Homo naledi

| Homo naledi | |

|---|---|

| |

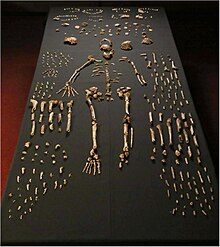

| The 737 known elements of H. naledi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. naledi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo naledi Berger et al., 2015 | |

| |

| Location of Rising Star Cave in the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa | |

Homo naledi is an

Along with similarities to contemporary Homo, they share several characteristics with the ancestral Australopithecus as well as early Homo (mosaic evolution), most notably a small cranial capacity of 465–610 cm3 (28.4–37.2 cu in), compared with 1,270–1,330 cm3 (78–81 cu in) in modern humans. They are estimated to have averaged 143.6 cm (4 ft 9 in) in height and 39.7 kg (88 lb) in weight, yielding a small encephalization quotient of 4.5. H. naledi brain anatomy seems to have been similar to contemporary Homo, which could indicate comparable cognitive complexity. The persistence of small-brained humans for so long in the midst of bigger-brained contemporaries revises the previous conception that a larger brain would necessarily lead to an evolutionary advantage, and their mosaic anatomy greatly expands the known range of variation for the genus.

H. naledi anatomy indicates that, though they were capable of long-distance travel with a humanlike stride and gait, they were more

Discovery

million years ago ) |

On 13 September 2013 while exploring the

The chamber had been entered at least once before, by cavers in the early 1990s. They rearranged some bones and may have caused further damage, although much of the floor in the chamber had not been walked on prior to 2013.[4] It lies about 80 m (260 ft) from the main entrance, at the bottom of a 12 m (39 ft) vertical drop, and the 10 m (33 ft) long main passage is only 25–50 cm (10 in – 1 ft 8 in) at its narrowest.[4] In total, more than 1,550 pieces of bone belonging to at least fifteen individuals (9 immature and 6 adults)[5] have been recovered from the clay-rich sediments. Berger and colleagues published the findings in 2015.[6]

The fossils represent 737 anatomical elements – including portions of the skull, jaw, ribs, teeth, limbs, and inner ear bones – from old, adult, young, and infantile individuals. There are also some

The

The remains of at least three additional individuals (two adults and a child) were reported in the Lesedi Chamber of the cave by John Hawks and colleagues in 2017.[7]

Classification

In 2017, the Dinaledi remains were dated to 335,000–236,000 years ago in the

The ability of such a small-brained hominin to have survived for so long in the midst of bigger-brained Homo greatly revises previous conceptions of human evolution and the notion that a larger brain would necessarily lead to an evolutionary advantage.[10] Their mosaic anatomy also greatly expands the range of variation for the genus.[12]

H. naledi is hypothesised to have branched off very early from contemporaneous Homo. It is unclear whether they branched off at around the time of

It is unclear if these H. naledi were an isolated population in the Cradle of Humankind, or if they ranged across Africa. If the latter, then several gracile hominin fossils across Africa which have traditionally been classified as late H. erectus could potentially represent H. naledi specimens.[13]

Anatomy

Skull

Two male H. naledi skulls from the Dinaledi chamber had cranial volumes of about 560 cm3 (34 cu in), and two female skulls 465 cm3 (28.4 cu in). A male H. naledi skull from the Lesedi chamber had a cranial volume of 610 cm3 (37 cu in). The Dinaledi specimens are more similar to the cranial capacity of australopithecines. For comparison, H. erectus averaged about 900 cm3 (55 cu in),

The skull shape is more similar to Homo, with a slenderer shape, the presence of temporal and occipital lobes of the brain, and reduced post-orbital constriction, with the skull not becoming narrower behind the eye-sockets.[6][16] The frontal lobe morphology is more or less the same in all Homo brains despite size, and differs from Australopithecus, which has been implicated in the production of tools, the development of language, and sociality.[16]

Like modern humans, but unlike fossil hominins, including South African australopithecines, H. erectus, and Neanderthals, the permanent 2nd molar erupted comparatively late in life, emerging alongside the premolars instead of before, which indicates a slower maturation unusually comparable to modern humans.[17] The tooth formation rate of the front teeth is also most similar to modern humans.[18] The overall size and shape of the molars most closely resemble those of three unidentified Homo specimens from the local Swartkrans and East African Koobi Fora Caves, and are similar in size (but not shape) to Pleistocene H. sapiens. The necks of the molars are proportionally similar to those of A. afarensis and Paranthropus.[19]

Unlike modern humans and contemporary Homo, H. naledi lacks several accessory dental features, and has a high frequency of individuals who present main

The anvil (a middle ear bone) more resembles those of chimps, gorillas, and Paranthropus than Homo.[21] Like H. habilis and H. erectus, H. naledi has a well-developed brow-ridge with a fissure stretching across just above the ridge, and like H. erectus a pronounced occipital bun. H. naledi has some facial similarities with H. rudolfensis.[20]

Build

The H. naledi specimens are estimated to have, on average, stood around 143.6 cm (4 ft 9 in) and weighed 39.7 kg (88 lb). This body mass is intermediate between what is typically seen in Australopithecus and Homo species. Like other Homo, male and female H. naledi were likely about the same size, males on average about 20% larger than females.

Concerning the

The shoulders are more similar to those of australopithecines, with the

Limbs

The

The metacarpals of the other fingers share adaptations with modern humans and Neanderthals to be able to cup and manipulate objects, and the

H. naledi was a

Pathology

The adult right

Dental defects in H. naledi specimens during 1.6–2.8 and 4.3–7.6 months of development were most likely caused by seasonal stressors. This may have been due to extreme summer and winter temperatures causing food scarcity. Minimum winter temperatures of the area average about 3 °C (37 °F), and can drop below freezing. Staying warm for an infant of the small-bodied H. naledi would have been difficult, and winters likely increased susceptibility to respiratory diseases. Environmental stressors are consistent with present-day

Local hominins were likely preyed upon by large carnivores, such as lions, leopards, and hyaenas. There seems to be a distinct paucity of large carnivore remains from the northern end of the Cradle of Humankind, where Rising Star Cave is located, possibly because carnivores preferred the Blaaubank River to the south which may have offered better hunting grounds with a greater abundance of large prey items. Alternatively, because many more sites are known in the south than the north, carnivore spatial patterns may not be well-represented by the fossil record (

Culture

Food

Dental chipping and wearing indicates the habitual consumption of small hard objects, such as dirt and dust, and cup-shaped wearing on the back teeth may have stemmed from gritty particles. These could have originated from unwashed roots and tubers. Alternatively, aridity could have stirred up particulates onto food items, coating food in dust. It is possible that they commonly ate larger hard items, such as seeds and nuts, but these were processed into smaller pieces before consumption.[31][32]

H. naledi occupied a seemingly unique niche from previous South African hominins, including Australopithecus and Paranthropus. The teeth of all three species indicate that they needed to exert high shearing force to chew through perhaps plant or muscle fibres. The teeth of other Homo cannot produce such high forces perhaps due to the use of some food processing techniques, such as cooking.[31]

Technology

H. naledi could have produced

Funerals

In 2015, archaeologist Paul Dirks, Berger, and colleagues concluded that the bodies had to have been deliberately carried and placed into the chamber by people because they appear to have been intact when they were first deposited in the chamber. There is no evidence of trauma from being dropped into the chamber nor of predation, and there is exceptional preservation. The chamber is inaccessible to large predators, appears to be an isolated system, and has never been flooded. That is, natural forces were not at play.[4]

There is no hidden shaft through which people could have accidentally fallen in, and there is no evidence of some catastrophe which killed all the individuals inside the chamber. They said it is possible that the bodies were dropped down a chute and fell slowly due to irregularity and narrowness of the path down, or a soft mud cushion to land on. In whatever scenario, the morticians would have required artificial light to navigate the cave. The site was used repeatedly for burials as the bodies were not all deposited at the same time.[4]

In 2016, palaeoanthropologist Aurore Val countered that such preservation may have been due to

In 2017, Dirks, Berger, and colleagues reaffirmed that there is no evidence of water flow into the cave, and that it is more likely that the bodies were deliberately deposited into the chamber. They said it is possible that they were deposited by contemporary Homo, such as the ancestors of modern humans, rather than other H. naledi, but that the cultural behaviour of funerary practises is not impossible for H. naledi. They proposed that placement in the chamber may have been done to remove decaying bodies from a settlement, prevent scavengers, or as a consequence of social bonding and grief.[10]

In 2018, anthropologist Charles Egeland and colleagues echoed Val's sentiments, and stated that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that a hominid species had developed a concept of the afterlife so early in time. They said that the preservation of the Dinaledi individuals is similar to those of baboon carcasses which accumulate in caves, either by natural death of cave-dwelling baboons, or by a leopard dragging in carcasses.[34]

In 2021, following the analysis of the bone fragments of an immature individual, Juliet Brophy and Berger again stated that the H. naledi remains were purposefully interred by some human species.[35] This would make Homo naledi the oldest evidence of burial by hominids.[36] The findings are disputed.[37]

Gallery

-

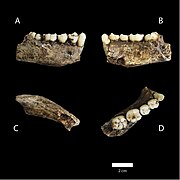

(A,B) Digitally reconstructed

skull sides -

Lower jaws of

LES1 (left) and DH1 (right) -

Upper jaws of

LES1 (left) and DH1 (right) -

(A,B,C,D) Views of one lower jaw

-

Views of one clavicle

-

Views of one humerus

-

Views of one ulna

-

Metacarpalsfrom several individuals, each labeled

-

Views of a 10ththoracic vertebra

-

Views of an 11ththoracic vertebra

-

Views of one femur

-

(A,B,C,D) Views of one tibia

-

Ankle bonesfrom several individuals, each labeled

-

(1) adult right foot, (2) juvenile left, (3,4) adult left, (5) juvenile right

See also

- African archaeology

- Australopithecus sediba – Two-million-year-old hominin from the Cradle of Humankind

- Denisovan – Asian archaic human

- Homo luzonensis – Archaic human from Luzon, Philippines

- Homo floresiensis – Archaic human from Flores, Indonesia

- Neanderthal – Extinct Eurasian species or subspecies of archaic humans

- Timeline of human evolution

References

- ^ PMID 28483040.

- ^ a b Tucker, Steven (13 November 2013). "Rising Star Expedition". Speleological Exploration Club. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ doi:10.1511/2016.121.198. Archived from the originalon 16 May 2017.

- ^ PMID 26354289.

- .

- ^ PMID 26354291.

- ^ PMID 28483039.

- PMID 27457542.

- .

- ^ PMID 28483041.

- S2CID 4469009.

- ^ PMID 27836166.

- PMID 26354290.

- S2CID 21705705.

- ^ PMID 28874266.

- ^ PMID 29760068.

- PMID 26914367.

- S2CID 14006736.

- S2CID 109058795.

- ^ PMID 29887210.

- S2CID 51618301.

- PMID 32236122.

- ^ PMID 28094004.

- S2CID 2909448.

- ^ PMID 27855981.

- ^ PMID 26441219.

- PMID 26439101.

- S2CID 29150977.

- .

- ^ Reynolds, S. C. (2010). "Where the Wild Things Were: Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Carnivores in the Cradle of Humankind (Gauteng, South Africa) in Relation to the Accumulation of Mammalian and Hominin Assemblages". Journal of Taphonomy. 8 (2–3): 233–257.[unreliable source?]

- ^ PMID 29606200.

- S2CID 24296825.

- PMID 27039664.

- PMID 29610322.

- .

- ^ Davis, Josh (5 June 2023). "Claims that ancient hominins buried their dead could alter our understanding of human evolution".

- S2CID 260201327.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-1-4262-1811-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4262-2388-4.

External links

- Reconstructions of H. naledi by palaeoartist John Gurche

- Wheeler, Sharon. "Dispatches from one of caving's Rising Stars". Darkness Below.

- "Prominent hominid fossils". Talk Origins.

- "Exploring the hominid fossil record". Bradshaw Foundation.

- "blog of Rising Star Expedition members". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015.

- "Three-dimensional scans of Homo naledi fossils". MorphoSource.

- "Human Timeline (Interactive)". National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian.