Axis naval activity in Australian waters

There was considerable Axis naval activity in Australian waters during the

The Axis threat to Australia developed gradually and until 1942 was limited to sporadic attacks by German armed merchantmen. The level of Axis naval activity peaked in the first half of 1942 when Japanese submarines conducted anti-shipping patrols off Australia's coast, and Japanese naval aviation attacked several towns in northern Australia. The Japanese submarine offensive against Australia was renewed in the first half of 1943 but was broken off as the Allies pushed the Japanese onto the defensive. Few Axis naval vessels operated in Australian waters in 1944 and 1945, and those that did had only a limited impact.

Due to the episodic nature of the Axis attacks and the relatively small number of ships and submarines committed, Germany and Japan were not successful in disrupting Australian shipping. While the Allies were forced to deploy substantial assets to defend shipping in Australian waters, this did not have a significant impact on the

Australia Station and Australian defences

The maritime approaches to Australia were designated the

The defence of the Australia Station was the

The

The Allied naval forces assigned to the Australia Station were considerably increased following Japan's entry into the war in December 1941 and the beginning of the

In addition to the air and naval forces assigned to protect shipping in Australian waters, fixed defences were constructed to protect the major Australian ports. The Australian Army was responsible for developing and manning coastal defences to protect ports from attacks by enemy surface raiders. These defences commonly consisted of a number of fixed guns defended by anti-aircraft guns and infantry.[12] The Army's coastal defences were considerably expanded as the threat to Australia increased between 1940 and 1942, and reached their peak in 1944.[13] The RAN was responsible for developing and manning harbour defences in Australia's main ports.[14] These defences consisted of fixed anti-submarine booms and mines supported by small patrol craft, and were also greatly expanded as the threat to Australia increased.[15] The RAN also laid defensive minefields in Australian waters from August 1941.[16]

The cargo ships that operated in Australian waters during World War II were mostly crewed by civilians, with the Australian vessels and their crews being organised loosely as the Australian

While the naval and air forces available for the protection of shipping in Australian waters were never adequate to defeat a heavy or coordinated attack, they proved sufficient to mount defensive patrols against the sporadic and generally cautious attacks mounted by the Axis navies during the war.[19]

1939–1941

German surface raiders in 1940

German

On 7 December 1940, the German raiders Orion and Komet arrived off the Australian protectorate of Nauru. During the next 48 hours, they sank four merchant ships.[23] Heavily loaded with survivors from their victims, the raiders departed for Emirau Island where they unloaded the prisoners. After an unsuccessful attempt to lay mines off Rabaul on 24 December, Komet made a second attack on Nauru on 27 December and shelled the island's phosphate plant and dock facilities.[24] This was the last Axis naval attack in Australian waters until November 1941.[25]

The raid on Nauru led to serious concerns in Australia about the supply of phosphates from there and nearby

German surface raiders in 1941

Following the raids on Nauru, Komet and Orion sailed for the Indian Ocean, passing through the Southern Ocean well to the south of Australia in February and March 1941 respectively. Komet re-entered the Australia Station in April en route to New Zealand, and Atlantis sailed east through the southern extreme of the Australia Station in August.[29] Until November, the only casualties from Axis ships on the Australia Station in 1941 were caused by mines laid by Pinguin in 1940. The small trawler Millimumul was sunk with the loss of seven lives after striking a mine off the New South Wales coast on 26 March 1941, and two ratings from a mine disposal party were killed while attempting to defuse a mine which had washed ashore in South Australia on 14 July.[25]

On 19 November 1941, the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney—which had been highly successful in the Battle of the Mediterranean—encountered the disguised German raider Kormoran, approximately 150 mi (130 nmi; 240 km) south west of Carnarvon, Western Australia. Sydney intercepted Kormoran and demanded that she prove her assumed identity as the Dutch freighter Straat Malakka. During the interception, Sydney's captain brought his ship dangerously close to Kormoran. As a result, when Kormoran was unable to prove her identity and avoid a battle she had little hope of surviving, the raider was able to use all her weaponry against Sydney. In the resulting battle, Kormoran and Sydney were both crippled, with Sydney sinking with the loss of all her 645 crew and 78 of Kormoran's crew being either killed in the battle or dying before they could be rescued by passing ships.[30]

Kormoran was the only Axis ship to conduct attacks in Australian waters during 1941 and the last Axis surface raider to enter Australian waters until 1943. There is no evidence to support claims that a

1942

The naval threat to Australia increased dramatically following the outbreak of war in the Pacific. During the first half of 1942, the Japanese mounted a sustained campaign in Australian waters, with Japanese submarines attacking shipping and aircraft carriers conducting a devastating attack on the strategic port of Darwin. In response to these attacks the Allies increased the resources allocated to protecting shipping in Australian waters.[33]

Initial Japanese submarine patrols (January–March 1942)

The first Japanese submarines to enter Australian waters were I-121, I-122, I-123 and I-124, from the Imperial Japanese Navy's (IJN's) Submarine Squadron 6. Acting in support of the Japanese conquest of the Netherlands East Indies, these boats laid minefields in the approaches to Darwin and in the Torres Strait between 12 and 18 January 1942. The mines did not sink or damage any Allied ships.[34]

After completing their mine laying missions the four submarines took station off Darwin to provide the Japanese fleet with warning of Allied naval movements. On 20 January the Australian Bathurst-class corvettes HMAS Deloraine, Katoomba and Lithgow sank I-124 near Darwin. This is the only full-sized submarine that was confirmed to have been sunk by the RAN in Australian waters during World War II.[35] Being the first accessible ocean-going IJN submarine lost after the attack on Pearl Harbor, USN divers attempted to enter I-124 in order to obtain its code books, but were unsuccessful.[36]

Following the conquest of the western Pacific the Japanese made a number of reconnaissance patrols into Australian waters. The submarines (I-1, I-2 and I-3) operated off Western Australia in March 1942, sinking the merchant ships Parigi and Siantar on 1 and 3 March respectively. In addition, I-25 conducted a reconnaissance patrol down the Australian east coast in February and March. During this patrol Nobuo Fujita from the I-25 flew a Yokosuka E14Y1 floatplane over Sydney (17 February), Melbourne (26 February) and Hobart (1 March).[37] Following these reconnaissance operations, I-25 sailed for New Zealand and conducted overflights of Wellington and Auckland on 8 and 13 March respectively.[38]

Japanese naval aviation attacks (February 1942 – November 1943)

The bombing of Darwin was the first of many Japanese naval aviation attacks against targets in Australia. The carriers Shōhō, Shōkaku and Zuikaku—which escorted the invasion force dispatched against Port Moresby in May 1942—had the secondary role of attacking Allied bases in northern Queensland once Port Moresby was secured.[42] These attacks did not occur, however, as the landings at Port Moresby were cancelled when the Japanese carrier force was mauled in the Battle of the Coral Sea.[43]

Japanese aircraft made almost 100 raids, most of them small, against

Japanese naval aircraft operating from land bases also harassed coastal shipping in Australia's northern waters during 1942 and 1943. On 15 December 1942, four sailors were killed when the merchant ship Period was attacked off Cape Wessel in the Northern Territory. The small general purpose vessel HMAS Patricia Cam was sunk by a Japanese floatplane near the Wessel Islands on 22 January 1943 with the loss of nine sailors and civilians. Another civilian sailor was killed when the merchant ship Islander was attacked by a floatplane during May 1943.[45]

Attacks on Sydney and Newcastle (May–June 1942)

In March 1942, the Japanese military adopted a strategy of isolating Australia from the United States, which involved capturing Port Moresby in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Samoa and New Caledonia.[46] This plan was frustrated by the Japanese defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea and was postponed indefinitely after the Battle of Midway.[47]

On 27 April 1942, the submarines

On 18 May, the Eastern Detachment of the Second Special Attack Flotilla left Truk Lagoon under the command of Captain Hankyu Sasaki. Sasaki's force comprised I-22, I-24 and I-27. Each submarine was carrying a midget submarine.[51] After the intelligence gathered by I-21 and I-29 was assessed, the three submarines were ordered on 24 May to attack Sydney.[52] The three submarines of the Eastern Detachment rendezvoused with I-21 and I-29 35 mi (30 nmi; 56 km) off Sydney on 29 May.[53] In the early hours of 30 May, I-21's floatplane conducted a reconnaissance flight over Sydney Harbour that confirmed the concentration of Allied shipping sighted by I-29's floatplane was still present and remained a worthwhile target.[54]

On the night of 31 May, three midget submarines were launched from the Japanese force outside the Sydney Heads. Two of the submarines (Midget No. 22 and Midget A, also known as Midget 24) successfully penetrated the incomplete Sydney Harbour defences. Only Midget A actually attacked Allied shipping in the harbour, firing two torpedoes at the American heavy cruiser USS Chicago. These torpedoes missed Chicago but sank the depot ship HMAS Kuttabul, killing 21 seamen on board, and seriously damaged the Dutch submarine K IX. All of the Japanese midget submarines were lost. Midget No. 22 and Midget No. 27 were destroyed by the Australian defenders and Midget A was scuttled by her crew after leaving the harbour.[55]

Following this raid, the Japanese submarine force operated off Sydney and Newcastle and sank the coaster

Further Japanese submarine patrols (July–August 1942)

The Australian authorities received only a brief break in the submarine threat. In July 1942, three submarines (I-11, I-174 and I-175) from Submarine Squadron 3 commenced operations off the East Coast. These submarines sank five ships (including the small fishing trawler Dureenbee) and damaged several others during July and August. In addition, I-32 conducted a patrol off the southern coast of Australia while en route from New Caledonia to Penang, though it did not sink any ships in this area. Following the withdrawal of this force in August, no further submarine attacks were made against Australia until January 1943.[59]

Japanese submarines sank 17 ships in Australian waters in 1942, 14 of which were near the Australian coast. This offensive did not have a serious impact on the Allied war effort in the South West Pacific or the Australian economy. Nevertheless, by forcing ships sailing along the east coast to travel in convoy the Japanese submarines reduced the efficiency of Australian coastal shipping. This translated into between 7.5% and 22% less tonnage being transported between Australian ports each month (no accurate figures are available and the estimated figure varied between months).[60] The convoys were effective with no ship travelling as part of a convoy being sunk in Australian waters during 1942.[61]

1943

East coast submarine patrols (January–June 1943)

Japanese submarine operations against Australia in 1943 began when I-10 and I-21 sailed from Rabaul on 7 January to reconnoitre the Nouméa and Sydney areas respectively. I-21 arrived off New South Wales just over a week later. It operated along the east coast until late February, sinking six ships. This was the most successful submarine patrol conducted in Australian waters during World War II.[62] I-21's floatplane conducted a successful reconnaissance of Sydney Harbour on 19 February.[63]

I-6 and I-26 entered Australian waters in March. I-6 laid nine German-supplied acoustic mines in the approaches to Brisbane. This minefield was discovered by the sloop HMAS Swan and neutralised before any ships were sunk.[64] Although I-6 returned to Rabaul after laying her mines, the Japanese submarine force in Australian waters was expanded in April when I-11, I-177, I-178 and I-180 of Submarine Squadron 3 arrived off the east coast and joined I-26. This force sought to attack reinforcement and supply convoys travelling between Australia and New Guinea.[65]

As the Japanese force was too small to cut off all traffic between Australia and New Guinea, the squadron commander widely dispersed his submarines between the Torres Strait and Wilson's Promontory with the goal of tying down as many Allied ships and aircraft as possible. This offensive continued until June, and the five Japanese submarines sank nine ships and damaged several others.

The single greatest loss of life resulting from a submarine attack in Australian waters occurred in the early hours of 14 May when I-177 torpedoed and sank the Australian

The Japanese submarine offensive against Australia was broken off in July when the submarines were redeployed to counter Allied offensives

Shelling of Port Gregory (January 1943)

Only a single Japanese submarine was dispatched against the Australian west coast during the first half of 1943. On 21 January,

After a six-day voyage southward, I-165 reached

I-165 returned twice to Australian waters. In September 1943, she made an uneventful reconnaissance of the north west coast. I-165 conducted another reconnaissance patrol off north western Australian between 31 May and 5 July 1944. This was the last time a Japanese submarine entered Australian waters.[77]

German raider Michel (June 1943)

1944–1945

Landing in the Kimberley (January 1944)

While the Japanese government never adopted

Japanese operations in the Indian Ocean (March 1944)

In February 1944, the

On 1 March, a Japanese squadron led by the heavy cruiser

While the Japanese raid into the Indian Ocean was not successful, associated Japanese shipping movements provoked a major Allied response. In early March 1944, Allied intelligence reported that two battleships escorted by destroyers had left Singapore in the direction of Surabaya and an American submarine made radar contact with two large Japanese ships in the Lombok Strait. The Australian Chiefs of Staff Committee reported to the Government on 8 March that there was a possibility that these ships could have entered the Indian Ocean to attack Fremantle. In response to this report, all ground and naval defences at Fremantle were fully activated, all shipping was ordered to leave Fremantle and several RAAF squadrons were redeployed to bases in Western Australia.[85]

This alert proved to be a false alarm. The Japanese ships detected in the Lombok Strait were actually the light cruisers Kinu and Ōi which were covering the return of the surface raiding force from the central Indian Ocean. The alert was lifted at Fremantle on 13 March and the RAAF squadrons began returning to their bases in eastern and northern Australia on 20 March.[86]

The German submarine offensive (September 1944 – January 1945)

On 14 September 1944, the commander of the Kriegsmarine—

Due to the difficulty of maintaining German submarines in Japanese bases, the boats were not ready to depart from their bases in Penang and Batavia until early October. By this time, the Allies had intercepted and decoded German and Japanese messages describing the operation and were able to vector submarines onto the German boats.[89] The Dutch submarine Zwaardvisch sank U-168 on 6 October near Surabaya[90] and the American submarine USS Flounder sank U-537 on 10 November near the northern end of the Lombok Strait.[90] Due to the priority accorded to the Australian operation, U-196 was ordered to replace U-168.[91] U-196 disappeared in the Sunda Strait some time after departing from Penang on 30 November. The cause of U-196's loss is unknown, and was likely due to either an accident or a mechanical fault.[92][93]

The only surviving submarine of the force assigned to attack Australia—U-862, under Korvettenkapitän Heinrich Timm—had left Kiel in May 1944 and reached Penang on 9 September, sinking five merchantmen on the way. It departed Batavia on 18 November 1944, and arrived off the south west tip of Western Australia on 26 November. The submarine had great difficulty finding targets as the Australian naval authorities, warned of U-862's approach, had directed shipping away from the routes normally used. U-862 unsuccessfully attacked the Greek freighter Ilissos off the South Australian coast on 9 December, with bad weather spoiling both the attack and subsequent Australian efforts to locate the submarine.[94][95]

Following her attack on Ilissos, U-862 continued east along the Australian coastline, and entered the Pacific after passing to the south of Tasmania. The submarine achieved its first success on this patrol when it attacked the United States-registered Liberty ship Robert J. Walker off the southern coast of New South Wales on 24 December 1944. The ship sank the following day. U-862 evaded an intensive search by Australian aircraft and warships and departed for New Zealand.[96]

As U-862 did not find any worthwhile targets off New Zealand, the submarine's commander planned to return to Australian waters in January 1945 and operate to the north of Sydney. U-862 was ordered to break off her mission in mid-January, however, and return to Batavia.[97] On its return voyage, the submarine sank another U.S. Liberty ship—Peter Silvester—approximately 820 nmi (940 mi; 1,520 km) southwest of Fremantle on 6 February 1945. Peter Silvester was the last Allied ship to be sunk by the Axis in the Indian Ocean during the war.[98] U-862 arrived in Batavia in mid-February 1945 and is the only Axis ship known to have operated in Australian waters during 1945.[99]

While Allied naval authorities were aware of the approach of the German strike force and were successful in sinking two of the four submarines dispatched, efforts to locate and sink U-862 once she reached Australian waters were continually hampered by a lack of suitable ships and aircraft and a lack of personnel trained and experienced in anti-submarine warfare.[100] As southern Australia was thousands of kilometres behind the active combat front in South-East Asia and had not been raided for several years, there were few anti-submarine assets available in this area in late 1944 and early 1945.[101]

Conclusions

Casualties

Japanese submarines and U-862 sank 30 ships in the area covered by the Australia Station during World War II. These ships had a combined tonnage of 150,984 gross register tons (427,540 m3).[98] Nine other ships were damaged by Japanese submarines.[103] German surface raiders sank seven ships in Australian waters and captured another. Another merchant vessel was damaged by a mine.[103]

The numbers of casualties resulting from German and Japanese attacks in Australian waters differ between sources. An unknown number of deaths and injuries were also caused by war-related accidents such as collisions between ships sailing together in convoys.[17] The official history of Australia's role in World War II states that a total of 654 people were killed on board the vessels sunk by submarines, including approximately 200 Australian merchant seamen. It does not identify the number of people wounded in these attacks.[98] The Seamen's Union of Australia's post-war history put the number of Australian merchant seaman killed at 386, and research by the Australian War Memorial had by 1989 identified 520 Australian merchant seaman who had died.[17]

Evidence on military casualties is fragmentary. Fatalities on RAN ships from enemy action in Australian waters include 645 men on Sydney, 19 from Kuttabul, 7 on board ships attacked at Darwin and 5 killed on Patricia Cam. Several escort vessels also suffered fatalities that resulted from accidents.[104] In his PhD thesis David Joseph Wilson estimated that at least 104 members of the RAAF were killed during maritime patrol and anti-submarine operations off the Australian coast, with at least 23 aircraft being destroyed.[105]

Assessment

While the scale of the Axis naval offensive directed against Australia was small compared to other naval campaigns of the war such as the Battle of the Atlantic, they were still "the most comprehensive and widespread series of offensive operations ever conducted by an enemy against Australia".[106] Due to the limited size of the Australian shipping industry and the importance of sea transport to the Australian economy and Allied military in the South West Pacific, even modest shipping losses had the potential to seriously damage the Allied war effort in the South West Pacific.[33]

Despite the vulnerability of the Australian shipping industry, the Axis attacks did not seriously affect the Australian or Allied war effort. While the German surface raiders which operated against Australia caused considerable disruption to merchant shipping and tied down Allied naval vessels, they did not sink many ships and only operated in Australian waters for a few short periods.[4] The effectiveness of the Japanese submarine campaign against Australia was limited by the inadequate numbers of submarines committed and flaws in Japan's submarine doctrine. The submarines were, however, successful in forcing the Allies to devote considerable resources to protecting shipping in Australian waters between 1942 and late 1943.[106] The institution of coastal convoys between 1942 and 1943 may have also significantly reduced the efficiency of the Australian shipping industry during this period.[107]

The performance of the Australian and Allied forces committed to the defence of shipping on the Australia station was mixed. While the threat to Australia from Axis raiders was "anticipated and addressed",[108] only a small proportion of the Axis ships and submarines which attacked Australia were successfully located or engaged. Several German raiders operated undetected within Australian waters in 1940 as the number of Allied warships and aircraft available were not sufficient to patrol these waters[109] and the loss of HMAS Sydney was a high price to pay for sinking Kormoran in 1941. While the Australian authorities were quick to implement convoys in 1942 and no convoyed ship was sunk during that year, the escorts of the convoys that were attacked in 1943 were not successful in either detecting any submarines before they launched their attack or successfully counter-attacking these submarines.[110] Factors explaining the relatively poor performance of Australian anti-submarine forces include their typically low levels of experience and training, shortages of anti-submarine warfare assets, problems with co-ordinating searches and the poor sonar conditions in the waters surrounding Australia.[111] Nevertheless, "success in anti-submarine warfare cannot be measured simply by the total of sinkings achieved" and the Australian defenders may have successfully reduced the threat to shipping in Australian waters by making it harder for Japanese submarines to carry out attacks.[111][112]

Remembrance

The naval operations in Australian waters during World War II were not publicised during the war, and have received relatively little attention from historians.[110] This forms part of broader limitations in the literature on the defence of the Australian mainland during the war, which includes a lack of any published works providing a comprehensive single-volume history of the topic.[113] The Australian official history series cover the campaigns from the viewpoint of each service separately, with the naval volumes providing an account of each of the sinkings in Australian waters throughout the war.[2][114] The official history does not cover the experiences of the Merchant Navy, however.[17] A large number of specialist Australian works discuss various aspects of the operations, and the history of the Seamen's Union of Australia covers the experiences of civilian mariners.[115][18] Coverage of the Japanese submarine campaign against Australia in Japanese-language works is also limited.[106]

There was little official recognition of the role played by the Merchant Navy in the years after the war.[18] Merchant seaman were eventually issued with Merchant Navy War Service medals and were permitted to join Anzac Day marches from the mid-1970s. The surviving members of the Merchant Navy received the same access to military pensions as former service personnel in 1994.[17] As of 2012, three major memorials had been erected to Australian merchant seamen who were killed in Australian waters during World War II.[116] In 1950 BHP established a memorial to the seamen killed on board the ships it operated. This has since been moved to the banks of the Hunter River in central Newcastle.[17] The national Merchant Seaman Memorial at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra was dedicated in 1990. Another memorial is located at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney.[116] A number of small memorials to seamen killed in the war are located across Australia.[17] Since 2008, Merchant Navy Day has been commemorated annually on 3 September and Battle for Australia Day has been observed on the first Wednesday of each September.[117][118]

There are also several memorials to the military personnel killed in Australian waters. A memorial to HMAS Sydney was dedicated at Geraldton in November 2001.

See also

Notes

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b "Enemy Action on the Australian Station 1939–45". Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 51.

- ^ a b Cooper 2001.

- ^ Hague 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 69–70, 259, 277.

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 125, 527–530.

- ^ Stephens 2006, p. 146.

- ^ Straczek, J.H. "RAN in the Second World War". Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ Odgers 1968, p. 349.

- ^ Palazzo 2001, p. 136.

- ^ Palazzo 2001, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 420.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miles 2012.

- ^ a b c Cahill 1991.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 330–332.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 261.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 262.

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 270–276.

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 276–279.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 281.

- ^ a b Gill 1957, p. 410.

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b Gill 1957, p. 284.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 283.

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 446–447.

- ^ "The action between HMAS Sydney and the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, 19 November 1941". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Frame 1993, p. 177.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 197–198.

- ^ a b Stevens 2005, p. 330.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 183.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 183–184.

- ^ McCarthy, M., (1990). "Japanese Submarine I 124". Report, Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Maritime Museum, No 43

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Waters 1956, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Lewis 2003, pp. 63–71.

- ^ Morison 2001, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Battle of the Coral Sea, 4–8 May 1942: Summary". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 264–266.

- ^ Horner 1993, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Horner 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, p. 163.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, p. 165.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, p. 171.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 185–193.

- ^ Nichols 2006, pp. 26–29.

- ^ a b Stevens 2005, p. 195.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, p. 291.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 201.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 205.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 268–272.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 253–262.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Crowhurst 2013, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2001). "IJN Submarine I-178: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 277–285.

- ^ Frame 2004, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 246.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 246–248.

- ^ a b Stevens 2002.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Jenkins 1992, p. 286.

- ^ Gill 1968, p. 297.

- ^ "Australia under attack: The battle for Australia". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Frei 1991, p. 171.

- ^ Frei 1991, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Frei 1991, p. 174.

- ^ Odgers 1968, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 388–390.

- ^ Odgers 1968, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 262.

- ^ Stevens 1997, p. 119.

- ^ Stevens 2005, pp. 262–263, 266–267.

- ^ a b Kemp 1997, p. 221.

- ^ Stevens 1997, p. 124.

- ^ Kemp 1997, p. 225.

- ^ Stevens 1997, p. 140.

- ^ Stevens 1997, pp. 147–151.

- ^ Cooke 2000, pp. 426–428.

- ^ Stevens 1997, pp. 148–173.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 278.

- ^ a b c Gill 1968, p. 557.

- ^ Stevens 1997, p. 222.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 258.

- ^ Stevens 1997, pp. 164–165.

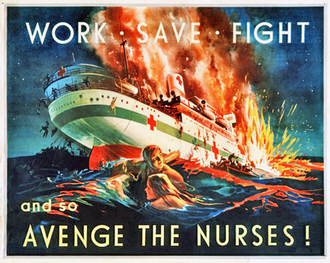

- ^ Caption to the copy of this poster on display in the Second World War gallery of the Australian War Memorial

- ^ a b "Ship Engagements in Australian Waters 1940–45". Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 711–713.

- ^ Wilson 2003, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Stevens 2001.

- ^ Stevens 2005, p. 334.

- ^ Seapower Centre – Australia 2005, p. 179.

- ^ Long 1973, p. 33.

- ^ a b Stevens 2005, p. 331.

- ^ a b Stevens 2005, p. 281.

- ^ Odgers 1968, p. 153.

- ^ Arnold 2013, p. 5.

- ^ Arnold 2013, pp. 6–11.

- ^ Arnold 2013, pp. 11–14.

- ^ a b Smith 2012, p. 7.

- ^ "Service marks merchant navy contribution". ABC News. 3 September 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Blenkin, Max (26 June 2008). "'Battle for Australia' Day in September". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "H.M.A.S. Sydney II Memorial". Monument Australia. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Döbler, Tim; Perryman, John (2021). "Commemorating the Crews of HMAS Sydney (II) and HSK Kormoran at Home and Abroad". Semaphore. Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Memorials". M24 Midget Submarine. Heritage NSW. 28 May 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "I-124 Japanese Submarine Memorial Plaque". Australian Japanese Association of the Northern Territory. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Cemeteries in Australia". Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Sydney Memorial". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

References

- Arnold, Anthony (2013). A Slim Barrier: The Defence of Mainland Australia 1939–1945 (PhD thesis). University of New South Wales.

- Cahill, Rowan (March–August 1991). "An Issue of Neglect (Merchant Marine Memorial)". The Hummer. 31 (2). Australian Society for the Study of Labour History.

- Cooke, Peter (2000). Defending New Zealand: Ramparts on the Sea 1840–1950s (Part I). Wellington: Defence of New Zealand Study Group. ISBN 0-473-06833-8.

- Cooper, Alistair (2001). "Raiders and the Defence of Trade: The Royal Australian Navy in 1941". Remembering 1941: 2001 History Conference. Australian War Memorial.

- Crowhurst, Geoff (2013). "Who Sank I-178?" (PDF). The Navy. 75 (1): 27–30. ISSN 1322-6231.

- ISBN 0-340-58468-8.

- Frame, Tom (2004). No Pleasure Cruise: The Story of the Royal Australian Navy. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-233-4.

- Frei, Henry P. (1991). Japan's Southward Advance and Australia. From the Sixteenth Century to World War II. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84392-1.

- OCLC 250134639.

- OCLC 65475.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Royal Australian Air Force, 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Vol. Series 3 – Air. Volume I. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 696244290.

- Hague, Arnold (2000). The Allied Convoy System 1939–1945: Its Organization, Defence and Operation. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-019-3.

- Horner, David (May 1993). "Defending Australia in 1942". War & Society. 11 (1): 1–20. .

- Jenkins, David (1992). Battle Surface: Japan's Submarine War Against Australia 1942–44. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 0-09-182638-1.

- Kemp, Paul (1997). U-Boats Destroyed: German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-321-5.

- ISBN 0-9577351-0-3.

- ISBN 0-642-99375-0.

- Miles, Patricia (2012). "War casualties and the Merchant Navy". New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage.

- ISBN 0-252-06995-1.

- Nichols, Robert (2006). "The Night the War Came to Sydney". Wartime (33). Australian War Memorial. ISSN 1328-2727.

- OCLC 1990609.

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551506-4.

- Seapower Centre – Australia (2005). The Navy Contribution to Australian Maritime Operations. Canberra: Defence Publishing Service. ISBN 0-642-29615-4.

- Smith, Tim (2012). "World War Two Shipwrecks and Submarine Attacks in NSW Waters 1940–1944" (PDF). Office of Environment and Heritage, New South Wales Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2022.

- Stephens, Alan (2006). The Royal Australian Air Force (Paperback ed.). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19555-541-7.

- Stevens, David (1997). U-boat Far from Home: The Epic Voyage of U 862 to Australia and New Zealand. St. Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-267-2.

- Stevens, David (2001). "Japanese submarine operations against Australia 1942–1944". Australia-Japan Research Project. Australian War Memorial.

- Stevens, David (Autumn 2002). "Forgotten assault". Wartime (18). Australian War Memorial. ISSN 1328-2727.

- Stevens, David (2005). A Critical Vulnerability: The Impact of the Submarine Threat on Australia's Maritime Defence 1915–1954 (PDF). Canberra: Sea Power Centre Australia. ISBN 0-642-29625-1.

- Waters, Sydney D. (1956). The Royal New Zealand Navy. OCLC 568681359.

- Wilson, David Joseph (2003). The Eagle and the Albatross: Australian Aerial Maritime Operations 1921–1971 (PhD thesis). Sydney: University of New South Wales. OCLC 648818143.

Further reading

- Carruthers, Steven L. (1982). Australia Under Siege: Japanese Submarine Raiders, 1942. Sydney: Solus Books. ISBN 0-9593614-0-5.

- Fitzpatrick, Brian; Cahill, Rowan J. (1981). The Seamen's Union of Australia, 1872–1972: A History. Sydney: Seamen's Union of Australia. ISBN 0959871306.

- Hiromi, Tanaka (April 1997). "The Japanese Navy's operations against Australia in the Second World War, with a commentary on Japanese sources". Journal of the Australian War Memorial (30). ISSN 1327-0141.

- Jedrzejewski, Marcin. "Monsun boats: U-boats in the Indian Ocean and the Far East". uboat.net.

- Jones, Terry; Carruthers, Steven (2013). A Parting Shot: Shelling of Australia by Japanese Submarines 1942. Narrabeen, NSW: Casper Publications. ISBN 9780977506347.

- Marcus, Alex (1986). "DEMS? What's DEMS?": The Story of the Men of the Royal Australian Navy Who Manned Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships During World War II. Brisbane: Boolarong. ISBN 0864390122.

- McGirr, Jocelyn (1989). Inquiry into the needs of Australian Mariners, Commonwealth and Allied Veterans and Allied Mariners. Woden, Australian Capital Territory: Repatriation Commission. OCLC 220789043.

- Stevens, David (1993). "I-174: The last Japanese submarine off Australia". Journal of the Australian War Memorial (22). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISSN 0729-6274.

- Stevens, David (September–October 1993). "The War Cruise of the 1–6, March 1943" (PDF). Australian Defence Force Journal (102). ISSN 1320-2545.