History of local government in Scotland

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of the United Kingdom on the |

| Politics of Scotland |

|---|

|

The History of local government in Scotland is a complex tale of largely ancient and long established Scottish political units being replaced after the mid 20th century by a frequently changing series of different local government arrangements.

Origins

Anciently, the territory now referred to as Scotland belonged to a mixture of

The Picts were based north of the Forth–Clyde line, traditionally in seven kingdoms:

- Cat (the far north)

- )

- )

- Fib(the Fife peninsula)

- Fotla (an expanded Atholl)

- Fortriu (the areas to the north and west of the Grampians, including the Great Glen, and extending to the Atlantic coast, and as far north as the Dornoch Firth)

- Fidach (unknown location).

In later legends Albanactus, the legendary founder of Scotland, had seven sons, who each founded a kingdom. De Situ Albanie enumerates the kingdoms in two lists, the first of which locates the seventh kingdom between the Forth and the Earn, while the second additionally replaces Cat with the area that became Dalriada.

The Cumbrians were based in the southwest, in two principal kingdoms:

- Rheged (the lands bordering the Solway Firth, stretching as far as modern Cumbria)

- Strathclyde

The Angles were based in the southeast, in the

- Lothian (bordering the Firth of Forth)

- Bernicia (bordering the North Sea, as far south as the Tees)

When the Irish group , which they organised into four geographic kin-groups:

- Cenél nÓengusa (Islay)

- Cenél Loairn (the area around the Firth of Lorn, including Mull)

- Cenél nGabráin (Kintyre and Knapdale)

- Cenél Comgaill (Cowal and the Isle of Bute)

Alba

For reasons which are extremely opaque to historical enquiry, most of the Pictish lands became a Scotii kingdom based at

Northumbrian pressure caused Rheged to collapse, establishing Galloway as an independent state. Strathclyde took the opportunity created by Rheged's collapse to expand towards the southeast, into what is now northern Cumbria. Records are unclear, but it seems that Scotii raids led to Galloway submitting to the authority of Alba, and the transfer of Carrick from Strathclyde to Galloway.

- Norðreyjar, divided into:

- Suðreyjar (the Hebrides, Arran, and the Isle of Man)

Norse invaders also besieged Dumbarton Rock, the capital of Strathclyde, eventually causing its defeat. As a result, Dunbarton Rock was abandoned, and Strathclyde moved its capital upriver, to Partick. Alba took the opportunity to seize the now-undefended area around Loch Lomond. Similarly, the weakening of Northumbria enabled Alba to push south and take over the area around Stirling.

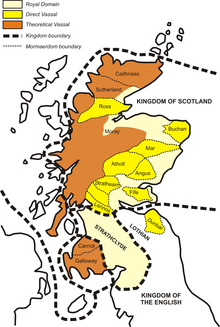

By the 10th century, the governance of the area now known as Scotland thus broke down as follows:

| Former ethnicity | Former area | Outcome | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pictish | Cat | Caithness | Norse jarldom |

| Sutherland | Norse jarldom | ||

| Ce | Buchan | Mormaerdom

| |

| Banff | Stewardry | ||

Mar

|

Mormaerdom

| ||

| Circinn | Mearns | Stewardry | |

| Angus | Mormaerdom

| ||

| Fib | Fothriff | Stewardry | |

| Fife | Mormaerdom

| ||

| Fotla | Gowrie | Stewardry | |

| Atholl | Mormaerdom

| ||

| (possibly Fidach) | Menteith | Mormaerdom

| |

| Strathearn | Mormaerdom

| ||

| Fortriu | Ross | Mormaerdom

| |

Moray

|

Quasi-independent | ||

| Cumbric | (Scottish) Rheged | Galloway | Quasi-independent vassal |

| Strathclyde | |||

| Lennox | Mormaerdom

| ||

| Strathclyde (remainder) | Independent | ||

| Anglian | Lothian | Stirling | Stewartry |

| Lothian (remainder) | English ealdormandom | ||

| (Scottish) Bernicia | (Scottish) Bernicia | English ealdormandom | |

| Gaelic | nÓengusa | Islay | Norse jarldom |

| Loairn | Mull | Norse jarldom | |

| Lorn | Quasi-independent vassal | ||

| nGabráin | Argyll | Quasi-independent vassal | |

| Comgaill |

Middle ages

Provinces

In the

The

Founding of the Burghs

The first

Burghs were typically settlements under the protection of a castle and usually had a market place, with a widened high street or junction, marked by a mercat cross, beside houses for the burgesses and other inhabitants.[7] 16 royal burghs can trace their foundation to David I traced to the reign of David I (1124–53)[9] and there is evidence of 55 burghs by 1296.[10] In addition to the major royal burghs, the late Middle Ages saw the proliferation of baronial and ecclesiastical burghs, with 51 created between 1450 and 1516. Most of these were much smaller than their royal counterparts. Excluded from foreign trade, they acted mainly as local markets and centres of craftsmanship.[8] Burghs were centres of basic crafts, including the manufacture of shoes, clothes, dishes, pots, joinery, bread and ale, which would normally be sold to "indwellers" and "outdwellers" on market days.[7] In general, burghs carried out far more local trading with their hinterlands, on which they relied for food and raw materials, than trading nationally or abroad.[11]

Early Modern Scotland

From the sixteenth century, the central government became increasingly involved in local affairs. The

From the seventeenth century the function of shires expanded from judicial functions into wider local administration, From this point shires came to be regarded as the main division of the country in preference to the former provinces.

The parish also became an important unit of local government, pressured by Justices in the early eighteenth century, it became responsible for taking care of the destitute in periods of famine, like that in 1740, in order to prevent the impoverished from taking to the roads and causing general disorder.

From the eighteenth century the shires (used for administration) began to diverge from the sheriffdoms (used for judicial functions) (see Historical development of Scottish sheriffdoms).[18]

Modern era

|

As a result of the dual system of local government,

Between 1890 and 1929, there were parish councils and town councils, but with the passing of the

This system was further refined by the passing of the

A Royal Commission on Local Government in Scotland in 1969 (the

The system was only to last for 21 years as with the passing of the

Local Government Acts

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

- Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889

- Local Government (Scotland) Act 1894

- Local Government (Scotland) Act 1929

- Local Government (Scotland) Act 1947

- Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973

- Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994

- Local Government (Gaelic Names) (Scotland) Act 1997

- Local Governance (Scotland) Act 2004 - changed the election system for local authorities from first-past-the-post to single transferable vote

See also

- Counties of Scotland

- Burghs

- History of local government in the United Kingdom

- Local government areas of Scotland 1973 to 1996

References

- ISBN 0-415-12231-7, p. 179.

- ^ John of Fordun wrote that Malcolm II introduced the shire to Scotland and also the thane class. Shires are mentioned in charters by the reign of King Malcolm III, for instance that to the Church of Dunfermline, AD 1070–1093.

- ^ Wallace, James (1890). The Sheriffdom of Clackmannan: A sketch of its history with a list of its sheriffs and excerpts from the records of court compiled from public documents and other authorities with preparatory notes on the office of Sheriff in Scotland, his powers and duties. Edinburgh: James Thin. pp. 7–19.

- ^ The earliest sheriffdom south of the Forth which we know of for certain is Haddingtonshire, which is named in a charters of 1139 as Hadintunschira (Charter by King David to the church of St. Andrews of the church of St. Mary at Haddington) and of 1141 as Hadintunshire (Charter by King David granting Clerchetune to the church of St. Mary of Haddington). In 1150 a charter refers to Madolyn Stirlingshire (Striuelinschire).(Charter by King David granting the church of Clackmannan, etc., to the Abbey of Stirling)

- ^ J Mackay, The Convention of Royal Burghs of Scotland, From its Origin down to the Completion of the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland in 1707, Co-operative Printing, Edinburgh 1884, p.2

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 98.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 136–140.

- ^ ISBN 0415278805, p. 78.

- ISBN 0198206151, pp. 38–76.

- ISBN 0333567617, pp. 122–23.

- ISBN 0748602763, pp. 41–55.

- ^ ISBN 0748602763, pp. 162-3.

- ISBN 0748602763, pp. 164-5.

- ^ Mackenzie 1810, pp.15–16

- ^ ISBN 0521891671, p. 202.

- ^ ISBN 074860233X, p. 144.

- ISBN 074860233X, pp. 80-1.

- ^ Owen Ruffhead, The statutes at large: from Magna Carta to the end of the last parliament, 1761 [i.e. 1763], M. Baskett (1765 [1763]) p. 104.

- ISBN 978-0-333-56081-5.