Psychedelia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

Psychedelia usually refers to a

A

Etymology

The term was first coined as a noun in 1956 by

Seeking a name for the experience induced by

To make this mundane world sublime,

Take half a gram of phanerothyme

To which Osmond responded:

To fathom Hell or soar angelic,

Just take a pinch of psychedelic[7]

It was on this term that Osmond eventually settled, because it was "clear, euphonious and uncontaminated by other associations."

History

This section is missing information about the origins of psychedelic culture available for copy at Acid rock#Origins and ideology. (January 2017) |

From the second half of the 1950s,

By the mid-1960s, the psychedelic life-style had already developed in California, and an entire subculture developed. This was particularly true in San Francisco, due in part to the first major underground LSD factory, established there by Owsley Stanley.[20] There was also an emerging music scene of folk clubs, coffee houses and independent radio stations catering to a population of students at nearby Berkeley, and to free thinkers that had gravitated to the city.[21] From 1964, the Merry Pranksters, a loose group that developed around novelist Ken Kesey, sponsored the Acid Tests, a series of events based around the taking of LSD (supplied by Stanley), accompanied by light shows, film projection and discordant, improvised music known as the psychedelic symphony.[22][23] The Pranksters helped popularize LSD use through their road trips across America in a psychedelically decorated school bus, which involved distributing the drug and meeting with major figures of the beat movement, and through publications about their activities such as Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968).[24]

Leary was a well-known proponent of the use of psychedelics, as was Aldous Huxley. However, both advanced widely different opinions on the broad use of psychedelics by state and civil society. Leary promulgated the idea of such substances as a panacea, while Huxley suggested that only the cultural and intellectual elite should partake of entheogens systematically.[citation needed]

In the 1960s the use of psychedelic drugs became widespread in modern Western culture, particularly in the United States and Britain. The movement is credited to Michael Hollingshead who arrived in America from London in 1965. He was sent to the U.S. by other members of the psychedelic movement to get their ideas exposure.[25] The Summer of Love of 1967 and the resultant popularization of the hippie culture to the mainstream popularized psychedelia in the minds of popular culture, where it remained dominant through the 1970s.[26]

Modern usage

The impact of psychedelic drugs on western culture in the 1960s led to

Visual art

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

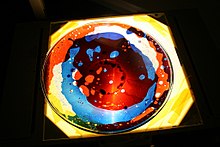

Advances in printing and photographic technology in the 1960s saw the traditional

The

Contemporary with the burgeoning San Francisco scene, a smaller but equally creative psychedelic art movement emerged in London, led by expatriate Australian pop artist

Blues rock singer Janis Joplin had a psychedelic car, a Porsche 356. The trend also extended to motor vehicles. The earliest, and perhaps most famous of all psychedelic vehicles was the famous "

Music

The fashion for psychedelic drugs gave its name to the style of psychedelia, a term describing a category of

One of the first uses of the word in the music scene of this time was in the 1964 recording of "

The

Festivals

A psychedelic festival is a gathering that promotes psychedelic music and art in an effort to unite participants in a communal psychedelic experience.[34] Psychedelic festivals have been described as "temporary communities reproduced via personal and collective acts of transgression... through the routine expenditure of excess energy, and through self-sacrifice in acts of abandonment involving ecstatic dancing often fueled by chemical cocktails."[34] These festivals often emphasize the ideals of peace, love, unity, and respect.[34] Notable psychedelic festivals include the biennial Boom Festival in Portugal,[34] Ozora Festival in Hungary, Universo Paralello in Brazil as well as Nevada's Burning Man[35] and California's Symbiosis Gathering in the United States.[36]

Conferences

In recent years there has been a resurgence in interest in psychedelic research and a growing number of conferences now take place across the globe.[37] The psychedelic research charity Breaking Convention have hosted one of the world's largest since 2011. A biennial conference in London, UK, Breaking Convention: a multidisciplinary conference on psychedelic consciousness[38] is a multidisciplinary conference on psychedelic consciousness. In the US MAPS held their first Psychedelic Science conference,[39] devoted specifically to research of psychedelics in scientific and medical fields, in 2013. In Australia, Entheogenesis Australis has been hosting the world's longest ongoing conferences around psychedelics and ethnobotany since 2004.[40]

See also

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- The Doors of Perception

- Ego death

- Erowid

- God in a Pill?

- Psychedelic era

- Psychedelia – Film about the history of psychedelic drugs

- Psychedelic fish

- Psychedelic literature

- Psychedelic plants

- Psychonautics

- Serotonergic psychedelic

- Timeline of 1960s counterculture

Notes

- ^ New York folk musician Peter Stampfel claimed to be the first to use the word "psychedelic" in a song lyric (The Holy Modal Rounders' version of "Hesitation Blues", 1963).[19]

References

- )

- )

- ^ Nicholas Murray, Aldous Huxley: A Biography, 419.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, September 2007, s.v., Etymology

- ^ A. Weil, W. Rosen. (1993), From Chocolate To Morphine: Everything You Need To Know About Mind-Altering Drugs. New York, Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 93

- ^ W. Davis (1996), "One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest". New York, Simon and Schuster, Inc. p. 120.

- PMC 381240.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (February 22, 2004). "Humphry Osmond, 86, Who Sought Medicinal Value in Psychedelic Drugs, Dies". The New York Times. p. 1001025.

- ^ W. Davis (1996), One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest. New York, Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 120.

- Carl A.P. Ruck, The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries (North Atlantic Books, 2008), pgs. 138–139

- ISBN 0-520-23033-7.

- ISBN 0-7614-4234-0, p. 30.

- ISBN 0-415-93040-5, p. 21.

- The Huffington Post, 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Out-Of-Sight! SMiLE Timeline". Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ISBN 0-226-85458-2, p. 437.

- ISBN 0-520-05193-9, p. 166.

- ISBN 0-8264-6321-5, p. 211.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 8.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, pp. 8–9.

- ISBN 0-87930-743-9, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 41 – The Acid Test: Psychedelics and a sub-culture emerge in San Francisco. [Part 1] : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Hicks 2000, p. 60.

- ISBN 1-84755-909-3, p. 87.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2007). "Spontaneous Underground: An Introduction to Psychedelic Scenes, 1965–1968". In Christopher Grunenberg, Jonathan Harris (ed.). Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s (8 ed.). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 63–98.

- ^ "The Summer of Love was more than hippies and LSD – it was the start of modern individualism". The Conversation. July 6, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Drugs World". Informationisbeautiful.net. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Mark Deming. "Big Brother & the Holding Company: Sex, Dope & Cheap Thrills". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- S2CID 149680436.

- ^ "Beatles APPLE BOUTIQUE". Archived from the original on 2006-08-18. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- ISBN 0-495-50530-7, pp. 212–3.

- ^ ISBN 0-252-06915-3, pp. 59–60.

- ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1322–3.

- ^ a b c d St John, Graham. "Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival." Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture, 1(1) (2009).

- ^ Griffith, Martin. "Psychedelic Festival to Attract 24,000 Fans", The Albany Herald, September 1, 2001. Accessed on July 22, 2011 from Google News Archive.

- ISSN 1947-5403.

- PMID 21051213.

- ^ Aman, Jacob. (July 9, 2015) "Breaking Convention: A Multidisciplinary Conference on Psychedelic Consciousness", Breaking Convention 2015 Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ "Psychedelic Science", Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies: MAPS Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ "History of Entheogenesis Australis". Entheogenesis Australis (EGA).

External links

- Erowid

- Science & Consciousness Review, The Neurochemistry of Psychedelic Experience

- Psychedelic History

- Artists interpretation of psychedelic experiences.

- Online archive: Religion and Psychoactive Sacraments

- Magic Mushrooms and Reindeer - Weird Nature. A short video on the use of