Treaty of Riga

| |

| Signed | 18 March 1921 |

|---|---|

| Location | Riga, Latvia |

| Ratified | |

| Expiration | 17 September 1939 |

| Parties |

|

| Ratifiers | Sejm Russian Soviet Ukrainian Soviet |

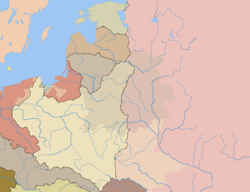

| Territorial evolution of Poland in the 20th century |

|---|

The Treaty of Riga was signed in

Under the treaty, Poland recognized Soviet Ukraine and Belarus, abrogating its 1920 Treaty of Warsaw with the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Treaty of Riga established a Polish–Soviet border about 250 kilometres (160 mi) east of the Curzon Line, incorporating large numbers of Ukrainians and Belarusians into the Second Polish Republic. Poland, which agreed to withdraw from areas further east (notably Minsk), renounced claims to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth's border prior to the 1772 First Partition of Poland, recovering only those eastern regions (Kresy) lost to Russia in the 1795 Third Partition. Russia and Ukraine agreed to withdraw their claims to lands west of the demarcated border line. Poland, by recognising the puppet states of the USSR and simultaneously withdrawing recognition of the UPR (its only ally in the Polish-Bolshevik war), was in fact giving up on the federation programme, while Russia approved of the fact that the whole of Galicia, as well as the territories of the former Russian Empire, inhabited largely by non-Polish people, were to be found within Poland's borders. The treaty also addressed matters of sovereignty, citizenship, national minorities, repatriation, and diplomatic and commercial relations. The Treaty lasted until the invasion of Poland by the Soviet Union in 1939, and their borders were redefined by an agreement in 1945.

Background

The

Negotiations

Peace talks began in Minsk on 17 August 1920, but the talks were moved to Riga, and resumed on 21 September.[5] The Soviets proposed two solutions, the first on 21 September and the second on 28 September. The Polish delegation made a counter-offer on 2 October. Three days later the Soviets offered amendments to the Polish offer, which Poland accepted. An armistice was signed on 12 October and went into effect on 18 October 1920.[6] The chief negotiators were Jan Dąbski for Poland[3] and Adolph Joffe for the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[5] The Soviet side insisted, successfully, on excluding non-communist Ukrainian representatives from the negotiations.[5]

The Soviets' military setbacks made their delegation offer Poland substantial territorial concessions in the contested border areas. However, to many observers, it looked as though the Polish side conducted the Riga talks as if Poland had lost the war. The Polish delegation was dominated by members of the

That decision was also motivated by political objectives. The National Democrats' base of public support was among Poles in central and western Poland. In the east of the country and in the disputed borderlands, support for the National Democrats was greatly outweighed by support for Piłsudski, and in the countryside, outside the cities, Poles were outnumbered by Ukrainians or Belarusians in those areas. A border too far to the east would thus be against not only the National Democrats' ideological objective of minimising the minority population of Poland but also their electoral prospects.[7] Warweary public opinion in Poland also favoured an end to the negotiations,[5] and both sides remained under pressure from the League of Nations to reach a deal.

A special parliamentary delegation, consisting of six members of the Polish Sejm, held a vote on whether to accept the Soviets' far-reaching concessions, which would have left Minsk on the Polish side of the border. Pressured by the National Democrat ideologue, Stanisław Grabski, the 100 km of extra territory was rejected, a victory for the nationalist doctrine and a stark defeat for Piłsudski's federalism.[5][3]

Regardless, the peace negotiations dragged on for months because of Soviet reluctance to sign. However, the matter became more urgent for the Soviet leadership, which had to deal with increased internal unrest towards the end of 1920, such as the Tambov Rebellion and later the Kronstadt rebellion against the Soviet authorities. As a result, Vladimir Lenin ordered the Soviet plenipotentiaries to finalise the peace treaty with Poland.[4]

The Treaty of Riga, signed on 18 March 1921, partitioned the disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and Russia and ended the conflict.

Terms

The Treaty consisted of 26 articles.[8] Poland was to receive monetary compensation (30 million rubles in gold) for its economic input into the Russian Empire during the Partitions of Poland. Under Article 14 Poland was also to receive railway materials (locomotives, rolling stock, etc.) with a value of 29 million gold roubles.[9] Russia was to surrender works of art and other Polish national treasures acquired from Polish territories after 1772 (such as the Jagiellonian tapestries and the Załuski Library). Both sides renounced claims to war compensation. Article 3 stipulated that border issues between Poland and Lithuania would be settled by those states.[8]

TREATY OF PEACE BETWEEN POLAND, RUSSIA AND THE UKRAINE Riga, March 18, 1921 Article 3. Russia and the Ukraine abandon all rights and claims to the territories situated to the west of the frontier laid down by Article 2 of the present Treaty. Poland, on the other hand, abandons in favour of the Ukraine and of White Ruthenia all rights and claims to the territory situated to the east of this frontier. Article 4. Each of the Contracting Parties mutually undertakes to respect in every way the political sovereignty of the other Party, to abstain from interference in its internal affairs, and particularly to refrain from all agitation, propaganda or interference of any kind, and not to encourage any such movement.[10]

Article 6 created citizenship options for persons on either side of the new border.[8] Article 7 consisted of a mutual guarantee that all nationalities would be permitted "free intellectual development, the use of their national language, and the exercise of their religion."[8] In the treaty, it was agreed that Poland would refuse to form federations with Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.[11]

Aftermath

The Allied Powers were initially reluctant to recognise the treaty, which had been concluded without their participation.[8] Their postwar conferences had supported the Curzon Line as the Polish-Russian border, and Poland's territorial gains in the treaty lay about 250 km east of that line.[12][13] French support led to its recognition in March 1923 by France, the United Kingdom, Italy and Japan, followed by the United States in April.[8]

In Poland, the Treaty of Riga was met with criticism from the very beginning. Some characterised the treaty as short-sighted and argued that much of what Poland had gained during the Polish-Soviet war was lost during the peace negotiations. Józef Piłsudski had participated in the Riga negotiations only as an observer and called the resulting treaty "an act of cowardice".[14] Piłsudski felt the agreement was a shameless and short-sighted political calculation, with Poland abandoning its Ukrainian allies.[5] On 15 May 1921, he apologised to Ukrainian soldiers during his visit to the internment camp at Kalisz.[15][16][17] The treaty substantially contributed to the failure of his plan to create a Polish-led Intermarium federation of Eastern Europe, as portions of the territory that had been proposed for the federation were ceded to the Soviets.[7]

Lenin also considered the treaty unsatisfactory, as it forced him to put aside his plans for exporting the Soviet revolution to the West.[4]

The Belarusian and Ukrainian independence movements saw the treaty as a setback.

According to the Belarusian historian Andrew Savchenko, Poland's new eastern border was "military indefensible and economically unviable" and a source of growing ethnic tensions, as the resulting minorities in Poland were too large to be ignored or assimilated and too small to win their desired autonomy.[3]

Further consequences

While the Treaty of Riga led to a two-decade stabilisation of Soviet-Polish relations, conflict was renewed with the

In the view of some foreign observers, the treaty's incorporation of significant minority populations into Poland led to seemingly insurmountable challenges, because the newly formed organizations such as

The populations separated from Poland by the new Polish-Soviet border experienced a different fate from their fellow citizens. Ethnic Poles left within Soviet borders were subjected to discrimination and property confiscation.

Belarusians and Ukrainians, having failed to create their own states, were subjects of repression in the Soviet Union, and even liquidation e.g.

The Soviet Union, although thwarted in 1921, would see its sphere of influence expand as a result of

However, in 1989, Poland would regain its full sovereignty, and soon afterwards, with the

would go on to become independent nations.See also

- Poles in the Soviet Union

- Belarusians in Poland

- Ukrainians in Poland

- Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Aftermath of the Polish-Soviet War

- Polish Operation of the NKVD

- Latvian–Soviet Peace Treaty

- Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty

- Treaty of Tartu (Estonia–Russia)

- Treaty of Tartu (Finland–Russia)

- Ukrainians in Toruń

- Russians in Toruń

Notes

- ^ a b Text of the document. Германо-советско-польская война 1939 года website.

- ^ K. Marek. Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law. Librairie Droz 1968. pp. 419–420.

- ^ ISBN 978-9004174481.

- ^ a b c d The Rebirth of Poland. University of Kansas, lecture notes by Professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- ^ )

- ^ Soviet foreign policy: 1917–1980, in two volumes, Volume 1. Progress Publishers. p. 181.

- ^ ISBN 978-0300105865. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-895571-05-9.

- ISBN 978-81-7488-491-6.

- ^ Partial English text of the Treaty of Riga as Appendix C in G.V. Kacewicz (2012), Great Britain, The Soviet Union and the Polish Government in Exile (1939–1945), p. 229–230. The full text has 26 articles. "Treaty of Peace Between Poland, Russia and the Ukraine" (PDF). Riga, March 18, 1921. Resource: Appendix C.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Butkus, Zenonas; Aleknavičė, Karolina. "Stebuklas prie Vyslos: kaip 1920 metais lenkai sutriuškino bolševikus". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-12116-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8264-7301-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7126-0694-3. (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.)

- ISSN 0209-1747. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-300-12121-6.

- ^ Polityka. Wydawn. Wspólczesne RSW "Prasa-Książka-Ruch". 2001. p. 74.

Ja was przepraszam, panowie, ja was przepraszam – to miało być zupełnie inaczej

- ISBN 978-0-8133-1794-6.

- ISBN 978-0-312-23556-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4067-4564-1.

- ISBN 978-0415106917– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0415343589.

- ^ J. M. Kupczak "Stosunek władz bolszewickich do polskiej ludności na Ukrainie (1921–1939)Wrocławskie Studia Wschodnie 1 (1997) Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, 1997, page 47–62" IPN Bulletin 11(34) 2003

- ^ Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (15 January 2011). "Nieopłakane ludobójstwo (Genocide Not Mourned)". Rzeczpospolita. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-521-19196-8. p. 217.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (27 January 2011). "Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Was Worse?". The New York Review of Books. p. 1, paragraph #7. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ISBN 9780415486187.

- ISBN 978-1-60494-325-2. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-415-17893-8. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

Further reading

- Dąbrowski, Stanisław. "The Peace Treaty of Riga." The Polish Review (1960) 5#1: 3–34. Online

- ISBN 0712606947. (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.)

- Materski, Wojciech. "The Second Polish Republic in Soviet Foreign Policy (1918–1939)." Polish Review 45.3 (2000): 331–345. online

- Traktat ryski 1921 roku po 75 latach, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, Toruń 1998, ISBN 8323109745(Chapter summaries in English)

- Photocopies of the Polish version of the Treaty. Dziedzictwo.polska.pl