Taxonomic rank

In

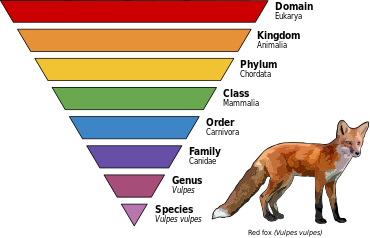

A given rank subsumes less general categories under it, that is, more specific descriptions of life forms. Above it, each rank is classified within more general categories of organisms and groups of organisms related to each other through inheritance of traits or features from common ancestors. The rank of any species and the description of its genus is basic; which means that to identify a particular organism, it is usually not necessary to specify ranks other than these first two.[1]

Consider a particular species, the

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature defines rank as: "The level, for nomenclatural purposes, of a taxon in a taxonomic hierarchy (e.g. all families are for nomenclatural purposes at the same rank, which lies between superfamily and subfamily)."[2]

Main ranks

In his landmark publications, such as the

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| regio | domain |

| regnum | kingdom |

| phylum | phylum (in zoology) / division (in botany) |

| classis | class |

| ordo | order |

| familia | family |

| genus | genus |

| species | species |

A taxon is usually assigned a rank when it is given its formal name. The basic ranks are species and genus. When an organism is given a species name it is assigned to a genus, and the genus name is part of the species name.

The species name is also called a binomial, that is, a two-term name. For example, the zoological name for the human species is Homo sapiens. This is usually italicized in print or underlined when italics are not available. In this case, Homo is the generic name and it is capitalized; sapiens indicates the species and it is not capitalized.

Ranks in zoology

There are definitions of the following taxonomic ranks in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature: superfamily, family, subfamily, tribe, subtribe, genus, subgenus, species, subspecies.[5]

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature divides names into "family-group names", "genus-group names" and "species-group names". The Code explicitly mentions the following ranks for these categories:[5]: §29–31

- Family-groups

- Genus-groups

- Species-groups

The rules in the Code apply to the ranks of superfamily to subspecies, and only to some extent to those above the rank of superfamily. Among "genus-group names" and "species-group names" no further ranks are officially allowed. Zoologists sometimes use additional terms such as species group, species subgroup, species complex and superspecies for convenience as extra, but unofficial, ranks between the subgenus and species levels in

At higher ranks (family and above) a lower level may be denoted by adding the prefix "infra", meaning lower, to the rank. For example, infraorder (below suborder) or infrafamily (below subfamily).

Names of zoological taxa

- A taxon above the rank of species has a scientific name in one part (a uninominal name).

- A species has a name composed of two parts (a binomial name or generic name + specific name; for example Canis lupus.

- A subspecies has a name composed of three parts (a trinomial name or trinomen): generic name + specific name + subspecific name; for example Canis lupus italicus. As there is only one possible rank below that of species, no connecting term to indicate rank is needed or used.

Ranks in botany

According to Art 3.1 of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) the most important ranks of taxa are: kingdom, division or phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. According to Art 4.1 the secondary ranks of taxa are tribe, section, series, variety and form. There is an indeterminate number of ranks. The ICN explicitly mentions:[6]: Articles 3 and 4

| Rank | Type | Suffix |

|---|---|---|

| kingdom (regnum) | primary | — |

| subregnum | further | — |

| division (divisio) phylum (phylum) |

primary | ‑phyta -mycota (fungi) |

| subdivisio or subphylum | further | ‑phytina -mycotina (fungi) |

| class (classis) | primary | ‑opsida (plant) ‑phyceae (algae) -mycetes (fungi) |

| subclassis | further | ‑idae (plant) ‑phycidae (algae) -mycetidae (fungi) |

| order (ordo) | primary | -ales |

| subordo | further | -ineae |

| family (familia) | primary | -aceae |

| subfamilia | further | ‑oideae |

| tribe (tribus) | secondary | -eae |

| subtribus | further | ‑inae |

| genus (genus) | primary | — |

| subgenus | further | — |

| section (sectio) | secondary | — |

| subsectio | further | — |

| series (series) | secondary | — |

| subseries | further | — |

| species (species) | primary | — |

| subspecies | further | — |

| variety (varietas) | secondary | — |

| subvarietas | further | — |

| form (forma) | secondary | — |

| subforma | further | — |

There are definitions of the following taxonomic categories in the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants: cultivar group, cultivar, grex.

The rules in the ICN apply primarily to the ranks of family and below, and only to some extent to those above the rank of family.

Names of botanical taxa

Taxa at the rank of genus and above have a

Hybrids can be specified either by a "hybrid formula" that specifies the parentage, or may be given a name. For hybrids receiving a

Outdated names for botanical ranks

If a different term for the rank was used in an old publication, but the intention is clear, botanical nomenclature specifies certain substitutions:[citation needed]

- If names were "intended as names of orders, but published with their rank denoted by a term such as": "cohors" [Latin for "cohort";[9] see also cohort study for the use of the term in ecology], "nixus", "alliance", or "Reihe" instead of "order" (Article 17.2), they are treated as names of orders.

- "Family" is substituted for "order" (ordo) or "natural order" (ordo naturalis) under certain conditions where the modern meaning of "order" was not intended. (Article 18.2)

- "Subfamily is substituted for "suborder" (subordo) under certain conditions where the modern meaning of "suborder" was not intended. (Article 19.2)

- In a publication prior to 1 January 1890, if only one infraspecific rank is used, it is considered to be that of variety. (Article 37.4) This commonly applies to publications that labelled infraspecific taxa with Greek letters, α, β, γ, ...

Examples

Classifications of five species follow: the fruit fly familiar in genetics laboratories (Drosophila melanogaster), humans (Homo sapiens), the peas used by Gregor Mendel in his discovery of genetics (Pisum sativum), the "fly agaric" mushroom Amanita muscaria, and the bacterium Escherichia coli. The eight major ranks are given in bold; a selection of minor ranks are given as well.

| Rank | Fruit fly | Human | Pea | Fly agaric | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Bacteria |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animalia | Plantae | Fungi | |

| Phylum or division | Arthropoda | Chordata | Tracheophyta )

|

Basidiomycota | Pseudomonadota |

| Subphylum or subdivision | Hexapoda | Vertebrata | Magnoliophytina ( Euphyllophytina )

|

Agaricomycotina | |

| Class | Insecta | Mammalia | Equisetopsida )

|

Agaricomycetes | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Subclass | Pterygota | Theria | Rosidae (Magnoliidae) | Agaricomycetidae | |

| Superorder | Panorpida | Euarchontoglires | Rosanae | ||

| Order | Diptera | Primates | Fabales | Agaricales | Enterobacterales |

| Suborder | Brachycera | Haplorrhini

|

Fabineae | Agaricineae | |

| Family | Drosophilidae | Hominidae

|

Fabaceae | Amanitaceae | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Subfamily | Drosophilinae | Homininae | Faboideae | Amanitoideae | |

| Tribe | Drosophilini | Hominini | Fabeae | ||

| Genus | Drosophila | Homo | Pisum

|

Amanita | Escherichia |

| Species | D. melanogaster | H. sapiens | P. sativum | A. muscaria | E. coli |

- Table notes

- In order to keep the table compact and avoid disputed technicalities, some common and uncommon intermediate ranks are omitted. For example, the – but only Mammalia and Theria are in the table. Legitimate arguments might arise if the commonly used clades Eutheria and Placentalia were both included, over which is the rank "infraclass" and what the other's rank should be, or whether the two names are synonyms.

- The ranks of higher taxa, especially intermediate ranks, are prone to revision as new information about relationships is discovered. For example, the flowering plants have been downgraded from a division (Magnoliophyta) to a subclass (Magnoliidae), and the superorder has become the rank that distinguishes the major groups of flowering plants.[10] The traditional classification of primates (class Mammalia, subclass Theria, infraclass Eutheria, order Primates) has been modified by new classifications such as McKenna and Bell (class Mammalia, subclass Theriformes, infraclass Holotheria) with Theria and Eutheria assigned lower ranks between infraclass and the order Primates. These differences arise because there are few available ranks and many branching points in the fossil record.

- Within species further units may be recognised. Animals may be classified into subspecies (for example, Homo sapiens sapiens, modern humans) or morphs (for example Corvus corax varius morpha leucophaeus, the pied raven). Plants may be classified into subspecies (for example, Pisum sativum subsp. sativum, the garden pea) or varieties (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon, snow pea), with cultivated plants getting a cultivar name (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon 'Snowbird'). Bacteria may be classified by strains (for example Escherichia coli O157:H7, a strain that can cause food poisoning).

Terminations of names

Pronunciations given are the most Anglicized. More Latinate pronunciations are also common, particularly /ɑː/ rather than /eɪ/ for stressed a.

| Rank | Bacteria and Archaea[11] | Embryophytes (Plants) | Algae (Diaphoretickes) | Fungi | Animals | Viruses[12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Realm | -viria | |||||

| Subrealm | -vira | |||||

| Kingdom | -virae | |||||

| Subkingdom | -viretes | |||||

| Division/phylum | -ota[13] | -ophyta[14] /ˈɒfətə, ə(ˈ)faɪtə/ | -mycota /maɪˈkoʊtə/ | -viricota /vɪrəˈkoʊtə/ | ||

| Subdivision/subphylum | -phytina[14] /fəˈtaɪnə/ | -mycotina /maɪkəˈtaɪnə/ | -viricotina /vɪrəkəˈtaɪnə/ | |||

| Class | -ia /iə/ | -opsida /ˈɒpsədə/ | -phyceae /ˈfaɪʃiː/ | -mycetes /maɪˈsiːtiːz/ | -viricetes /vɪrəˈsiːtiːz/ | |

| Subclass | -idae /ədiː/ | -phycidae /ˈfɪsədiː/ | -mycetidae /maɪˈsɛtədiː/ | -viricetidae /vɪrəˈsɛtədiː/ | ||

| Superorder | -anae /ˈeɪniː/ | |||||

| Order | -ales /ˈeɪliːz/ | -ida /ədə/ or -iformes /ə(ˈ)fɔːrmiːz/ | -virales /vaɪˈreɪliːz/ | |||

| Suborder | -ineae /ˈɪniːiː/ | -virineae /vəˈrɪniːiː/ | ||||

| Infraorder | -aria /ˈɛəriə/ | |||||

| Superfamily | -acea /ˈeɪʃə/ | -oidea /ˈɔɪdiːə/ | ||||

| Epifamily | -oidae /ˈɔɪdiː/ | |||||

| Family | -aceae /ˈeɪʃiː/ | -idae /ədiː/ | -viridae /ˈvɪrədiː/ | |||

| Subfamily | -oideae /ˈɔɪdiːiː/ | -inae /ˈaɪniː/ | -virineae /vɪˈrɪniːiː/ | |||

| Infrafamily | -odd /ɒd/[15] | |||||

| Tribe | -eae /iːiː/ | -ini /ˈaɪnaɪ/ | ||||

| Subtribe | -inae /ˈaɪniː/ | -ina /ˈaɪnə/ | ||||

| Infratribe | -ad /æd/ or -iti /ˈaɪti/ | |||||

| Genus | -virus | |||||

| Subgenus | -virus | |||||

- Table notes

- In botany and mycology names at the rank of family and below are based on the name of a genus, sometimes called the type genus of that taxon, with a standard ending. For example, the rose family, Rosaceae, is named after the genus Rosa, with the standard ending "-aceae" for a family. Names above the rank of family are also formed from a generic name, or are descriptive (like Gymnospermae or Fungi).

- For animals, there are standard suffixes for taxa only up to the rank of superfamily.[16] Uniform suffix has been suggested (but not recommended) in AAAS[17] as -ida /ɪdə/ for orders, for example; protozoologists seem to adopt this system. Many metazoan (higher animals) orders also have such suffix, e.g. Hyolithida and Nectaspida (Naraoiida).

- Forming a name based on a generic name may be not straightforward. For example, the homo has the genitive hominis, thus the genus Homo (human) is in the Hominidae, not "Homidae".

- The ranks of epifamily, infrafamily and infratribe (in animals) are used where the complexities of phyletic branching require finer-than-usual distinctions. Although they fall below the rank of superfamily, they are not regulated under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and hence do not have formal standard endings. The suffixes listed here are regular, but informal.[18]

- In virology, the formal endings for taxa of

All ranks

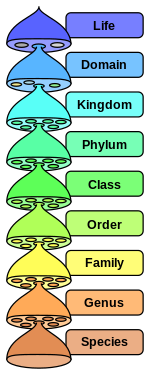

There is an indeterminate number of ranks, as a taxonomist may invent a new rank at will, at any time, if they feel this is necessary. In doing so, there are some restrictions, which will vary with the nomenclature code which applies.[citation needed]

The following is an artificial synthesis, solely for purposes of demonstration of relative rank (but see notes), from most general to most specific:[19]

- Superdomain

- Domain or Empire

- Subdomain (biology)

- Domain or Empire

- Realm (in virology)[12]

- Subrealm (in virology)[12]

- Hyperkingdom

- Superkingdom

- Kingdom

- Subkingdom

- Infrakingdom

- Parvkingdom

- Infrakingdom

- Kingdom

- Superphylum, or superdivision (in botany)

- Superclass

- Superdivision (in zoology)[20]

- Superlegion (in zoology)

- Legion (in zoology)

- Sublegion (in zoology)

- Infralegion (in zoology)

- Sublegion (in zoology)

- Legion (in zoology)

- Supercohort (in zoology)[21]

- Gigaorder (in zoology)[22]

- Section (in zoology)

- Subsection (in zoology)

- Gigafamily (in zoology)

- Supertribe

- Supergenus

- Species complex

- Species

- Subspecies, or forma specialis (for fungi), or pathovar (for bacteria)[23])

- morph (in zoology) or aberration(in lepidopterology)

- Subvariety (in botany)

- Form or forma (in botany)

- Subvariety (in botany)

- Subspecies, or forma specialis (for fungi), or pathovar (for bacteria)[23])

- Species

Significance and problems

Ranks are assigned based on subjective dissimilarity, and do not fully reflect the gradational nature of variation within nature. In most cases, higher taxonomic groupings arise further back in time: not because the rate of diversification was higher in the past, but because each subsequent diversification event results in an increase of diversity and thus increases the taxonomic rank assigned by present-day taxonomists.[24] Furthermore, some groups have many described species not because they are more diverse than other species, but because they are more easily sampled and studied than other groups.[citation needed]

Of these many ranks, the most basic is species. However, this is not to say that a taxon at any other rank may not be sharply defined, or that any species is guaranteed to be sharply defined. It varies from case to case. Ideally, a taxon is intended to represent a clade, that is, the phylogeny of the organisms under discussion, but this is not a requirement.[citation needed]

A classification in which all taxa have formal ranks cannot adequately reflect knowledge about phylogeny. Since taxon names are dependent on ranks in traditional Linnaean systems of classification, taxa without ranks cannot be given names. Alternative approaches, such as using circumscriptional names, avoid this problem.[25][26] The theoretical difficulty with superimposing taxonomic ranks over evolutionary trees is manifested as the boundary paradox which may be illustrated by Darwinian evolutionary models.

There are no rules for how many species should make a genus, a family, or any other higher taxon (that is, a taxon in a category above the species level).

Mnemonic

There are several acronyms intended to help memorise the taxonomic hierarchy, such as "King Phillip came over for great spaghetti".[29]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ The Virginia opossum is an exception.

References

- ^ "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants – Melbourne Code". IAPT-Taxon.org. 2012. Articles 2 and 3. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1999), International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Fourth Edition, International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, archived from the original on 21 May 2019, retrieved 12 April 2015

- (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Luketa, S. (2012). "New views on the megaclassification of life" (PDF). Protistology. 7 (4): 218–237. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- ^ ISBN 0 85301 006 4. Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ a b "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants – Melbourne Code". IAPT-Taxon.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants – Melbourne Code". IAPT-Taxon.org. 2012. Articles 4.2 and 24.1. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants – Melbourne Code". IAPT-Taxon.org. 2012. Article 3.2, and Appendix 1, Articles H.1–3. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Stearn, W.T. 1992. Botanical Latin: History, grammar, syntax, terminology and vocabulary, Fourth edition. David and Charles.

- .

- ^ a b c d e "ICTV Code. Section 3.IV, § 3.23; section 3.V, §§ 3.27-3.28." International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ISSN 1466-5034.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ a b "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code)". IAPT-Taxon.org. 2018. Article 16. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- chelonianinfrafamilies Chelodd (Gaffney & Meylan 1988: 169) and Baenodd (ibid., 176).

- ^ ICZN article 29.2

- ^ Pearse, A.S. (1936) Zoological names. A list of phyla, classes, and orders, prepared for section F, American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived 15 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine American Association for the Advancement of Science, p. 4

- ^ As supplied by Gaffney & Meylan (1988).

- ^ For the general usage and coordination of zoological ranks between the phylum and family levels, including many intercalary ranks, see Carroll (1988). For additional intercalary ranks in zoology, see especially Gaffney & Meylan (1988); McKenna & Bell (1997); Milner (1988); Novacek (1986, cit. in Carroll 1988: 499, 629); and Paul Sereno's 1986 classification of ornithischian dinosaurs as reported in Lambert (1990: 149, 159). For botanical ranks, including many intercalary ranks, see Willis & McElwain (2002).

- ^ a b c d These are movable ranks, most often inserted between the class and the legion or cohort. Nevertheless, their positioning in the zoological hierarchy may be subject to wide variation. For examples, see the Benton classification of vertebrates Archived 16 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine (2005).

- ^ a b c d In zoological classification, the cohort and its associated group of ranks are inserted between the class group and the ordinal group. The cohort has also been used between infraorder and family in saurischian dinosaurs (Benton Archived 16 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine 2005). In botanical classification, the cohort group has sometimes been inserted between the division (phylum) group and the class group: see Willis & McElwain (2002: 100–101), or has sometimes been used at the rank of order, and is now considered to be an obsolete name for order: See International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, Melbourne Code 2012, Article 17.2.

- ^ a b c d e The supra-ordinal sequence gigaorder–megaorder–capaxorder–hyperorder (and the microorder, in roughly the position most often assigned to the parvorder) has been employed in turtles at least (Gaffney & Meylan 1988), while the parallel sequence magnorder–grandorder–mirorder figures in recently influential classifications of mammals. It is unclear from the sources how these two sequences are to be coordinated (or interwoven) within a unitary zoological hierarchy of ranks. Previously, Novacek (1986) and McKenna-Bell (1997) had inserted mirorders and grandorders between the order and superorder, but Benton (2005) now positions both of these ranks above the superorder.

- serovar designate bacterial strains(genetic variants) that are physiologically or biochemically distinctive. These are not taxonomic ranks, but are groupings of various sorts which may define a bacterial subspecies.

- doi:10.1139/z87-169.

- ^ Kluge, N.J. (1999). "A system of alternative nomenclatures of supra-species taxa. Linnaean and post-Linnaean principles of systematics". Entomological Review. 79 (2): 133–147.

- .

- ^ Stuessy, T.F. (2009). Plant Taxonomy: The Systematic Evaluation of Comparative Data. 2nd ed. Columbia University Press, p. 175.

- ^ a b Brusca, R.C. & Brusca, G.J. (2003). Invertebrates. 2nd ed. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, pp. 26–27.

- ISBN 978-1-4406-2207-6. Archivedfrom the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

Bibliography

- JSTOR 2481265.

- ISBN 9780632056378.

- Brummitt, R. K.; Powell, C. E. (1992). ISBN 0947643443.

- ISBN 0716718227.

- Gaffney, Eugene S.; Meylan, Peter A. (1988). "A phylogeny of turtles". In Benton, M. J. (ed.). The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods. Vol. 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 157–219.

- Lambert, David (1990). Dinosaur Data Book. Oxford: Facts on File / British Museum (Natural History. ISBN 0816024316.

- McKenna, Malcolm C.; Bell, Susan K., eds. (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231110138.

- Milner, Andrew (1988). "The relationships and origin of living amphibians". In Benton, M. J. (ed.). The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods. Vol. 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 59–102.

- Novacek, Michael J. (1986). "The skull of leptictid insectivorans and the higher-level classification of eutherian mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (183): 1–112.

- Sereno, Paul C. (1986). "Phylogeny of the bird-hipped dinosaurs (Order Ornithischia)". National Geographic Research. 2: 234–256.

- Willis, K. J.; McElwain, J. C. (2002). The Evolution of Plants. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198500653.