Lungfish

| Lungfish Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

Queensland lungfish

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Sarcopterygii |

| Clade: | Rhipidistia |

| Clade: | Dipnomorpha Ahlberg, 1991 |

| Class: | Dipnoi J. P. Müller, 1844 |

| Living families | |

Fossil taxa, see text | |

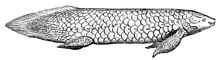

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the class Dipnoi.[1] Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, including the presence of lobed fins with a well-developed internal skeleton. Lungfish represent the closest living relatives of the tetrapods (which includes living amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals). The mouths of lungfish typically bear tooth plates, which are used to crush hard shelled organisms.

Today there are only six known species of lungfish, living in Africa, South America, and Australia, though they were formerly globally distributed. The fossil record of the group extends into the Early Devonian, over 410 million years ago. The earliest known members of the group were marine, while almost all post-Carboniferous representatives inhabit freshwater environments.[2]

Etymology

Modern Latin from the Greek δίπνοος (dipnoos) with two breathing structures, from δι- twice and πνοή breathing, breath.

Anatomy and morphology

All lungfish demonstrate an uninterrupted cartilaginous

Through convergent evolution, lungfishes have evolved internal nostrils similar to the tetrapods' choana,[4] and a brain with certain similarities to the Lissamphibian brain (except for the Queensland lungfish, which branched off in its own direction about 277 million years ago and has a brain resembling that of the Latimeria).[5]

The dentition of lungfish is different from that of any other

The modern lungfishes have a number of larval features, which suggest

Modern lungfish all have an elongate body with fleshy, paired

Lungs

Lungfish have a highly specialized

Most extant lungfish species have two lungs, with the exception of the Australian lungfish, which has only one. The lungs of lungfish are homologous to the lungs of tetrapods. As in tetrapods and bichirs, the lungs extend from the ventral surface of the esophagus and gut.[7][8]

Perfusion of water

Of extant lungfish, only the

Perfusion of air

When breathing air, the spiral valve of the conus arteriosus closes (minimizing the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood), the third and fourth gill arches open, the second and fifth gill arches close (minimizing the possible loss of the oxygen obtained in the lungs through the gills), the sixth arteriole's ductus arteriosus is closed, and the pulmonary arteries open. Importantly, during air breathing, the sixth gill is still used in respiration; deoxygenated blood loses some of its carbon dioxide as it passes through the gill before reaching the lung. This is because carbon dioxide is more soluble in water. Air flow through the mouth is tidal, and through the lungs it is bidirectional and observes "uniform pool" diffusion of oxygen.

Ecology and life history

Lungfish are

African and South American lungfish are capable of surviving seasonal drying out of their habitats by burrowing into mud and

Burrowing is seen in at least one group of fossil lungfish, the Gnathorhizidae.

Lungfish can be extremely long-lived. A

As of 2022, the oldest lungfish, and probably the oldest aquarium fish in the world is "Methuselah", an Australian lungfish 4 feet (1.2 m) long and weighing around 40 pounds (18 kg). Methuselah is believed to be female, unlike its namesake, and is estimated to be over 90 years old.[10]

Evolution

About 420 million years ago, during the Devonian, the last common ancestor of both lungfish and the tetrapods split into two separate evolutionary lineages, with the ancestor of the extant coelacanths diverging a little earlier from a sarcopterygian progenitor.[12] Youngolepis and Diabolepis, dating to 419–417 million years ago, during Early Devonian (Lochkovian), are the currently oldest known lungfish, and show that the lungfishes had adapted to a diet including hard-shelled prey (durophagy) very early in their evolution.[13] The earliest lungfish were marine. Almost all post-Carboniferous lungfish inhabit or inhabited freshwater environments. There were likely at least two transitions amongst lungfish from marine to freshwater habitats. The last common ancestor of all living lungfish likely lived sometime between the Late Carboniferous[2] and the Jurassic.[14] Lungfish remained present in the northern Laurasian landmasses into the Cretaceous period.[15]

Extant lungfish

| Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Neoceratodontidae | Neoceratodus | Queensland lungfish

|

Lepidosirenidae

|

Lepidosiren | South American lungfish |

| Protopteridae | Protopterus | Marbled lungfish |

| Gilled lungfish | ||

| West African lungfish | ||

| Spotted lungfish |

The

The

The

The

The

The

Taxonomy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

The relationship of lungfishes to the rest of the bony fish is well understood:

- Lungfishes are most closely related to Powichthys, and then to the Porolepiformes.

- Together, these taxa form the Dipnomorpha, the sister group to the Tetrapodomorpha.

- Together, these form the Rhipidistia, the sister group to the coelacanths.

Recent molecular genetic analyses strongly support a sister relationship of lungfishes and tetrapods (Rhipidistia), with coelacanths branching slightly earlier.[41][42]

The relationships among lungfishes are significantly more difficult to resolve. While Devonian lungfish had enough bone in the skull to determine relationships, post-Devonian lungfish are represented entirely by skull roofs and teeth, as the rest of the skull is

Phylogeny after Kemp, Cavin & Guinot, 2017[2]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram after Brownstein et al. 2023[14]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Ceratodus

- Lepidogalaxias salamandroides

- Polypteridae

References

- ^ "ITIS - Report: Dipnoi". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ ISSN 0031-0182.

- Greenwood Press.

- ^ "Evolution: On the evolution of internal nostrils (choanae)". Science-Week. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- PMID 25427173. 10.1371..

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - S2CID 87285937, archived from the original(PDF) on 11 June 2010

- ^ Wisenden, Brian (2003). "Chapter 24: The Respiratory System – Evolution Atlas". Human Anatomy. Pearson Education, Inc. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010.

- ^ Hilber, S.A. (2007). "Gnathostome form & function". Vertebrate Zoology Lab. U. Florida. Lab 2. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- S2CID 44787314.

- ^ a b c "Methuselah: Oldest aquarium fish lives in San Francisco and likes belly rubs". The Guardian. 26 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Chicago aquarium euthanizes 90 year-old lungfish". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Australian lungfish has largest genome of any animal sequenced so far - New Scientist

- PMID 35501345.

- ^ ISSN 0305-0270.

- S2CID 131962612.

- ^ a b Lake, John S. (1978). Australian Freshwater Fishes. Nelson Field Guides. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia Pty. Ltd. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Allen, G.R.; Midgley, S.H.; Allen, M. (2002). Knight, Jan; Bulgin, Wendy (eds.). Field Guide to the Freshwater Fishes of Australia. Perth, W.A.: Western Australia Museum. pp. 54–55.

- S2CID 225133051.

- S2CID 22778872.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst Heinrich Philipp August; Lankester, Edwin Ray; Schmitz, L. Dora (1892). The History of Creation, or, the Development of the Earth and Its Inhabitants by the Action of Natural Causes. D. Appleton. pp. 289, 422.

A popular exposition of the doctrine of evolution in general, and of that of Darwin, Goethe, and Lamarck in particular. From the 8th German edition by Ernst Haeckel

- ^ Guenther, Konrad (1931). A Naturalist in Brazil. Translated by Miall, Bernard. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 275, 399.

The record of a year's observation of her flora, her fauna, and her people.

- ^ "South American Lungfish". Animal World.

- ^ "Your Inner Fish" Neil Shubin, 2008,2009,Vintage, p.33

- ^ The differential cardio-respiratory responses to ambient hypoxia and systemic hypoxaemia in the South American lungfish, Lepidosiren paradoxa

- ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ^ Fishbase.org

- ^ Animal-World. "Marbled Lungfish". Animal World.

- S2CID 5406138.

- ^ EOL.org (Retrieved 19 February 2010.)

- ^ Fishbase.org (Retrieved 19 February 2010.)

- ^ Primitive Fishes.com Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Fishbase.org (Retrieved 25 September 2010.)

- ^ EOL.org (Retrieved 13 May 2010.)

- ^ Fishbase.org (Retrieved 13 May 2010.)

- ^ "Protopterus annectens, West African lungfish : fisheries, aquaculture". FishBase.

- ^ "West African Lungfish (Protopterus annectens annectens) - Information on West African Lungfish - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Primitivefishes.com (Retrieved May 13, 2010.) Archived 11 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Fishbase.org

- ^ Brien, P. (1959). Ethologie du Protopterus dolloi(Boulenger) et de ses larves. Signification des sacs pulmonaires des Dipneustes. Ann. Soc. R. Zool. Belg. 89, 9-48.

- ^ Poll, M. (1961). Révision systématique et raciation géographique des Protopteridae de l’Afrique centrale. Ann. Mus. R. Afr. Centr. Sér. 8. Sci. Zool. 103, 3-50.

- PMID 23598338.

- PMID 28082606.

Further reading

- Ahlberg, P.E.; Smith, M.M.; Johanson, Z. (2006). "Developmental plasticity and disparity in early dipnoan (lungfish) dentitions". Evolution and Development. 8 (4): 331–349. S2CID 28339324.

- Palmer, Douglas, ed. (1999). The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Creatures, A visual who's who of prehistoric life. Great Britain: Marshall Editions Developments Limited. p. 45.

- Schultze, H.P.; Chorn, J. (1997). "The Permo-Carboniferous genus Sagenodus and the beginning of modern lungfish". Contributions to Zoology. 61 (7): 9–70. .

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

External links

- Kemps, Anne, Dr. "Lungfish Information site". Archived from the original on 2 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dipnoiformes". Palaeos.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2006.

- "Dipnoi". University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- "Tree of life illustration showing lungfish's relation to other organisms". tellapallet.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009.

- "Lungfish video". YouTube. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021.