Ormus

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Kingdom of Ormus هرمز | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century–1622 | |||||||

|

Flag | |||||||

| |||||||

| Status |

| ||||||

| Capital | 27°06′N 56°27′E / 27.100°N 56.450°E | ||||||

| Common languages | Persian, Arabic | ||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||

| Government | Kingdom | ||||||

| King | |||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 11th century | ||||||

| 1622 | |||||||

| |||||||

The Kingdom of Ormus (also known as Hormoz or Hormuz;

The monarchy received its name from the fortified port city which served as its capital.[

Etymology

Popular etymology derives "Hormuz", being the

Old Hormuz

The original city of Hormoz was situated on the mainland in the province of Mogostan (Mughistan) near modern-day

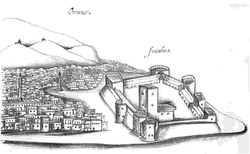

New Hormuz

"It was during the reign of Mir Bahrudin Ayaz Seyfin, fifteenth king of Hormoz, that the

Risso writes: "In the eleventh century, Saljûq Persia developed at the expense of what was left of Buwayhid Mesopotamia and the Saljûqs controlled ‘Umânî ports from about 1065 to 1140.

Abbé T G F Raynal gives the following account of Hormoz in his history: Hormoz became the capital of an empire which comprehended a considerable part of Arabia on one side, and Persia on the other. At the time of the arrival of the foreign merchants, it afforded a more splendid and agreeable scene than any city in the East. Persons from all parts of the globe exchanged their commodities and transacted their business with an air of politeness and attention, which are seldom seen in other places of trade. The streets were covered with mats and in some places with carpet, and the linen awnings which were suspended from the tops of the houses, prevented any inconvenience from the heat of the sun. India cabinets ornamented with gilded vases, or china filled with flowering shrubs or aromatic plants adorned their apartments. Camels laden with water were stationed in the public squares. Persian wines, perfumes, and all the delicacies of the table were furnished in great abundance, and they had the music of the East in its highest perfection ... In short, universal opulence, an extensive commerce, politeness in the men and gallantry in the women, united all their attractions to make this city the seat of pleasure.[10]

Hormuz enjoyed a long period of autonomy under the suzerainty of kings of Iran from the foundation of the kingdom in the 11th century to the coming of the Portuguese.

In the early 15th century, Hormuz was one the kingdoms that was visited by the Chinese expeditionary fleet commanded by Admiral Zheng He during the Ming treasure voyages and was the final destination of the fleet during the fourth voyage.[12][13] Ma Huan, an interpreter serving in the crew, described Hormuz society in a positive light in the Yingya Shenglan, writing for example about the people that "the limbs and faces of the people are refined and fair [...] and they are stalwart and fine-looking; their clothing and hats are handsome, distinctive and elegant."[13] Fei Xin, another crew member, made an account of Hormuz in the Xingcha Shenglan.[13] It included, for instance, observations suggesting that Hormuz society had a high standard of living, writing that "the lower classes are wealthy", and on local dressing habits such as the long robes worn by both men and women, the veils that women wore over their head and face when going out, and the jewels worn by the well-to-do.[13]

Portuguese conquest

In September 1507, the Portuguese

As

The kings of Hormuz under Portuguese rule were reduced to vassals of the Portuguese empire in India, mostly controlled from Goa. The archive of correspondence between the kings and local rulers of Hormuz,[20] and some of its governors and people, and the kings of Portugal, contain the details of the kingdom's disintegration and the independence of its various parts. They show the attempts by rulers such as Kamal ud-Din Rashed trying to gain separate favour with the Portuguese in order to guarantee their own power.[21] This reflects in the gradual independence of Muscat, previously a dependency of Hormuz, and its rise one of the successor states to Hormuz.

After the Portuguese made several abortive attempts to seize control of Basra, the

In the mid-17th century it was captured by the

Accounts of Ormus society

Situated between the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, Ormus was a "by-word for wealth and luxury",[22] perhaps best captured in the Arab saying: "If all the world were a golden ring, Ormus would be the jewel in it".[22] The city was also known for its licentiousness according to accounts by Portuguese visitors; Duarte Barbosa, one of the first Portuguese to travel to Ormuz in the early 16th century found:

The merchants of this isle and city are Persians and Arabs. The Persians [speak Arabic and another language which they call Psa[23]], are tall and well-looking, and a fine and up-standing folk, both men and women; they are stout and comfortable. They hold the creed of Muhammad in great honour. They indulge themselves greatly, so much so that they keep among them youths for the purpose of abominable wickedness. They are musicians, and have instruments of diverse kinds. [24]

This theme is also strong in

Its moral state was enormously and infamously bad. It was the home of the foulest sensuality, and of all the most corrupted forms of every religion in the East. The Christians were as bad as the rest in the extreme license of their lives. There were few priests, but they were a disgrace to their name. The Arabs and the Persians had introduced and made common the most detestable forms of vice. Ormuz was said to be a Babel for its confusion of tongues, and for its moral abominations to match the cities of the Plain. A lawful marriage was a rare exception. Foreigners, soldiers and merchants, threw off all restraint in the indulgence of their passions ... Avarice was made a science: it was studied and practiced, not for gain, but for its own sake, and for the pleasure of cheating. Evil had become good, and it was thought good trade to break promises and think nothing of engagements ...[25]

Depiction in literature

Ormus is mentioned in a passage from

See also

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Hormuz Island

- Hormizd I

- Portuguese Oman

References

- ^ Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p.122

- ^ Shabankareyi, Muhammad. Majma al-Ansab. p. 215.

- ^ Ebrahimi, Qorbanali (1384). "Hormoz-Hormuz". Motale'at Irani. 4 (7): 48.

- ^ a b c Rezakhani, Khodadad (27 February 2020). "The Kingdom of Hormuz". Iranologie.com. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Shabankareyi, Muhammad b. Ali (1363). Majma al-Ansab. Tehran: Amir Kabir. p. 215.

- ^ Vosoughi, M. B. The Kings of Hormoz. p. 92.

- ^ #127 The Travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd; E.P. Dutton & Co, London and Toronto; New York, 1926 ~ p. 63. Although Marco Polo refers to the island on which was the city of Hormoz, Collis states that at that time Hormoz was on the mainland. #85 Collis, Maurice. Marco Polo. London, Faber and Faber Limited, 1959~ p. 24.

- ^ "Nothing found for Hormuz Essays 3 3". Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ Risso, Patricia, Oman And Muscat: an Early Modern History, Croom Helm, London, 1986 ~ p. 10.

- ^ #252 Stiffe, A. W., "The Island of Hormoz (Ormuz)", Geographical Magazine, London, 1874 (Apr.), vol. 1 pp. 12–17 ~ p. 14

- ^ a b Floor, Willem. "Hormuz ii. Islamic Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0321084439.

- ^ JSTOR 43731513.

- ^ Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, 1997, 288

- ^ James Silk Buckingham Travels in Assyria, Media, and Persia, Oxford University Press, 1829, p459

- ^ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 pp39

- ^ Charles Belgrave, Personal Column, Hutchinson, 1960 p98

- ^ Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p6

- ^ Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984 p69

- ^ Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki dar Arshiv-e Melli-e Porteghal". Asnad.

- ^ Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki..." Asnad.

- ^ a b Peter Padfield, Tide of Empires: Decisive Naval Campaigns in the Rise of the West, Routledge 1979 p65

- ^ pesh, a Semitic root for 'mouth', often connotes speech.

- ^ The Book of Duarte Barbosa: An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and their inhabitants, written by Duarte Barbosa and completed about the year 1518 AD, 1812 translation by the Royal Academy of Sciences Lisbon, Asian Educational Services 2005

- Francis Xavier, Henry James Coleridge, The Life and Letters of St. Francis Xavier 1506–1556, Asian Educational Services 1997 Edition p 104–105

- ISBN 9781139471183. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

Bibliography

- Aubin, Jean. “Les Princes d’Ormuz du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Journal asiatique, vol. CCXLI, 1953, pp. 77–137.

- Natanzi, Mo'in ad-Din. Montakhab ut-Tawarikh-e Mo'ini. ed. Parvin Estakhri. Tehran: Asateer, 1383 (2004).

- Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki dar Arshiv-e Melli-ye Porteghal Darbarey-e Hormuz o Khaleej-e Fars." Barrasihaa-ye Tarikhi (1356–1357).

- Shabankareyi, Muhammad b Ali. Majma al-Ansab. ed. Mir-Hashem Mohadess. Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1363 (1984).

- Vosoughi, Mohammad Bagher. "the Kings of Hormuz: from the Beginning until the Arrival of the Portuguese." in Lawrence G. Potter (ed.) The Persian Gulf in History, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009.[1]