred.[13] The WWF includes it in the "sub-humid forests" ecoregion.[17]

Dry forests and thicket

Dry forest, accounting for roughly 5% of the surface, is found in the west, from the northern tip of the island to the

"Western sub-humid forest" occurs inland in the southwest and covers less than 1% of the surface, mainly on sandstone, at 70–100 m (230–330 ft) elevation. Climate is sub-humid to sub-arid, with 600–1,200 mm (24–47 in) annual rainfall. The vegetation, up to 20 m tall (66 ft) with a closed canopy, includes diverse trees with many endemics such as baobabs (Adansonia), Givotia madagascariensis, and the palm Ravenea madagascariensis. Cutting, clearing and invasive species such as opuntias and agaves threaten this vegetation type.[13] It is part of the WWF's "sub-humid forests" ecoregion.[17]

The driest part of Madagascar in the southwest features the unique "

Grassland, woodland, and bushland

Grasslands dominate a large part of Madagascar, more than 75% according to some authors.[23] Mainly found on the central and western plateaus, they are dominated by C4 grasses such as the common Aristida rufescens and Loudetia simplex and burn regularly. While many authors interpret them as the result of human degradation through tree-felling, cattle raising and intentional burning, it has been suggested that at least some of the grasslands may be primary vegetation.[23][6] Grassland is often found in a mixture with trees or shrubs, including exotic pine, eucalypt, and cypress.[13]

The Atlas distinguishes a "wooded grassland–bushland mosaic" covering 23% of the surface and a "plateau grassland–wooded grassland mosaic" covering 42%. Both occur on various substrates and account for most of the WWF's "sub-humid forests" ecoregion.

An evergreen open forest or woodland type, tapia forest, is found on the western and central plateaus, at altitudes of 500–1,800 m (1,600–5,900 ft). It is dominated by the eponymous tapia tree (Uapaca bojeri) and covers less than 1% of the surface. The broad regional climate is sub-humid to sub-arid, but tapia forest is mainly found in drier microclimates. Trees other than tapia include the endemic Asteropeiaceae and Sarcolaenaceae, with a herbaceous understory. Tapia forest is subject to human pressure, but relatively well adapted to fire.[13] It falls in the WWF's "sub-humid forests" ecoregion.[17]

Wetlands

Marshes,

Origins and evolution

Paleogeography

Madagascar's high species richness and endemicity are attributed to its long isolation as a

After their separation from Africa, Madagascar and India moved northwards, to a position south of 30° latitude. During the

Species evolution

Several hypotheses exist as to how plants and other organisms have diversified into so many species in Madagascar. They mainly assume either that species diverged in parapatry by gradually adapting to different environmental conditions on the island, for example dry versus humid, or lowland versus montane habitats, or that barriers such as large rivers, mountain ranges, or open land between forest fragments, favoured allopatric speciation.[28] A Madagascan lineage of Euphorbia occurs across the island, but some species evolved succulent leaves, stems and tubers in adaptation to arid conditions.[29] In contrast, endemic tree ferns (Cyathea) all evolved under very similar conditions in Madagascan humid forests, through three recent radiations in the Pliocene.[30]

Exploration and documentation

Early naturalists

Madagascar and its natural history remained relatively unknown outside the island before the 17th century. Its only overseas connections were occasional Arab, Portuguese, Dutch, and English sailors, who brought home anecdotes and tales about the fabulous nature of Madagascar.

19th to 20th century

French naturalist Alfred Grandidier was a preeminent 19th-century authority on Malagasy wildlife. His first visit in 1865 was followed by several other expeditions. He produced an atlas of the island and, in 1885, published L'Histoire physique, naturelle et politique de Madagascar, which would comprise 39 volumes.[43] Although his main contributions were in zoology, he was also a prolific plant collector; several plants were named after him, including Grandidier's baobab (Adansonia grandidieri) and the endemic succulent genus Didierea.[36]: 185–187 The British missionary and naturalist Richard Baron, Grandidier's contemporary, lived in Madagascar from 1872 to 1907 where he also collected plants and discovered up to 1,000 new species;[44] many of his specimens were described by Kew botanist John Gilbert Baker.[14] Baron was the first to catalogue Madagascar's vascular flora in his Compendium des plantes malgaches, including over 4,700 species and varieties known at that time.[44]

During the

Research in the 21st century

Today, national and international research institutions are documenting the flora of Madagascar. The

Outside the country, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is one of the leading institutions in the revision of Madagascar's plant families; it also maintains the

Human impact

Madagascar was colonised rather recently compared to other landmasses, with first evidence for humans – arrived from either Africa or Asia – dating to 2,300

Uses of native species

The native flora of Madagascar has been and still is used for a variety of purposes by the

The traveller's tree has various uses in the east of Madagascar, chiefly as building material.[57] Madagascar's national instrument valiha is made from bamboo and lent its name to the endemic genus Valiha.[58] Yams (Dioscorea) in Madagascar include introduced, widely cultivated species as well as some 30 endemics, all edible.[59] Edible mushrooms, including endemic species, are collected and sold locally (see above, Diversity and endemism: Non-vascular plants and fungi).[8]

Many native plant species are used as herbal remedies for a variety of afflictions. An

Agriculture

One of the characteristic features of agriculture in Madagascar is the widespread cultivation of

Other major crops, such as

Forestry in Madagascar involves many exotic species such as eucalypts, pines and acacias.[66] The traditional slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy), practised for centuries, today accelerates the loss of primary forests as populations grow[69] (see below, Threats and conservation).

Introduced plants

More than 1,300

A prickly pear cactus,

The prickly pear illustrates the dilemma of plant introductions: while many authors see exotic plants as a threat to the native flora,[13][71] others argue that they have not yet been linked directly to the extinction of a native species, and that some may actually provide economic or ecological benefits.[66] A number of plants native to Madagascar have become invasive in other regions, such as the traveller's tree in Réunion and the flamboyant tree (Delonix regia) in various tropical countries.[71]

Threats and conservation

Madagascar, together with its neighbouring islands, is considered a

Rapid human population increase and economic activity entail

Conservation of natural habitats in Madagascar is concentrated in over six million hectares (23,000 sq mi) – about ten percent of the total land surface – of

References

- ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Catalogue of the plants of Madagascar". Saint Louis, Antananarivo: Missouri Botanical Garden. 2018. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- S2CID 220980697.

- ISBN 2-903700-04-4.

- ISBN 978-1-84246-182-2.

- ^ PMID 26791612.

- S2CID 85160063.

- ^ S2CID 39119949.

- (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2017.

- PMID 25719857.

- ISSN 0511-9618.

- ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ ISBN 9781842461983.

- ^ ISSN 0368-2927.

- ISBN 1-56098-683-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 November 2016.

- ^ S2CID 67777752.

- ^ ISBN 978-0226303079.

- JSTOR 2398861.

- S2CID 86348857. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 October 2020.

- ^ .

- PMID 19500874. Archived from the original(PDF) on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- PMID 24852061.

- S2CID 33039024.

- ISSN 0024-4074.

- PMID 17698810.

- PMID 27071108.

- PMID 27383816.

- ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ ISBN 978-1900347181.

- ISSN 1355-4905.

- ^ Morel, J.-P. (2002). "Philibert Commerson à Madagascar et à Bourbon" (PDF) (in French). Jean-Paul Morel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Tropicos – Ravenala madagascariensis Sonn". Saint Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden. 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- OCLC 175296918.

- ^ JSTOR 1221349.

- OCLC 459827227.

- OCLC 691006805.

- ^ a b "Le muséum à Madagascar" (PDF) (in French). Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Herbier du Parc Botanique et Zoologique de Tsimbazaza, Global Plants on JSTOR". New York: ITHAKA. 2000–2016. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Herbier du FO.FI.FA, Global Plants on JSTOR". New York: ITHAKA. 2000–2017. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Université d'Antananarivo – Départements & Laboratoires" (in French). Université d'Antananarivo. 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Madagascar – Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew". Richmond, Surrey: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Madagascar". St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden. 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ PMID 15288523.

- ISSN 1631-0683.

- ISSN 0277-3791.

- JSTOR 4118422.

- PMID 25027625.

- ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ISSN 2429-6422.

- PMID 24188563.

- PMID 1434686.

- JSTOR 4313756.

- ^ JSTOR 219188.

- ^ S2CID 55763047.

- ^ PMID 27247383.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2016.

- ISBN 0-521-83935-1. Archivedfrom the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ "FAOSTAT crop data by country, 2014". Food and Agriculture Organization. 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ ISBN 978-0226303079. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ISBN 978-0226303079.

- (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2018.

- ^ Conservation International (2007). "Madagascar and the Indian Ocean islands". Biodiversity Hotspots. Conservation International. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Groupe des Spécialistes des Plantes de Madagascar (2011). Liste rouge des plantes vasculaires endémiques de Madagascar (PDF) (in French). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2018.

- (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2018.

- ^ Butler, R. (2010). "Madagascar's political chaos threatens conservation gains". Yale Environment 360. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84246-647-6. Archived(PDF) from the original on 12 February 2018.

- ^ PMID 18664414.

- ^ "Madagascar's protected area surface tripled". World Wildlife Fund for Nature. 2013. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Endangered plant propagation program at Parc Ivoloina". Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

External links