Genome evolution

Genome evolution is the process by which a genome changes in structure (sequence) or size over time. The study of genome evolution involves multiple fields such as structural analysis of the genome, the study of genomic parasites, gene and ancient genome duplications, polyploidy, and comparative genomics. Genome evolution is a constantly changing and evolving field due to the steadily growing number of sequenced genomes, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic, available to the scientific community and the public at large.

History

Since the first sequenced genomes became available in the late 1970s,

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes

Prokaryotes

Prokaryotic genomes have two main mechanisms of evolution: mutation and horizontal gene transfer.[3] A third mechanism, sexual reproduction, is prominent in eukaryotes and also occurs in bacteria. Prokaryotes can acquire novel genetic material through the process of bacterial conjugation in which both plasmids and whole chromosomes can be passed between organisms. An often cited example of this process is the transfer of antibiotic resistance utilizing plasmid DNA.[4] Another mechanism of genome evolution is provided by transduction whereby bacteriophages introduce new DNA into a bacterial genome. The main mechanism of sexual interaction is natural genetic transformation which involves the transfer of DNA from one prokaryotic cell to another though the intervening medium. Transformation is a common mode of DNA transfer and at least 67 prokaryotic species are known to be competent for transformation.[5]

Genome evolution in bacteria is well understood because of the thousands of completely sequenced bacterial genomes available. Genetic changes may lead to both increases or decreases of genomic complexity due to adaptive genome streamlining and purifying selection.[6] In general, free-living bacteria have evolved larger genomes with more genes so they can adapt more easily to changing environmental conditions. By contrast, most parasitic bacteria have reduced genomes as their hosts supply many if not most nutrients, so that their genome does not need to encode for enzymes that produce these nutrients themselves.[7][page needed]

| Characteristic | E.coli genome | Human genome |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size (base pairs) | 4.6 Mb | 3.2 Gb |

| Genome Structure | Circular | Linear |

| Number of chromosomes | 1 | 46 |

| Presence of Plasmids | Yes | No |

| Presence of Histones | No | Yes |

| DNA segregated in the nucleus | No | Yes |

| Number of genes | 4,288 | 20,000 |

| Presence of Introns | No* | Yes |

| Average Gene Size | 700 bp | 27,000 bp |

Eukaryotes

Eukaryotic genomes are generally larger than that of the prokaryotes. While the E. coli genome is roughly 4.6Mb in length,

Genome size

Genome size can increase by

An example of increasing genome size over time is seen in filamentous plant pathogens. These plant pathogen genomes have been growing larger over the years due to repeat-driven expansion. The repeat-rich regions contain genes coding for host interaction proteins. With the addition of more and more repeats to these regions the plants increase the possibility of developing new virulence factors through mutation and other forms of genetic recombination. In this way it is beneficial for these plant pathogens to have larger genomes.[16]

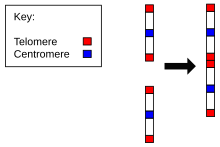

Chromosomal evolution

The evolution of genomes can be impressively shown by the change of chromosome number and structure over time. For instance, the ancestral chromosomes corresponding to chimpanzee chromosomes 2A and 2B fused to produce human chromosome 2. Similarly, the chromosomes of more distantly related species show chromosomes that have been broken up into more parts over the course of evolution. This can be demonstrated by Fluorescence in situ hybridization.[17]

Mechanisms

Gene duplication

Whole genome duplication

Similar to gene duplication, whole genome duplication is the process by which an organism's entire genetic information is copied, once or multiple times which is known as polyploidy.[20] This may provide an evolutionary benefit to the organism by supplying it with multiple copies of a gene thus creating a greater possibility of functional and selectively favored genes. However, tests for enhanced rate and innovation in teleost fishes with duplicated genomes compared with their close relative holostean fishes (without duplicated genomes) found that there was little difference between them for the first 150 million years of their evolution.[21]

In 1997, Wolfe & Shields gave evidence for an ancient duplication of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (

Transposable elements

Mutation

Spontaneous

Pseudogenes

Often a result of spontaneous

Often cited examples of pseudogenes within the human genome include the once functional

Similarly, bacterial pseudogenes commonly arise from adaptation of free-living bacteria to parasitic lifestyles, so that many metabolic genes become superfluous as these species become adapted to their host. Once a parasite obtains nutrients (such as amino acids or vitamins) from its host it has no need to produce these nutrients itself and often loses the genes to make them.[citation needed]

Exon shuffling

Genome reduction and gene loss

Many species exhibit genome reduction when subsets of their genes are not needed anymore. This typically happens when organisms adapt to a parasitic life style, e.g. when their nutrients are supplied by a host. As a consequence, they lose the genes needed to produce these nutrients. In many cases, there are both free living and parasitic species that can be compared and their lost genes identified. Good examples are the genomes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae, the latter of which has a dramatically reduced genome (see figure under pseudogenes above).

Another beautiful example are

Speciation

A major question of evolutionary biology is how genomes change to create new species. Speciation requires changes in behavior, morphology, physiology, or metabolism (or combinations thereof). The evolution of genomes during speciation has been studied only very recently with the availability of next-generation sequencing technologies. For instance, cichlid fish in African lakes differ both morphologically and in their behavior. The genomes of 5 species have revealed that both the sequences but also the expression pattern of many genes has quickly changed over a relatively short period of time (100,000 to several million years). Notably, 20% of duplicate gene pairs have gained a completely new tissue-specific expression pattern, indicating that these genes also obtained new functions. Given that gene expression is driven by short regulatory sequences, this demonstrates that relatively few mutations are required to drive speciation. The cichlid genomes also showed increased evolutionary rates in microRNAs which are involved in gene expression.[39][40]

Gene expression

Mutations can lead to changed gene function or, probably more often, to changed gene expression patterns. In fact, a study on 12 animal species provided strong evidence that tissue-specific gene expression was largely conserved between orthologs in different species. However, paralogs within the same species often have a different expression pattern. That is, after duplication of genes they often change their expression pattern, for instance by getting expressed in another tissue and thereby adopting new roles.[41]

Composition of nucleotides (GC content)

The genetic code is made up of sequences of four

Evolving translation of genetic code

Amino acids are made up of three base long

De novo origin of genes

Novel genes can arise from

Origin of life and the first genomes

In order to understand how the genome arose, knowledge is required of the chemical pathways that permit formation of the key building blocks of the genome under plausible prebiotic conditions. According to the RNA world hypothesis free-floating ribonucleotides were present in the primitive soup. These were the fundamental molecules that combined in series to form the original RNA genome. Molecules as complex as RNA must have arisen from small molecules whose reactivity was governed by physico-chemical processes. RNA is composed of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, both of which are necessary for reliable information transfer, and thus Darwinian natural selection and evolution. Nam et al.[52] demonstrated the direct condensation of nucleobases with ribose to give ribonucleosides in aqueous microdroplets, a key step leading to formation of the RNA genome. Also, a plausible prebiotic process for synthesizing pyrimidine and purine ribonucleotides leading to genome formation using wet-dry cycles was presented by Becker et al.[53]

See also

- De novo gene birth

- Exon shuffling

- Gene fusion

- Gene duplication

- Horizontal gene transfer

- Mobile genetic elements

References

- S2CID 4289674.

- PMID 11181995.

- PMID 22144148.

- PMID 22831841.

- PMID 17997281.

- PMID 18948295.

- ISBN 978-0321929150.

- PMID 12403467.

- PMID 9278503.

- PMID 15496913.

- PMID 11325054.

- PMID 11913657.

- PMID 21162636.

- PMID 11826475.

- PMID 11043978.

- S2CID 6169712.

- PMID 36207754.

- .

- PMID 15568988.

- PMID 22566086.

- PMID 27671652.

- PMID 9192896.

- S2CID 26130646.

- S2CID 5799005.

- S2CID 32132898.

- PMID 15680506.

- PMID 22716230.

- ^ S2CID 4307207.

- PMID 21940196.

- S2CID 10868777.

- PMID 28555784.

- PMID 21398401.

- S2CID 29725250.

- PMID 11701659.

- PMID 15313546.

- PMID 14642747.

- S2CID 2266380.

- PMID 24167248.

- PMID 25186727.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link - PMID 25186726.

- PMID 28030541.

- PMID 21821053.

- PMID 12547511.

- PMID 25225383.

- PMID 16777968.

- PMID 18550802.

- PMID 18493065.

- PMID 19240804.

- PMID 19726446.

- PMID 22102831.

- PMID 30809245.

- ^ Nam I, Nam HG, Zare RN. Abiotic synthesis of purine and pyrimidine ribonucleosides in aqueous microdroplets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018 Jan 2;115(1):36-40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718559115. Epub 2017 Dec 18. PMID 29255025; PMCID: PMC5776833

- ^ Becker S, Feldmann J, Wiedemann S, Okamura H, Schneider C, Iwan K, Crisp A, Rossa M, Amatov T, Carell T. Unified prebiotically plausible synthesis of pyrimidine and purine RNA ribonucleotides. Science. 2019 Oct 4;366(6461):76-82. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2747. PMID 31604305.