1964 Democratic Party presidential primaries

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

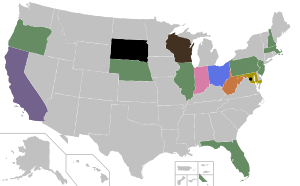

Gold denotes a state won by Daniel Brewster. Purple denotes a state won by Pat Brown. Green denotes a state won by Lyndon B. Johnson. Blue denotes a state won by Albert S. Porter. Orange denotes a state won by Jennings Randolph. Brown denotes a state won by John W. Reynolds. Pink denotes a state won by Matthew E. Welsh. Black denotes a state won by unpledged delegates. Grey denotes a state that did not hold a primary. | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

From March 10 to June 2, 1964, voters of the

Primary race

Johnson became

Only two potential candidates threatened Johnson's attempts to unite the party. The first was Governor

As the 1964 nomination was considered a foregone conclusion, the primaries received little press attention outside of Wallace's entry into the race. Despite threats of an independent run in the

Background

The goodwill generated by the assassination of Kennedy incident gave Johnson tremendous popularity. He enjoyed strong support against the bitterly divided Republicans; polls in January 1964 showed him leading Republican challengers

Despite condemnation from media outlets — in 1965, when reporter Theodore H. White published The Making of the President, 1964, he referred to Wallace as a "narrow-minded, grotesquely provincial man"

Primaries

| Date | State(s) |

|---|---|

| March 10 | New Hampshire |

| April 7 | Wisconsin |

| April 14 | Illinois |

| April 21 | New Jersey |

| April 28 | Massachusetts |

| May 2 | Texas1 |

| May 5 | District of Columbia, Indiana, Ohio |

| May 12 | Nebraska, West Virginia |

| May 15 | Oregon |

| May 19 | Maryland |

| May 26 | Florida |

| June 2 | California, North Dakota |

| 1 No primary was authorized on the Democratic side; the Republicans held their primary as scheduled.[9] | |

At the time, the transition from traditional party conventions to the modern

Although Johnson faced no real opposition for the Democratic nomination, a plan had been hatched by a number of southerners to run

The "Bobby problem"

Johnson faced pressure from some within the Democratic Party to name

The potential need for a Johnson–Kennedy ticket was ultimately eliminated by the Republican nomination of conservative Barry Goldwater. With Goldwater as his opponent, Johnson's choice of vice president was all but irrelevant; opinion polls had revealed that, while Kennedy was an overwhelming first choice among Democrats, any choice made less than a 2% difference in a general election that already promised to be a landslide. When attempts to ease Kennedy out of the running failed, Johnson searched for a way to eliminate him with minimal party discord, and eventually announced that none of his cabinet members would be considered for the position. Kennedy instead mounted a successful run for United States Senate in New York.[17]

Wisconsin

Wallace had hinted at a possible run numerous times, telling one reporter, "If I ran outside the South and got 10%, it would be a victory. It would shake their eyeteeth in Washington."

Reynolds continued to dismiss Wallace's candidacy, which was denounced by media outlets, clergy, trade unions such as the

Wallace's strong showing was due in part to his appeal to ethnic neighborhoods made up of immigrants from countries such as

Indiana

Wallace next appeared on the ballot in

As Wallace excoriated what he called "sweeping federal encroachment" on the gradual process of desegregation, described the Civil Rights Act as a "back-door open-occupancy bill", and appeared alongside a popular Catholic bishop in support of a constitutional amendment to allow

Wallace received nearly 30% of the vote, below some expectations but nonetheless startling given the level of opposition.[12][33] The total was 376,023 to 172,646 votes — Wallace's worst showing in any state.[34]

In an article in The British Journal of Sociology, Michael Rogin observed a heavy correlation between significant

Maryland

Racially polarized Maryland was Wallace's best showing. There the Johnson supporters struggled to find a suitable candidate after Governor

Although race played a significant factor in Wallace's support elsewhere,[7] his strength in Maryland came from the galvanized Eastern Shore, where some estimates put his support among whites as high as 90%. Riots in Cambridge had erupted over the repeal of an equal access law, and as the rioters clashed with the National Guard, civil rights leader Gloria Richardson led peaceful demonstrations against the measure.[40] At the behest of aid Bill Jones, Wallace reluctantly kept a speaking engagement in Cambridge, where he was confronted by some 500 black protesters. When a baby was thought to have died from the tear gas used by police, it seemed a public relations disaster to the Wallace campaign, but the coroner's report concluded the baby had died of a congenital heart defect. Opponents nonetheless attempted to use the incident and the neo-Nazi National States' Rights Party's description of Wallace as the "last chance for the white voter" against him, but Wallace continued to gain momentum, and The Baltimore Sun observed the distinct possibility that he would win the state.[38][39]

With voter turnout up by 40%, nearly 500,000 votes were cast, of which Brewster received 53% to Wallace's 43%. Wallace, who won outright among white voters, reportedly said, "If it hadn't been for the nigger bloc vote, we'd have won it all."[41] Indeed, Wallace won 15 of Maryland's 23 counties, and only a combination of double the usual African-American turnout and liberal votes from Montgomery and Prince George's Counties prevented a Wallace victory.[41]

Candidates

The following political leaders were candidates for the 1964 Democratic presidential nomination:

Nominee

| Candidate | Most recent office | Home state | Campaign

Withdrawal date |

Popular vote | Contests won | Running mate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyndon B. Johnson |

|

President of the United States (1963–1969) |

Texas |

(Campaign) Secured nomination: August 27, 1964 |

1,106,999 (17.8%) |

9 | Hubert Humphrey | |

Other major candidates

These candidates participated in multiple state primaries or were included in multiple major national polls.

| Candidate | Most recent office | Home state | Campaign

Withdrawal date |

Popular vote | Contests won | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| George Wallace |

|

Governor of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979, 1983–1987) |

Alabama |

(Campaign) | 672,984 (10.8%) |

0 | |

Results

| State | Lyndon Johnson (including surrogates)

|

Robert F. Kennedy | George Wallace | Unpledged | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 10 | New Hampshire

|

95.26% | 1.58% | 3.16% | ||

| April 7 | Wisconsin | 66.25% | 33.75% | |||

| April 14 | Illinois | 91.63% | 3.23% | 4.20% | 0.94% | |

| April 21 | New Jersey | 82.30% | 8.31% | 9.39% | ||

| April 28 | Massachusetts | 72.91% | 18.96% | 0.68% | 7.45% | |

| May 5 | Indiana | 64.94% | 29.82% | |||

| Ohio | 100.00% | |||||

| Washington, D.C. | 100.00% | |||||

| May 12 | Nebraska | 89.30% | 1.74% | 8.96% | ||

| West Virginia | 100.00% | |||||

| May 15 | Oregon | 99.50% | 0.50% | |||

| May 19 | Maryland | 53.14% | 42.75% | 4.11% | ||

| May 26 | Florida | 100.00% | ||||

| June 2 | California | 100.00% | ||||

| North Dakota | 100.00% |

Candidates:

- President Lyndon B. Johnson - 1,106,999 (17.7%)

- George Wallace - 672,984 (10.8%)

Johnson surrogates:

- Unpledged delegates - 2,705,290 (43.3%)

- John W. Reynolds- 522,405 (8.4%)

- Albert S. Porter - 493,619 (7.9%)

- Matthew E. Welsh - 376,023 (6.0%)

- Daniel Brewster - 267,106 (4.3%)

Write-ins:

- Robert F. Kennedy - 36,258 (0.5%)

- Henry Cabot Lodge - 8,495 (0.1%)

- William W. Scranton- 8,156 (0.1%)

- Edward M. Kennedy- 1,065 (<0.1%)

- Others - 50,224 (0.8%)

In the state of California, two slates of unpledged delegates appeared on the ballot. The slate controlled by Pat Brown received 1,693,813 votes (68%), while the slate controlled by Sam Yorty received 798,431 votes (32%). In West Virginia, where Jennings Randolph campaigned on Johnson's behalf, the only option on the ballot was "unpledged delegates at large", which received 131,432 votes (100%). South Dakota and the District of Columbia similarly had unpledged delegates as the only option. Wallace notably received 12,104 votes in Pennsylvania and 3,751 votes in Illinois despite visiting neither state, although Kennedy received a comparable portion of the vote in both states.[9][42]

Vice-presidential choice and Wallace's withdrawal

With Robert F. Kennedy out of the way, the question of Johnson's choice of running mate provided some suspense for an otherwise uneventful convention.[43] However, Johnson also became concerned that Kennedy might use a scheduled speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention to create a groundswell of emotion among the delegates to nominate him as Johnson's running mate; Johnson prevented this by scheduling Kennedy's speech on the last day of the convention, by which time the vice-presidential nomination would have been made. Shortly after the convention, Kennedy decided to leave Johnson's cabinet and run for the U.S. Senate in New York, where he won the general election in November. Johnson chose Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, a liberal and civil rights activist, as his running mate.[44]

Meanwhile, the Republicans had nominated the conservative Goldwater, who shared Wallace's opposition to the Civil Rights Act on the basis of states' rights and found considerable support among southerners. This caused a precipitous drop in support for Wallace's threatened general election campaign, and on June 18, Wallace biographer Dan T. Carter notes that Goldwater gave "a brief speech which — in substance if not tone — could have been written by George Wallace."[45] By July 13, Gallup polls showed that Wallace support in a general election match-up had plummeted to below 3% outside the south. Even in the south, he polled third in a three-way race against Johnson and Goldwater. Goldwater reportedly welcomed Wallace's support but firmly refused him a spot as vice-presidential candidate.[46] With a conservative already facing off against Johnson, Wallace stayed his nascent plans for a third-party run until the 1968 election, ending his campaign with an appearance on Face the Nation on July 19; however, he did not endorse Goldwater.[47] In the general election, Goldwater repudiated Wallace and denied courting his vote, which Wallace took as a personal insult.[46]

Convention

Despite his insistence that he remained undecided about running, Johnson had meticulously planned the convention to ensure it went smoothly. Aside from a minor controversy over the Mississippi delegation (see

Johnson went on to win the general election in a landslide, only losing the Deep South states of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina, as well as Goldwater's home state of Arizona.[49]

See also

Notes

References

- Specific

- ^ Donaldson, p. 78.

- ^ Lesher, p. 261.

- ^ Carter (p. 197) names the black man as Gordon O. Du Bois II, grandson of W. E. B. Du Bois, while Lesher (p. 263) calls him "a black man of uncertain connections". The exact wording of Wallace's response also varies slightly between sources, but it is agreed that Wallace "brought the house down" in Donaldson's words (p. 101).

- ^ Donaldson, p. 102.

- ^ White, p. 235. Also quoted in Donaldson, p. 95.

- ^ Durr, p. 120.

- ^ a b White, pp. 233-235; Kolkey, pp. 162-209; Rogin, pp.33-41. See also White, chapter eight, "Riots in the Streets: The Politics of Chaos".

- ^ Donaldson, pp. 95, 225.

- ^ a b c d Congressional Quarterly, Inc., pp. 176-178.

- ^ White, p. 255. Dallek, (pp. 171-172) describes Johnson's self-doubts and a withdrawal statement drafted as late as August 1964. However, "Most everyone thought he was being too clever by half. There was no chance Johnson wouldn't run. He was playing a political game, or so they believed."

- ^ White, p. 271; Donaldson, pp. 93-95.

- ^ a b Lesher, p. 295.

- ^ Lesher, p. 303.

- ^ Carter, p. 369.

- ^ Donaldson, p. 184.

- ^ Donaldson, pp. 184-187.

- ^ Donaldson, pp. 187-193; Savage, pp. 224-228; White, p. 257.

- ^ Lesher, p. 273.

- ^ According to Lesher (pp. 273–274), the press conference at which Reynolds fielded the question was the first time the Wallace camp had heard of the Herbstreiths, while Carter (pp. 202–204) describes Lloyd Herbstreith phoning Wallace's skeptical staff after he and Dolores had heard Wallace speak.

- ^ Carter, pp. 202–204

- ^ Lesher, p. 276.

- ^ Carter, pp. 204, 208.

- ^ Lesher, pp. 282–284.

- ^ Carter, pp. 206–208; Savage, p. 216

- ^ Lesher, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Rogin, p. 31.

- ^ Gugin, p. 342

- ^ a b Carter, p. 210; Lesher, p. 293.

- ^ Gray, p. 393

- ^ Savage, p. 219.

- ^ Durr, p. 119; Lesher, pp. 289-293.

- ^ Gray, p. 394

- ^ Bennett, Mark (2008-04-28). "MARK BENNETT: The Indiana Primary carries an interesting background into this". TribStar.com. The Tribune-Star. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ^ Gugin, p. 343

- ^ Rogin, p. 30.

- ^ Rogin, p. 32.

- ^ Carter, p. 212; Lesher, pp. 296-297.

- ^ a b Durr, p. 123.

- ^ a b Lesher, pp. 296-301.

- ^ Carter, p. 214.

- ^ a b Carter, p. 215; Lesher, pp. 303-304.

- ^ Lesher, p. 305.

- ^ Dallek, p. 174.

- ^ Donaldson, p. 200.

- ^ Carter, p. 218.

- ^ a b Carter, pp. 219-224.

- ISBN 0-313-31119-6.

- ^ Donaldson, pp. 71-105, 227.

- ^ Congressional Quarterly, Inc., pp. 179-180.

- Bibliography

- Carter, Dan T. (1995). The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-8071-2597-0.

- Congressional Quarterly, Inc. (1997). Presidential Elections, 1789-1996. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly. ISBN 1-56802-065-1.

- Dallek, Robert (2004). Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515920-9.

- Donaldson, Gary (2003). Liberalism's Last Hurrah: The Presidential Campaign of 1964. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-1119-8.

- Durr, Kenneth D (2003). Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2764-9.

- Gray, Ralph D (1995). Indiana History: A Book of Readings. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-32629-X.

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

- Lesher, Stephan (1994). George Wallace: American Populist. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-62210-6.

- Kolkey, Jonathan Martin (1983). The New Right, 1960-1968: With Epilogue, 1969-1980. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America.

- Rogin, Michael (March 1969). "Politics, Emotion, and the Wallace Vote". The British Journal of Sociology. 20 (1). Blackwell Publishing: 27–49. JSTOR 588997.

- Savage, Sean J. (2004). JFK, LBJ, and the Democratic Party. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6169-6.

- White, Theodore H (1965). The Making of the President, 1964. New York: Atheneum Publishers.

Further reading

- Carter, Dan T. (1996). From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963-1994. The Walter Lynwood Fleming lectures in southern history. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-19-507680-X.

- Hewitt, Roger (2005). White Backlash and the Politics of Multiculturalism. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81768-4.