Mescaline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

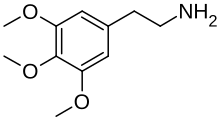

| Other names | 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenethylamine, TMPEA, Peyote |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | mescaline |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 6 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 35 to 36 °C (95 to 97 °F) |

| Boiling point | 180 °C (356 °F) at 12 mmHg |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Mescaline or mescalin (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a

Biological sources

It occurs naturally in several species of cacti. It is also reported to be found in small amounts in certain members of the bean family, Fabaceae, including Senegalia berlandieri (syn. Acacia berlandieri),[2] although these reports have been challenged and have been unsupported in any additional analyses.[3]

| Plant source | Amount of Mescaline (% of dry weight) |

|---|---|

| Echinopsis lageniformis (Bolivian torch cactus, syns. Echinopsis scopulicola, Trichocereus bridgesii)[4] | 0.25-0.56; 0.85 under its synonym Echinopsis scopulicola[5] |

| Leucostele terscheckii (syns Echinopsis terscheckii, Trichocereus terscheckii)[6] | 0.005 - 2.375[7][8] |

| Peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii)[9] | 0.01-5.5[10] |

| Trichocereus macrogonus var. macrogonus (Peruvian torch, syns Echinopsis peruviana, Trichocereus peruvianus)[11] | 0.01-0.05;[7] 0.24-0.81[5] |

| Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi (San Pedro cactus, syns Echinopsis pachanoi, Echinopsis santaensis, Trichocereus pachanoi)[12] | 0.23-4.7;[5] 0.32 under its synonym Echinopsis santaensis[5] |

| Trichocereus uyupampensis (syn. Echinopsis uyupampensis) | 0.05[5] |

As can be observed from the table above, the concentration of mescaline in different specimens can vary largely within a single species. Moreover, the concentration of mescaline within a single specimen varies as well. In columnar species like E. lageniformis, E. pachanoi and E. peruviana, the concentration of mescaline is highest at the top while in L. williamsii, mescaline appears to concentrate mainly at the sides of the cactus.[13]

History and use

In traditional peyote preparations, the top of the cactus is cut off, leaving the large tap root along with a ring of green photosynthesizing area to grow new heads. These heads are then dried to make disc-shaped buttons. Buttons are chewed to produce the effects or soaked in water to drink. However, the taste of the cactus is bitter, so contemporary users will often grind it into a powder and pour it into capsules to avoid having to taste it. The usual human dosage is 200–400 milligrams of mescaline sulfate or 178–356 milligrams of mescaline hydrochloride.[20][21] The average 76 mm (3.0 in) peyote button contains about 25 mg mescaline.[22]

Mescaline was first isolated and identified in 1897 by the German chemist Arthur Heffter[23] and first synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth.[24]

In 1955, English politician

Potential medical usage

Mescaline has a wide array of suggested medical usage, including treatment of alcoholism[26] and depression.[27] However, its status as a Schedule I controlled substance in the Convention on Psychotropic Substances limits availability of the drug to researchers. Because of this, very few studies concerning mescaline's activity and potential therapeutic effects in humans have been conducted since the early 1970s.[28][29][30]

Biosynthesis

Mescaline is biosynthesized from tyrosine which, in turn, is derived from phenylalanine by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. In Lophophora williamsii (Peyote), dopamine converts into mescaline in a biosynthetic pathway involving m-O-methylation and aromatic hydroxylation.[31]

Tyrosine and phenylalanine serve as metabolic precursors towards the synthesis of mescaline. Tyrosine can either undergo a decarboxylation via

Phenylalanine serves as a precursor by first being converted to L-tyrosine by L-amino acid hydroxylase. Once converted, it follows the same pathway as described above.[32][33]

Laboratory synthesis

Mescaline was first synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth from 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl chloride.[24] Subsequent to this, numerous approaches utilizing different starting materials have been developed. Notable examples include the following:

- Hofmann rearrangement of 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylpropionamide.[35]

- Henry reaction of 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde with nitromethane followed by nitro compound reduction of ω-nitrotrimethoxystyrene.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44]

- Ozonolysis of elemicin followed by reductive amination.[45]

- Ester reduction of Eudesmic acid's methyl ester followed by halogenation, Kolbe nitrile synthesis, and nitrile reduction.[46][47][48]

- Amide reduction of 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylacetamide.[49]

- Reduction of 3,4,5-trimethoxy(2-nitrovinyl)benzene with lithium aluminum hydride.[50]

- Treatment of tricarbonyl-(η6-1,2,3-trimethoxybenzene) chromium complex with acetonitrile carbanion in THF and iodine, followed by reduction of the nitrile with lithium aluminum hydride.[46]

Pharmacokinetics

About half the initial dosage is excreted after six hours, but some studies suggest that it is not metabolized at all before excretion. Mescaline appears not to be subject to metabolism by CYP2D6[52] and between 20% and 50% of mescaline is excreted in the urine unchanged, with the rest being excreted as the deaminated-oxidised-carboxylic acid form of mescaline, a likely result of MAO degradation.[53] The LD50 of mescaline has been measured in various animals: 212 mg/kg i.p. (mice), 132 mg/kg i.p. (rats), and 328 mg/kg i.p. (guinea pigs). For humans, the LD50 of mescaline has been reported to be approximately 880 mg/kg.[54]

Behavioral and non-behavioral effects

Mescaline induces a psychedelic state comparable to those produced by LSD and psilocybin, but with unique characteristics.[30] Subjective effects may include altered thinking processes, an altered sense of time and self-awareness, and closed- and open-eye visual phenomena.[50]

Prominence of color is distinctive, appearing brilliant and intense. Recurring visual patterns observed during the mescaline experience include stripes, checkerboards, angular spikes, multicolor dots, and very simple

Heinrich Klüver coined the term "cobweb figure" in the 1920s to describe one of the four form constant geometric visual hallucinations experienced in the early stage of a mescaline trip: "Colored threads running together in a revolving center, the whole similar to a cobweb". The other three are the chessboard design, tunnel, and spiral. Klüver wrote that "many 'atypical' visions are upon close inspection nothing but variations of these form-constants."[56]

As with LSD, synesthesia can occur especially with the help of music.[57] An unusual but unique characteristic of mescaline use is the "geometrization" of three-dimensional objects. The object can appear flattened and distorted, similar to the presentation of a Cubist painting.[58]

Mescaline elicits a pattern of sympathetic arousal, with the peripheral nervous system being a major target for this substance.[57]

According to a research project in the Netherlands, ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.[59]

Mechanism of action

In plants, mescaline may be the end-product of a pathway utilizing catecholamines as a method of stress response, similar to how animals may release such compounds and others such as cortisol when stressed. The in vivo function of catecholamines in plants has not been investigated, but they may function as antioxidants, as developmental signals, and as integral cell wall components that resist degradation from pathogens. The deactivation of catecholamines via methylation produces alkaloids such as mescaline.[32]

In humans, mescaline acts similarly to other psychedelic agents.

| Binding sites | Binding affinity Ki (μM)[65] |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 4.6 |

| 5-HT2A | 6.3 |

| 5-HT2C | 17 |

| α1A | >15 |

| α2A | 1.4 |

| TAAR1 | 3.3 |

Difluoromescaline and trifluoromescaline are more potent than mescaline, as is its amphetamine homologue trimethoxyamphetamine.[66][67] Escaline and proscaline are also both more potent than mescaline, showing the importance of the 4-position substituent with regard to receptor binding.[68]

Legality

United States

In the United States, mescaline was made illegal in 1970 by the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act, categorized as a Schedule I hallucinogen.[69] The drug is prohibited internationally by the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[70] Mescaline is legal only for certain religious groups (such as the Native American Church by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978) and in scientific and medical research. In 1990, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Oregon could ban the use of mescaline in Native American religious ceremonies. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) in 1993 allowed the use of peyote in religious ceremony, but in 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that the RFRA is unconstitutional when applied against states.[citation needed] Many states, including the state of Utah, have legalized peyote usage with "sincere religious intent", or within a religious organization,[citation needed] regardless of race.[71] Synthetic mescaline, but not mescaline derived from cacti, was officially decriminalized in the state of Colorado by ballot measure Proposition 122 in November 2022.[72]

While mescaline-containing cacti of the genus Echinopsis are technically controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act, they are commonly sold publicly as ornamental plants.[73]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, mescaline in purified powder form is a Class A drug. However, dried cactus can be bought and sold legally.[74]

Australia

Mescaline is considered a schedule 9 substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (February 2020).[75] A schedule 9 substance is classified as "Substances with a high potential for causing harm at low exposure and which require special precautions during manufacture, handling or use. These poisons should be available only to specialised or authorised users who have the skills necessary to handle them safely. Special regulations restricting their availability, possession, storage or use may apply."[75]

Other countries

In Canada, France, The Netherlands and Germany, mescaline in raw form and dried mescaline-containing cacti are considered illegal drugs. However, anyone may grow and use peyote, or Lophophora williamsii, as well as Echinopsis pachanoi and Echinopsis peruviana without restriction, as it is specifically exempt from legislation.[9] In Canada, mescaline is classified as a schedule III drug under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, whereas peyote is exempt.[76]

In Russia mescaline, its derivatives and mescaline-containing plants are banned as narcotic drugs (Schedule I).[77]

Notable users

- Antonin Artaud wrote 1947's The Peyote Dance, where he describes his peyote experiences in Mexico a decade earlier.[78]

- since they were easier on the stomach.

- Allen Ginsberg took peyote. Part II of his poem "Howl" was inspired by a peyote vision that he had in San Francisco.[79]

- Ken Kesey took peyote prior to writing One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

- Jean-Paul Sartre took mescaline shortly before the publication of his first book, L'Imaginaire; he had a bad trip during which he imagined that he was menaced by sea creatures. For many years following this, he persistently thought that he was being followed by lobsters, and became a patient of Jacques Lacan in hopes of being rid of them. Lobsters and crabs figure in his novel Nausea.

- Havelock Ellis was the author of one of the first written reports to the public about an experience with mescaline (1898).[80][81][82]

- Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Polish writer, artist and philosopher, experimented with mescaline and described his experience in a 1932 book Nikotyna Alkohol Kokaina Peyotl Morfina Eter.[83]

- Aldous Huxley described his experience with mescaline in the essay "The Doors of Perception" (1954).

- Jim Carroll in The Basketball Diaries described using peyote that a friend smuggled from Mexico.

- Hunter S. Thompson wrote an extremely detailed account of his first use of mescaline in "First Visit with Mescalito", and it appeared in his book Songs of the Doomed, as well as featuring heavily in his novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

- Psychedelic research pioneer Alexander Shulgin said he was first inspired to explore psychedelic compounds by a mescaline experience.[84] In 1974, Shulgin synthesized 2C-B, a psychedelic phenylethylamine derivative, structurally similar to mescaline,[85] and one of Shulgin's self-rated most important phenethylamine compounds together with Mescaline, 2C-E, 2C-T-7, and 2C-T-2.[86]

- Bryan Wynter produced Mars Ascends after trying the substance for the first time.[87]

- George Carlin mentioned mescaline use during his youth while being interviewed in 2008.[88]

- Carlos Santana told about his mescaline use in a 1989 Rolling Stone interview.[89]

- Disney animator Ward Kimball described participating in a study of mescaline and peyote conducted by UCLA in the 1960s.[90]

- Michael Cera used real mescaline for the movie Crystal Fairy & the Magical Cactus, as expressed in an interview.[91]

- Philip K. Dick was inspired to write Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said after taking mescaline.[92]

- Arthur Kleps, a psychologist turned drug legalization advocate and writer whose Neo-American Church defended use of marijuana and hallucinogens such as LSD and peyote for spiritual enlightenment and exploration, bought, in 1960, by mail from Delta Chemical Company in New York 1 g of mescaline sulfate and took 500 mg. He experienced a psychedelic trip that caused profound changes in his life and outlook.

See also

- List of psychedelic plants

- Methallylescaline

- Psychedelic experience

- Psychoactive drug

- Entheogen

- The Doors of Perception

- Mind at Large (concept in The Doors of Perception)

- The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead

References

- ^ Anvisa (24 July 2023). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 25 July 2023). Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Forbes TD, Clement BA. "Chemistry of Acacia's from South Texas" (PDF). Texas A&M Agricultural Research & Extension Center at Uvalde. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011.

- ^ "Acacia species with data conflicts". sacredcacti.com. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Bury B (2 August 2021). "Could Synthetic Mescaline Protect Declining Peyote Populations?". Chacruna. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ PMID 20637277.

- ^ "Cardon Grande (Echinopsis terscheckii)". Desert-tropicals.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Partial List of Alkaloids in Trichocereus Cacti". Thennok.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Forbidden Fruit Archives Archived 2005-11-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9635626-9-2.

- S2CID 32474292.

- PMID 20637277.

- PMID 4773270. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- .

- ^ PMID 15990261.

- ISBN 978-0806120317.

- S2CID 252954052.

- PMID 17090303.

- PMID 24565054.

- S2CID 135116632.

- ^ "#96 M – Mescaline (3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenethylamine)". PIHKAL. Erowid.org. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- PMID 33949246.

- ISBN 978-0-87488-182-0.

- ^ "Arthur Heffter". Character Vaults. Erowid.org. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ S2CID 104408477.

- ^ "Panorama: The Mescaline Experiment". February 2005. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Could LSD treat alcoholism?". abcnews.go.com. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Magic Mushrooms could treat depression". news.discovery.com. 23 January 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Carpenter DE (8 July 2021). "Mescaline is Resurgent (Yet Again) As a Potential Medicine". Lucid News. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- PMID 33860184.

- ^ S2CID 252548055.

- ISBN 978-0-471-49641-0.

- ^ .

- PMID 779022.

- ^ "Mescaline : D M Turner". www.mescaline.com.

- .

- ^ Amos D (1964). "Preparation of Mescaline from Eucalypt Lignin". Australian Journal of Pharmacy. 49: 529.

- S2CID 93188741.

- .

- ISBN 9780963009609.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- ^ .

- S2CID 97553172.

- ISBN 978-0123705518.

- .

- ^ PMID 20716904.

- ^ Smith MV. "Psychedelics and Society". Erowid.org. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- PMID 9264312.

- PMID 14814616.

- ^ Buckingham J (2014). "Mescaline". Dictionary of Natural Products: 254–260.

- ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

- ^ A Dictionary of Hallucations. Oradell, NJ.: Springer. 2010. p. 102.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-02-328764-0.

- ISBN 978-0-87489-499-8.

- ISSN 1050-8619.

- PMID 14761703.

- PMID 2707301.

- PMID 9301661.

- PMID 17535909.

- ^ "Neuropharmacology of Hallucinogens". Erowid.org. 27 March 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- S2CID 6685927.

- PMID 22374819. Archived from the originalon 3 June 2013.

- ^ Shulgin A. "#157 TMA - 3,4,5-TRIMETHOXYAMPHETAMINE". PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Erowid.org. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- S2CID 30796368.

- ^ United States Department of Justice. "Drug Scheduling". Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ^ "State v. Mooney". utcourts.gov. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Colorado Proposition 122, Decriminalization and Regulated Access Program for Certain Psychedelic Plants and Fungi Initiative (2022)".

- ISBN 9780123704672.

- ^ "2007 U.K. Trichocereus Cacti Legal Case Regina v. Saul Sette". Erowid.org. June 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Poisons Standard February 2020. comlaw.gov.au

- ^ "Justice Laws Search". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Постановление Правительства РФ от 30.06.1998 N 681 "Об утверждении перечня наркотических средств, психотропных веществ и их прекурсоров, подлежащих контролю в Российской Федерации" (с изменениями и дополнениями) - ГАРАНТ". base.garant.ru.

- ^ Doyle P (20 May 2019). "Patti Smith Channels French Poet Antonin Artaud on Peyote". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "The Father of Flower Power". The New Yorker. 10 August 1968. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Ellis H (1898). "Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise". The Contemporary Review. Vol. LXXIII.

- ISBN 978-0-7141-1736-2.

- ISBN 978-1-57066-053-5.

- ^ Witkiewicz SI, Biczysko S (1932). Nikotyna, alkohol, kokaina, peyotl, morfina, eter+ appendix. Warsaw: Drukarnia Towarzystwa Polskiej Macierzy Szkolnej.

- ^ "Alexander Shulgin: why I discover psychedelic substances". Luc Sala interview. Mexico. 1996. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- PMID 29593537.

- ^ "Mescaline". Psychedelic Science Review. 2 December 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Bird M (2012). 100 Ideas that Changed Art. London: Laurence King Publishing.

- ^ Dixit J (23 June 2008). "George Carlin's Last Interview". Psychology Today.

- ^ Greene A (1989). "Dazed and Confused: 10 Classic Drugged-Out Shows". Rolling Stone.

Santana at Woodstock, 1969 - Mescaline

- ^ "Ward Kimball's Final Farewell". cartoonician.com. 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Boardman M (10 July 2013). "Michael Cera Took Drugs On-Camera". Huffington Post.

- ^ "FLOW MY TEARS". www.philipkdickfans.com. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

Further reading

- Jay M (2019). Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic. Yale University Press.

- Klüver H (1942). "Mechanisms of hallucinations." (PDF). In McNemar Q, Merrill MA (eds.). Studies in personality. McGraw-Hill. pp. 175–207.

- ISBN 9780593296905.

External links

- National Institutes of Health – National Institute on Drug Abuse Hallucinogen InfoFacts

- Mescaline at Erowid

- Mescaline at PsychonautWiki

- PiHKAL entry

- Mescaline entry in PiHKAL • info

- Film of Christopher Mayhew's mescaline experiment on YouTube

- Mescaline: The Chemistry and Pharmacology of its Analogs, an essay by Alexander Shulgin

- Mescaline on the Mexican Border