User:Doug Weller/Bedson

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

This article possibly contains original research. |

Natufian | |

| Site notes | |

|---|---|

| Condition | Ruins |

| Public access | Yes |

The Aaiha Hypothesis is a theory suggesting that there is a large

The hypothesis was first suggested by exploration geologist Christian O'Brien in 1983 who called the location Achaia in his first book The Megalithic Odyssey. One peer review from John Barnatt marginalized O'Brien's later work with academia.[1] Edward F. Malkowski has recently discussed O'Brien's theories in 2006 in his book "The Spiritual Technology of Ancient Egypt", noting "O'Brien's book, The Genius of the Few, received little notice. A few scholars, however, including the British Museum Sumerian expert Irving Finkel, praised it. In 1996, British author Andrew Collins expounded on O'Brien's work in From the Ashes of Angels. He goes on to mention that "When these tablets, now stored at the University of Philadelphia museum, were first translated, they were believed to be a Sumerian creation myth, and the personalities depicted in the epic stories were interpreted as gods. According to exploration geologist and historian Christian O'Brien (1915-2001), however, this religious interpretation was a product of preconceived notions; according to his analysis, it has had 'disastrous results for the truth'."[2]

The hypothesis is being updated and expanded to make various reliable geographical, archaeological and mythological suggestions in order to promote further investigation and research of the

The

Introduction

2009 Survey of Aaiha

In November 2009, along with

Eden in Lebanon

The prophet Ezekiel mentions that the trees in the Garden of Eden come from Lebanon (Ezekiel 31:15–18). Based on an analysis of this chapter, Terje Stordalen has suggested "an apparent identification of Eden and Lebanon in Ezekiel 31" and symbolical relationships between Eden and Lebanon.[4] John Pairman Brown wrote "it appears that the Lebanon is an alternative placement in Phoenician myth (as in Ez 28,13, III.48) of the Garden of Eden".[5] and Paul Swarup also discusses connections between paradise, the garden of Eden and the forests of Lebanon (possibly used symbolically) within prophetic writings.[6]

Geography of Aaiha

Underground river to the Hasbani, the chasm of the Abzu

During the 2009 survey, the Lebanese

Aaiha (or Aiha) is a

The village sits ca. 3,750 feet (1,140 m) above sea level and the small population is predominantly

The village is situated on a ridge next to Aaiha plain, Aaiha lake or Aaiha temporary wetland, which forms a near perfect circlular shape, approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) in

| “ | Now Panium is thought to be the fountain of the Jordan, but in reality it is carried thither after an occult manner from the place called Phiala : This place lies as you go up to Trachonitis, and is an hundred and twenty furlongs from Caesarea, and is not far out of the road on the right hand ; and indeed it hath its name of Phiala (vial or bowl) very justly, from the roundness of its circumference, as being round like a wheel; its water continues always up to its edges, without either sinking or running over. And as this origin of the Jordan was formerly not known, it was discovered so to be when Philip was Tetrarch of Trachonitis ; for he had chaff thrown into Phiala, and it was found at Panium where the ancients thought the fountain head of the river was, whither it had been therefore carried (by the waters). [22] | ” |

Edward Robinson commented that this story would appear still current in respect to this chasm and underground stream leading to the Hasbani.[9] Some neolithic flints have been recovered in this area, in the hills 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) north of Rashaya.[23]

Kfar Qouq - The Pottery Place

Kfar Qouq (and variations of spelling) is a village in

The population of the hillside village is predominantly

Limestone White Ware - the first prototype pottery

The Aaiha hypothesis suggests the first prototype of pottery could have developed using pyrotechnology to create

White Ware was commonly found in

Archaeology of Aaiha

The

ASPRO stands for the "Atlas des sites Prochaine-Orient" (Atlas of Near East archaeological sites), a

The periods, cultures, features and date ranges of the ASPRO chronology are shown below:

| ASPRO Period | Names | Dates |

| Period 1 | Zarzian final |

12000-10300 BP or 12000-10200 cal. BCE |

| Period 2 | Protoneolithic, Harifian |

10300-9600 BP or 10200-8800 cal. BCE |

| Period 3 | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), PPNB ancien | 9600-8000 BP or 8800-7600 cal. BCE |

| Period 4 | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), PPNB moyen | 8000-8600 BP or 7600-6900 cal. BCE |

| Period 5 | Dark Faced Burnished Ware ( 0 | 8000-7600 BP or 6900-6400 cal. BCE |

| Period 6 | Halaf, Ubaid 1 |

7600-7000 BP or 6400-5800 cal. BCE |

| Period 7 | Halaf final, Ubaid 2 |

7000-6500 BP or 5800-5400 cal. BCE |

| Period 8 | Pottery Neolithic B (PNB), Ubaid 3 | 6500-6100 BP or 5400-5000 cal. BCE |

| Period 9 | Ubaid 4 | 6100-5700 BP or 5000-4500 cal. BCE |

| The Stone Age |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene) |

|

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

The Aaiha hypothesis suggests that the founders and inhabitants of the settlement at Aaiha were the

Qaraoun culture

The Qaraoun culture is a culture of the

Qaraoun II

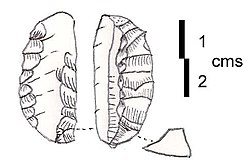

Qaraoun II is the type site of the Neolithic Qaraoun culture in the Beqaa valley. It is located on top of a gorge on the right of the river. A large area of the site is now completely destroyed but a large collection of flints was collected by workers and examined by Jacques Cauvin and Marie-Claire Cauvin. The collection includes a full range of Heavy Neolithic material with oval, almond shaped and rectangular axes, trapezoidal and rectangular chisels, thick discoid, side and end scrapers on large blades, picks and burins and a full range of cores. The Cauvins suggested the material had similarities to the Neolithic moyen assemblage from Byblos and Andrew Moore theorized that Heavy Neolithic stations such as this were used during earlier and later periods.[23] James Mellaart suggested the Heavy Neolithic industry of the culture dated to a period before the Pottery Neolithic at Byblos (10600 to 6900 BCE according to the ASPRO chronology).[46]

Heavy and Trihedral Neolithic

Heavy Neolithic (alternatively, Gigantolithic) is a style of large

The term "Heavy Neolithic" was translated by Lorraine Copeland and Peter J. Wescombe from Henri Fleisch's term "gros Neolithique", suggested by Dorothy Garrod for adoption to describe a particular flint industry that was identified at sites near Qaraoun in the Beqaa Valley.[47] The industry was also termed "Gigantolithic" and confirmed as Neolithic by A. Rust and Dorothy Garrod.

The industry was initially mistaken for

The industry has been found at surface stations in the Beqaa Valley and on the seaward side of the mountains. Heavy Neolithic sites were found near sources of

-

Massive nosed scraper on a flake with irregular jagged edges, notches and "noses".

-

Double ended pick, triangular section with narrowing, jagged edges at both ends.

-

Massive steep-scraper on a split cobble or flake with direct retouch all around and cortex on the crest.

-

Thick and heavy biface, retouched all over with jagged and irregular edges.

Trihedral Neolithic is a name given by archaeologists to a style (or

Orange slice is an early

A Canaanean blade is an

Neolithic hoes at Kaukaba and their relationship to Enlil, creator in the Song of the hoe

Kaukaba, Kaukabet El-Arab or Kaukaba Station is a

The

"Not only did the lord make the world appear in its correct form, the lord who never changes the destinies which he determines – Enlil – who will make the human seed of the Land come forth from the earth – and not only did he hasten to separate heaven from earth, and hasten to separate earth from heaven, but, in order to make it possible for humans to grow in "where flesh came forth" [the name of a cosmic location], he first raised the axis of the world at

Dur-an-ki.[60]

The myth continues with a description of Enlil creating daylight with his hoe; he goes on to praise its construction and creation.

The nearby sites: Jericho, Tell Aswad, Tell Ramad, Iraq ed-Dubb and Labweh

Archaeobotany - Emmer and Barley domestication event location

Emmer

Graham Wilcox et al write "Wild emmer wheat was recognized in 1873 by Fredrich August Körnicke, a German Agro-Botanist, in the herbarium of the National Museum of Vienna.[68] He found it among the specimiens of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) that were collected by the botanist Theodor Koyschy in 1855 in Rashaya on the northwestern slope of Mount Hermon.[69] Körnicke described this plant specimen in 1889 as wild emmer wheat (Triticum vulgare var dicoccoides).[68] He also recognized that this plant is the wild progenitor 'prototype' of cultivated wheat".[70] Concluding "Archaeobotanical studies strongly suggest that wild emmer was possibly twice and independently taken into cultivation: (1) in the southern Levant and (2) in the northern Levant."[71][72][73] Wilcox writes that "According to Feldman and Kislev, the hybridization could have occurred in the vicinity of Mount Hermon and the catchment area of the Jordan River because of the larger morphological, phenological, biochemical and molecular variation of wild emmer from southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq or southwestern Iran."[74][75]

Mordechai Kislev and Moshe Feldman suggested that wild emmer evolved around three to five hundred thousand years ago in the vicinity of

Luo et al suggested that emmer was domesticated in the

Barley

Following the work of

Mythology of Aaiha

Ancestor worship in ancient Sumer

The sun god is only modestly mentioned in Sumerian mythology with one of the notable exceptions being the

Myths recording Aaiha

LC Class | PJ3711 .Y34 1983 | |

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions is a

It was first published by

Contents

Some of the myths contained in the book suggested to record details of the Aaiha settlement are shown below:

| Modern title | Museum number | Barton's title |

|---|---|---|

| Debate between sheep and grain | 14,005 | A Creation Myth |

| Barton Cylinder | 8,383 | The oldest religious text from Babylonia |

| Enlil and Ninlil | 9,205 | Enlil and Ninlil |

| Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) | 11,065 | A hymn to Dungi |

| Old Babylonian oracle | 8,322 | An Old Babylonian oracle |

| Kesh temple hymn | 8,384 | Fragment of the so-called "Liturgy to Nintud" |

| Debate between Winter and Summer | 8,310 | Hymn to Ibbi-Sin |

| Hymn to Enlil | 8,317 | An excerpt from an exorcism |

| Lament for Ur | 19,751, 2,204, 2,270 & 2,302 | A prayer for the city of Ur |

Kesh temple hymn

In the Kesh temple hymn, the first recorded description (c. 2600 BC) of a domain of the gods is a garden The four corners of heaven became green for Enlil like a garden."[60] In an earlier translation of this myth by George Aaron Barton in Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions he considered it to read "In hursag the garden of the gods were green."[82]

Atrahasis

Sumerian paradise is described as a garden in the myth of

When the gods, like man. Bore the labour, carried the load. The gods' load was great, the toil greivous, the trouble excessive. The great Annanuki, the Seven, Were making the Igigu undertake the toil.[87]

The Igigi then rebel against the dictatorship of Enlil, setting fire to their tools and surrounding Enlil's great house by night. On hearing that toil on the irrigation channel is the reason for the disquiet, the Annanuki council decide to create man to carry out agricultural labour.[87]

Debate between sheep and grain

Another Sumerian creation myth, the Debate between sheep and grain opens with a location "the hill of heaven and earth", and describes various agricultural developments in a pastoral setting. This is discussed by Edward Chiera as "not a poetical name for the earth, but the dwelling place of the gods, situated at the point where the heavens rest upon the earth. It is there that mankind had their first habitat, and there the Babylonian Garden of Eden is to be placed."[88] The Sumerian word Edin, means "steppe" or "plain",[89] so modern scholarship has abandoned the use of the phrase "Babylonian Garden of Eden" as it has become clear the "Garden of Eden" was a later concept.

Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh describes Gilgamesh travelling to a wondrous garden of the gods that is the source of a river, next to a mountain covered in cedars, and references a "plant of life". In the myth, paradise is identified as the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim (Ziusudra), was taken by the gods to live forever. Once in the garden of the gods, Gilgamesh finds all sorts of precious stones, similar to Genesis 2:12:

There was a garden of the gods: all round him stood bushes bearing gems ... fruit of carnelian with the vine hanging from it, beautiful to look at; lapis lazuli leaves hung thick with fruit, sweet to see ... rare stones, agate and pearls from out the sea.[90]

Song of the hoe

The

Hymn to Enlil

A Hymn to Enlil praises the leader of the Sumerian pantheon in the following terms:

You founded it in the

Dur-an-ki, in the middle of the four quarters of the earth. Its soil is the life of the Land, and the life of all the foreign countries. Its brickwork is red gold, its foundation is lapis lazuli. You made it glisten on high.[91]

Dilmun as the Aaiha plain

Sumerian paradise has sometimes been associated with

Garden of the gods (Sumerian paradise) - physical features on the ground

Reservoir, Watercourse, Great house site, Granary (temple) site, hut circles, Northeast chasm, Southwest chasm.

In tablet nine of the standard version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh travels to the garden of the gods through the Cedar Forest and the depths of Mashu, a comparable location in Sumerian version is the "Mountain of cedar-felling".[97][98][99] Little description remains of the "jewelled garden" of Gilgamesh because twenty four lines of the myth were damaged and could not be translated at that point in the text.[100]

The name of the mountain is Mashu. As he arrives at the mountain of Mashu, Which every day keeps watch over the rising and setting of the sun, Whose peakes reach as high as the "banks of heaven," and whose breast reaches down to the netherworld, The scorpion-people keep watch at its gate.[98]

Bohl has highlighted that the word Mashu in Sumerian means "twins". Jensen and Zimmern thought it to be the geographical location between

Saria (Sirion / Mount Hermon) and Lebanon tremble at the felling of the cedars.[103][104]

John Day noted that Mount Hermon is the "highest and grandest of the mountains in the area, indeed in the whole of Palestine" at 2,814 metres (9,232 ft) elevation considering it the most likely to contrast with the

In the

Lines 738 to 758 describes the house being finished with "kohl" and a type of plaster from the "edin" canal:

"The fearsomeness of the E-ninnu covers all the lands like a garment. The house! It is founded by An on refined

Annunaki gods place of rendering judgments, from its ...... words of prayer can be heard, its food supply is the abundance of the gods, its standards erected around the house are the Anzu bird (pictured) spreading its wings over the bright mountain. E-ninnu´s clay plaster, harmoniously blended clay taken from the Edin canal, has been chosen by Lord Nin-jirsu with his holy heart, and was painted by Gudea with the splendors of heaven as if kohl were being poured all over it."[111]

Thorkild Jacobsen considered this "Idedin" canal meant an as yet unidentified "Desert Canal", which he considered "probably refers to an abandoned canal bed that had filled with the characteristic purplish dune sand still seen in southern Iraq."[96][96]

Concluding remarks

Billions of people believe in a fictional God or Gods and humankind has become distracted from our human origins by other values. A correct and full understanding of our past is essential for our future. The information and suggestions here are for informational and further research purposes and liable to change. The purpose of this hypothesis is to attract further investigation, interest, commercial sponsorship, support and whatever it takes to save some highly notable and clearly visible features in Aaiha from being demolished for urbanization. Preparation to bring this to the correct Directorate General of Antiquities, Museum of Lebanese Prehistory and UNESCO attention is being made and any support, suggestions or criticism is welcome.

Key contact list

- Assaad Seif

- Graeme Barker

- Maya Haïdar Boustani

- Leila Badre

- Bassam Jamous

- Frédéric Abbès

- Danielle Stordeur

- Henri de Contenson

- Nigel Goring-Morris

- Avi Gopher

- Lorraine Copeland

- Peter Wescombe

- Marie-Claire Cauvin

- Willem van Zeist

- Irina Bokova

- Najib Mikati

- Walid Jumblatt

- Talal Arslan

- Michel Aoun

- Michel Suleiman

- Gaby Layoun

- Ban Ki-moon

- David Cameron

- Barak Obama

- Pope Benedict XVI

- Tenzin Gyatso

- Gyaincain Norbu

References

- ^ Barnatt, John, review of Christian O'Brien's "The Megalithic Odyssey" Archaeoastronomy Volume VII(l-4) 1984 pp.142–143

- ISBN 978-1-59477-186-6. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Feldman, Moshe and Kislev, Mordechai E., Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, Volume 55, Number 3 - 4 / 2007, pp. 207 - 221, Domestication of emmer wheat and evolution of free-threshing tetraploid wheat in "A Century of Wheat Research-From Wild Emmer Discovery to Genome Analysis", Published Online: 03 November 2008

- ISBN 9789042908543. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ISBN 9783110168822. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ISBN 9780567043849. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ Discover Lebanon - Map of Aaiha

- ^ Wild Lebanon - Wetlands, Lakes and Rivers

- ^ a b c d e f g h Edward Robinson; Eli Smith (1856). Biblical researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A journal of travels in the year 1838. J. Murray. pp. 433–. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ British Druze Society - Druze communities in the Middle East

- ISBN 9783540094142. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ISBN 9780761402831. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Qada' (Caza) Rachaya - Promenade Tourist Brochure, published by The Lebanese Ministry of Tourism

- ^ Munir Said Mhanna (Photos by Kamal el Sahili), Rashaya el Wadi Tourist Brochure, p. 10, Lebanon Ministry of Tourism, Beirut, 2006

- ^ George Taylor (1971). The Roman temples of Lebanon: a pictorial guide. Les temples romains au Liban; guide illustré. Dar el-Machreq Publishers. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut; Lebanon) (2007). Mélanges de l'Université Saint-Joseph. Impr. catholique. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Sir Charles Warren; Claude Reignier Conder (1889). The survey of western Palestine: Jerusalem. The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ISBN 9789004167353. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ a b Palestine Exploration Fund (1869). Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. Published at the Fund's Office. pp. 197–. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ISBN 9789953457741. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ISBN 9781850434405. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ a b Flavius Josephus; William Whiston (1810). The genuine works of Flavius Josephus: containing five books of the Antiquities of the Jews : to which are prefixed three dissertations. Printed for Evert Duyckinck, John Tiebout, and M. & W. Ward. pp. 306–. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 436–442. Cite error: The named reference "Moore" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Geographic.org - Entry about Kfar Qoûq from data supplied by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Bethesda, MD, USA a member of the Intelligence community of the United States of America

- ^ British Druze Society - Druze communities in the Middle East

- ^ Ktèma, Volumes 9-10, Université des sciences humaines de Strasbourg. Centre de recherche sur le Proche-Orient et la Grèce antiques, Université des sciences humaines de Strasbourg, Centre de recherches sur le Proche-Orient et la Grèce antiques, Groupe de recherche d'histoire romaine., 1984.

- ^ Discover Lebanon - Map of Kfar Qouq

- ^ Taylor, George., The Roman temples of Lebanon: a pictorial guide. Les temples romains au Liban; guide illustré, Dar el-Machreq Publishers, p. 145, 176 pages, 1971.

- ^ Qada' (Caza) Rachaya - Promenade Tourist Brochure, published by The Lebanese Ministry of Tourism

- ^ Anīs Furaiḥa (1972). dictionary of the name of towns and villages in Lebanon. Maktabat Lubnān. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Ziadeh, Caroline., Identical letters dated 24 July 2006 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council, July 2006.

- ISBN 9788773040065. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9781560985167. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9782877721769. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ISBN 9781841713526. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ISBN 9780521796668. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ISBN 9789652210234. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Prehistoric Society (London; England); University of Cambridge. University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (1975). Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society for ... University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ISBN 9780710213723. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ISBN 9780860549222. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ a b the earliest settlements in western asia. CUP Archive. 1967. pp. 22–. GGKEY:CKYF53UUXH7. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9782903264536. Retrieved 8 April 2011. Cite error: The named reference "Hours1994" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Association for Field Archaeology (1991). Journal of field archaeology. Boston University. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965). Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, p. 43. Imprimerie Catholique. Retrieved 21 July 2011. Cite error: The named reference "CopelandWescombe1965" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fleisch, Henri., Nouvelles stations préhistoriques au Liban, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, vol. 51, pp. 564-565, 1954.

- ^ Mellaart, James, Earliest Civilizations in the Near East, Thames and Hudson, London, 1965.

- ^ Fleisch, Henri, Nouvelles stations préhistoriques au Liban, BSPF, vol. 51, pp. 564-565, 1954.

- ^ Fleisch, Henri, Les industries lithiques récentes de la Békaa, République Libanaise, Acts of the 6th C.I.S.E.A., vol. XI, no. 1, Paris, 1960.

- ^ Cauvin, Jacques., Le néolithique de Mouchtara (Liban-Sud), L'Anthropologie, vol. 67, 5-6, p. 509, 1963.

- ^ Mellaart, James, Earliest Civilizations in the Near East, Thames and Hudson, London, 1965.

- ^ Francis Adrian Joseph Turville-Petre; Dorothea M. A. Bate; Sir Arthur Keith (1927). Researches in prehistoric Galilee, 1925-1926, p. 108. The Council of the School. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fleisch, Henri., Les industries lithiques récentes de la Békaa, République Libanaise, Acts of the 6th C.I.S.E.A., vol. XI, no. 1. Paris, 1960.

- ^ Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. p. 443.

- ^ L. Hajar, M. Haı¨dar-Boustani, C. Khater, R. Cheddadi., Environmental changes in Lebanon during the Holocene: Man vs. climate impacts, Journal of Arid Environments xxx, 1–10, 2009.

- ^ Hours, Francis., Atlas des sites du proche orient (14000-5700 BP), pp 57, 198 & 490, Maison de l'Orient Mediterraneen, 1994.

- ^ Copeland, Lorraine & Wescombe, P. J., Inventory of Stone Age Sites in Lebanon (1966) Part 2: North - South - East Central Lebanon, pp 23, 37 & 39 Melanges de L'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 42,Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1966.

- ^ J. Cauvin., Mèches en silex et travail du basalte au IVe millénaire en Béka (Liban)., pp. 118-131, Melanges de l'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 45, Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1969.

- ^ Copeland, Lorraine., Neolithic village sites in the South Bekaa, Lebanon., pp. 83-114, Melanges de l'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 45, Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1969.

- ^ Copeland, Lorraine & Wescombe, P. J., Inventory of Stone Age Sites in Lebanon (1966) Part 2: North - South - East Central Lebanon, pp 23, 1-174, Melanges de L'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 42,Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1966.

- ^ a b c ETCSL Translation Cite error: The named reference "ETCSL" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- PMID 12270906.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ^ van Zeist, W. Bakker-Heeres, J.A.H., Archaeobotanical Studies in the Levant 1. Neolithic Sites in the Damascus Basin: Aswad, Ghoraifé, Ramad., Palaeohistoria, 24, 165-256, 1982.

- ISBN 9780521796668. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ISBN 9781857285383. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ Daneille Stordeur, Directeur de recherche (DR1) émérite , CNRS Directrice de la mission permanente El Kowm-Mureybet (Syrie) du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères - Recherches sur le Levant central/sud : Premiers résultats

- ^ Pinhasi R, Fort J, Ammerman AJ., Tracing the Origin and Spread of Agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol 3(12): e410. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030410 (2005)

- ^ Hole, Frank., A Reassessment of the Neolithic Revolution, Paléorient, Volume 10, Issue 10-2, pp. 49-60, 1984.

- ^ a b Körnicke, Frederich August., Wilde Stammformen unserer Kulturweizen. Niederrheiner Gesellsch. f. Natur- und Heilkunde in Bonn, Sitzungsber 46, 1889.

- ^ Aaronsohn, A., Über die in Palästina und Syrienwildwachsend aufgefundenen Getreidearten. Verhandl der k.u.k. zool-bot Ges Wien 59:485–509, 1909.

- ^ Aaronsohn, A., Agricultural and botanical explorations in Palestine. US Department of Agriculture, Washington, Bull Bur PI Industry 180, pp 1–64, 1910.

- ^ Wilcox, George., Ozkan, Hakan., Graner, Andreas., Salamini, Francesco., Kilian, Ben., Geographic distribution and domestication of wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides), Springer Science and Business Media B.V., 27 May 2010

- ^ The Neolithic Southwest Asian Founder Crops, Ehud Weiss and Daniel Zohary, Current Anthropology, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research

- ^ Zohary, Daniel., Monophyletic vs. polyphyletic origin of the crops on which agriculture was founded in the Near East, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, Volume 46, Number 2, Pages 133-142, 1999

- ^ Nevo E, Beiles A, Gutterman Y, Storch N, Kaplan D., Genetic resources of wild cereals in Israel and vicinity. I. Phenotypic variation within and between populations of wild wheat, Triticum dicoccoides. Euphytica 33:717–735, 1983

- ^ Ozbek O, Millet E, Anikster Y, Arslan O, Feldman M., Spatio-temporal genetic variation in populations of wild emmer wheat, Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides, as revealed by AFLP analysis. Theor Appl Genet 115:19–26, 2007.

- ^ Feldman, Moshe and Kislev, Mordechai E., Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, Volume 55, Number 3 - 4 / 2007, pp. 207 - 221, Domestication of emmer wheat and evolution of free-threshing tetraploid wheat in "A Century of Wheat Research-From Wild Emmer Discovery to Genome Analysis", Published Online: 03 November 2008

- ^ Luo MC, Yang ZL, You FM, Kawahara T, Waines JG, Dvorak J., The structure of wild and domesticated emmer wheat populations, gene flow between them, and the site of emmer domestication., Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Theor Appl Genet. 2007 Apr;114(6):947-59. Epub 2007 Feb 22.

- ^ Morrell, Peter L., Clegg, Michael T., Genetic evidence for a second domestication of barley (Hordeum vulgare) east of the Fertile Crescent, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, 21 December 2006

- ^ Badr, A., Muller, K., Schafer-Pregl, R., El Rabey, H., Effgen, S., Ibrahim, H.H., Pozzi, C., Rohde, W., Salamini, F., Mol Biol Evol 17:499-510, 2000.

- ^ Zohary, D., Genet Resources Crop Evol. 17:133-142, 1999.

- ISBN 9780865165465. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ a b George Aaron Barton (1918). Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions. Yale University Press. Retrieved 23 May 2011. Cite error: The named reference "Barton1918" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ISBN 9789004038585. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ISBN 9781605060491. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ISBN 9788483013878. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ISBN 9780802845399. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ a b Millard, A.R., New Babylonian 'Genesis' Story, p. 8, The Tynedale Biblical Archaeology Lecture, 1966; Tyndale Bulletin 18, 3-18, 1967.

- ^ Edward Chiera; Constantinople. Musée impérial ottoman (1924). Sumerian religious texts, pp. 26-. University. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ISBN 9781402025518. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ISBN 9780820478494. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ISBN 9780802844262. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9780813711966. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Friedrich Delitzsch (1881). Wo lag das Paradies?: eine biblisch-assyriologische Studie : mit zahlreichen assyriologischen Beiträgen zur biblischen Länder- und Völkerkunde und einer Karte Babyloniens. J.C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- JSTOR 1359986.

- ISBN 9780812212761. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9780300072785. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Gilgameš and Ḫuwawa (Version A) - Translation, Lines 9A & 12, kur-jicerin-kud

- ^ ISBN 9783856305239. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ISBN 9780865163393. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ISBN 9780292706071. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Lipinski, Edward., ‘El’s Abode. Mythological Traditions Related to Mount Hermon and to the Mountains of Armenia’, Orientalia Lovaniensia periodica 2, 1971.

- ISBN 9789004153486. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9789004127159. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ Oxford Old Testament Seminar p. 9 & 10; John Day (2005). Temple and worship in biblical Israel. T & T Clark. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ ISBN 9780521256001. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ISBN 9780785250104. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Stolz, F., Die Baume des Grottesgartens auf den Libanon, ZAW 84, pp. 141-156, 1972.

- ISBN 9783788700294. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Watson, W.G.E., "Helel" in Dictionaries of Deities and Demons in the Bible, pp. 747-748, eds Karel van der Toorn et al.; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1995.

- ISBN 9780226452388. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ The building of Ningirsu's temple., Cylinder A, Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.