Luis de Molina: Difference between revisions

Extended confirmed users 13,843 edits |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) (Balon Greyjoy) |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

Several regent Masters of the [[Dominican Order|Dominican]] College of St. Thomas, the future [[Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas|Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (''Angelicum'')]], were involved in the Molinist controversy. Dominicans Diego Alvarez (c.1550–1635), author of the ''De auxiliis divinae gratiae et humani arbitrii viribus'',<ref>{{cite web |

Several regent Masters of the [[Dominican Order|Dominican]] College of St. Thomas, the future [[Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas|Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (''Angelicum'')]], were involved in the Molinist controversy. Dominicans Diego Alvarez (c.1550–1635), author of the ''De auxiliis divinae gratiae et humani arbitrii viribus'',<ref>{{cite web |

||

| |

|url = http://oce.catholic.com/index.php?title=Diego_Alvarez |

||

| |

|title = Diego Alvarez |

||

| |

|work = The Original Catholic Encyclopedia |

||

| |

|date = {{date| 21 jul 2010}} |

||

| |

|accessdate = {{date| 9 mar 2013}} |

||

|deadurl = yes |

|||

|archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20120316002050/http://oce.catholic.com/index.php?title=Diego_Alvarez |

|||

|archivedate = 2012-03-16 |

|||

|df = |

|||

}}</ref> and [[Tomas de Lemos]] (1540–1629) were given the responsibility of representing the [[Dominican Order]] in debates before [[Pope Clement VIII]] and [[Pope Paul V]].<ref>{{cite web |

}}</ref> and [[Tomas de Lemos]] (1540–1629) were given the responsibility of representing the [[Dominican Order]] in debates before [[Pope Clement VIII]] and [[Pope Paul V]].<ref>{{cite web |

||

| work = Enciclopedia Treccani |

| work = Enciclopedia Treccani |

||

| Line 56: | Line 60: | ||

*[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10436a.htm Article on Molina] from ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (1911) |

*[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10436a.htm Article on Molina] from ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (1911) |

||

*[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10437a.htm Article on Molinism] from ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (1911) |

*[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10437a.htm Article on Molinism] from ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (1911) |

||

* Ulrich L. Lehner (ed.), ''Die scholastische Theologie im Zeitalter der Gnadenstreitigkeiten'' (monograph series, first volume: 2007) http://www.bautz.de/rfn.html |

* Ulrich L. Lehner (ed.), ''Die scholastische Theologie im Zeitalter der Gnadenstreitigkeiten'' (monograph series, first volume: 2007) https://web.archive.org/web/20070812004619/http://www.bautz.de/rfn.html |

||

* Luis de Molina, ''[http://www.clpress.com/publications/treatise-money A Treatise on Money]''. CLP Academic, 2015. |

* Luis de Molina, ''[http://www.clpress.com/publications/treatise-money A Treatise on Money]''. CLP Academic, 2015. |

||

Revision as of 20:40, 3 December 2017

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2014) |

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

|

Luis de Molina (September 1535,

Life

From 1551 to 1562, Molina studied law in Salamanca, philosophy in Alcala de Henares, and theology in Coimbra. After 1563, he became a professor at the University of Coimbra, and afterward taught at the University of Évora, Portugal. From this post he was called, at the end of twenty years, to the chair of moral theology in Madrid, where he died.[1]

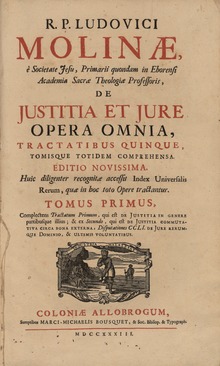

Besides other works he wrote De liberi arbitrii cum gratiae donis, divina praescientia, praedestinatione et reprobatione concordia (4 vo., Lisbon, 1588); a commentary on the first part of the Summa Theologiae of Thomas Aquinas (2 vols., fol., Cuenca, 1593); and a treatise De jure et justitia (6 vols., 1593–1609).

It is to the first of these that his fame is principally due. It was an attempt to reconcile, in words at least, the

These doctrines, which opposed both traditional understanding of

Several regent Masters of the Dominican College of St. Thomas, the future Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum), were involved in the Molinist controversy. Dominicans Diego Alvarez (c.1550–1635), author of the De auxiliis divinae gratiae et humani arbitrii viribus,[2] and Tomas de Lemos (1540–1629) were given the responsibility of representing the Dominican Order in debates before Pope Clement VIII and Pope Paul V.[3]

The Molinist subsequently passed into the

Molina was also the first Jesuit to write at length on

See also

Bibliography

A full account of Molina's theology will be found in

- Ernest Renan's article, Les congregations de auxiliis in his Nouvelles études d'histoire religieuse.

- Alonso-Lasheras, Diego. "Luis de Molina's De Iustitia et Iure. Justice as Virtue in an Economic Context", Leiden: Brill 2011.

- Matthias Kaufmann, Alexander Aichele (eds.), A Companion to Luis de Molina, Leiden: Brill 2014.

- MacGregor, Kirk. Luis de Molina: The Life and Theology of the Founder of Middle Knowledge. Grand Rapids: Zondervan 2015. [the first full book on Molina]

- Smith, Gerard (ed.) Jesuit thinkers of the Renaissance, Milwaukee (USA) 1939, pp. 75–132.

- A critical edition of Treatise on Money was translated and published by Christian's Library Press as A Treatise on Money (2015).[7]

Notes

- ^ Luis de Molina, A Treatise on Money. CLP Academic, 2015, p.xxiii.

- ^ "Diego Alvarez". The Original Catholic Encyclopedia. 21 July 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lemos "lé-", Tomás de". Enciclopedia Treccani (in Italian). Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Luis de Molina, A Treatise on Money. CLP Academic, 2015, p.xxv.

- ^ Luis de Molina A Treatise on Money. CLP Academic, 2015, p.xxvi.

- ^ Luis de Molina, A Treatise on Money. CLP Academic, 2015, p.96.

- ^ Luis de Molina, A Treatise on Money. CLP Academic, 2015.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Molina, Luis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 667.

- An article by Alfred J. Freddoso on Luis Molina's thoughts.

- Article on Molina from Catholic Encyclopedia (1911)

- Article on Molinism from Catholic Encyclopedia (1911)

- Ulrich L. Lehner (ed.), Die scholastische Theologie im Zeitalter der Gnadenstreitigkeiten (monograph series, first volume: 2007) https://web.archive.org/web/20070812004619/http://www.bautz.de/rfn.html

- Luis de Molina, A Treatise on Money. CLP Academic, 2015.