Bromine compounds

Bromine compounds are compounds containing the element bromine (Br). These compounds usually form the -1, +1, +3 and +5 oxidation states. Bromine is intermediate in reactivity between chlorine and iodine, and is one of the most reactive elements. Bond energies to bromine tend to be lower than those to chlorine but higher than those to iodine, and bromine is a weaker oxidising agent than chlorine but a stronger one than iodine. This can be seen from the standard electrode potentials of the X2/X− couples (F, +2.866 V; Cl, +1.395 V; Br, +1.087 V; I, +0.615 V; At, approximately +0.3 V). Bromination often leads to higher oxidation states than iodination but lower or equal oxidation states to chlorination. Bromine tends to react with compounds including M–M, M–H, or M–C bonds to form M–Br bonds.[1]

| X | XX | HX | BX3 | AlX3 | CX4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 159 | 574 | 645 | 582 | 456 |

| Cl | 243 | 428 | 444 | 427 | 327 |

| Br | 193 | 363 | 368 | 360 | 272 |

| I | 151 | 294 | 272 | 285 | 239 |

Hydrogen bromide

The simplest compound of bromine is

- 2 P + 6 H2O + 3 Br2 → 6 HBr + 2 H3PO3

- H3PO3 + H2O + Br2 → 2 HBr + H3PO4

At room temperature, hydrogen bromide is a colourless gas, like all the hydrogen halides apart from

Unlike

2 ions – the latter, in any case, are much less stable than the bifluoride ions (HF−

2) due to the very weak hydrogen bonding between hydrogen and bromine, though its salts with very large and weakly polarising cations such as Cs+ and NR+

4 (R = Me, Et, Bun) may still be isolated. Anhydrous hydrogen bromide is a poor solvent, only able to dissolve small molecular compounds such as nitrosyl chloride and phenol, or salts with very low lattice energies such as tetraalkylammonium halides.[3]

Other binary bromides

Nearly all elements in the periodic table form binary bromides. The exceptions are decidedly in the minority and stem in each case from one of three causes: extreme inertness and reluctance to participate in chemical reactions (the noble gases, with the exception of xenon in the very unstable XeBr2; extreme nuclear instability hampering chemical investigation before decay and transmutation (many of the heaviest elements beyond bismuth); and having an electronegativity higher than bromine's (oxygen, nitrogen, fluorine, and chlorine), so that the resultant binary compounds are formally not bromides but rather oxides, nitrides, fluorides, or chlorides of bromine. (Nonetheless, nitrogen tribromide is named as a bromide as it is analogous to the other nitrogen trihalides.)[4]

Bromination of metals with Br2 tends to yield lower oxidation states than chlorination with Cl2 when a variety of oxidation states is available. Bromides can be made by reaction of an element or its oxide, hydroxide, or carbonate with hydrobromic acid, and then dehydrated by mildly high temperatures combined with either low pressure or anhydrous hydrogen bromide gas. These methods work best when the bromide product is stable to hydrolysis; otherwise, the possibilities include high-temperature oxidative bromination of the element with bromine or hydrogen bromide, high-temperature bromination of a metal oxide or other halide by bromine, a volatile metal bromide,

- FeCl3 + BBr3 (excess) → FeBr3 + BCl3

When a lower bromide is wanted, either a higher halide may be reduced using hydrogen or a metal as a reducing agent, or thermal decomposition or disproportionation may be used, as follows:[4]

- 3 WBr5 + Al 3 WBr4 + AlBr3

- EuBr3 + 1/2 H2 → EuBr2 + HBr

- 2 TaBr4 TaBr3 + TaBr5

Most of the bromides of the pre-transition metals (groups 1, 2, and 3, along with the lanthanides and actinides in the +2 and +3 oxidation states) are mostly ionic, while nonmetals tend to form covalent molecular bromides, as do metals in high oxidation states from +3 and above. Silver bromide is very insoluble in water and is thus often used as a qualitative test for bromine.[4]

Bromine halides

The halogens form many binary,

2, BrCl−

2, BrF+

2, BrF+

4, and BrF+

6. Apart from these, some pseudohalides are also known, such as cyanogen bromide (BrCN), bromine thiocyanate (BrSCN), and bromine azide (BrN3).[5]

The pale-brown bromine monofluoride (BrF) is unstable at room temperature, disproportionating quickly and irreversibly into bromine, bromine trifluoride, and bromine pentafluoride. It thus cannot be obtained pure. It may be synthesised by the direct reaction of the elements, or by the comproportionation of bromine and bromine trifluoride at high temperatures.[5] Bromine monochloride (BrCl), a red-brown gas, quite readily dissociates reversibly into bromine and chlorine at room temperature and thus also cannot be obtained pure, though it can be made by the reversible direct reaction of its elements in the gas phase or in carbon tetrachloride.[4] Bromine monofluoride in ethanol readily leads to the monobromination of the aromatic compounds PhX (para-bromination occurs for X = Me, But, OMe, Br; meta-bromination occurs for the deactivating X = –CO2Et, –CHO, –NO2); this is due to heterolytic fission of the Br–F bond, leading to rapid electrophilic bromination by Br+.[4]

At room temperature, bromine trifluoride (BrF3) is a straw-coloured liquid. It may be formed by directly fluorinating bromine at room temperature and is purified through distillation. It reacts violently with water and explodes on contact with flammable materials, but is a less powerful fluorinating reagent than chlorine trifluoride. It reacts vigorously with boron, carbon, silicon, arsenic, antimony, iodine, and sulfur to give fluorides, and will also convert most metals and many metal compounds to fluorides; as such, it is used to oxidise uranium to uranium hexafluoride in the nuclear power industry. Refractory oxides tend to be only partially fluorinated, but here the derivatives KBrF4 and BrF2SbF6 remain reactive. Bromine trifluoride is a useful nonaqueous ionising solvent, since it readily dissociates to form BrF+

2 and BrF−

4 and thus conducts electricity.[6]

Bromine pentafluoride (BrF5) was first synthesised in 1930. It is produced on a large scale by direct reaction of bromine with excess fluorine at temperatures higher than 150 °C, and on a small scale by the fluorination of potassium bromide at 25 °C. It also reacts violently with water and is a very strong fluorinating agent, although chlorine trifluoride is still stronger.[7]

Polybromine compounds

Although dibromine is a strong oxidising agent with a high first ionisation energy, very strong oxidisers such as peroxydisulfuryl fluoride (S2O6F2) can oxidise it to form the cherry-red Br+

2 cation. A few other bromine cations are known, namely the brown Br+

3 and dark brown Br+

5.[8] The tribromide anion, Br−

3, has also been characterised; it is analogous to triiodide.[5] Neutral Br

2 molecules are incorporated into an adduct with the anionic copper-bromine complex Cu2Br62-.[9]

Bromine oxides and oxoacids

| E°(couple) | a(H+) = 1 (acid) |

E°(couple) | a(OH−) = 1 (base) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Br2/Br− | +1.052 | Br2/Br− | +1.065 |

| HOBr/Br− | +1.341 | BrO−/Br− | +0.760 |

| BrO− 3/Br− |

+1.399 | BrO− 3/Br− |

+0.584 |

| HOBr/Br2 | +1.604 | BrO−/Br2 | +0.455 |

| BrO− 3/Br2 |

+1.478 | BrO− 3/Br2 |

+0.485 |

| BrO− 3/HOBr |

+1.447 | BrO− 3/BrO− |

+0.492 |

| BrO− 4/BrO− 3 |

+1.853 | BrO− 4/BrO− 3 |

+1.025 |

So-called "bromine dioxide", a pale yellow crystalline solid, may be better formulated as bromine perbromate, BrOBrO3. It is thermally unstable above −40 °C, violently decomposing to its elements at 0 °C. Dibromine trioxide, syn-BrOBrO2, is also known; it is the anhydride of hypobromous acid and bromic acid. It is an orange crystalline solid which decomposes above −40 °C; if heated too rapidly, it explodes around 0 °C. A few other unstable radical oxides are also known, as are some poorly characterised oxides, such as dibromine pentoxide, tribromine octoxide, and bromine trioxide.[12]

The four

Br2 + H2O ⇌ HOBr + H+ + Br− Kac = 7.2 × 10−9 mol2 l−2 Br2 + 2 OH− ⇌ OBr− + H2O + Br− Kalk = 2 × 108 mol−1 l

Hypobromous acid is unstable to disproportionation. The hypobromite ions thus formed disproportionate readily to give bromide and bromate:[10]

3 BrO− ⇌ 2 Br− + BrO−

3K = 1015

Bromous acids and

- BrO−

3 + 5 Br− + 6 H+ → 3 Br2 + 3 H2O

There were many failed attempts to obtain perbromates and perbromic acid, leading to some rationalisations as to why they should not exist, until 1968 when the anion was first synthesised from the radioactive

Organobromine compounds

Like the other carbon–halogen bonds, the C–Br bond is a common functional group that forms part of core

Organobromides are typically produced by additive or substitutive bromination of other organic precursors. Bromine itself can be used, but due to its toxicity and volatility, safer brominating reagents are normally used, such as N-bromosuccinimide. The principal reactions for organobromides include dehydrobromination, Grignard reactions, reductive coupling, and nucleophilic substitution.[15]

Organobromides are the most common organohalides in nature, even though the concentration of bromide is only 0.3% of that for chloride in sea water, because of the easy oxidation of bromide to the equivalent of Br+, a potent electrophile. The enzyme

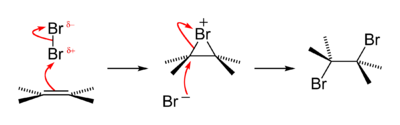

An old qualitative test for the presence of the alkene functional group is that alkenes turn brown aqueous bromine solutions colourless, forming a bromohydrin with some of the dibromoalkane also produced. The reaction passes through a short-lived strongly electrophilic bromonium intermediate. This is an example of a halogen addition reaction.[18]

See also

- Category:Bromine compounds

- Organobromine compounds

References

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 804–9

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 809–12

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 812–6

- ^ a b c d e f g Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 821–4

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 824–8

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 828–31

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 832–5

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 842–4

- .

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 853–9

- ISBN 978-0-8493-8671-8, archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2021, retrieved 25 August 2015

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 850–1

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 862–5

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 871–2

- ^ .

- PMID 15548002.

- doi:10.1039/a900201d.

- ISBN 978-0-19-927029-3.