Ornithology

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

|

Ornithology, from

While early ornithology was principally concerned with descriptions and distributions of species, ornithologists today seek answers to very specific questions, often using birds as models to test hypotheses or predictions based on theories. Most modern biological theories apply across life forms, and the number of scientists who identify themselves as "ornithologists" has therefore declined.[4] A wide range of tools and techniques are used in ornithology, both inside the laboratory and out in the field, and innovations are constantly made. Most biologists who recognise themselves as "ornithologists" study specific biology research areas, such as anatomy, physiology, taxonomy (phylogenetics), ecology, or behaviour.[5]

Definition and etymology

The word "ornithology" comes from the late 16th-century Latin ornithologia meaning "bird science" from the Greek ὄρνις ornis ("bird") and λόγος logos ("theory, science, thought").[6]

History

The history of ornithology largely reflects the trends in the history of biology, as well as many other scientific disciplines, including ecology, anatomy, physiology, paleontology, and more recently, molecular biology. Trends include the move from mere descriptions to the identification of patterns, thus towards elucidating the processes that produce these patterns.

Early knowledge and study

Humans have had an observational relationship with birds since

Cultures around the world have rich vocabularies related to birds.

The earliest record of falconry comes from the reign of Sargon II (722–705 BC) in

Several early German and French scholars compiled old works and conducted new research on birds. These included

In the 17th century,

Towards the late 18th century,

Scientific studies

The emergence of ornithology as a scientific discipline began in the 18th century, when

No doubt the preoccupation with widely extended geographical ornithology, was fostered by the immensity of the areas over which British rule or influence stretched during the 19th century and for some time afterwards.

— Moreau[43]

The bird collectors of the Victorian era observed the variations in bird forms and habits across geographic regions, noting local specialization and variation in widespread species. The collections of museums and private collectors grew with contributions from various parts of the world. The naming of species with binomials and the organization of birds into groups based on their similarities became the main work of museum specialists. The variations in widespread birds across geographical regions caused the introduction of trinomial names.

The search for patterns in the variations of birds was attempted by many.

The

For Darwin, the problem was how species arose from a common ancestor, but he did not attempt to find rules for delineation of species. The

Early ornithologists were preoccupied with matters of species identification. Only systematics counted as true science and field studies were considered inferior through much of the 19th century.[51] In 1901, Robert Ridgway wrote in the introduction to The Birds of North and Middle America that:

There are two essentially different kinds of ornithology: systematic or scientific, and popular. The former deals with the structure and classification of birds, their synonymies, and technical descriptions. The latter treats of their habits, songs, nesting, and other facts pertaining to their life histories.

This early idea that the study of living birds was merely recreation held sway until ecological theories became the predominant focus of ornithological studies.

Sometimes it seems that elaborate plans and statistics are made to prove what is commonplace knowledge to the mere collector, such as that hunting parties often travel more or less in circles.

— Ticehurst[42]

David Lack's studies on population ecology sought to find the processes involved in the regulation of population based on the evolution of optimal clutch sizes. He concluded that population was regulated primarily by

Birds were also widely used in studies of the niche hypothesis and

The study of imprinting behaviour in ducks and geese by

The growth of genetics and the rise of molecular biology led to the application of the gene-centered view of evolution to explain avian phenomena. Studies on kinship and altruism, such as helpers, became of particular interest. The idea of inclusive fitness was used to interpret observations on behaviour and life history, and birds were widely used models for testing hypotheses based on theories postulated by W. D. Hamilton and others.[49]

The new tools of molecular biology changed the study of bird systematics, which changed from being based on

Rise to popularity

The use of

The rise of field guides for the identification of birds was another major innovation. The early guides such as

from the pioneering illustrated handbooks ofThe interest in

Organizations were started in many countries, and these grew rapidly in membership, most notable among them being the

Techniques

The tools and techniques of ornithology are varied, and new inventions and approaches are quickly incorporated. The techniques may be broadly dealt under the categories of those that are applicable to specimens and those that are used in the field, but the classification is rough and many analysis techniques are usable both in the laboratory and field or may require a combination of field and laboratory techniques.

Collections

The earliest approaches to modern bird study involved the collection of eggs, a practice known as oology. While collecting became a pastime for many amateurs, the labels associated with these early egg collections made them unreliable for the serious study of bird breeding. To preserve eggs, a tiny hole was made and the contents extracted. This technique became standard with the invention of the blow drill around 1830.[40] Egg collection is no longer popular; however, historic museum collections have been of value in determining the effects of pesticides such as DDT on physiology.[71][72] Museum bird collections continue to act as a resource for taxonomic studies.[73]

The use of bird skins to document species has been a standard part of systematic ornithology. Bird skins are prepared by retaining the key bones of the wings, legs, and skull along with the skin and feathers. In the past, they were treated with

Other methods of preservation include the storage of specimens in spirit. Such wet specimens have special value in physiological and anatomical study, apart from providing better quality of DNA for molecular studies.[74] Freeze drying of specimens is another technique that has the advantage of preserving stomach contents and anatomy, although it tends to shrink, making it less reliable for morphometrics.[75][76]

In the field

The study of birds in the field was helped enormously by improvements in optics. Photography made it possible to document birds in the field with great accuracy. High-power spotting scopes today allow observers to detect minute morphological differences that were earlier possible only by examination of the specimen "in the hand".[77]

The capture and marking of birds enable detailed studies of life history. Techniques for capturing birds are varied and include the use of

The bird in the hand may be examined and

Techniques for estimating population density include point counts, transects, and territory mapping. Observations are made in the field using carefully designed protocols and the data may be analysed to estimate bird diversity, relative abundance, or absolute population densities.[83] These methods may be used repeatedly over large timespans to monitor changes in the environment.[84] Camera traps have been found to be a useful tool for the detection and documentation of elusive species, nest predators and in the quantitative analysis of frugivory, seed dispersal and behaviour.[85][86]

In the laboratory

Many aspects of bird biology are difficult to study in the field. These include the study of behavioural and physiological changes that require a long duration of access to the bird. Nondestructive samples of blood or feathers taken during field studies may be studied in the laboratory. For instance, the variation in the ratios of stable hydrogen isotopes across latitudes makes establishing the origins of migrant birds possible using mass spectrometric analysis of feather samples.[87] These techniques can be used in combination with other techniques such as ringing.[88]

The first attenuated vaccine developed by Louis Pasteur, for fowl cholera, was tested on poultry in 1878.[89] Anti-malarials were tested on birds which harbour avian-malarias.[90] Poultry continues to be used as a model for many studies in non-mammalian immunology.[91]

Studies in bird behaviour include the use of tamed and trained birds in captivity. Studies on bird intelligence and song learning have been largely laboratory-based. Field researchers may make use of a wide range of techniques such as the use of dummy owls to elicit mobbing behaviour, and dummy males or the use of call playback to elicit territorial behaviour and thereby to establish the boundaries of bird territories.[92]

Studies of bird migration including aspects of navigation, orientation, and physiology are often studied using captive birds in special cages that record their activities. The Emlen funnel, for instance, makes use of a cage with an inkpad at the centre and a conical floor where the ink marks can be counted to identify the direction in which the bird attempts to fly. The funnel can have a transparent top and visible cues such as the direction of sunlight may be controlled using mirrors or the positions of the stars simulated in a planetarium.[93]

The entire genome of the domestic fowl (

The chicken has long been a model organism for studying vertebrate developmental biology. As the embryo is readily accessible, its development can be easily followed (unlike mice). This also allows the use of electroporation for studying the effect of adding or silencing a gene. Other tools for perturbing their genetic makeup are chicken embryonic stem cells and viral vectors.[99]

Collaborative studies

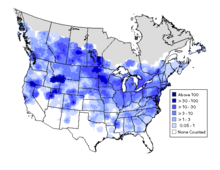

With the widespread interest in birds, use of a large number of people to work on collaborative ornithological projects that cover large geographic scales has been possible.

Applications

Wild birds impact many human activities, while domesticated birds are important sources of eggs, meat, feathers, and other products. Applied and economic ornithology aim to reduce the ill effects of problem birds and enhance gains from beneficial species.

The role of some species of birds as pests has been well known, particularly in agriculture. Granivorous birds such as the queleas in Africa are among the most numerous birds in the world, and foraging flocks can cause devastation.[107][108] Many insectivorous birds are also noted as beneficial in agriculture. Many early studies on the benefits or damages caused by birds in fields were made by analysis of stomach contents and observation of feeding behaviour.[109] Modern studies aimed at managing birds in agriculture make use of a wide range of principles from ecology.[110] Intensive aquaculture has brought humans into conflict with fish-eating birds such as cormorants.[111]

Large flocks of pigeons and starlings in cities are often considered as a nuisance, and techniques to reduce their populations or their impacts are constantly innovated.

Many species of birds have been driven to

See also

References

- ^ Newton, Alfred; Lydekker, Richard; Roy, Charles S.; Shufeldt, Robert W. (1896). A dictionary of birds. London: A. and C. Black.

- ISBN 978-0-12-517366-7.

- ^ JSTOR 1309464.

- ^ S2CID 87377120.

- ISBN 978-0-19-852086-3.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ S2CID 4033666.

- ^ Anker, Jean (1979). Bird books and bird art. Springer-Science. pp. 1–5.

- PMID 15090648. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Newton, Alfred (1884). Ornithology. Reprinted from Encyclopædia Britannica (9th Ed.). [S.l. : s.n.

- ^ Newton, Alfred (1893–1896). A Dictionary of Birds. Adam & Charles Black, London.

- ^ "Hawaiian bird names". birdinghawaii.co.uk/. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ Gill, Frank & Wright, M. (2006). Birds of the world: Recommended English Names. Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- PMID 17547781.

- ^ Shapiro, M. "Native bird names". Richmond Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 2007-08-16. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Funk, E. M. & Irwin, M. R. (1955). Hatching Operation and Management. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Keller, Otto (1913). Die Antike Tierwelt (in German). Vol. 2. Leipzing: Wilhelm Engelmann. pp. 1–43.

- JSTOR 23001825.

- ^ Lack, David (1965) Enjoying Ornithology. Taylor & Francis. pp. 175–176.

- ^ Aristotle. Historia Animalium. Translated by D'Arcy Thompson.

- ^ Lincoln, Frederick C.; Peterson, Steven R.; Zimmerman, John L. (1998). Migration of birds (Report). U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. Circular 16. Jamestown, ND: Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. Archived from the original on 2007-05-18.

- ^ Allen, JA (1909). "Biographical memoir of Elliott Coues" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs. 6: 395–446. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Payne, S. (1929). "The Myth of the Barnacle Goose". Int. J. Psycho-Anal. 10: 218–227.

- S2CID 144264511.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ van Oppenraay, Aafke M.I. (2017). "Avicenna's Liber de animalibus (Abbreviatio Avicennae) - Preliminaries and State of Affairs" (PDF). Documenti e Studi Sulla Tradizione Filosofica Medievale. 28: 401–416. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b Miall, L. C. (1911). History of Biology. Watts and Co.

- JSTOR 1005629.

- JSTOR 2411751.

- ^ Lind, L. R. (1963). Aldrovandi on Chickens: The Ornithology of Ulisse Aldrovandi, vol. 2, Bk xiv, translated and edited by L. R. Lind. University of Oklahoma Press.

- ^ Aldrovandi, Ulisse (1599). Ornithologiae.

- .

- OCLC 3423785.

- ^ White, Jeanne A. (1999). "Ornithology Collections in the Libraries at Cornell University: A Descriptive Guide". Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- S2CID 144805851.

- ^ Browne, Thomas (with notes by Thomas Southwell) (1902). Notes and Letters on the Natural History of Norfolk, more especially on the birds and fishes. London: Jarrold & Sons. pp. i–xxv.

- ^ Mullens, W.H. (1909). "Some early British Ornithologists and their works. VII. John Ray (1627-1705) and Francis Willughby (1635-1672)" (PDF). British Birds. 2 (9): 290–300. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ White, Jeanne A. (1999-06-10). "Hill Collection — 18th c. French authors & artists". Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ ISBN 978-0691036328.

- ^ Farber, Paul L. (1982). The Emergence of Ornithology as a Scientific Discipline, 1760–1850. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Boston.

- ^ S2CID 83849594.

- .

- ^ O’Hara, Robert J. (1988). "Diagrammatic classifications of birds, 1819–1901: views of the natural system in 19th-century British ornithology". Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici: 2746–2759.

- ISBN 978-0-674-64485-4.

- ^ Fürbringer, Max (1888). Untersuchungen zur morphologie und systematik der vogel. Volume II (in German). Amsterdam: Verlag von TJ. Van Holkema.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- .

- ^ PMID 2683069.

- ^ Junker, Thomas (2003). "Ornithology and the genesis of the Synthetic Theory of Evolution" (PDF). Avian Science. 3 (2&3): 65–73. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-0691049540.

- ^ Alexander, H. G. (1915). "A Practical Study of Bird Ecology". British Birds. 8 (9).

- ^ Lack, David (1959). "Watching migration by Radar" (PDF). British Birds. 52 (8): 258–267. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Crook, J. H. (1964). "The evolution of social organization and visual communication in the weaver birds (Ploceinae)". Behaviour. Supplement. 10: 1–178.

- ISBN 978-0-19-857174-2.

- ^ Brown, J. L. (1964). "The evolution of diversity in avian territorial systems" (PDF). Wilson Bull. 76: 160–169. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ "Contents". The Auk. 98 (2). Searchable Ornithological Research Archive. 1981.

- ^ O'Hara, Robert J. (1991). "Essay review of Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: A Study in Molecular Evolution by Charles G. Sibley and Jon E. Ahlquist". Auk. 108 (4): 990–994.

- S2CID 6683688. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-30. Retrieved 2007-11-30.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21708732.

- .

- S2CID 143634420.

- ^ Dunlap, Tom. "Tom Dunlap on Early Bird Guides. Environmental History January 2005". Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Briand, Frederic (November 2012). "From Bird Scientist to Spy: the Name is Bond, James Bond". National Geographic.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- )

- ^ "North American Breeding Bird Survey".

- ISBN 978-0856610233.

- ^ Green, Rhys E. & Scharlemann, Jörn P. W. (2003). "Egg and skin collections as a resource for long-term ecological studies" (PDF). Bull. B.O.C. 123A: 165–176. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- .

- ^ Livezey, Bradley C. (2003). "Avian spirit collections: attitudes, importance and prospects" (PDF). Bull. B.O.C. 123A: 35–51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ Winker, K. (1993). "Specimen shrinkage in Tennessee warblers and Traill's flycatchers" (PDF). J. Field Ornithol. 64 (3): 331–336. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30.

- ^ Bjordal, H. (1983). "Effects of deep freezing, freeze-drying and skinning on body dimensions of House Sparrows (Passer domesticus)". Cinclus. 6: 105–108.

- ISBN 978-0395602379.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ "Techniques to capture Seaducks in the Chesapeake Bay and Restigouche River". USGS. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Ralph, C. John; Geupel, Geoffrey R.; Pyle, Peter; Martin, Thomas E. & DeSante, David F. (1993). Handbook of field methods for monitoring landbirds. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-144-www. Albany, CA (PDF). Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Walther, B. A. & Clayton, D. H. (1997). "Dust-ruffling: A simple method for quantifying ectoparasite loads of live birds" (PDF). J. Field Ornithol. 68 (4): 509–518. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Bibby C., Jones M. & Marsden, S. (1998). Expedition Field Techniques – Bird Surveys. Expedition Advisory Centre, Royal Geographical Society, London. Archived from the original on 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ^ Dunn EH, Bart J, Collins BT, Craig B, Dale B, Downes CM, Francis CM, Woodley S (2006). Monitoring bird populations in small geographic areas (PDF). Canadian Wildlife Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Winarni, N., Carroll, J.P. & O'Brien, T.G (2005). The application of camera traps to the study of Galliformes in southern Sumatra, Indonesia. pp. 109–121 in: Fuller, R.A. & Browne, S.J. (eds) 2005. Galliformes 2004. Proceedings of the 3rd International Galliformes Symposium. World Pheasant Association, Fordingbridge, UK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - .

- S2CID 54943028.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-3540434085.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Pasteur, Louis (1880). "De l'attenuation du virus du chokra des poules" (PDF). Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 91: 673–680. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- PMID 18123477.

- ISBN 978-0-12-370634-8.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 53157104.

- JSTOR 4083048.

- ^ "Zebra finch genome assembly release". The songbird genome sequencing project. 6 Aug 2008. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- PMID 15455034.

- PMID 17472912.

- S2CID 17226774.

- S2CID 17239411.

- PMID 15621526.

- hdl:10535/2968.

- S2CID 21914046. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Wing, L. (1947). Christmas census summary 1900–1939. State College of Washington, Pullman. Mimeograph.

- ^ "Great Backyard Bird Count".

- ^ "Étude des populations d'oiseaux du Québec". oiseauxqc.org.

- ^ "Project PigeonWatch".

- ^ EURING Coordinated bird-ringing in Europe. Euring.org. Retrieved on 2013-02-22.

- ^ Elliott, Clive C.H. (2006). "Bird population explosions in agroecosystems — the quelea, Quelea quelea, case history" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Sinica. 52: 554–560. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Jaegar, Michael & William A. Erickson (1980). "Levels of bird damage to Sorghum in the Awash basin of Ethiopia and the effects of the control of Quelea nesting colonies". Proceedings of the 9th Vertebrate Pest Conference.

- ^ Kalmbach, E. R. (1934). "Field observation in economic ornithology" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 46 (2): 73–90. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- .

- JSTOR 1521537.

- ^ Geis, Aelred D. (1976). "Effect of building design and quality on nuisance bird problems". Proceedings of the 7th Vertebrate Pest Conference.

- JSTOR 3784047.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Factsheet on Avian Influenza". CDC. 2017-04-13.

- PMID 15931279.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Allan, J., Orosz, A. (2001). "The Costs of Birdstrikes to Commercial Aviation". Proceedings of Birdstrike 2001, Joint Meeting of Birdstrike Committee USA/Canada. Calgary, Alberta.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gregory, R. D.; Noble, D.; Field, R.; Marchant, J.; Raven, M.; Gibbons, D. W. (2003). "Using birds as indicators of biodiversity" (PDF). Ornis Hung. 12–13: 11–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-27. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- JSTOR 1370218.

- ISBN 978-0946888399.

- .

Additional sources

- Birkhead T, Wimpenny J; Montgomerie B (2014). Ten Thousand Birds: Ornithology since Darwin. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691151977.

- Chansigaud, Valerie (2009). History of Ornithology. ISBN 978-1-84773-433-4.

- Gurney, John Henry (1921). "Early annals of ornithology". Nature. 108 (2713): 268. S2CID 4033666. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Newton, Alfred (1884). Ornithology. [S.l. : s.n.(Reprinted from the 1884 Encyclopædia Britannica)

- Podulka, Sandy; Eckhardt, Marie; Otis, Daniel (2001). "Birds and Humans: A Historical Perspective". In Podulka, Sandy; Rohrbaugh, Ronald W.; Bonney, Rick (eds.). Handbook of Bird Biology (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-938027-62-1.

- Walters, Michael (2005). A Concise History of Ornithology. ISBN 978-1-84773-433-4.

External links

- Lewis, Daniel. The Feathery Tribe: Robert Ridgway and the Modern Study of Birds. Yale University Press. [1].

- Ornithologie (1773–1792) Francois Nicholas Martinet Digital Edition Smithsonian Digital Libraries

- "West Midland Bird Club: Older Organisations". Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2004.

- History of ornithology in North America

- History of ornithology and ornithology collections in Victoria, Australia on Culture Victoria

- History of ornithology in China[usurped]

- Hill ornithology collections

- Newton, Alfred; Mitchell, Peter Chalmers (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 299–326.