1939 New York World's Fair pavilions and attractions

The

The New York World's Fair Corporation (WFC) oversaw the 1939 fair and leased out the land to exhibitors. The WFC built about 100 buildings, which were developed in a classical style, while the remaining buildings were constructed in a variety of styles. Most of the world's major nations had exhibits, and the fairground also hosted exhibits from states, corporations, and various groups. After the fair, some pavilions were preserved or relocated, but the vast majority of structures were demolished.

Background

Fair

In September 1935, the New York City Board of Estimate voted to allow Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, then an ash dump, to be used as the site of the 1939 New York World's Fair.[1] The New York World's Fair Corporation (WFC) was formed to oversee the exposition in October 1935,[2] and the WFC took over the site in 1936.[3] The WFC announced details of the fair's master plan in October 1936, which called for an exposition themed to "the world of tomorrow".[4] The World's Fair officially opened on April 30, 1939,[5] and its first season ended on October 31, 1939.[6] The fair reopened for a second and final season on May 11, 1940,[7] closing on October 27, 1940.[8] Demolition of the buildings began immediately after the fair ended,[9][10] but seven structures were preserved as part of the park.[11]

There were 1,500 exhibitors on the fair's opening day, representing about 40 industries.[12] In addition, 62 nations and 35 U.S. states or territories (including the U.S. federal government) leased space at the fair.[13] The fairground was divided into seven geographic or thematic zones, five of which had "focal exhibits", as well as two focal exhibits housed in their own buildings.[14] The plan called for numerous wide tree-lined pathways, including a central "Cascade Mall" leading to the Trylon and Perisphere.[15][16] The zones around the Trylon and Perisphere were all color-coded.[17][18] Despite the fair's futuristic theme, the fairground's layout—with streets radiating from the theme center—was heavily inspired by classical architecture.[16] Some streets in the fairground were named after notable Manhattan thoroughfares or American historical figures, while others were named based on their function.[19]

Pavilions

The fair had about 375 buildings, of which 100 were developed by the WFC.[20] Many of the buildings were designed in "symbolically representative and stylistically individualistic" styles.[16] The pavilions relied almost entirely on artificial light,[21][22] and their steel frames were bolted together so they could be easily disassembled after the fair.[17] The smallest standalone exhibition building was the House of Jewels, which covered 9,928 square feet (922.3 m2), while the largest was the General Motors pavilion, which covered 299,439 square feet (27,818.8 m2).[23]

The buildings included design features such as domes, spirals, buttresses, porticos, rotundas, tall pylons, and corkscrew-shaped ramps.[21][24] The buildings developed by the WFC tended to follow specific design guidelines.[20] In particular, these buildings were generally one story high and made of steel, gypsum, and stucco, while the interiors were split into spaces of uniform dimensions.[25] In contrast to the WFC's buildings, which had a classical architectural style, many of the individual exhibitors built more modernistic structures with curving facades.[26] Many of the buildings' facades were decorated with art, commissioned by both the WFC and by individual exhibitors;[27][28][29] the artwork included large murals, sculptures, and reliefs.[30] The structures were painted in about 100 hues, and some of the paint colors were developed specifically for the fair.[29] Ernest Peixotto oversaw the development of the murals and the fair's color-coding system.[31]

Communications and Business Systems Zone

Fairgoers walking to the north of the Theme Center on the Avenue of Patriots would encounter the Communications and Business Systems exhibits. The focal point of this area was the Communications Building, a large structure designed by Francis Keally and Leonard Dean, with a pair of 160-foot-high (49 m) pylons flanking it[32][33] and a mural by Eugene Savage.[27] Numerous smaller exhibitors had space in the Communications Building.[34] The structure also had a theater, a Stuart Davis mural about technology, and seven illuminated panels about communications technologies.[32] The building was renamed the Maritime, Transport and Communications Building in 1940.[35]

The Communications and Business Systems Zone also contained the following buildings:

| Pavilion | Architects | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Telephone & Telegraph | Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith[36]

|

A structure with several sections of varying heights.[37] The semicircular entrance court had a sculptural group called The Pony Express. Inside were several telecommunications exhibits, including one exhibit about the Voder electronic-voice synthesizer.[36] | [37][36] |

| Business Systems and Insurance Building | Eric Gugler, John B. Slee, and Robert H. Bryson[36] | An L-shaped structure that housed numerous companies such as Aetna, MetLife, and IBM.[38][39] The sculptor Joseph Kiselewski created a large sundial for the building.[40] | [38][39] |

| Crosley Corporation | Holland & White (architects); Sundberg-Ferar (designers)[41] | A building displaying the products of the | [41][42][43] |

| Masterpieces of Art | Harrison & Fouilhoux[41] | Three pavilions around a courtyard, which contained 25 galleries with valuable Old Master works, many of which were borrowed from Europe.[41] Different works of art were displayed during the 1939 and 1940 seasons.[44] | [41][44] |

| Radio Corporation of America | Skidmore & Owings[45] | A structure shaped like a radio tube. Inside were exhibits about televisions, broadcasting, and various types of radio communications; these included dioramas and a yacht.[45] There were also a lagoon and a park next to the structure.[46] | [45][46] |

Community Interest Zone

The Community Interest Zone was located just east of the Communications & Business Systems Zone.[47] The region's exhibits showcased several trades or industries that were popular among the public at the time, such as home furnishings, plumbing, contemporary art, cosmetics, gardens, the gas industry, fashion, jewelry, and religion.[48] The focal exhibit was the Home Furnishings Building, designed by Dwight James Baum; there were several displays from major companies, five smaller displays about home furnishings, and a mural by J. Scott Williams.[49] Besides the focal exhibit, the Community Interest Zone included the following buildings:

| Pavilion | Architects | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corporation | Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith[50]

|

A yellow-and-orange structure with a curved colonnade. Inside the colonnade were displays of heating appliances, air conditioners, and plumbing. | [50] |

| Christian Science | W. Pope Barney[51] | A visitor center for the Christian Science movement, with murals, conversation rooms, telephone booths, and reading rooms.[51] The building consisted of a rotunda topped by a circular tower.[52] | [51][52] |

| Contemporary Arts Building / American Arts Today | John V. Van Pelt[51]

|

A building with 23 exhibition galleries that displayed contemporary art, in addition to two studios where artists demonstrated how they created their work.[51] The building was renamed in 1940.[35] | [51] |

| Electrified Farm | Harrison & Fouilhoux[53] | A fully functioning farm with electrically powered appliances.[53] The farm included a farmhouse, orchard, barns, and crop fields.[54] | [53][54] |

| Gas Exhibits Inc. | Skidmore & Owings and John Moss[55] | A structure with an exhibit hall for 22 manufacturers and an auditorium.[55] There was also a "court of flame" and a model house with gas appliances.[56] | [55][56] |

| House of Jewels | J. Gordon Carr (architect); Raymond Loewy (designer)[57] | A simple concrete structure with jewelry displays, alongside an amphitheater with diamond exhibits.[58] At the time of its opening, the pavilion was described as the largest display of jewels and diamonds in the U.S.[59] | [58][59] |

| Johns-Manville Sales Corporation | Shreve, Lamb & Harmon[57] | A structure with exhibits about Johns Manville's industrial products and home-construction materials.[60] On the facade was the Asbestos Man sculpture designed by Hildreth Meière.[61] | [60][61] |

| Maison Coty | Cross & Cross and John Hironimus (architects); Donald Deskey (designer)[62] | A glass building with displays of Coty perfumes, as well as exhibits on the history and manufacturing process of perfumes. | [62] |

| Palestine Exhibits Inc.[a] | Arieh El-Hanani and Norvin R. Lindheim (architects); Lee Simonson (designer)[62] | A structure with displays about the history of the Jews in the Palestine region.[62] The building featured a monumental hammered copper relief sculpture on its facade titled The Scholar, The Laborer, and the Tiller of the Soil by Maurice Ascalon.[64] Several major Israeli artists presented their work, including Isaac Frenkel Frenel and Shimshon Holzman.[65]

|

[62] |

| Temple of Religion | Poor, Stein & Reagan[62] | A nonsectarian structure with a 150-foot-tall (46 m) circular tower. John W. Hausermann funded the new Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ that was installed in the building.[68]

|

[66][67] |

| Town of Tomorrow | — | A set of 15 "demonstration homes".[69] Each home was decorated by a different company; most of the houses were designed in an 18th-century style, though some were designed in a modern style.[70] | [69][70] |

| Works Progress Administration | Delano & Aldrich[71] | An exhibit with models of Works Progress Administration workers doing various tasks. There was also a 299-seat auditorium and an open courtyard where performances were held. | [72] |

| Young Men's Christian Association of the City of New York | Dwight James Baum[71] | A visitor center for the YMCA, with a restaurant, meeting areas, and lounges.[73] There was also a large map of YMCA locations worldwide.[71] | [73][71] |

Government Zone

The Government Zone was located at the east end of the fair, on the eastern bank of the Flushing River. It contained a centrally located Court of Peace, a Lagoon of Nations, and a smaller Court of States.[74][75] The Hall of Nations consisted of eight buildings,[75] which flanked the Court of Peace.[76] The 60 foreign governments built many pavilions housing a myriad of cultural offerings.[74][77] Nations could build their own pavilions or lease space in the Hall of Nations; some nations chose to do both.[78] Nazi Germany was the only major country that did not have any exhibits at the fair,[79][23] though this was more because of the Germans' lack of money than opposition to the Nazi regime.[80] China initially did not have a pavilion at the fair due to the ongoing Sino-Japanese War,[23] but a Chinese exhibit was added during the 1940 season.[81] The U.S. government also developed a pavilion for smaller South American and European governments that could not afford their own pavilions.[82] The Soviet pavilion, demolished after the 1939 season, was replaced with the American Common in 1940.[83]

Standalone pavilions

The following nations had standalone pavilions.[84]

| Pavilion | Architects | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | — | A structure surrounded by four pylons with glass showcases, including a diorama. There was a fine arts room, exhibition hall, theater, restaurant, and other visitor spaces.[85] The pavilion displayed work from Argentine artists and movies about life in Argentina.[86] This pavilion only operated during the 1939 season.[87][88] | [85][86] |

| Belgium | Van de Velde Stynen and Bourgeois[89] | A structure constructed of Belgian materials, including a 155-foot (47 m) bell tower made of Belgian slate. Inside were a reception hall, restaurant, offices, movie theater, and three exhibition spaces.[89] A collection of Belgian diamonds was also displayed.[90] | [89][90] |

| Brazil | Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer[89] | A two-story, L-shaped building with plants, a Good Neighbor hall, and exhibition halls about Brazilian products.[91] At the center of the building was an aviary with a reflecting pool and native Brazilian plants.[92] | [91][92] |

| Canada | F. W. Williams[93] | A stucco-and-glass-block structure with a reflecting pool.[94] Inside was a main hall with exhibit spaces operated by various Canadian agencies, companies, and provincial governments, as well as a large map of Canada. A secondary hall was dedicated to Canadian industry.[93] | [94][93] |

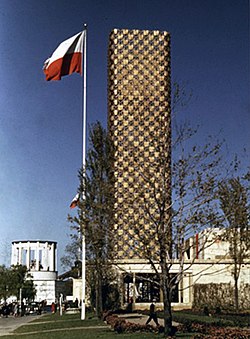

| Chile | Theodore Smith Miller[93] | A two-story, stucco-and-steel structure.[95] Inside was a hall of government and other halls dedicated to various aspects of Chilean culture. There was also an open-air deck and a garden.[96] This pavilion only operated during the 1939 season.[87][88] | [95][96] |

| Czechoslovakia | — | A structure dedicated to Czechoslovakian industry. The hall contained a mural, a decorative wood panel, and a large Czechoslovakian carpet, in addition to a restaurant and displays about several industries.[97] During the pavilion's construction, it was shortened by 45 feet (14 m).[98] | [97] |

| France | Expert and Patout[99] | A three-story modern-style structure with a roof terrace. The first floor and mezzanine had a tourist bureau, dioramas, artwork, and displays of French fashions and a 500-seat auditorium. The top floor had history, art, and furniture restaurants and a restaurant. | [99][100] |

| Great Britain | Stanley Hall and Easton & Robertson[101] | A pair of buildings with a first-floor connection. There were exhibits dedicated to various aspects of British society, in addition to a rare copy of the Magna Carta, the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, and royal silverware.[102] In addition, there was an art gallery, restaurant, movie theater, industrial exhibits, and an official-publication area.[103] This structure was one of the fair's four British pavilions.[104] | [102][103] |

| Ireland | Michael Scott[105] | A structure shaped like a large shamrock, with a sculpture representing Ireland on its facade.[106] Inside was a tourist bureau, a mural and pictures of Ireland, and exhibits of Irish products.[105] | [106][105] |

| Italy | Michele Busiri Vici[107] | A structure with a 200-foot (61 m) high waterfall dedicated to | [108][109] |

| Japan | — | A stucco structure resembling a traditional Shinto shrine, set within a Japanese garden. Japanese flower arrangement exhibits.[112] The interior had a "diplomat room" and a mural[113] and was designed by the Japanese architect and photographer Iwao Yamawaki.[114]

|

[111][112] |

| League of Nations | P. Y. de Reviers de Mauny, J. W. T. Van Erp, and George B. Post & Son[115]

|

A pentagonal structure surmounted by a circular turret measuring 100 feet (30 m) tall.[116] Inside were exhibits relating to the League of Nations and its member countries' accomplishments.[115] | [116][115] |

| Netherlands | — | This pavilion contained dioramas and demonstrations relating to the | [117] |

| Norway | — | A replica of a farm storage house; the main facade was made of glass bricks, and the second story protruded from the facade.[119] Inside the entrance, a hall of representation included an allegorical mural about Norwegian culture. There were also exhibits on Norwegian arts and crafts, society, and industry, in addition to a movie theater and a restaurant.[120] | [120][119] |

| Poland | Jan Cybulski, Jan Galinowski, and Cross & Cross[121] | A pair of structures. The main building was topped by a tower and had exhibit spaces, while the other building included a bar and restaurant. In the main building was a court of honor, a hall of science with 200 inventions, a room with two dioramas of the city of Gdynia, and a fashion display.[121] The building included 11,000 items,[122] as well as the King Jagiello Monument at the main entrance.[123] | [121][122][123] |

| Portugal | — | A structure divided into nine sections, each covering different aspects of Portuguese society.[121] There were exhibits of Portuguese art, relief maps, and photographs of Portuguese society and culture.[124] | [121][124] |

| Romania | George Cantacuzino and Octav Doicescu[125] | A four-story building with balconies modeled after Romanian monasteries.[125] Inside were exhibits about Romania's history and culture, as well as a restaurant designed in the style of a Romanian mansion.[126] The pavilion's restaurant only operated for the 1939 season.[127] | [125][126] |

| Soviet Union[b] | Boris Iofan and Karo Halabyan[128] | A semicircular structure with two wings partially enclosing a courtyard. The interior was divided into 11 sections detailing Soviet culture and history.[128] There was a replica of the Mayakovskaya station of the Moscow Metro, whose designer Alexey Dushkin received Grand Prize of the 1939 World's Fair.[129] The Soviet pavilion's courtyard contained a statue on a pylon, which was 260 feet (79 m) tall.[130] There was a separate structure with exhibits about the Soviet Union's Arctic activities.[128][131] This pavilion only operated during the 1939 season.[132] | [128][130][131] |

| Sweden | Sven Markelius and Pomerance & Breines[133] | A set of buildings around a central garden, with a restaurant, movie theater, a space for music and dance performances, and a tourist booth.[133] The pavilion displayed Swedish goods, artifacts, and artwork. There was also a full-length film about Sweden, a 10-foot-tall (3.0 m) wooden horse representing Swedish handcrafts, and a demonstration of time signals.[134] | [133][134] |

| Switzerland | — | A structure with a curved facade. Its main hall included exhibits about Swiss sports, education, spas, and geography.[135] There was also a restaurant, auditorium, beer garden, and alpine garden.[135][136] Switzerland's main pavilion was connected to the Hall of Nations' Swiss exhibit via a footbridge.[136] | [135][136] |

| Turkey | — | A structure with a stucco-and-tile facade topped by a turret.[137] The building had a courtyard with a pool, which was surrounded by displays about liquor, tobacco, and Turkish minerals.[138] Inside were displays of Turkish artwork and artifacts, a replica of Istanbul's Grand Bazaar, and a tourism bureau.[135][138] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[88] | [135][137][138] |

| United States | Howard Lovewell Cheney[139] | The Federal Building was set between two 150-foot (46 m) pylons, each decorated with sculptures. The interior was divided into 12 sections about different aspects of the United States government.[140][139] It also contained a theater and interior courtyard,[139] as well as large murals.[140] | [140][139] |

| Venezuela | Skidmore & Owings and John Moss[128] | A 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) space.[141] The structure contained exhibits about major Venezuelan products, as well as a mural and sculptures depicting these products.[128] This pavilion operated only during the 1939 season.[81] | [128] |

Hall of Nations

The following nations were located in the Hall of Nations. Some of these nations only had space in the Hall of Nations, while other nations had space both in the Hall of Nations and in a standalone pavilion.[84]

| Pavilion | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | An exposition of products made in Albania, along with an Albanian restaurant.[142] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[118] | [142] |

| Australia | A structure at the western end of the Lagoon of Nations. The building was divided into three sections each describing a different aspect of Australia's history.[143] This structure was one of the fair's four British pavilions.[104] | [143] |

| British Colonial Empire | This exhibit consisted of six sections, each dedicated to a different | [144] |

| Cuba | This exhibit displayed Cuban cultural artifacts, architecture, and products.[97] This exhibit operated only during the 1939 season.[81] | [97] |

| Czechoslovakia | An adjunct to the Czechoslovakia pavilion with exhibits on the nation's history, products, artwork, literature, and tourism. | [97] |

| Denmark | This exhibit included Danish arts and crafts, in addition to a restaurant.[97] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[118] | [97] |

| Dominican Republic | This exhibit contained a tribute to the voyages of Christopher Columbus, as well as displays about the Dominican Republic's industries. | [97] |

| Ecuador | A 5,400-square-foot (500 m2) circular space. There was a bas relief on the facade and a mural inside, both designed by Camilo Egas.[145] This exhibit displayed cocoa beans and straw hats, in addition to dioramas of Ecuadorian products and minerals.[146]

|

[145][146] |

| Finland | A 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) space.[147] This exhibit included displays about Finnish community and industry. There was also an information service, handicraft display, and restaurant.[148] | [148] |

| France | An adjunct to the France pavilion with exhibits about Overseas France. | [149] |

| Greece | This exhibit was a marble room with murals of Greek landscapes, as well as five pieces of old Greek sculptures. Native Greek products were shown in a separate space on the second floor. | [144] |

| Hungary | A set of Hungarian culture exhibits and a restaurant. Saint Istvan and a large map of Hungary.[151]

|

[150][151] |

| Iceland | This exhibit contained exhibits about Icelandic government, society, and industry. | [105] |

| Iraq | A space with elaborate multicolored decorations. This exhibit included replicas of Baghdad storefronts, models of old buildings, gold and silver jewelry, and films about Iraqi history. | [105] |

| Italy | An adjunct to the Italy pavilion. Within that space were maps of the Italian empire and a bronze statue of Mussolini .

|

[152][107] |

| Lebanon | This exhibit included a relief map of Lebanon, models of ancient Lebanese buildings, drawings by Blanche Ammoun, and exhibits about the Phoenician alphabet. | [153] |

| Lithuania | A 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) space. | [154][155] |

| Luxembourg | A 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) space.[147] This exhibit included paintings of old castles, as well as photographs of Radio Luxembourg and rural scenes.[117] | [117] |

| Mexico | A 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) space.[155] This exhibit showcased ancient Mexican artifacts, modern goods, carvings, ornaments, and photographs of modern-day Mexican infrastructure projects.[117] | [117] |

| New Zealand | This exhibit included a mockup of Sutherland Falls in New Zealand; photographs of New Zealand's landscape; and exhibits about the Māori people and New Zealand's society, education system, and industry.[120] It was one of the fair's four British pavilions.[104] | [120] |

| Pan American Union | A structure for the 21 constituent countries of the Pan-American Union and several communications and transportation companies. The governments of Bolivia, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, and Uruguay distributed informational booklets at the pavilion.[156] In the central hall was a large relief map of the Americas.[157] As part of the Good Neighbor policy at the 1939 World's Fair, an exhibit of Latin American consumer products was added in 1940.[158]

|

[156][157] |

| Paraguay | An exhibit dedicated to Paraguayan culture. This exhibit operated only during the 1940 season. | [159] |

| Peru | An exhibit about both modern and ancient Peruvian culture. This exhibit included four sections about different aspects of Peruvian culture, in addition to Inca artifacts, sculptures, paintings, gold and silver, glass, and other objects. | [121][160] |

| Portugal | An adjunct to the Portugal pavilion. It included an exhibit about attractions in Madeira, as well as dance performances and movie screenings. | [121] |

| Siam[c] / China | A 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) space.[162] For the 1939 season, this exhibit contained Thai decorations, furnishings, artwork, and handcrafts, in addition to movies about Thailand.[125]

For the 1940 season, the exhibit displayed paintings, porcelains, and other artifacts from China, and it also included a souvenir shop.[81] It originally included a mural of the U.S. flag, which was removed due to protests.[163] |

[125][162][81] |

| Southern Rhodesia | This exhibit included replicas of the Matobo National Park and Victoria Falls, in addition to information about the industries of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).[164] The exhibit operated only during part of the 1939 season.[165] | [164] |

| Soviet Union[b] | An adjunct to the Soviet pavilion, which included information about the Soviet government.[128] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[132] | [128] |

| Spain | This exhibit contained information about Spain's culture and history, a mercury fountain, and several artworks both on the facade and inside the building. | [166][167] |

| Switzerland | An adjunct to the Switzerland pavilion. It was divided into three sections describing Switzerland's history, Swiss watches, and Swiss textiles.[135] The Swiss exhibit was connected to Switzerland's main pavilion via a footbridge.[136] | [135] |

| Turkey | An adjunct to the Turkey pavilion, which provided information about Atatürk's reforms.[135] There were also two statues in addition to a bust of the Turkish president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[138] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[88] | [135][138] |

| Yugoslavia | This exhibit included folk art, photographs, a tourist bureau, and displays about various aspects of Yugoslav history and culture. There was also a sculpture representing Yugoslavia and a large map of the nation.[168] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[118] | [168] |

-

British Pavilion

-

Italian Pavilion

-

Jewish Palestine Pavilion

-

The Netherlands Garden, located in the Netherlands Pavilion exhibit

-

Polish Pavilion

-

Swedish Pavilion

-

USSR Pavilion at night

States

The fair included pavilions for 33 U.S. states and Puerto Rico.[12] While most of the pavilions surrounded a small, tree-lined lagoon in the Court of States,[169] the pavilions of New York and Florida were outside the Court of States.[170][171] Fourteen states or territories occupied their own buildings, while the rest were built by the WFC.[12] The buildings' designs generally included details that were influenced by the English, French, Georgian, and Spanish architectural styles.[169] Some of the pavilions were replicas of notable buildings or architectural styles in each state; for example, Pennsylvania's pavilion was a replica of Independence Hall, while Texas's pavilion was a copy of the Alamo Mission.[172] The New England states (with the exception of Maine) shared space in an area that was designed to resemble a New England waterfront.[171][172] The Court of States also included exhibits from many of the southeastern states, each of which had individual pavilions.[171][173]

| Pavilion | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | A pavilion with large photographs of Arizona's industries and geography on its facade.[174] Inside were displays about the state's natural resources.[175] | [174][175] |

| Arkansas | This exhibit had displays about various aspects of Arkansas, such as a diorama of Hot Springs National Park and exhibits about the state's agriculture and products. | [170][175] |

| Boy Scouts Camp | A 2-acre (0.81 ha) camp next to the Federal Building. Members of the Boy Scouts of America lived in the camp while working the fairgrounds.

|

[176][177] |

| Florida | A structure made of materials from Florida. It was surrounded by tropical plants, palm trees, and orange trees, while the building itself had 45 exhibits about various aspects of Florida's history and culture.[172][178] A motorboat transported visitors across Meadow Lake to the Florida pavilion.[179] Midway through the fair, the world's largest carillon was installed in the bell tower.[180] | [172][178][180] |

| Georgia / American Legion | An American colonial-style building covering 6,000 square feet (560 m2).[181][182] For the 1939 season, it contained exhibits about Georgia's culture and economy, including gold objects, minerals, cotton, ceramics, and wildlife.[181] For the 1940 season, this structure hosted artifacts and documents relating to the American Legion.[183] | [181][182][183] |

| Illinois | This exhibit contained a scale model of Chicago with 450,000 buildings. In addition, there were exhibits about various aspects of Illinois history, such as models of Abraham Lincoln's Springfield home. | [184][172] |

| Maine | A 4,500-square-foot (420 m2) structure.[172] During 1939, this exhibit included displays about Maine's agriculture, industry, recreation, and coastline.[171][184] During 1940, it was converted into a standalone New Hampshire pavilion,[185] which included dioramas of New Hampshire's mountains and a stream with trout swimming.[186] | [184][172][171] |

| Massachusetts | A structure with three halls about Massachusetts's past, present, and future. The halls contained dioramas, articles, documents, and products created in the state. | [184] |

| Missouri | A reproduction of the Ralls County Courthouse. Inside were dioramas about Missouri's geography, agriculture, manufacturing, and natural resources. | [187][172] |

| New England | A pair of Bullfinch-style buildings made of brick with white trim.[170][188] The focal exhibit was a 125-foot-long (38 m) schooner named Yankee.[189]

|

[170][188][189] |

| New Jersey | A replica of the Old Barracks, made of stone from New Jersey. Inside were displays about New Jersey's agriculture, industries, history, geography, and highways.[191][194] The facade of the pavilion had three murals depicting the state.[195] During the 1940 season, a diorama of a beach was added.[186] | [191][194][195] |

New York City

|

A rectangular structure near the Trylon and Perisphere.[196] Inside were dioramas, murals, models, and displays about various departments of the city government.[197][198] There were a total of 63 exhibits, as well as an auditorium.[198] | [176][197][198] |

| New York State | A temporary building outside the Meadow Lake amphitheater. The lobby included the emblems of New York's 62 counties in a grand panorama. There were also displays about departments of the New York state government; dioramas of Niagara Falls and Jones Beach State Park; a raised-relief map of New York City; busts of notable people from New York state; and various artifacts from New York state history. | [199][200] |

| North Carolina | A structure divided into three sections. The Theme Exhibit had dioramas about North Carolina's culture and economy. The Court of Tourism had color photos of visitor attractions like the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Hall of Development included displays about the state's history and inventions, including airplane models and 12 heroic-size figures. | [201][202] |

| Ohio | A Georgian-style red brick building with a revolving statue at its entrance. Inside were displays about Ohio's economy and a movie about Ohio's attractions.[201][172] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[203] | [201][172] |

| Pennsylvania | A replica of Independence Hall with three exhibit spaces.[170][171] The hall of democracy had a mural of a Pennsylvania landscape. The hall of tradition had display cases with documents, plastic mannequins wearing period clothing, and displays about notable events in Pennsylvania's history. The hall of progress included displays about the state's resources.[204] | [170][171][204] |

| Puerto Rico | A 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) building surrounding a mockup of a tropical garden.[205] Inside was a mockup of a street in San Juan, with exhibits on Puerto Rico's products, There were also replicas of an undersea garden, the Casa Blanca, and La Fortaleza.[204] For the 1940 season, new exhibits about art and industry, as well as a map of Puerto Rico, were added.[206] | [205][206][204] |

| Tennessee | A 13,000-square-foot (1,200 m2) Georgian-style building. It included photographs, mechanical displays, and dioramas about various aspects of Tennessee's culture and geography. | [192] |

| Texas | A replica of the Alamo Mission.[172] The central hall included a relief map of Texas highlighting various historical events in the state's history. The building included an auditorium in one wing, and there were lounges and meeting rooms in the other wing.[192] | [172][192] |

| Utah | This exhibit included displays and dioramas of Mormon Tabernacle.[172]

|

[172][192] |

| Virginia | A domed structure whose interior was designed to resemble Thomas Jefferson's estate at Monticello.[171] There was a main room and three smaller rooms. The smaller rooms contained an information office, a relief map of Virginia, and an area for temporary displays.[193] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[207] | [171][193] |

| Washington | A structure incorporating woods from Washington state. It had a diorama of Mount Rainier, as well as displays about Washington's natural resources. | [172][208] |

| West Virginia | A 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) structure made of woods from West Virginia.[176][209] There were displays about the state's agriculture, geography, industry, natural resources, and recreation.[176] The space was decorated extensively with murals that depicted West Virginia.[172] For the 1940 season, the building was expanded to include exhibits from 12 industries and businesses.[209] | [172][176][209] |

Food Zone

Southwest of the Government Zone was the Food Zone, composed of 13 buildings in total (the Swedish and Turkish pavilions were physically within the Food Zone but were classified as being part of the Government Zone[210]). Its focal exhibit was Food No. 3, a rhomboidal structure with four shafts representing wheat stalks.[211][212] The Food Zone included the following buildings:

| Pavilion | Architects | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy of Sport | — | A building with sports-related murals on the facade.[213][214] Inside were displays of sports trophies and sports gear, and coaches gave sports lessons.[213][215] Programs from the neighboring Court of Sport were broadcast across the U.S.[216] | [213][214][215][216] |

| American Tobacco Company | Francisco & Jacobus[213] | This building included cigarette-making machines, dioramas about tobacco production, and a movie about how cigarettes were made. | [213][217] |

| Beech-Nut Packing Company | Magill Smith[218] | A stucco structure surrounded by a lawn.[219] Inside were dioramas about coffee production,[218] in addition to a miniature circus on two revolving stages.[220] | [219][218][220] |

| Borden Company | Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith[218]

|

A 50-foot-high (15 m) glass rotunda with a dome.[221] The rotunda had 150 cows (including the original Elsie[222]) on a rotating milking machine called the Rotolactor.[221][223] There were barns next to the Rotolactor[221] and a main hall with dioramas and displays.[218] | [218][221][223] |

| Continental Baking Company | Skidmore & Owings and John Moss[224] | A structure shaped like a doughnut.[225] The curved facade was decorated with balloons, while the interiors included displays about the Continental Baking Company's products.[224] A wheat field was planted next to the pavilion.[226] | [225][224][226] |

| Distilled Spirits Exhibit | Morris Sanders (architect); Ross-Frankel and Morris Lapidus (designers)[224] | A building where distilled spirits were displayed. The exterior had a banner that depicted the revenues generated by the distilled-spirits industry. Inside was a rotunda with a revolving stage, which contained exhibits such as a model of a distillery, a laboratory, a display of bottles, and a demonstration of the distilling process.

|

[224] |

| Food Building | M. W. Del Gaudio[227]

|

A large rotunda measuring 60 feet (18 m) tall,[228] with murals by Pierre Bourdelle on its red-and-white facade.[27] Inside was a dining terrace and a large restaurant.[228] The rotunda hosted exhibits from multiple companies, with dioramas, live manufacturing demonstrations, slideshows, films, and snack bars.[227] | [228][227] |

| General Cigar Company | Ely Jacques Kahn[229] | A structure with a fan-shaped auditorium, a teletype machine displaying news headlines, scoreboards for sports games, and a lounge.

|

[229][230] |

| Heinz Dome | Leonard M. Schultze and Archibald Brown[229] | A 90-foot-tall (27 m), 150-foot-wide (46 m) dome with 19 columns on its facade.[231] Inside was a set of plaques, and a laboratory where tomatoes were grown.[232] For the 1940 season, the statue Goddess of Perfection sculpture by Raymond Barger was mounted atop the dome.[177] | [231][232][177] |

| Libby, McNeill & Libby / European Center | — | A replica of a modern ship. For the 1939 season, the pavilion's lower deck had an exhibition about the canning industry's history and a set of live shows. Libby, McNeill and Libby's products were displayed on a lounge on the upper deck.[210]

For the 1940 season, it became a bazaar-style attraction where seven dealers from different countries sold items from around the world.[233] |

[233][210] |

| National Dairy Products Corporation | De Witt Clinton Pond[210] | An exhibit about the manufacturing process of dairy and ice cream products, with a replica of a National Dairy Products Corporation added a display about the scientists Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Joseph Lister, and Louis Pasteur.[234]

|

[210][234] |

| Schaefer Center | — | A 1,000-seat restaurant serving European and American cuisines. The restaurant included murals about the history of beer, and the attached bar included murals about the restaurant's sponsor, Schaefer Beer. | [210] |

| Standard Brands Inc. | Skidmore & Owings and John Moss[235] | Four glass pavilions surrounding a 100-foot-tall (30 m) tower and a 1,000-seat amphitheater.[236] Inside the pavilion were exhibits relating to Fleischmann's Yeast, Chase & Sanborn Coffee Company, Royal Desserts, and the baking industry.[210] There were also a bar, garden, and stationary bicycles.[237] | [210][236][237] |

| Swift & Company | Skidmore & Owings[235] | A replica of an airliner. The "body" of the airliner had a lounge with a pool, while the "wings" had exhibits about the manufacturing process of | [210][238] |

Production and Distribution Zone

The Production and Distribution Zone was dedicated to showcasing industries that specialized in manufacturing and distribution.[239][240] The focal exhibit was the Consumers Building (also the Consumer Interests Building),[241] which was renamed the World of Fashion during 1940.[35] The L-shaped structure was designed by Frederic C. Hirons and Peter Copeland, with murals by Francis Scott Bradford.[242] Numerous individual companies hosted exhibitions in this region. There were also pavilions dedicated to a generic industry, such as electrical products, industrial science, pharmaceuticals, metals, and men's apparel.[243] A hall of textiles was also built for the fair.[244]

| Pavilion | Architect | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier Corporation | Reinhard & Hofmeister[245] | A 70-foot-tall (21 m) replica of an igloo.[246] The building displayed Carrier Corporation products and contained exhibits of air-conditioning installations around the world.[245] | [246][245] |

| Consolidated Edison Company of New York | Harrison & Fouilhoux[247] | A structure with a 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) "wall of water", which was illuminated in multiple colors at night.[248] Inside was a diorama of the New York metropolitan area, with over 4,000 buildings and miniature cars, trains, and elevators.[248][249] There was also an exhibit about the life of a typical Consolidated Edison Company worker.[248][250] | [248][249][250] |

| E. I. Du Pont De Nemours & Company | Walter Dorwin Teague (designer); R. J. Harper and A. M. Erickson (associates)[251] | A structure with a 105-foot-tall (32 m) tower symbolizing the equipment used in chemical laboratories. The pavilion included a hall where visitors could watch chemists work, a marionette show, and displays of DuPont products. | [251][252] |

| Eastman Kodak Company | Eugene Gerbereux (architect); Walter Dorwin Teague (designer); Stowe Myers (associate)[253] | A semicircular structure for Eastman Kodak with a triangular wing.[253] Professional color photographs were shown on a 187-by-22-foot (57.0 by 6.7 m) screen in the hall of color. There was also a hall of light, where negatives, photo murals, and motion picture equipment were shown; an exhibition corridor with two movie screens; an outdoor photograph garden; and an exhibit about the manufacturing process of cellulose acetate film.[254] During the 1940 season, a photography salon was added to the hall of light.[255] | [253][254][255] |

| Electrical Products Building / Power-Electrical and Steam | Walker & Gillette[253] | A structure with a 100-foot (30 m) pylon at its entrance. Inside were exhibits by Remington Rand, Animating Products Inc., and the White Sewing Machine Company.[253] The building was renamed in 1940.[35] | [253] |

| Electric Utilities Exhibit | Harrison & Fouilhoux[256] | A structure sponsored by 175 companies, with a 150-foot-tall (46 m) transmission tower and 40-foot-tall (12 m) waterfall. The building included replicas of a "street of yesterday" from 1892 with gas lamps, as well as an "avenue of tomorrow" with electric lamps.[253][257] There were also four electricity-themed exhibits.[258] | [253][257][258] |

| Elgin National Watch Company | — | A semicircular structure surrounding a circular observatory.[256] Inside were exhibits about the history of timekeeping devices and the process of manufacturing watches.[259] | [256][259] |

| Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States | — | A "garden of security" with an 0.5-acre (0.20 ha) outdoor amphitheater. At the center was a statue group called Protection. | [260] |

| General Electric Company | Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith[256]

|

A structure with a stainless steel lightning bolt on its facade.[256] The pavilion included an auditorium called the House of Magic; a space called Steinmetz Hall where artificial lightning demonstrations were given; and displays of General Electric products.[261][256] For the 1940 season, a new theater for demonstrations was added.[262] | [256][261][262] |

| Glass Incorporated | Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (architects); SOM (exhibits)[263] | A 25,000-square-foot (2,300 m2) rotunda surmounted by a 108-foot-tall (33 m) tower of plate glass and glass brick. The rotunda was surrounded by a patio with a glass ramp and an exhibit about glass.[264] Several glass companies hosted exhibits in the rotunda.[263] | [264][263] |

| Hall of Industrial Science | Joseph H. Freedlander, Maximilian H. Bohm, and Charles W. Beeston[265] | A structure with a 90-foot-high (27 m) lightning tower on its facade. Several companies hosted industrial-themed exhibits inside,[265] and there was also an exhibit by the New York Museum of Science and Industry.[266] This pavilion only operated during the 1939 season.[267] | [265][266] |

| Hall of Pharmacy | Pleasants Pennington, Lyman Paine, and I. Woodner-Silverman (architects); Harvey Wiley Corbett and Donald Deskey (designers)[268] | A pavilion with three sections about drugstores, the history of medicine, and family medicine cabinets.[268][269] The exhibit included a large medicine cabinet with a rotating stage.[270] The building also housed the International Drug Club's headquarters.[269] A section for the "drug store of the future" was planned but never completed.[271] | [268][269][270] |

| Man, His Clothes, His Sports / Men's Apparel Quality Guild | Starrett & van Vleck (architects); George McLaughlin (designer)[272] | A structure with a curved fin on its facade and several menswear companies' exhibits inside.[272] There was also a 400-seat auditorium and an outdoor sports facility with space for up to 4,000 spectators.[273] The building was renamed in July 1939.[271] | [272][273] |

| Metals Building / Hall of Industry | William Gehron, Benjamin Wistar Morris, and Robert B. O'Connor[274] | A triangular building with four murals by Andre Durenceau on its facade.[27] Metal companies hosted exhibits inside.[274] The building was renamed in 1940.[35] | [274] |

| Petroleum Industry Exhibition | Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith (architects); Gilbert Rohde (designer)[275]

|

An 80-foot-tall (24 m) blue-green pyramidal structure, supported by four 20-foot-high (6.1 m) replicas of | [276][275] |

| United States Steel subsidiaries | York and Sawyer (architects); Walter Dorwin Teague (designer); G. F. Harrell (associate)[275] | A dome measuring 132 feet (40 m) wide and 66 feet (20 m) high, with 28,000 square feet (2,600 m2) of space across two floors.[278] There were dioramas, murals, and live demonstrations about the history of steel, in addition to a second-floor terrace.[275][278] Behind the building was a garden with a steel trellis.[275] More displays were added for the 1940 season, emphasizing the steel manufacturing process and steel industry.[279] | [275][278][279] |

| Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company | Skidmore & Owings and John Moss[275] | A horseshoe-shaped structure with two glass-enclosed halls. Westinghouse Time Capsule, a tube with contemporary objects, which was not to be opened till the year 6939.[280]

|

[258][275][280] |

Transportation Zone

The Transportation Zone was located west of the Theme Center, across the

| Pavilion | Architect | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aviation Building | William Lescaze and J. Gordon Carr[284] | A building divided into three sections, dedicated to travel, defense, and recreation and commerce. Four planes were suspended from the ceiling.[284] There were also three U.S. Army and three U.S. Navy planes.[285] | [284][285] |

| B. F. Goodrich Company | William Berle Thompson and Wilbur Watson & Associates[286] | A streamlined structure, surrounding an elliptical courtyard where driving performances were hosted daily.[286] Above the pavilion's main entrance was a tower with a guillotine that crushed used tires. Inside were displays of automobiles, as well as interactive exhibits.[287] | [286][287] |

| Firestone Tire and Rubber Company | Wilbur Watson & Associates (architects); George W. McLaughlin (designer)[288] | An L-shaped structure with a central rotunda and a 100-foot-tall (30 m) spire. Inside were mockups of a tire factory and an American farm. | [288] |

| Ford Motor Company | Albert Kahn Inc. (architect); Walter Dorwin Teague (designer)[289] | A structure dedicated to the Ford Motor Company's products, which was topped by a 25-foot-tall (7.6 m) statue of the god Mercury.[289][290] The entrance hall had Ford vehicles, a mural, and a large map, while the industrial hall had a turntable.[289] There was also a garden court,[289] as well as a spiral ramp called the Road of Tomorrow, which traveled in and out of the building.[290] | [289][290] |

| General Motors | Albert Kahn Inc. (architect); Norman Bel Geddes (designer)[291] | A 7-acre (2.8 ha) pavilion with four structures, each rising four to six stories. The structures included a casino of science with animated displays and a genuine locomotive engine.[291] The 36,000-square-foot (3,300 m2) Futurama exhibit, designed by Norman Bel Geddes, included a diorama of a fictional American landscape.[292] There was also a research laboratory and animated displays about General Motors cars.[291] Sun decks, ramps, plazas, and roof gardens were spread throughout the pavilion.[293] | [291][292][293] |

| Marine Transportation Building | Ely Jacques Kahn and Muschenheim & Brounn[283] | An 80-foot-tall (24 m) structure shaped like the bows of two ocean liners.[294] The center of the building had an interactive world map showing steamship routes, and there were also model ships and exhibits about marine safety. Marine-transport companies had ticket booths and exhibits within the pavilion as well.[283] This exhibit only operated during the 1939 season.[267] | [294][283] |

| Railroads | Eggers & Higgins (architects), Raymond Loewy (designer)[284] | A structure operated by the Eastern Railroads Presidents' Conference. model train set[296] and a 110,000-square-foot (10,000 m2) exhibition building with a replica of a roundhouse.[295] The building's facade included railway-related murals. The interior contained railway exhibits, a stage show, and exhibits of actual locomotives such as the Coronation Scot locomotive.[297]

|

[295][296][284][297] |

Amusement Area

The Amusement Area was located south of World's Fair Boulevard, along 230 acres (93 ha).

Due to the popularity of nude or seminude performances at the

| Structure | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Admiral Byrd's Penguin Island | A replica of a penguin habitat. | [310] |

| Aerial Joyride | A ride with 16 swinging cars. | [310] |

| Amazons in No-Man's Land | A walk-through show where guests could see Amazonian women take part in contests. | [310] |

| Archery Range | An archery range with 28 stalls. | [311] |

| Arctic Girl's Tomb of Ice | A show where a woman was encased in a large block of ice. | [312] |

| Artist Village | An attraction where guests could watch artists paint, sketch, or carve artwork. Guests could also buy silhouette drawings. | [312] |

| Auto Dodgem | A ride with 52 bumper cars. | [312] |

| Ballantine Three Ring Inn | A 2,000-seat restaurant with performers.[312] There was a 500-seat cafeteria, 500-seat bar, and 1,000-seat main dining room.[313] The building itself had a steep gable roof and was surrounded by gardens.[314] | [312][313][314] |

| Bel Geddes' Mirror Show | A show where a woman performed in a mirrored room. | [312] |

| Bendix Lama Temple | A 28,000-piece full-sized replica of the 1767 Potala temple in Vincent Bendix.[315] The Temple had previously been exhibited at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair, called "Century of Progress".[316] Attendance was disappointing in 1939. As a result, in 1940, a provocative show was added to the temple,[317] which involved multiple nude women.[318]

|

[315] |

| Billy Rose's Aquacade | A massive curved amphitheater at the north end of Meadow Lake.[319] The amphitheater hosted Billy Rose's Aquacade, a musical and water extravaganza with an orchestra to accompany the spectacular synchronized swimming performance.[312] | [320] |

| Bobsled | A bobsled ride.

|

[320] |

| Brass Rail | This company operated four restaurants throughout the Amusement Zone. | [320] |

| Caruso Restaurant | An Italian restaurant seating 300 people. | [320] |

| Cavalcade of Centaurs | A rodeo with performers from around the world. | [321] |

| Centipede | A ride that traversed a bumpy track. | [322] |

| Children's World | A 7-acre (2.8 ha) play area for children.[323][324] The area had two playgrounds with various rides for children aged 4–14.[324] There were also attractions such as a clothes exhibit, miniature railway, bookstore, and doll palace.[323] For the 1940 season, the area was downsized.[325] | [323][324][325] |

| Congress of World's Beauties | An outdoor enclosure and 1,500-seat theater where beautiful women performed. | [326] |

| Crystal Palace of 1939 | An exhibit space detailing the history of past world's fairs. | [327] |

| Cuban Village | A show with performances by Cubans. | [328] |

| Drive-a-Drome | A car ride. | [328] |

| Enchanted Forest | A show incorporating elements from fairy tales. | [328] |

| Fireworks stands | Five thousand seats on the eastern shore of Meadow Lake. | [329] |

| Frank Buck's Jungleland | A show and miniature zoo with various wild animals. | [328][299][330] |

| Gang Busters | An exhibit about efforts to fight organized crime in the U.S. | [331] |

| Giant's Causeway | A replica of an Irish landscape. | [331] |

| George Washington Camp | An 11-acre (4.5 ha) reenactment of a military camp. | [332][333] |

| Giant Safety Roller Coaster | A 3,000-foot-long (910 m) roller coaster measuring 70 feet (21 m) high, with three 24-seat trains. | [331][334] |

| Heineken's on the Zuider Zee | A replica of a Dutch landscape, covering around 16,000 square feet (1,500 m2). | [335] |

| Infant Incubator Inc. | A building with | [336][337] |

| Jitterbug | A car ride. | [338] |

| Laff Land | A building with a "tower of light" and a stage show inside. | [338] |

| Laff in the Dark | A dark ride. | [338] |

| Life Savers Parachute Tower | An attraction where passengers could be dropped off a 250-foot-tall (76 m) tower before being slowed down by parachutes.[338][339] There were originally 11 chutes, but a 12th chute was added in 1940.[340] | [338][339][340] |

| Live Monsters | A bamboo-covered structure with reptile exhibits. | [341] |

| Living Magazine Covers | A show featuring beautiful women whose faces were displayed on magazine covers. | [341] |

| Mayflower Doughnut Corporation | This company operated a restaurant in the Amusement Area. | [341] |

| Merrie England | A replica of an old English village. | [341] |

| The Meteor | A ride in which visitors were flipped at 90-degree angles within a sphere. | [341] |

| Midget Auto Race | A racetrack ride. | [341] |

| Morris Gest's Miracle Town | A tiny town covering about 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) and featuring around 120 little people. | [341][342] |

| National Advisory Committee | A structure for the National Advisory Committee, which included a main hall, lounges, offices, meeting rooms, and a dining room. | [343] |

| National Cash Register Company | A 40-foot-high (12 m) cash register–shaped building with exhibits and a cash register. | [344] |

| Nature's Mistakes | A freak show–style attraction. | [344] |

| New York Zoological Society | An attraction with rare animals from around the world, as well as a film series. | [345] |

| Old New York | A 2-acre (0.81 ha) area themed to New York City in the 1890s, with replicas of notable structures, theatrical performances, and a restaurant. | [346] |

| Over the Top | A Roll-O-Plane attraction. | [347] |

| Palm Beach Club | A nightclub. | [348] |

| Penny Arcade | An arcade with coin-operated games .

|

[349] |

| Photomatic Studios | A building where visitors could have photographs taken of themselves. | [349] |

| Queensborough Host House | A clubhouse for local social clubs. | [349] |

| Salvador Dalí's Living Pictures | A show where women performed in front of three-dimensional artworks by Salvador Dalí.[349] The pavilion contained a number of unusual sculptures and statues as well as live nearly-nude performers posing as statues.[350] | [349][350] |

| Savoy Ballroom Theatre | A theater with 20-minute-long dance performances and swing bands .

|

[349] |

| Seminole Village | A show with Seminole Native American people. | [351] |

| Serpentine | A ride with tubs that traveled on a twisting track. | [352] |

| Silver Streak | A ride that traveled on a circular track at speeds of up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h). | [353] |

| Skee Ball and Chime Ball | A Skee-Ball bowling alley. | [353] |

| Ski Jump | An attraction that offered winter sports classes during the 1940 season. | [354] |

| Sky Ride | An observation tower rising 200 feet (61 m). | [353] |

| Snapper | A ride with tubs that traveled on a twisting track. | [353] |

| Sons of the American Revolution | A building with American Revolutionary War memorabilia and meeting rooms. | [353] |

| Strange as It Seems | A show with unusual characters based on the cartoon strip Strange as It Seems. | [355] |

| Stratoship | A ride with bullet-shaped vehicles flying around a tower. | [355] |

| Sun Valley | A set of ski slopes, jumps, and slides. There was also an alpine town with replica mountains, a waterfall, an ice rink, and a restaurant. | [355][233] |

| Theatre of Time and Space | A theater that simulated a trip to space. | [356] |

| Victoria Falls | A replica of Victoria Falls. | [357] |

| Wild West Show | A show with an arena, bar, restaurant, and frontier town. | [299] |

| World's Fair Hall of Music | A 2,500-seat auditorium. | [299][332] |

Other exhibits

Standalone exhibits

There were two focal exhibits that were not located within any zone. The first was the Medical and Public Health Building on Constitution Mall and the Avenue of Patriots (immediately northeast of the Theme Center).[358] This structure contained a massive "Hall of Man" designed by I. Woodner-Silverman, which was dedicated to the human body, and a "Hall of Medical Science" designed by Otto Teegan, which was dedicated to medical professions and devices.[358][359] The first floor of the building had a 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) private club for medical professionals, with a lounge.[360]

The Science and Education Building, located on a curved portion of Hamilton Place between the Avenue of Patriots and Washington Square, just north of the Medical and Public Health Building. The building was not used to teach science, but it contained an auditorium and several exhibits on science and education.[361] The pavilion also had an exhibit on kindergartens during the 1940 season.[362]

Other structures

At the west end of the fairground was the administration building; this structure included a first-floor hall with artifacts about the fair, in addition to offices and a cafeteria.[363] The building's facade had a 27-foot-tall (8.2 m) relief of a woman.[364] During the fairground's construction, the administration building contained mockups of industry-themed exhibits,[365] and it was also used to test out lighting systems.[22] The fair also had a hospitality center staffed mainly by women, This building had an auditorium, lounge, restaurant, dressing rooms, lockers, and offices for national and international organizations.[366] Twenty American breweries operated the Hometown Restaurant, a 53,000-square-foot (4,900 m2) eatery with 2,000 seats and a 205-foot-long (62 m) bar.[367]

The fairground had a bank branch operated by

Unbuilt exhibits

The original plans called for a veterans' temple of peace next to the state-themed buildings.[371] South of the Food Zone, there was originally supposed to be a fisheries building with a stadium.[372] The WFC had also announced plans for a "freedom pavilion" in January 1939, depicting Germany before the Nazi government takeover,[373] but the plans were abandoned because of a lack of time and money.[374] Syria withdrew plans for a pavilion in April 1939 due to internal unrest;[375] the proposed Hall of Fashion was canceled the same month, and the Hall of Fashion building was used as an event space.[376]

El Salvador was originally supposed to have a pavilion at the fair as well, but these plans were canceled in favor of a pavilion at the Golden Gate International Exposition.[377] In advance of the 1940 season, some of the state exhibits were expanded, while others were shuttered.[186] Some states considered hosting exhibits at the 1939 World's Fair before canceling their plans. Nevada's exhibit was canceled in June 1939 due to labor-related troubles,[378] and California scrapped plans for an exhibit after the New York State Legislature refused to provide funds for a New York state pavilion at the Golden Gate International Exposition.[379] Oregon withdrew from the fair due to disputes over where the Oregon pavilion would have been located.[380]

Preserved pavilions and attractions

The WFC mandated that almost all structures be removed within four months of the fair's closure.[381] The vast majority of structures were dismantled or moved shortly after the fair's final day.[382]

Seven structures were initially preserved as part of the park.

Many of the World's Fair amusement rides were sold to Luna Park at Coney Island;[392] the Parachute Jump was sold and relocated to Steeplechase Park, also in Coney Island.[393] One building from the fair's Town of Tomorrow exhibit was moved to New Jersey in 1955;[394] another building from that exhibit was turned into an office for the Queens Botanical Garden before it burned down in 1956.[395] The fair's Christian Science pavilion became the Church of Christ, Scientist, in Freeport, New York,[396] and the Belgian Building, which was rebuilt at Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia.[397] Pieces of exhibits were also saved: A large portion of the General Motors pavilion's Futurama exhibit was displayed at Rockefeller Center's New York Museum of Science and Industry,[398] and the Ford Cycle of Production exhibit was moved to Dearborn, Michigan.[399] The Bendix Golden Temple was disassembled and placed in storage for many years, but various proposals to reconstruct it have failed.[400]

Critical reception

When the fair was being developed, The New York Times described the buildings as "a cross between functional architecture and fair architecture", with "undeniably spectacular" designs.[24] Lynn Hardesty of The Washington Post wrote that the buildings "have astonished even the most sophisticated of art critics" because they were so colorful.[29] Conversely, the critic Lewis Mumford lambasted the design of the fairground, calling it a "half-baked order of a Renaissance plan" that introduced disarray to the fair.[401][402] Talbot Hamlin regarded the WFC buildings as having "neither monumentality or gaiety",[20][21] though he believed that the individual exhibitors' pavilions were "in themselves interesting and beautiful".[403] Royal Cortissoz of the New York Herald Tribune felt that, although the fair's muralists were skilled, many of the murals on the buildings appeared to be "arbitrarily affixed", rather than essential components of the buildings' designs.[404]

When the fair opened, a writer for the Architectural Review said the WFC buildings lacked a logical design and that they did not give a light-hearted or imposing impression.[20] The architect Harvey Wiley Corbett saw the buildings as disharmonious, saying that "each building screams at the visitor in its own different voice"; according to Corbett, it was hard to derive any single conclusion from the fair as a result.[405] On the other hand, a New York Times writer said that the state and U.S. territory exhibit buildings were "in itself of outstanding interest".[170] A New York Herald Tribune writer, in mid-1939, wrote that the foreign exhibit buildings were "an absorbing and genuine display of the attractions all the countries offer".[406]

In 1964, one writer for The New York Times wrote that "the exhibits were appreciated for things their sponsors never suspected", since they provided places for guests to relax.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Also known as the Jewish Palestine pavilion.[63]

- ^ a b Listed as "USSR" on official maps[84]

- ^ This pavilion was renamed the Thailand pavilion in mid-1939, after Siam's English name was changed to Thailand.[161]

- ^ Namely the New York City Building, Aquacade amphitheater, B.F. Goodrich Pavilion, House of Jewels, Masterpieces of Art building, Japanese Pavilion, and Polish Pavilion's tower.[11][382]

Citations

- from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024; Weer, William (October 9, 1936). "Model of Exposition Shown to Directors". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 12. Archivedfrom the original on July 1, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- from the original on June 21, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- .

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- ^ Whalen, Grover A. (January 1939). "The New York World's Fair of 1939: Fair Progress in a Nutshell". Bankers' Magazine. Vol. 138, no. 1. p. 27. ProQuest 124369078.

- ^ Monaghan 1939, pp. 46–47.

- ^ "Vast Queens Park Rising on Fair Site". The New York Times. December 6, 1936. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 730.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-8478-1122-9. Archivedfrom the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- from the original on June 21, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 731.

- ^ a b c Hamlin 1938, p. 675.

- ^ a b "Whalen Describes New Lighting Developed For World's Fair". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 55, no. 88. November 3, 1937. pp. 23–24. ProQuest 1699951135.

- ^ a b c "$156,000,000 Show: Eleven Gates Ready to Swing at the N. Y. World's Fair: Spectacle". Newsweek. Vol. 13, no. 18. May 1, 1939. pp. 46, 49. ProQuest 1796267678.

- ^ from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 827.

- ^ Hamlin 1938, p. 676.

- ^ .

- from the original on August 2, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ Hamlin 1938, pp. 678–679.

- ^ Appleton Read, Helen (September 1, 1938). "Murals at the World's Fair...". Harper's Bazaar. Vol. 71, no. 2713. p. 104-105, 129. ProQuest 1871468222.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 57.

- ^ Cotter 2009, p. 39.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 58–61.

- ^ a b c d e f "Change Names of Buildings at Fair". Daily News. April 2, 1940. p. 384. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 61.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 61–63.

- ^ a b "N. Y. World's Fair: Building Devoted To Business Systems And Insurance Firms". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 58, no. 84. May 1, 1939. p. 8. ProQuest 1677066535.

- ISBN 978-0-292-73723-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Exposition Publications 1939, p. 64.

- ^ a b Robertson, Bruce (May 1, 1939). "Television Motif Marks New York Fair". Broadcasting, Broadcast Advertising. Vol. 16, no. 9. pp. 20–21. ProQuest 1014928343.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 65.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Cotter 2009, p. 79.

- ^ Monaghan 1939, pp. 85–101.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, p. 67.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c d e f Exposition Publications 1939, p. 70.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 71.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 74.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 76.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 76–77.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Exposition Publications 1939, p. 77.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Monaghan 1939, p. 136.

- ^ "1940 Jewish Palestine Pavilion Catalog". www.1939nyworldsfair.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 77–78.

- ^ McAll, Reginald L. (February 1, 1939). "Great Church Music Program at Exposition" (PDF). The Diapason. 30 (3): 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 79.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Monaghan 1939, pp. 116–117.

- ^ .

- from the original on August 23, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Cotter 2009, p. 55.

- from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 826.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ "U. S. Practically In Concession Business For N. Y. World Fair". Variety. Vol. 132, no. 12. November 30, 1938. pp. 1, 54. ProQuest 1476066504.

- ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1243039852; Shalett, Sidney M. (January 2, 1940). "'People's' Common Dedicated at Fair; Opening Fashion Building at the Fair". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 92.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 94.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 95.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 95–97.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 97.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 97–100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Exposition Publications 1939, p. 100.

- from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 102–103.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, p. 1023.

- ^ a b "World's Fair in New York: Opening to-day by President 29 Warships "at Home" British Pavilion Ready". The Observer. April 30, 1939. p. 17. ProQuest 481671177.

- ^ a b Monaghan 1939, p. 129.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d e Exposition Publications 1939, p. 105.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 105–107.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Fortuna 2019, p. 197.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Wood 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Čapková, Helena, (2014)Transnational Networkers—Iwao and Michiko Yamawaki and the Formation of Japanese Modernist Design in Journal of Design History vol.27, no.4

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 108.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Exposition Publications 1939, p. 110.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d e f g Exposition Publications 1939, p. 112.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d e Exposition Publications 1939, p. 113.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Exposition Publications 1939, p. 117.

- ISBN 978-2-86770-068-2.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019; "Boro Veterans Plan to Give Fair a Flagpole". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 31, 1939. p. 7. Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 115.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Exposition Publications 1939, p. 116.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 119.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 93.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 104.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, p. 103.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 104–105.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Fortuna 2019, p. 198.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 108–110.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 111–112.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ "World's Fair Center Planned To Promote Latin-American Trade: Government Official, Retailers, And Representatives From Abroad Will Meet Wednesday". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 60, no. 59. March 25, 1940. p. 7. ProQuest 1653161922; "Fair Gives Plans for Pan-america; U.S. Retail Group Would Help Display of Latin Wares to Stimulate Trade". The New York Times. March 28, 1940. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 114.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 114–115.

- from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 118.

- ^ from the original on August 2, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- ^ from the original on July 31, 2024. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Williams, Gladstone (February 3, 1938). "World Fair Exhibit for South Planned: Southern States to Work as Closely Knit Organisation on Displays". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 4. ProQuest 502928077.

- ^ from the original on July 31, 2024. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e Exposition Publications 1939, p. 131.

- ^ from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Exposition Publications 1939, p. 122.

- .

- ^ a b "Big Carillon For Fair to Be Built by Deagan" (PDF). The Diapason. 30 (2): 2. January 1, 1939. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b Hines, William M. Jr. (November 5, 1939). "Georgia Wins Acclaim At New York Fair". p. SM3. ProQuest 503180846.

- ^ from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 123.

- from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 123–125.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f Exposition Publications 1939, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 130.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- .

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 125–126.

- from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 126.

- .

- .

- ^ a b c d Exposition Publications 1939, p. 127.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- .

- ^ Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 130–131.

- ^ from the original on August 1, 2024. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Exposition Publications 1939, p. 90.

- ^ Monaghan 1939, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Cotter 2009, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e Exposition Publications 1939, p. 83.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Exposition Publications 1939, p. 85.

- ^ a b "Merchandise Machines: Beech-nut to Exhibit at New York's World Fair". The Billboard. Vol. 51, no. 1. January 7, 1939. p. 60. ProQuest 1032186266.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Exposition Publications 1939, p. 86.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, pp. 87–89.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c Exposition Publications 1939, p. 89.

- from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.

- ^ from the original on September 13, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2024.