Psychic archaeology

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

Psychic archaeology is a loose collection of practices involving the application of paranormal phenomena to problems in archaeology. It is not considered part of mainstream archaeology, or taught in academic institutions. It is difficult to test scientifically, since archaeological sites are relatively abundant, and all of its verified predictions could have been made via educated guesses.[1][2]

Practitioners of psychic archaeology utilize a variety of methods of divination ranging from pseudoscientific methods such as dowsing and channeling.[3] Some psychic archaeologists engage in fieldwork while others, such as Edgar Cayce (who claims to have had access to ancient Akashic records), exclusively engage in remote viewing. Frederick Bligh Bond's research at Glastonbury Abbey is one of the first documented examples of psychic archaeology and remains a principal case in many discussions of psychic archaeology.[4]

Description

Psychic archaeology is the use of

Methods

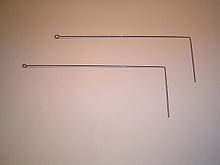

There are several common methods employed by practitioners of psychic archaeologists including:

Dowsing

Psychometry

An example of

Others

Sites

Chichén Itzá

Glastonbury Abbey

F. Bligh Bond began excavation at Glastonbury in the summer of 1909. While excavating he demonstrated the accuracy of Captain Bartlett's sketches discovering Edgar Chapel in the location indicated by Captain Bartlett.[7]

Bond didn't reveal that he was using psychic powers until 1917, when he had already presented his results. The Church of England officials were so embarrassed that they fired him.[12]

Mainstream archeologists are far from nonplussed about the discovery, reminding people that F. Bligh Bond was an expert in medieval church architecture, that most of the site had already been dug out, and that the location of the chapel could be easily guessed from the existing data.

Point Cook

Others

Validity

Advocates of

It is difficult to test psychic archaeology empirically, since archaeological discoveries are relatively abundant; anyone can predict the location of a site, using only a bit of archaeological knowledge and common sense.[1] The same applies for finding objects inside an already identified site.[1] Also, some sites, like the Alexandria harbor, are so rich in objects that one can dig in any random place and find at least one object.[1] Predictions about the lifestyle of ancient civilizations can't be verified due to the lack of written records.[1]

Names in psychic archaeology

- Hella Hammid[17]

- Augustus Le Plongeon

- Frederick Bligh Bond[15]

- George S. McMullen[18]

- Stefan Ossowiecki[7]

- Edgar Cayce[4]

- Karen Hunt Bent Spoon Award)

- J. Norman Emerson [4] of the University of Toronto

- Stephan A. Schwartz[15]

- Jeffrey Goodman[7]

In fiction

- pole shifttheory.

See also

- New Age

- Pseudoarchaeology

- Ancient astronauts

- Mayanism

- Atlantis

- Psychic detective

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Psychic

- Alfred Schuler

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-37918-5

- ^ Cole, John R. (1978). "Anthropology Beyond the Fringe: Ancient Inscriptions, Early Man and Scientific Method". The Skeptical Inquirer 2(2): 62–71.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth L. (1980). "Psychic Archaeology: The Anatomy of Irrationalist Prehistoric Studies". The Skeptical Inquirer 4(4): 32–43.

- ^ ISBN 0-8122-1312-2.

- ^ a b c Plummer, Mark (1991). "Locating Invisible Buildings". The Skeptical Inquirer. 15 (4): 386–397.

- ^ Van Leusen, Martijn (1999). "Dowsing and Archaeology". The Skeptical Inquirer. 23 (2): 33–41.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-425-05000-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-292-72221-7., p. 131

- ^ Desmond, Lawrence; Phyllis, Messenger (1988). A Dream of Maya: Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon in Nineteenth-Century Yucatan. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press., p. 131

- ^ Desmond, Lawrence; Phyllis, Messenger (1988). A Dream of Maya: Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon in Nineteenth-Century Yucatan. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ "History and Archaeology – Glastonbury Abbey". Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8131-2467-4

- ISBN 978-0767427227.

- ^ a b Varvoglis, Mario. "Psychic Archeology". Parapsychological Association. Archived from the original on 2004-06-18. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ ISBN 0-448-12717-2.

- ^ Doeser, James (2008). "Psychic Archaeology". Bad Archaeology. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ CIA.gov [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Psychic Archeology by Mario Varvoglis Ph.D.

Further reading

- Bailey, Richard, Eric Cambridge and Dennis Biggs. 1988. Dowsing and Church Archaeology. ISBN 978-0-946707-13-3

- Bond, Fredrick. 2010 (Reprint). The Gates of Remembrance. ISBN 978-0-548-00420-3

- Jones, David. 1979. Visions of Time: Experiments In Psychic Archaeology ISBN 0-8356-0525-6

- McKusick, Marshall (1982), "Psychic Archaeology: Theory, Method, and Mythology", Journal of Field Archaeology, 9 (1): 99–118(20),

- Schwartz, Stephan. 1983. The Alexandria Project. ISBN 978-0-595-18348-7