Berbers

This article has an unclear citation style. (December 2022) |

| |

|---|---|

Berbers, or the Berber peoples,

They are indigenous to the Maghreb region of North Africa, where they live in scattered communities across parts of Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and to a lesser extent Tunisia, Mauritania, northern Mali and northern Niger.[41][43][44] Smaller Berber communities are also found in Burkina Faso and Egypt's Siwa Oasis.[45][46][47]

Descended from Stone Age tribes of North Africa, accounts of the Imazighen were first mentioned in

Berbers are divided into several diverse ethnic groups and Berber languages, such as

Names and etymology

The

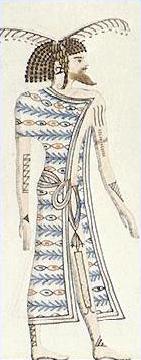

Tribal titles such as Barabara and Beraberata appear in Egyptian inscriptions of 1700 and 1300 B.C, and the Berbers were probably intimately related with the Egyptians in very early times. Thus the true ethnic name may have become confused with Barbari, the designation used by classical conquerors.

The plural form Imazighen is sometimes also used in English.[43][57] While Berber is more widely known among English-speakers, its usage is a subject of debate, due to its historical background as an exonym and present equivalence with the Arabic word for "barbarian".[58][59][44][60] Historically, Berbers did not refer to themselves as Berbers/Amazigh but had their own terms to refer to themselves. For example, the Kabyle use the term "Leqbayel" to refer to their own people, while the Chaoui identified as "Ishawiyen", instead of Berber/Amazigh.[53]

Stéphane Gsell proposed the translation "noble/free" for the term Amazigh based on Leo Africanus's translation of "awal amazigh" as "noble language" referring to Berber languages; this definition remains disputed and is largely seen as an undue extrapolation.[61][62][63] The term Amazigh also has a cognate in the Tuareg "Amajegh", meaning noble.[64][61] "Mazigh" was used as a tribal surname in Roman Mauretania Caesariensis.[62][65]

Abraham Isaac Laredo proposes that the term Amazigh could be derived from "Mezeg", which is the name of Dedan of Sheba in the Targum.[66][61]

The medieval Arab historian

The

Prehistory

The

Prehistoric Tifinagh inscriptions were found in the Oran region.[71] During the pre-Roman era, several successive independent states (Massylii) existed before King Masinissa unified the people of Numidia.[72][73][74][full citation needed]

History

The areas of North Africa that have retained the Berber language and traditions best have been, in general, Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Much of Berber culture is still celebrated among the cultural elite in Morocco and Algeria, especially in the

Origins

Mythology

According to the Roman historian

Other sources

According to the Al-Fiḥrist, the Barber (i.e. Berbers) comprised one of seven principal races in Africa.[81]

The medieval Tunisian scholar

They belong to a powerful, formidable, brave and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen – like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans. The men who belong to this family of peoples have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.

— Ibn Khaldun[83]

Scientific

As of about 5000 BC, the populations of North Africa were descended primarily from the

Additionally, genomic analysis found that Berber and other Maghreb communities have a high frequency of an ancestral component that originated in the Near East. This Maghrebi element peaks among Tunisian Berbers.[87] This ancestry is related to the Coptic/Ethio-Somali component, which diverged from these and other West Eurasian-affiliated components before the Holocene.[88]

In 2013, Iberomaurusian skeletons from the prehistoric sites of

Human fossils excavated at the Ifri n'Amr ou Moussa site in Morocco have been

The late-Neolithic Kehf el Baroud inhabitants were modelled as being of about 50% local North African ancestry and 50%

Antiquity

The great tribes of Berbers in classical antiquity (when they were often known as ancient Libyans)[92][d] were said to be three (roughly, from west to east): the Mauri, the Numidians near Carthage, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauretania, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians occupied the regions between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both the Mauri and the Numidians had significant sedentary populations living in villages, and their peoples both tilled the land and tended herds. The Gaetulians lived to the near south, on the northern margins of the Sahara, and were less settled, with predominantly pastoral elements.[93][94][95]: 41f

For their part, the Phoenicians (Semitic-speaking Canaanites) came from perhaps the most advanced multicultural sphere then existing, the western coast of the Fertile Crescent region of West Asia. Accordingly, the material culture of Phoenicia was likely more functional and efficient, and their knowledge more advanced, than that of the early Berbers. Hence, the interactions between Berbers and Phoenicians were often asymmetrical. The Phoenicians worked to keep their cultural cohesion and ethnic solidarity, and continuously refreshed their close connection with Tyre, the mother city.[92]: 37

The earliest Phoenician coastal outposts were probably meant merely to resupply and service ships bound for the lucrative metals trade with the Iberians,

In fact, for a time their numerical and military superiority (the best horse riders of that time) enabled some

Eventually, the Phoenician trading stations would evolve into permanent settlements, and later into small towns, which would presumably require a wide variety of goods as well as sources of food, which could be satisfied through trade with the Berbers. Yet, here too, the Phoenicians probably would be drawn into organizing and directing such local trade, and also into managing agricultural production. In the 5th century BC, Carthage expanded its territory, acquiring

Lack of contemporary written records makes the drawing of conclusions here uncertain, which can only be based on inference and reasonable conjecture about matters of social nuance. Yet it appears that the Phoenicians generally did not interact with the Berbers as economic equals, but employed their agricultural labour, and their household services, whether by hire or indenture; many became

sharecroppers.[92]: 86

For a period, the Berbers were in constant revolt, and in 396 there was a great uprising.

Thousands of rebels streamed down from the mountains and invaded Punic territory, carrying the serfs of the countryside along with them. The Carthaginians were obliged to withdraw within their walls and were besieged.

Yet the Berbers lacked cohesion; and although 200,000 strong at one point, they succumbed to hunger, their leaders were offered bribes, and "they gradually broke up and returned to their homes".[96]: 125, 172 Thereafter, "a series of revolts took place among the Libyans [Berbers] from the fourth century onwards".[92]: 81

The Berbers had become involuntary 'hosts' to the settlers from the east, and were obliged to accept the dominance of Carthage for centuries. Nonetheless, therein they persisted largely unassimilated,[citation needed] as a separate, submerged entity, as a culture of mostly passive urban and rural poor within the civil structures created by Punic rule.[103] In addition, and most importantly, the Berber peoples also formed quasi-independent satellite societies along the steppes of the frontier and beyond, where a minority continued as free 'tribal republics'. While benefiting from Punic material culture and political-military institutions, these peripheral Berbers (also called Libyans)—while maintaining their own identity, culture, and traditions—continued to develop their own agricultural skills and village societies, while living with the newcomers from the east in an asymmetric symbiosis.[e][105]

As the centuries passed, a society of Punic people of Phoenician descent but born in Africa, called Libyphoenicians emerged there. This term later came to be applied also to Berbers acculturated to urban Phoenician culture.[92]: 65, 84–86 Yet the whole notion of a Berber apprenticeship to the Punic civilization has been called an exaggeration sustained by a point of view fundamentally foreign to the Berbers.[94]: 52, 58 A population of mixed ancestry, Berber and Punic, evolved there, and there would develop recognized niches in which Berbers had proven their utility. For example, the Punic state began to field Berber–Numidian cavalry under their commanders on a regular basis. The Berbers eventually were required to provide soldiers (at first "unlikely" paid "except in booty"), which by the fourth century BC became "the largest single element in the Carthaginian army".[92]: 86

Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society.[citation needed] Thus, when the Greeks under Agathocles (361–289 BC) of Sicily landed at Cape Bon and threatened Carthage (in 310 BC), there were Berbers, under Ailymas, who went over to the invading Greeks.[96]: 172 [f] During the long Second Punic War (218–201 BC) with Rome (see below), the Berber King Masinissa (c. 240 – c. 148 BC) joined with the invading Roman general Scipio, resulting in the war-ending defeat of Carthage at Zama, despite the presence of their renowned general Hannibal; on the other hand, the Berber King Syphax (d. 202 BC) had supported Carthage. The Romans, too, read these cues, so that they cultivated their Berber alliances and, subsequently, favored the Berbers who advanced their interests following the Roman victory.[106]

Carthage was faulted by her ancient rivals for the "harsh treatment of her subjects" as well as for "greed and cruelty".[92]: 83 [g][107] Her Libyan Berber sharecroppers, for example, were required to pay half of their crops as tribute to the city-state during the emergency of the First Punic War. The normal exaction taken by Carthage was likely "an extremely burdensome" one-quarter.[92]: 80 Carthage once famously attempted to reduce the number of its Libyan and foreign soldiers, leading to the Mercenary War (240–237 BC).[96]: 203–209 [108][109] The city-state also seemed to reward those leaders known to deal ruthlessly with its subject peoples, hence the frequent Berber insurrections. Moderns fault Carthage for failure "to bind her subjects to herself, as Rome did [her Italians]", yet Rome and the Italians held far more in common perhaps than did Carthage and the Berbers. Nonetheless, a modern criticism is that the Carthaginians "did themselves a disservice" by failing to promote the common, shared quality of "life in a properly organized city" that inspires loyalty, particularly with regard to the Berbers.[92]: 86–87 Again, the tribute demanded by Carthage was onerous.[110]

[T]he most ruinous tribute was imposed and exacted with unsparing rigour from the subject native states, and no slight one either from the cognate Phoenician states. ... Hence arose that universal disaffection, or rather that deadly hatred, on the part of her foreign subjects, and even of the Phoenician dependencies, toward Carthage, on which every invader of Africa could safely count as his surest support. ... This was the fundamental, the ineradicable weakness of the Carthaginian Empire ...[110]

The Punic relationship with the majority of the Berbers continued throughout the life of Carthage. The unequal development of material culture and social organization perhaps fated the relationship to be an uneasy one. A long-term cause of Punic instability, there was no melding of the peoples. It remained a source of stress and a point of weakness for Carthage. Yet there were degrees of convergence on several particulars, discoveries of mutual advantage, occasions of friendship, and family.[111]

The Berbers gain historicity gradually during the

Roman-era Cyrenaica became a center of

Numidia

Numidia (202 – 46 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a Roman province and being a Roman client state. The kingdom was located on the eastern border of modern Algeria, bordered by the Roman province of Mauretania (in modern Algeria and Morocco) to the west, the Roman province of Africa (modern Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. Its people were the Numidians.

The name Numidia was first applied by

In 206 BC, the new king of the Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax, of the Masaesyli, switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war, the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa. At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of Carthaginian territory, and southeast as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage except towards the sea.[114]

Masinissa was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118 BC, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, of Berber origin, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarreled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.

After Jugurtha defeated him in open battle, Adherbal fled to Rome for help. The Roman officials, allegedly due to bribes but perhaps more likely out of a desire to quickly end conflict in a profitable client kingdom, sought to settle the quarrel by dividing Numidia into two parts. Jugurtha was assigned the western half. However, soon after, conflict broke out again, leading to the Jugurthine War between Rome and Numidia.

Mauretania

In antiquity, Mauretania (3rd century BC – 44 BC) was an ancient Mauri Berber kingdom in modern Morocco and part of Algeria. It became a client state of the

Middle Ages

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches, Butr and Baranis (known also as Botr and Barnès), descended from Mazigh ancestors, who were themselves divided into tribes and subtribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several fully independent tribes (e.g., Sanhaja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmuda, Kutama, Awraba, Barghawata, etc.).[115][full citation needed][116]

The Mauro-Roman Kingdom was an independent Christian Berber kingdom centred in the capital city of Altava (present-day Algeria) which controlled much of the ancient Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis. Berber Christian communities within the Maghreb all but disappeared under Islamic rule. The indigenous Christian population in some Nefzaoua villages persisted until the 14th century.[117]

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb and

Before the eleventh century, most of Northwest Africa had become a Berber-speaking

Besides the Arabian influence, North Africa also saw an influx, via the Barbary slave trade, of Europeans, with some estimates placing the number of European slaves brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period to be as high as 1.25 million.[118] Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, traders, and nomads from other parts of Africa also left impressions upon the Berber people.

Islamic conquest

The first Arabian military expeditions into the Maghreb, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. These early forays from a base in Egypt occurred under local initiative rather than under orders from the central caliphate. But when the seat of the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus, the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty ruling from 661 to 750) recognized that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. In 670, therefore, an Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi established the town of Qayrawan about 160 kilometres south of modern Tunis and used it as a base for further operations.

The spread of Islam among the Berbers did not guarantee their support for the Arab-dominated caliphate, due to the discriminatory attitude of the Arabs. The ruling Arabs alienated the Berbers by taxing them heavily, treating converts as second-class Muslims, and, worst of all, by enslaving them. As a result, widespread opposition took the form of

After the revolt, Ibadis established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. But others, such as

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands,

In al-Andalus under the Umayyad governors

The Muslims who invaded the

English medievalist Roger Collins suggests that if the forces that invaded the Iberian peninsula were predominantly Berber, it is because there were insufficient Arab forces in Africa to maintain control of Africa and attack Iberia at the same time.[121]: 98 Thus, although north Africa had only been conquered about a dozen years previously, the Arabs already employed forces of the defeated Berbers to carry out their next invasion.[121]: 98 This would explain the predominance of Berbers over Arabs in the initial invasion. In addition, Collins argues that Berber social organization made it possible for the Arabs to recruit entire tribal units into their armies, making the defeated Berbers excellent military auxiliaries.[121]: 99 The Berber forces in the invasion of Iberia came from Ifriqiya or as far away as Tripolitania.[122]

Governor As-Samh distributed land to the conquering forces, apparently by tribe, though it is difficult to determine from the few historical sources available.[121]: 48–49 It was at this time that the positions of Arabs and Berbers were regularized across the Iberian peninsula. Berbers were positioned in many of the most mountainous regions of Spain, such as Granada, the Pyrenees, Cantabria, and Galicia. Collins suggests this may be because some Berbers were familiar with mountain terrain, whereas the Arabs were not.[121]: 49–50 By the late 710s, there was a Berber governor in Leon or Gijon.[121]: 149 When Pelagius revolted in Asturias, it was against a Berber governor. This revolt challenged As-Samh's plans to settle Berbers in the Galician and Cantabrian mountains, and by the middle of the eighth century it seems there was no more Berber presence in Galicia.[121]: 49–50 The expulsion of the Berber garrisons from central Asturias, following the battle of Covadonga, contributed to the eventual formation of the independent Asturian kingdom.[122]: 63

Many Berbers were settled in what were then the frontier lands near Toledo, Talavera, and Mérida,[121]: 195 Mérida becoming a major Berber stronghold in the eighth century.[121]: 201 The Berber garrison in Talavera would later be commanded by Amrus ibn Yusuf and was involved in military operations against rebels in Toledo in the late 700s and early 800s.[121]: 210 Berbers were also initially settled in the eastern Pyrenees and Catalonia.[121]: 88–89, 195 They were not settled in the major cities of the south, and were generally kept in the frontier zones away from Cordoba.[121]: 207

Roger Collins cites the work of Pierre Guichard to argue that Berber groups in Iberia retained their own distinctive social organization.[121]: 90 [123][124] According to this traditional view of Arab and Berber culture in the Iberian peninsula, Berber society was highly impermeable to outside influences, whereas Arabs became assimilated and Hispanized.[121]: 90 Some support for the view that Berbers assimilated less comes from an excavation of an Islamic cemetery in northern Spain, which reveals that the Berbers accompanying the initial invasion brought their families with them from north Africa.[122][125]

In 731, the eastern Pyrenees were under the control of Berber forces garrisoned in the major towns under the command of Munnuza. Munnuza attempted a Berber uprising against the Arabs in Spain, citing mistreatment of Berbers by Arabic judges in north Africa, and made an alliance with Duke Eudo of Aquitaine. However, governor Abd ar-Rahman attacked Munnuza before he was ready, and, besieging him, defeated him at Cerdanya. Because of the alliance with Munnuza, Abd ar-Rahman wanted to punish Eudo, and his punitive expedition ended in the Arab defeat at Poitiers.[121]: 88–90

By the time of the governor Uqba, and possibly as early as 714, the city of Pamplona was occupied by a Berber garrison.[121]: 205–206 An eighth-century cemetery has been discovered with 190 burials all according to Islamic custom, testifying to the presence of this garrison.[121]: 205–206 [126] In 798, however, Pamplona is recorded as being under a Banu Qasi governor, Mutarrif ibn Musa. Ibn Musa lost control of Pamplona to a popular uprising. In 806 Pamplona gave its allegiance to the Franks, and in 824 became the independent Kingdom of Pamplona. These events put an end to the Berber garrison in Pamplona.[121]: 206–208

Medieval Egyptian historian Al-Hakam wrote that there was a major Berber revolt in north Africa in 740–741, led by Masayra. The Chronicle of 754 calls these rebels Arures, which Collins translates as 'heretics', arguing it is a reference to the Berber rebels' Ibadi or Khariji sympathies.[121]: 107 After Charles Martel attacked Arab ally Maurontus at Marseille in 739, governor Uqba planned a punitive attack against the Franks, but news of a Berber revolt in north Africa made him turn back when he reached Zaragoza.[121]: 92 Instead, according to the Chronicle of 754, Uqba carried out an attack against Berber fortresses in Africa. Initially, these attacks were unsuccessful; but eventually Uqba destroyed the rebels, secured all the crossing points to Spain, and then returned to his governorship.[121]: 105–106

Although Masayra was killed by his own followers, the revolt spread and the Berber rebels defeated three Arab armies.

The Berbers marched south in three columns, simultaneously attacking Toledo, Cordoba, and the ports on the Gibraltar strait. However, Ibn Qatan's sons defeated the army attacking Toledo, the governor's forces defeated the attack on Cordoba, and Balj defeated the attack on the strait. After this, Balj seized power by marching on Cordoba and executing Ibn Qatan.[121]: 108 Collins points out that Balj's troops were away from Syria just when the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads broke out, and this may have contributed to the fall of the Umayyad regime.[121]: 121

In Africa, the Berbers were hampered by divided leadership. Their attack on Kairouan was defeated, and a new governor of Africa,

Roger Collins argues that the Great Berber revolt facilitated the establishment of the Kingdom of Asturias and altered the demographics of the Berber population in the Iberian peninsula, specifically contributing to the Berber departure from the northwest of the peninsula.[121]: 150–151 When the Arabs first invaded the peninsula, Berber groups were situated in the northwest. However, due to the Berber revolt, the Umayyad governors were forced to protect their southern flank and were unable to mount an offense against the Asturians. Some presence of Berbers in the northwest may have been maintained at first, but after the 740s there is no more mention of the northwestern Berbers in the sources.[121]: 150–151, 153–154

In al-Andalus during the Umayyad emirate

When the Umayyad Caliphate was overthrown in 750, a grandson of Caliph Hisham, Abd ar-Rahman, escaped to north Africa[121]: 115 and hid among the Berbers of north Africa for five years. A persistent tradition states that this is because his mother was Berber[121]: 117–118 and that he first took refuge with the Nafsa Berbers, his mother's people. As the governor Ibn Habib was seeking him, he then fled to the more powerful Zenata Berber confederacy, who were enemies of Ibn Habib. Since the Zenata had been part of the initial invasion force of al-Andalus, and were still present in the Iberian peninsula, this gave Abd ar-Rahman a base of support in al-Andalus,[121]: 119 although he seems to have drawn most of his support from portions of Balj's army that were still loyal to the Umayyads.[121]: 122–123 [122]: 8

Abd ar-Rahman crossed to Spain in 756 and declared himself the legitimate Umayyad ruler of al-Andalus. The governor,

As emir of al-Andalus, Abd ar-Rahman I faced persistent opposition from Berber groups, including the Zenata. Berbers provided much of Yusuf's support in fighting Abd ar-Rahman. In 774, Zenata Berbers were involved in a Yemeni revolt in the area of Seville.[121]: 168 Andalusi Berber Salih ibn Tarif declared himself a prophet and ruled the Bargawata Berber confederation in Morocco in the 770s.[121]: 169

In 768, a

Roger Collins notes that both modern historians and ancient Arab authors have had a tendency to portray Shaqya as a fanatic followed by credulous fanatics, and to argue that he was either self-deluded or fraudulent in his claim of Fatimid descent.[121]: 169 However, Collins considers him an example of the messianic leaders that were not uncommon among Berbers at that time and earlier. He compares Shaqya to Idris I, a descendant of Ali accepted by the Zenata Berbers, who founded the Idrisid dynasty in 788, and to Salih ibn Tarif, who ruled the Bargawata Berber in the 770s. He also compares these leaders to pre-Islamic leaders Dihya and Kusaila.[121]: 169–170

In 788, Hisham I succeeded Abd ar-Rahman as emir; but his brother Sulayman revolted and fled to the Berber garrison of Valencia, where he held out for two years. Finally, Sulayman came to terms with Hisham and went into exile in 790, together with other brothers who had rebelled with him.[121]: 203, 208 In north Africa, Sulayman and his brothers forged alliances with local Berbers, especially the Kharijite ruler of Tahert. After the death of Hisham and the accession of Al-Hakam, Hisham's brothers challenged Al-Hakam for the succession. Abd Allah[who?] crossed over to Valencia first in 796, calling on the allegiance of the same Berber garrison that sheltered Sulayman years earlier.[122]: 30 Crossing to al-Andalus in 798, Sulayman based himself in Elvira (now Granada), Ecija, and Jaen, apparently drawing support from the Berbers in these mountainous southern regions. Sulayman was defeated in battle in 800 and fled to the Berber stronghold in Mérida, but was captured before reaching it and executed in Cordoba.[121]: 208

In 797, the Berbers of Talavera played a major part in defeating a revolt against Al-Hakam in Toledo.[122]: 32 A certain Ubayd Allah ibn Hamir of Toledo rebelled against Al-Hakam, who ordered Amrus ibn Yusuf, the commander of the Berbers in Talavera, to suppress the rebellion. Amrus negotiated in secret with the Banu Mahsa faction in Toledo, promising them the governorship if they betrayed Ibn Hamir. The Banu Mahsa brought Ibn Hamir's head to Amrus in Talavera. However, there was a feud between the Banu Mahsa and the Berbers of Talavera, who killed all the Banu Mahsa. Amrus sent the heads of the Banu Mahsa along with that of Ibn Hamir to Al-Hakam in Cordoba. The Toledo rebellion was sufficiently weakened that Amrus was able to enter Toledo and convince its inhabitants to submit.[122]: 32–33

Collins argues that unassimilated Berber garrisons in al-Andalus engaged in local vendettas and feuds, such as the conflict with the Banu Mahsa.

Berber groups were involved in the rebellion of Umar ibn Hafsun from 880 to 915.[122]: 121–122 Ibn Hafsun rebelled in 880, was captured, then escaped in 883 to his base in Bobastro. There he formed an alliance with the Banu Rifa' tribe of Berbers, who had a stronghold in Alhama.[122]: 122 He then formed alliances with other local Berber clans, taking the towns of Osuna, Estepa, and Ecija in 889. He captured Jaen in 892.[122]: 122 He was only defeated in 915 by Abd ar-Rahman III.[122]: 125

Throughout the ninth century, the Berber garrisons were one of the main military supports of the Umayyad regime.[122]: 37 Although they had caused numerous problems for Abd ar-Rahman I, Collins suggests that by the reign of Al-Hakam the Berber conflicts with Arabs and native Iberians meant that Berbers could only look to the Umayyad regime for support and patronage and developed solid ties of loyalty to the emirs. However, they were also difficult to control, and by the end of the ninth century the Berber frontier garrisons disappear from the sources. Collins says this might be because they migrated back to north Africa or gradually assimilated.[122]: 37

In al-Andalus during the Umayyad caliphate

New waves of Berber settlers arrived in al-Andalus in the 10th century, brought as mercenaries by Abd ar-Rahman III, who proclaimed himself caliph in 929, to help him in his campaigns to restore Umayyad authority in areas that had overthrown it during the reigns of the previous emirs.[122]: 103, 131, 168 These new Berbers "lacked any familiarity with the pattern of relationships" that had existed in al-Andalus in the 700s and 800s;[122]: 103 thus they were not involved in the same web of traditional conflicts and loyalties as the previously already existing Berber garrisons.[122]: 168

New frontier settlements were built for the new Berber mercenaries. Written sources state that some of the mercenaries were placed in Calatrava, which was refortified.[122]: 168 Another Berber settlement called Vascos, west of Toledo, is not mentioned in the historical sources, but has been excavated archaeologically. It was a fortified town, had walls, and a separate fortress or alcazar. Two cemeteries have also been discovered. The town was established in the 900s as a frontier town for Berbers, probably of the Nafza tribe. It was abandoned soon after the Castilian occupation of Toledo in 1085. The Berber inhabitants took all their possessions with them.[122]: 169 [127]

In the 900s, the Umayyad caliphate faced a challenge from the Fatimids in North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate of the 10th century was established by the Kutama Berbers.[128][129] After taking the city of Kairouan and overthrowing the Aghlabids in 909, the Mahdi Ubayd Allah was installed by the Kutama as Imam and Caliph,[130][131] which posed a direct challenge to the Umayyad's own claim.[122]: 169 The Fatimids gained overlordship over the Idrisids, then launched a conquest of the Maghreb. To counter the threat, the Umayyads crossed the strait to take Ceuta in 931,[122]: 171 and actively formed alliances with Berber confederacies, such as the Zenata and the Awraba. Rather than fighting each other directly, the Fatimids and Umayyads competed for Berber allegiances. In turn, this provided a motivation for the further conversion of Berbers to Islam, many of the Berbers, particularly farther south, away from the Mediterranean, being still Christian and pagan.[122]: 169–170 In turn, this would contribute to the establishment of the Almoravid dynasty and Almohad Caliphate, which would have a major impact on al-Andalus and contribute to the end of the Umayyad caliphate.[122]: 170

With the help of his new mercenary forces, Abd ar-Rahman launched a series of attacks on parts of the Iberian peninsula that had fallen away from Umayyad allegiance. In the 920s he campaigned against the areas that rebelled under Umar ibn Hafsun and refused to submit until the 920s. He conquered Mérida in 928–929, Ceuta in 931, and Toledo in 932.

Umayyad influence in western North Africa spread through diplomacy rather than conquest.

During Abd ar-Rahman's reign, tensions increased between the three distinct components of the Muslim community in al-Andalus: Berbers,

When the Fatimids moved their capital to Egypt in 969, they left north Africa in charge of viceroys from the Zirid clan of Sanhaja Berbers, who were Fatimid loyalists and enemies of the Zenata.

Considerable resentment arose in Cordoba against the increasing numbers of Berbers brought from north Africa by al-Mansur and his children Abd al-Malik and Sanchuelo.

Having abandoned Sanchuelo, the Berbers who had formed his army turned to support another ambitious Umayyad,

Al-Mahdi swore to exterminate the Berbers and pursued them. However, he was defeated in battle near Marbella. With Wadih, he fled back to Cordoba while his Catalan allies went home. The Berbers turned around and

In al-Andalus in the Taifa period

During the Taifa era, the petty kings came from a variety of ethnic groups; some—for instance the Zirid kings of Granada—were of Berber origin. The Taifa period ended when a Berber dynasty—the Moroccan Almoravids—took over al-Andalus; they were succeeded by the Almohad dynasty of Morocco, during which time al-Andalus flourished.

After the fall of Cordoba in 1013, the Saqaliba fled from the city to secure their own fiefdoms. One group of Saqaliba seized Orihuela from its Berber garrison and took control of the entire region.[122]: 201

Among the Berbers who were brought to al-Andalus by al-Mansur were the Zirid family of Sanhaja Berbers. After the fall of Cordoba, the Zirids took over Granada in 1013, forming the Zirid kingdom of Granada. The Saqaliba Khayran, with his own Umayyad figurehead Abd ar-Rahman IV al-Murtada, attempted to seize Granada from the Zirids in 1018, but failed. Khayran then executed Abd ar-Rahman IV. Khayran's son, Zuhayr, also made war on the Zirid kingdom of Granada, but was killed in 1038.[122]: 202

In Cordoba, conflicts continued between the Berber rulers and those of the citizenry who saw themselves as Arab.[122]: 202 After being installed as caliph with Berber support, Sulayman was pressured into distributing southern provinces to his Berber allies. The Sanhaja departed from Cordoba at this time. The Zenata Berber Hammudids received the important districts of Ceuta and Algeciras. The Hammudids claimed a family relation to the Idrisids, and thus traced their ancestry to the caliph Ali. In 1016 they rebelled in Ceuta, claiming to be supporting the restoration of Hisham II. They took control of Málaga, then marched on Cordoba, taking it and executing Sulayman and his family. Ali ibn Hammud al-Nasir declared himself caliph, a position he held for two years.[122]: 203

For some years, Hammudids and Umayyads fought one another and the caliphate passed between them several times. Hammudids also fought among themselves. The last Hammudid caliph reigned until 1027. The Hammudids were then expelled from Cordoba, where there was still a great deal of anti-Berber sentiment. The Hammudids remained in Málaga until expelled by the Zirids in 1056.[122]: 203 The Zirids of Granada controlled Málaga until 1073, after which separate Zirid kings retained control over the taifas of Granada and Malaga until the Almoravid conquest.[134]

During the taifa period, the Aftasid dynasty, based in Badajoz, controlled a large territory centered on the Guadiana River valley.[134] The area of Aftasid control was very large, stretching from the Sierra Morena and the taifas of Mértola and Silves in the south, to the Campo de Calatrava in the west, the Montes de Toledo in the northwest, and nearly as far as Oporto in the northeast.[134]

According to Bernard Reilly,[134]: 13 during the taifa period genealogy continued to be an obsession of the upper classes in al-Andalus. Most wanted to trace their lineage back to the Syrian and Yemeni Arabs who accompanied the invasion. In contrast, tracing descent from the Berbers who came with the same invasion "was to be stigmatized as of inferior birth".[134]: 13 Reilly notes, however, that in practice the two groups had by the 11th century become almost indistinguishable: "both groups gradually ceased to be distinguishable parts of the Muslim population, except when one of them actually ruled a taifa, in which case his low origins were well publicized by his rivals".[citation needed]

Nevertheless, distinctions between Arab, Berber, and slave were not the stuff of serious politics, either within or between the taifas. It was the individual family that was the unit of political activity."[134]: 13 The Berber that arrived towards the end of the caliphate as mercenary forces, says Reilly, amounted to only about 20 thousand people in a total al-Andalusi population of six million. Their high visibility was due to their foundation of taifa dynasties rather than large numbers.[134]: 13

In the power hierarchy, Berbers were situated between the Arabic aristocracy and the

In al-Andalus under the Almoravids

During the taifa period, the Almoravid empire developed in northwest Africa, whose core was formed by the

After their loss of Cordoba, the Hammudids had occupied Algeciras and Ceuta. In the mid-11th century, the Hammudids lost control of their Iberian possessions, but retained a small taifa kingdom based in Ceuta. In 1083, Yusuf ibn Tashufin conquered Ceuta. In the same year,

Modern history

The Kabylians were independent of outside control during the period of

The most serious

In 1902, the French penetrated the Hoggar Mountains and defeated Ahaggar Tuareg in the battle of Tit.

In 1912,

During the Algerian War (1954–1962), the FLN and ALN's reorganisation of the country created, for the first time, a unified Kabyle administrative territory, wilaya III, being as it was at the centre of the anti-colonial struggle.[143] From the moment of Algerian independence, tensions developed between Kabyle leaders and the central government.[144]

Soon after gaining independence in the middle of the twentieth century, the countries of North Africa established Arabic as their official language, replacing French, Spanish, and Italian; although the shift from European colonial languages to Arabic for official purposes continues even to this day. As a result, most Berbers had to study and know Arabic, and had no opportunities until the twenty-first century to use their mother tongue at school or university. This may have accelerated the existing process of Arabization of Berbers, especially in already bilingual areas, such as among the Chaouis of Algeria. Tamazight is now taught in Aurès since the march led by Salim Yezza in 2004.

While Berberism had its roots before the independence of these countries, it was limited to the Berber elite. It only began to succeed among the greater populace when North African states replaced their European colonial languages with Arabic and identified exclusively as Arabian nations, downplaying or ignoring the existence and the social specificity of Berbers. However, Berberism's distribution remains uneven. In response to its demands, Morocco and Algeria have both modified their policies, with Algeria redefining itself constitutionally as an "Arab, Berber, Muslim nation".

There is an identity-related debate about the persecution of Berbers by the Arab-dominated regimes of North Africa through both Pan-Arabism and Islamism,[145] their issue of identity is due to the pan-Arabist ideology of former Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Some activists have claimed that "[i]t is time—long past overdue—to confront the racist arabization of the Amazigh lands."[146]

The

In Morocco, after the constitutional reforms of 2011, Berber has become an official language, and is now taught as a compulsory language in all schools regardless of the area or the ethnicity. In 2016, Algeria followed suit and changed the status of Berber from "national" to "official" language.

Although

Arabization

The Arabization of the indigenous Berber populations was a result of the centuries-long Arab migrations to the Maghreb which began since the 7th century, in addition to changing the population's demographics. The early wave of migration prior to the 11th century contributed to the Berber adoption of Arab culture. Furthermore, the Arabic language spread during this period and drove Latin into extinction in the cities. The Arabization took place around Arab centres through the influence of Arabs in the cities and rural areas surrounding them.[149]

The migration of Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym in the 11th century had a much greater influence on the process of Arabization of the population. It played a major role in spreading Bedouin Arabic to rural areas such as the countryside and steppes, and as far as the southern areas near the Sahara.[149] It also heavily transformed the culture in the Maghreb into Arab culture, and spread nomadism in areas where agriculture was previously dominant.[150] These Bedouin tribes accelerated and deepened the Arabization process, since the Berber population was gradually assimilated by the newcomers and had to share with them pastures and seasonal migration paths. By around the 15th century, the region of modern-day Tunisia had already been almost completely Arabized.[51] As Arab nomads spread, the territories of the local Berber tribes were moved and shrank. The Zenata were pushed to the west and the Kabyles were pushed to the north. The Berbers took refuge in the mountains whereas the plains were Arabized.[151]

Currently, most Arabized Berbers identify as Berber, although the prominence of Arab influences has fully assimilated them into the Arab cultural sphere.[152]

Contemporary demographics

Ethnic groups

Ethnically, Berbers comprise a minority population in the

Prominent Berber ethnic groups include the

Outside the Maghreb, the Tuareg in Mali (early settlement near the old imperial capital of Timbuktu),[164] Niger, and Burkina Faso number some 850,000,[20] 1,620,000,[165] and 50,000, respectively. Tuaregs are a Berber ethnic group with a traditionally nomadic pastoralist lifestyle and are the principal inhabitants of the vast Sahara Desert.[166][167]

| Ethnic group | Country | Regions | Ethnic population | Linguistic population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaouis | Aurès Mountains, eastern Algeria | 2,870,000[168] | Including 2,130,000 speakers of Shawiya language[169] | |

| Chenouas | Mount Chenoua, western Algeria | 106,000[170] | Including 76,000 speakers of Shenwa language[171] | |

| Chleuhs | High Atlas, Anti-Atlas and the Sous valley, southern Morocco | 3,500,000[172] | ||

| Djerbas | Djerba, southern Tunisia | 11,000[173] | ||

| Ghomaras | Western Rif, northern Morocco | 12,000[174] | Including 10,000 speakers of Ghomara language[citation needed] | |

| Guezula | Southern Mauritania | Unknown | ||

| Kabyles | Kabylia, northern Algeria | 6,000,000[175] | Including 3,000,000 speakers of Kabyle language[176] | |

| Matmatas | Matmata, southern Tunisia | 3,700 | ||

| Mozabites | M'zab Valley, central Algeria | 200,000[177] | Including 150,000 speakers of Mozabite language[178] | |

| Nafusis | Jabal Nafusa, western Libya | 186,000[179] | Including 140,000 speakers of Nafusi language[180] | |

| Riffians | Rif, northern Morocco | 1,500,000 | Including 1,271,000 speakers of Tarifit language[181] | |

| Siwi | Siwa Oasis, western Egypt | 24,000[46] | Including 20,000 speakers of Siwi language[182] | |

| Tuareg | Sahara, northern Mali and Niger, and southern Algeria | 4,000,000 | ||

| Central Atlas Amazigh | Middle Atlas, Morocco | 2,867,000[183] | Including 2,300,000 speakers of Central Atlas Tamazight[181] | |

| Zuwaras | Zuwarah, northwestern Libya | 280,000 | 247,000 speakers of Zuwara language[184] |

Genetics

Genetically, the Berbers form the principal indigenous ancestry in the region.

The Semitic-speaking presence in the Maghreb is mainly due to the migratory movements of Phoenicians in the 3rd century BC and large scale migrations of Arab Bedouin tribes in the 11th century AD such as Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, as well as other waves that occurred during the Arab migrations to the Maghreb (c. 7th century – 17th century). The results of a study from 2017 suggest that these Arab migrations to the Maghreb were mainly a demographic process that heavily implied gene flow and remodeled the genetic structure of the Maghreb.[196]

Diaspora

According to a 2004 estimate, there were about 2.2 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians in Belgium, the Netherlands, and France; and Algerians of Kabyles and Chaouis heritage in France.[197]

Politics

Berberism

Since the 1970s,

The political outcomes have been different in each country of the Maghreb and are shaped by other factors such as geography and socioeconomic circumstances. In Algeria, the politics of the movement were focused in Kabylie, were more overtly political, and have sometimes been confrontational. In Morocco, where Amazigh populations are spread across a wider area, the movement has been less overtly political and confrontational.[55][198]: 213 In the 1990s, both states made concessions to this movement or attempted to ally itself with it, partly in response to the challenge of other political forces such as Islamism.[198]: 214

Political tensions

Over the past few decades, political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups (especially the

In contrast, many Berber students in Morocco supported Nasserism and Arabism, rather than Berberism. Many educated Berbers were attracted to the leftist National Union of Popular Forces rather than the Berber-based Popular Movement.[203]

Languages

The Berber languages form a branch of the

Tamazight is a generic name for all of the Berber languages, which consist of many closely related varieties and dialects. Among these Berber languages are Riffian, Zuwara, Kabyle, Shilha, Siwi, Zenaga, Sanhaja, Tazayit (Central Atlas Tamazight), Tumẓabt (Mozabite), Nafusi, and Tamasheq, as well as the ancient Guanche language.

Most Berber languages have a high percentage of borrowing and influence from the Arabic language, as well as from other languages.[211] For example, Arabic loanwords represent 35%[212] to 46%[213] of the total vocabulary of the Kabyle language and represent 51.7% of the total vocabulary of Tarifit.[214] The least influenced are the Tuareg languages.[211] Almost all Berber languages took from Arabic the pharyngeal fricatives /ʕ/ and /ħ/, the (nongeminated) uvular stop /q/, and the voiceless pharyngealized consonant /ṣ/.[215] In turn, Berber languages have influenced local dialects of Arabic. Although Maghrebi Arabic has a predominantly Semitic and Arabic vocabulary,[216] it contains a few Berber loanwords which represent 2–3% of the vocabulary of Libyan Arabic, 8–9% of Algerian Arabic and Tunisian Arabic, and 10–15% of Moroccan Arabic.[217]

Berber languages in total are spoken by around 14 million[162] to 16 million[163] people in Africa (see population estimation). These Berber speakers are mainly concentrated in Morocco and Algeria, followed by Mali, Niger, and Libya. Smaller Berber-speaking communities are also found as far east as Egypt, with a southwestern limit today at Burkina Faso.

Religion

The Berber identity encompasses language, religion, and ethnicity, and is rooted in the entire history and geography of North Africa. Berbers are not an entirely homogeneous ethnicity, and they include a range of societies, ancestries, and lifestyles. The unifying forces for the Berber people may be their shared language or a collective identification with Berber heritage and history.

As a legacy of the spread of Islam, the Berbers are now mostly

In antiquity, before the arrival of

Until the 1960s, there was also a significant Jewish Berber minority in Morocco,[218] but emigration (mostly to Israel and France) dramatically reduced their number to only a few hundred individuals.

Following Christian missions, the Kabyle community in Algeria has a recently constituted Christian minority, both Protestant and Roman Catholic; and a 2015 study estimates that 380,000 Muslim Algerians have converted to Christianity in Algeria.

Architecture

Antiquity

Some of the earliest evidence of original Amazigh culture in North Africa has been found in the highlands of the Sahara and dates from the second millennium BC, when the region was much less arid than it is today and when the Amazigh population was most likely in the process of spreading across North Africa.[224]: 15–22 Numerous archaeological sites associated with the Garamantes have been found in the Fezzan (in present-day Libya), attesting to the existence of small villages, towns, and tombs. At least one settlement dates from as early as 1000 BC. The structures were initially built in dry stone, but around the middle of the millennium (c. 500 BC) they began to be built with mudbrick instead.[224]: 23 By the second century AD there is evidence of large villas and more sophisticated tombs associated with the aristocracy of this society, in particular at Germa.[224]: 24

Further west, the kingdom of Numidia was contemporary with the Phoenician civilization of Carthage and the Roman Republic. Among other things, the Numidians have left thousands of pre-Christian tombs. The oldest of these is Medracen in present-day Algeria, believed to date from the time of Masinissa (202–148 BC). Possibly influenced by Greek architecture further east, or built with the help of Greek craftsmen, the tomb consists of a large tumulus constructed in well-cut ashlar masonry and featuring sixty Doric columns and an Egyptian-style cornice.[224]: 27–29 Another famous example is the Tomb of the Christian Woman in western Algeria. This structure consists of columns, a dome, and spiral pathways that lead to a single chamber.[225] A number of "tower tombs" from the Numidian period can also be found in sites from Algeria to Libya. Despite their wide geographic range, they often share a similar style: a three-story structure topped by a convex pyramid. They may have initially been inspired by Greek monuments but they constitute an original type of structure associated with Numidian culture. Examples of these are found at Siga, Soumaa d'el Khroub, Dougga, and Sabratha.[224]: 29–31

Mediterranean empires of Carthage and Rome left their mark in the material culture of North Africa as well. Phoenician and Punic (Carthaginian) remains can be found at Carthage itself and at Lixus. Numerous remains of Roman architecture can be found across the region, such as the amphitheatre of El Jem and the archaeological sites of Sabratha, Timgad, and Volubilis, among others.[226]

-

Remains of Germa, a capital of the Garamantes (first millennium BC)

-

Numidian mausoleum of Dougga, example of a "tower tomb" (2nd century BC)

After the Muslim conquest

After the

In Morocco, the largely Berber-inhabited rural valleys and oases of the Atlas and the south are marked by numerous kasbahs (fortresses) and ksour (fortified villages), typically flat-roofed structures made of rammed earth and decorated with local geometric motifs, as with the famous example of Ait Benhaddou.[227][230][231] Likewise, southern Tunisia is dotted with hilltop ksour and multi-story fortified granaries (ghorfa), such as the examples in Medenine and Ksar Ouled Soltane, which are typically built with loose stone bound by a mortar of clay.[227] Fortified granaries also exist in the Aures region of Algeria,[232] or in the form of agadirs of which numerous examples can be found in Morocco.[227][233] The island of Jerba in Tunisia, traditionally dominated by Ibadi Berbers,[234] has a traditional style of mosque architecture that consists of low-lying structures built in stone and covered in whitewash. Their prayer halls are domed and they have short, often round minarets.[234][227] The mosques are often described as "fortified mosques" because the island's flat topography made it vulnerable to attacks and as a result the mosques were designed in part to act as watch posts along the coast or in the countryside.[235][236] The M'zab region of Algeria (e.g. Ghardaïa) also has distinctive mosques and houses that are completely whitewashed, but built in rammed earth. The structures here also make frequent use of domes and barrel vaults. Unlike in Jerba, the distinctive minarets in this region are tall and have a square base, tapering towards the end and crowned with "horn"-like corners.[234][227]

-

The ksar of Aït Benhaddou in Morocco

-

Ksar Ouled Soltane, an example of a multi-level ghorfa in southern Tunisia

-

Subterranean house in Matmata (Tunisia)

-

The Fadhloun Mosque in Djerba (Tunisia), an example of a traditional "fortified mosque"

Culture and arts

Social context

The traditional social structure of the Berbers has been tribal. A leader is appointed to command the tribe. In the Middle Ages, many women had the power to govern, such as Dihya and Tazoughert Fatma in the Aurès Mountains, Tin Hinan in the Hoggar, and Chemci in Aït Iraten. Lalla Fatma N'Soumer was a Berber woman in Kabylie who fought against the French.

The majority of Berber tribes currently have men as heads of the tribe. In Algeria, the

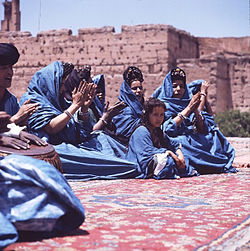

In marriages, the man usually selects the woman, and depending on the tribe, the family often makes the decision. In contrast, in the Tuareg culture, the woman chooses her future husband. The rites of marriage are different for each tribe. Families are either patriarchal or matriarchal, according to the tribe.[239]

Traditionally, men take care of

Visual arts

The Berber tribes traditionally weave

Traditional Berber jewelry is a style of jewellery, originally worn by women and girls of different rural Berber groups of Morocco, Algeria and other North African countries. It is usually made of silver and includes elaborate triangular plates and pins, originally used as clasps for garments, necklaces, bracelets, earrings and similar items. In modern times, these types of jewellery are produced also in contemporary variations and sold as a commercial product of ethnic-style fashion.[241]

From December 2004 to August 2006, the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology at Harvard University presented the exhibition Imazighen! Beauty and Artisanship in Berber Life, curated by Susan Gilson Miller and Lisa Bernasek, with an accompanying catalogue on artifacts from the Berber regions Kabylia in northeastern Algeria, the Rif mountains of northeastern Morocco and the Tuareg regions of the Algerian Sahara.[242][243]

From June to September 2007, the Musée du quai Branly in Paris showed an exhibition on the history of traditional ceramics in Algeria, titled Ideqqi, art de femmes berbères (Art of Berber women), and published an accompanying catalogue. The exhibition highlighted the originality of these pieces compared to urban earthenware, underlining their African roots as well as close relationship with the ancient art of the Mediterranean.[244]

-

Berber henna decoration

-

Detail of a traditional Berber carpet

-

Algerian Berber calendar

-

Ancient Tifinagh scripts in Algeria

-

Jewelry from Kabylia region, Algeria

Cuisine

Berber cuisine is a traditional cuisine that has evolved little over time. It differs from one area to another between and within Berber groups.

Principal Berber foods are:

- Couscous, a semolina staple dish

- Tajine, a stew made in various forms

- Pastilla, a meat pie traditionally made with squab (fledgling pigeon); today often made using chicken

- Bread made with traditional yeast

- Bouchiar, fine yeastless wafers soaked in butter and natural honey

- Bourjeje, pancake containing flour, eggs, yeast, and salt

- Baghrir, light and spongy pancake made from flour, yeast, and salt; served hot and soaked in butter and tment ('honey').

- Tahricht, sheep offal (brains, tripe, lungs, and heart) rolled up with the intestines on an oak stick and cooked on embers in specially designed ovens. The meat is coated with butter to make it even tastier. This dish is served mainly at festivities.

Although they are the original inhabitants of North Africa, and in spite of numerous incursions by Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines, Ottomans, and French, Berber groups lived in very contained communities. Having been subject to limited external influences, these populations lived free from acculturating factors.

-

Customizedtajine

-

Turkeytajine