Science and technology of the Song dynasty

| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

The

The ingenuity of advanced

Notable advances in

Polymaths and mechanical engineering

Polymaths

Su Song, one of Shen Kuo's political rivals at court, wrote a famous

Intellectual men of letters like the versatile Shen Kuo dabbled in subjects as diverse as mathematics, geography, geology, economics, engineering, medicine, art criticism, archaeology, military strategy, and diplomacy, among others.[20][21] On a court mission to inspect a frontier region, Shen Kuo once made a raised-relief map of wood and glue-soaked sawdust to show the mountains, roads, rivers, and passes to other officials.[20] He once computed the total number of possible situations on a game board, another time the longest possible military campaign given the limits of human carriers who would bring their own food and food for other soldiers.[20] Shen Kuo is also noted for improving the designs of the inflow clepsydra clock for a more efficient higher-order interpolation, the armillary sphere, the gnomon, and the astronomical sighting tube; increasing its width for better observation of the pole star and other celestial bodies.[22] Shen Kuo also experimented with camera obscura, only a few decades after the first to do so, Ibn al-Haytham (965–1039).[23]

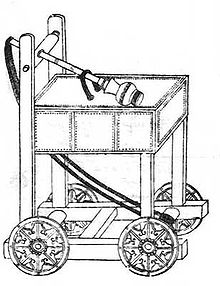

Odometer and south-pointing chariot

There were many other important figures in the Song era besides Shen Kuo and Su Song, many of whom contributed greatly to the technological innovations of the time period. Although the mechanically driven mile-marking device of the carriage-drawn odometer had been known in China since the ancient Han dynasty, the Song Shi (compiled in 1345) provides a much greater description and more in-depth view of the device than earlier Chinese sources. The Song Shi states:

The odometer. [The mile-measuring carriage] is painted red, with pictures of flowers and birds on the four sides, and constructed in two storeys, handsomely adorned with carvings. At the completion of every li, the wooden figure of a man in the lower storey strikes a drum; at the completion of every ten li, the wooden figure in the upper storey strikes a bell. The carriage-pole ends in a phoenix-head, and the carriage is drawn by four horses. The escort was formerly of 18 men, but in the 4th year of the Yongxi reign period (987) the emperor Taizong increased it to 30. In the 5th year of the Tian-Sheng reign-period (1027) the Chief Chamberlain Lu Daolong presented specifications for the construction of odometers as follows: [...][24]

What follows is a long dissertation made by the Chief Chamberlain Lu Daolong on the ranging measurements and sizes of wheels and gears.[24] However, the concluding paragraph provides description at the end of how the device ultimately functions:

When the middle horizontal wheel has made 1 revolution, the carriage will have gone 1 li and the wooden figure in the lower story will strike the drum. When the upper horizontal wheel has made 1 revolution, the carriage will have gone 10 li and the figure in the upper storey will strike the bell. The number of wheels used, great and small, is 8 inches (200 mm) in all, with a total of 285 teeth. Thus the motion is transmitted as if by the links of a chain, the "dog-teeth" mutually engaging with each other, so that by due revolution everything comes back to its original starting point.[25]

In the Song period (and once during the earlier Tang period), the odometer device was combined with the

In the first year of the Da-Guan reign period (1107), the Chamberlain Wu Deren presented specifications of the south-pointing carriage and the carriage with the li-recording drum (odometer). The two vehicles were made, and were first used that year at the great ceremony of the ancestral sacrifice.[27]

The text then went on to describe in full detail the intricate mechanical design for the two devices combined into one. (See the article on the south-pointing chariot).

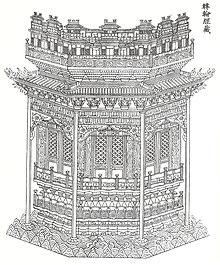

Revolving repositories

Besides clockwork, hydraulic-powered armillary spheres, odometers, and mechanical compass vehicles, there were other impressive devices of mechanical engineering found during the Song dynasty. Although literary references for mechanical revolving repositories and book cases of Buddhist temples trace back to at least 823 during the Tang dynasty,[28] they came to prominence during the Song dynasty.[28] The invention of the revolving book case is considered to have happened earlier, and is credited to the layman Fu Xi in 544.[29] Revolving bookcases were popularized in Buddhist monasteries during the Song dynasty under the reign of Emperor Taizu, who ordered the mass printing of the Buddhist Tripiṭaka scriptures.[29] Furthermore, the oldest surviving rotating book case dates to the Song period (12th century), found at the

In another temple there is an octagonal kiosque, having from the top to the bottom fifteen stories. Each story contains apartments decorated with

verandahs...It is entirely made of polished wood, and this again gilded so admirably that it seems to be of solid gold. There is a vault below it. An iron shaft fixed in the center of the kiosque traverses it from bottom to top, and the lower end of this works in an iron plate, whilst the upper end bears on strong supports in the roof of the edifice which contains this pavilion. Thus a person in the vault can with a trifling exertion cause this great kiosque to revolve. All the carpenters, smiths, and painters in the world would learn something in their trades by coming here![33]

Textile machinery

In the field of manufacturing

The pulley (bearing the eccentric lug) is provided with a groove for the reception of the driving belt, an endless band which responds to the movement of the machine by continuously rotating the pulley.[35]

An endless rope or cord may have been used in

Movable type printing

For printing, the mass production of

Gunpowder warfare

Flamethrower

Advances in military technology aided the

Fire lance

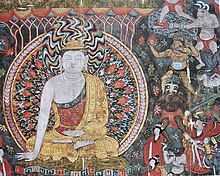

Although the destructive effects of gunpowder were described in the earlier Tang dynasty by a Daoist alchemist, the earliest-known existent written formulas for gunpowder come from the Wujing Zongyao text of 1044, which described explosive bombs hurled from catapults.[52] The earliest developments of the gun barrel and the projectile-fire cannon were found in late Song China. The first art depiction of the Chinese 'fire lance' (a combination of a temporary-fire flamethrower and gun) was from a Buddhist mural painting of Dunhuang, dated circa 950.[53] These 'fire-lances' were widespread in use by the early 12th century, featuring hollowed bamboo poles as tubes to fire sand particles (to blind and choke), lead pellets, bits of sharp metal and pottery shards, and finally large gunpowder-propelled arrows and rocket weaponry.[54] Eventually, perishable bamboo was replaced with hollow tubes of cast iron, and so too did the terminology of this new weapon change, from 'fire-spear' ('huo qiang') to 'fire-tube' ('huo tong').[55] This ancestor to the gun was complemented by the ancestor to the cannon, what the Chinese referred to since the 13th century as the 'multiple bullets magazine erupter' ('bai zu lian zhu pao'), a tube of bronze or cast iron that was filled with about 100 lead balls.[56] In 1132, at the siege of De'an, Song Chinese forces used fire lances against the rival Jurchen-led Jin dynasty.[57]

Gun

An early known depiction of a gun is a sculpture from a cave in

The shells are made of cast iron, as large as a bowl and shaped like a ball. Inside they contain half a pound of 'magic' gunpowder. They are sent flying towards the enemy camp from an eruptor; and when they get there a sound like a thunder-clap is heard, and flashes of light appear. If ten of these shells are fired successfully into the enemy camp, the whole place will be set ablaze...[60]

As noted before, the change in terminology for these new weapons during the Song period were gradual. The early Song cannons were at first termed the same way as the Chinese

The Song people used the turntable trebuchet, the single-pole trebuchet and the

squatting-tiger trebuchet. They were all called 'fire trebuchets' because they were used to project fire-weapons like the (fire-)ball, (fire-)falcon, and (fire-)lance. They were the ancestors of the cannon.[61]

Land mine

The 14th century Huolongjing was also one of the first Chinese texts to carefully describe to the use of explosive land mines, which had been used by the late Song Chinese against the Mongols in 1277, and employed by the Yuan dynasty afterwards.[62] The innovation of the detonated land mine was accredited to one Luo Qianxia in the campaign of defense against the Mongol invasion by Kublai Khan,[62] Later Chinese texts revealed that the Chinese land mine employed either a rip cord or a motion booby trap of a pin releasing falling weights that rotated a steel flint wheel, which in turn created sparks that ignited the train of fuses for the land mines.[63]

Rocket

Furthermore, the Song employed the earliest known gunpowder-propelled rockets in warfare during the late 13th century,[64] its earliest form being the archaic fire arrow. When the Northern Song capital of Kaifeng fell to the Jurchens in 1126, it was written by Xia Shaozeng that 20,000 fire arrows were handed over to the Jurchens in their conquest.[65] An even earlier Chinese text of the Wujing Zongyao ("Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques"), written in 1044 by the Song scholars Zeng Kongliang and Yang Weide, described the use of three spring or triple bow arcuballista that fired arrow bolts holding gunpowder packets near the head of the arrow.[65] Going back yet even farther, the Wu Li Xiao Shi (1630, second edition 1664) of Fang Yizhi stated that fire arrows were presented to Emperor Taizu of Song (r. 960–976) in 960.[66]

Civil engineering

In ancient China, the

Qiao Weiyue also built five double slipways (lit. dams) between Anbei and Huaishi (or, the quays on the Huai waterfront). Each of these had ten lanes for the barges to go up and down. Their cargoes of imperial tax-grain were heavy, and as they were passing over they often came to grief and were damaged or wrecked, with loss of the grain and peculation by a cabal of the workers in league with local bandits hidden nearby. Qiao Weiyue therefore first ordered the construction of two gates at the third dam along the West River (near Huaiyin). The distance between the two gates was rather more than 50 paces (250 ft) and the whole space was covered over with a great roof like a shed. The gates were 'hanging gates'; (when they were closed) the water accumulated like a tide until the required level was reached, and then when the time came it was allowed to flow out. He also built a horizontal bridge to protect their foundations. After this was done (to all the double slipways) the previous corruption was completely eliminated, and the passage of the boats went on without the slightest impediment.[69]

This practice became widespread, and was even written of by the Chinese polymath scientist Shen Kuo in his (1037–1101), who wrote about two decades before Shen Kuo in 1060:

Several years ago the government built sluice gates for the silt fertilization method, though many people disagreed with the plan. In spite of all opposition it was carried through, yet it had little success. When the torrents on Fan Shan were abundant, the gates were kept closed, and this caused damage (by flooding) of fields, tombs, and houses. When the torrents subsided in the late autumn the sluices were opened, and thus the fields were irrigated with silt-bearing water, but the deposit was not as thick as what the peasants call 'steamed cake silt' (so they were not satisfied). Finally the government got tired of it and stopped. In this connection I remember reading the Jiayipan of Bai Juyi (the poet) in which he says that he once had a position as Traffic Commissioner. As the Bian River was getting so shallow that it hindered the passage of boats he suggested that the sluice gates along the river and canal should be closed, but the Military Governor pointed out that the river was bordered on both sides by fields which supplied army grain, and if these were denied irrigation (water and silt) because of the closing of the sluice gates, it would lead to shortages in army grain supplies. From this I learnt that in the Tang period there were government fields and sluice gates on both sides of the river, and that irrigation was carried on (continuously) even when the water was high. If this could be done (successfully) in old times, why can it not be done now? I should like to enquire further about the matter from experts.[73]

Although the

At the beginning of the dynasty (c. 965) the two Zhe provinces (now Zhejiang and southern Jiangsu) presented (to the throne) two dragon ships each more than (60.00 m/200 ft) in length.[74] The upper works included several decks with palatial cabins and saloons, containing thrones and couches all ready for imperial tours of inspection. After many years, their hulls decayed and needed repairs, but the work was impossible as long as they were afloat. So in the Xi-Ning reign period (1068 to 1077) a palace official Huang Huaixin suggested a plan. A large basin was excavated at the north end of the Jinming Lake capable of containing the dragon ships, and in it heavy crosswise beams were laid down upon a foundation of pillars. Then (a breach was made) so that the basin quickly filled with water, after which the ships were towed in above the beams. The (breach now being closed) the water was pumped out by wheels so that the ships rested quite in the air. When the repairs were complete, the water was let in again, so that the ships were afloat once more (and could leave the dock). Finally the beams and pillars were taken away, and the whole basin covered over with a great roof so as to form a hangar in which the ships could be protected from the elements and avoid the damage caused by undue exposure.[75]

Nautics

Background

The Chinese of the Song dynasty were adept sailors who traveled to ports of call as far away as Fatimid Egypt. They were well equipped for their journeys abroad, in large seagoing vessels steered by stern-post rudders and guided by the directional compass. Even before Shen Kuo and Zhu Yu had described the mariner's magnetic needle compass, the earlier military treatise of the Wujing Zongyao in 1044 had also described a thermoremanence compass.[77] This was a simple iron or steel needle that was heated, cooled, and placed in a bowl of water, producing the effect of weak magnetization, although its use was described only for navigation on land and not at sea.[77]

Literature

There were plenty of descriptions in Chinese literature of the time on the operations and aspects of seaports, maritime merchant shipping, overseas trade, and the sailing ships themselves. In 1117, the author Zhu Yu wrote not only of the magnetic compass for navigation, but also a hundred-foot line with a hook that was cast over the deck of the ship, used to collect mud samples at the bottom of the sea in order for the crew to determine their whereabouts by the smell and appearance of the mud.[78] In addition, Zhu Yu wrote of watertight bulkhead compartments in the hulls of ships to prevent sinking if damaged, the for-and-aft lug, taut mat sails, and the practice of beating-to-windward.[79] Confirming Zhu Yu's writing on Song dynasty ships with bulkhead hull compartments, in 1973 a 78-foot (24 m) long, 29-foot (8.8 m) wide Song trade ship from c. 1277 was dredged from the water near the southern coast of China that contained 12 bulkhead compartment rooms in its hull.[80] Maritime culture during the Song period was enhanced by these new technologies, along with the allowance of greater river and canal traffic. All around there was a bustling display of government run grain-tax transport ships, tribute vessels and barges, private shipping vessels, a multitude of busy fishers in small fishing boats, along with the rich enjoying the comforts of their luxurious private yachts.[81]

Besides Zhu Yu there were other prominent Chinese authors of maritime interests as well. In 1178, the Guangzhou customs officer Zhou Qufei, who wrote in Lingwai Daida about the Arab slave trade of Africans as far as Madagascar,[82] stated this about Chinese seagoing ships, their sizes, durability at sea, and the lives of those on board:

The ships which sail the southern sea and south of it are like houses. When their sails are spread they are like great clouds in the sky. Their

fermented on board. There is no account of dead or living, no going back to the mainland when once the people have set forth upon the caerulean sea. At daybreak, when the gong sounds aboard the ship, the animals can drink their fill, and crew and passengers alike forget all dangers. To those on board everything is hidden and lost in space, mountains, landmarks, and the countries of foreigners. The shipmaster may say 'To make such and such a country, with a favourable wind, in so many days, we should sight such and such a mountain, (then) the ship must steer in such and such a direction'. But suddenly the wind may fall, and may not be strong enough to allow of the sighting of the mountain on the given day; in such a case, bearings may have to be changed. And the ship (on the other hand) may be carried far beyond (the landmark) and may lose its bearings. A gale may spring up, the ship may be blown hither and thither, it may meet with shoals or be driven upon hidden rocks, then it may be broken to the very roofs (of its deckhouses). A great ship with heavy cargo has nothing to fear from the high seas, but rather in shallow water it will come to grief.[83]

The later Muslim

The sails of these vessels are made of strips of

Ibn Battuta then went on describing the means of their construction, and accurate depictions of separate bulkhead compartments in the hulls of the ships:

This is the manner in which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised, and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built, the lower deck is fitted in, and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished. The pieces of wood, and those parts of the hull, near the water(-line) serve for the crew to wash and to accomplish their natural necessities. On the sides of these pieces of wood also the oars are found; they are as big as masts, and are worked by 10 or 15 men (each), who row standing up.[84]

Although Ibn Battuta had mentioned the size of the sailing crew, he described the sizes of the vessels further, as well as the lavish merchant cabins on board:

The vessels have four decks, upon which there are cabins and saloons for merchants. Several of these 'mysria' contain cupboards and other conveniences; they have doors which can be locked, and keys for their occupiers. (The merchants) take with them their wives and concubines. It often happens that a man can be in his cabin without others on board realizing it, and they do not see him until the vessel has arrived in some port. The sailors also have their children in such cabins; and (in some parts of the ship) they sew garden herbs, vegetables, and ginger in wooden tubs. The Commander of such a vessel is a great

Ethiops (i.e. black slaves, yet in China these men-at-arms would have most likely been Malays) march before him bearing javelins and swords, with drums beating and trumpets blowing. When he arrives at the guesthouse where he is to stay, they set up their lances on each side of the gate, and mount guard throughout his visit.[85]

Paddle-wheel ships

During the Song dynasty there was also great amount of attention given to the building of efficient automotive vessels known as paddle wheel craft. The latter had been known in China perhaps since the 5th century,[86] and certainly by the Tang dynasty in 784 with the successful paddle wheel warship design of Li Gao.[86] In 1134, the Deputy Transport Commissioner of Zhejiang, Wu Ge, had paddle wheel warships constructed with a total of nine wheels and others with thirteen wheels.[87] However, there were paddle wheel ships in the Song that were so large that 12 wheels were featured on each side of the vessel.[88] In 1135 the famous general Yue Fei (1103–1142) ambushed a force of rebels under Yang Yao, entangling their paddle wheel craft by filling a lake with floating weeds and rotting logs, thus allowing them to board their ships and gain a strategic victory.[87] In 1161, gunpowder bombs and paddle wheel crafts were used effectively by the Song Chinese at the Battle of Tangdao and the Battle of Caishi along the Yangtze River against the Jurchen Jin dynasty during the Jin–Song Wars. The Jurchen invasion, led by Wanyan Liang (the Prince of Hailing), failed to conquer the Southern Song.[87]

In 1183, the

Metallurgy

The art of

The per capita

Due to the enormous amount of production, the economic historian Robert Hartwell noted that Chinese iron and coal production in the following 12th century was equal to if not greater than England's iron and coal production in the early phase of the

Wind power

The effect of wind power was appreciated in China long before the introduction of the

The

In the collection of the private works of the 'Placid Retired Scholar' (Zhan Ran Ju Shi), there are ten poems on Hechong Fu. One of these describes the scenery of that place […] and says that 'the stored wheat is milled by the rushing wind and the rice is pounded fresh by hanging pestles. The westerners (i.e. Turks) there use windmills (feng mo) just as the people of the south (i.e. the Southern Song) use watermills (shui mo). And when they pound they have the pesltes hanging vertically'.[113]

Here Sheng Ruozi quotes a written selection about windmills from the 'Placid Retired Scholar', who is actually

After the windmill, wind power applications in other devices and even vehicles were found in China. There was the 'sailing carriage' that appeared by at least the Ming dynasty in the 16th century (although it could have been known beforehand). European travelers to China in the late 16th century were surprised to find large single-wheel passenger and cargo wheelbarrows not only pulled by mule or horse, but also mounted with ship-like masts and sails to help push them along by the wind.[117]

Archaeology

During the early half of the

Geology and climatology

Shen Kuo also made hypotheses in regards to geology and climatology in his Dream Pool Essays of 1088. Shen believed that land was reshaped over time due to perpetual erosion, uplift, and deposition of silt, and cited his observance of horizontal strata of fossils embedded in a cliffside in the Taihang Mountains as evidence that the area was once the location of an ancient seashore that had shifted hundreds of miles east over an enormous span of time.[121][122][123] Shen also wrote that since petrified bamboos were found underground in a dry northern climate zone where they had never been known to grow, climates naturally shifted geographically over time.[123][124]

Forensics

Early concepts in

See also

- History of science and technology in China

- List of Chinese discoveries

- List of Chinese inventions

- List of inventions and discoveries of Neolithic China

- Science and technology of the Han dynasty

References

Citations

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 466.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 165 & 455.

- ^ a b Sivin, III, 22.

- ^ Sivin, III, 23.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, 618.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, 415–416.

- ^ Sivin, III, 16.

- ^ Sivin, III, 19.

- ^ a b Sivin, III, 18–19.

- ^ Unschuld, 60.

- ^ Wu, 5.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 446.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 569.

- ^ Wright, 213.

- ^ Sivin, III, 31–32.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 445.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 448.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 111.

- ^ a b c Ebrey, 162.

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 148.

- ^ Sivin, III, 17.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 98.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 283.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 284.

- ^ a b Sivin, III, 31.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 292.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 549.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-21484-2.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, Plate CCLXIX, Fig. 683.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 551.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 552.

- ^ Needham Volume 4, Part 2, 554.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 107.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 108.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 107-108.

- ^ Bowman, 105.

- ^ Ebrey, 238.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 217.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 1.

- ^ Ebrey, 156.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 122.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 48.

- ISBN 978-0-87220-915-2.

First known illustration of a fire lance and a grenade

- ISBN 978-962-209-188-7. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 77.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 80.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 81.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 82.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 81–83

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 89.

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 138.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 224–225.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 220–221.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 221.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 263–364.

- ^ Needham, Volume V, Part 7, 222.

- JSTOR 3105275.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 293.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 264.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 22.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 192.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 199.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 477.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 154.

- ^ Partington, 240.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 344–350.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 350.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 351.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 351–352.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 352.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 230–231.

- ^ Needham Volume 4, Part 3, 230.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 660, 200 feet.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 660.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 100.

- ^ a b Sivin, III, 21.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 279.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 463.

- ^ Ebrey, 159.

- ^ a b China. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. From Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved on 2007-06-28

- ^ Levathes, 37.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 464.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 469

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 470.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 31.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 421.

- ^ Morton, 104.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 422.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 423.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 563 g

- ^ Gernet, 69.

- ^ Morton, 287.

- ^ Hartwell, 53–54.

- ^ a b c Ebrey et al., 158.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wagner, 175.

- ^ Wagner, 177.

- ^ a b Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 144.

- ^ Embree, 339.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 390–392.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 393.

- ^ Embree, 712.

- ^ Wagner, 178–179.

- ^ Ebrey, 30.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 370.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 33.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 233.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 151.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 118.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, Plate CLVI.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 556.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 557.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 560.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 561.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 558.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 555.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 274–276.

- ^ ISBN 0-87023-495-1, 1986), p. 227.

- ISBN 0-521-66991-X), p. 148.

- ^ a b Rudolph, R.C. "Preliminary Notes on Sung Archaeology", The Journal of Asian Studies (Volume 22, Number 2, 1963): 169–177.

- ^ Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth (Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986) pp. 603–604, 618.

- ^ Nathan Sivin, Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. (Brookfield, Vermont: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing, 1995), Chapter III, p. 23.

- ^ ISBN 9971-69-259-7) p. 15.

- ^ Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth (Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986) p. 618.

- ^ McKnight, 155–157.

- ^ Gernet, 170.

- ^ Gernet, 170–171.

- ^ Haskell (2006), 432.

Sources

- Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X(paperback).

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1997). Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. Armonk: ME Sharpe, Inc.

- Gernet, Jacques (1982). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hartwell, Robert (1966). Markets, Technology and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry. Journal of Economic History 26.

- Haskell, Neal H. (2006). "The Science of Forensic Entomology," in Forensic Science and Law: Investigative Applications in Criminal, Civil, and Family Justice, 431–440. Edited by Cyril H. Wecht and John T. Rago. Boca Raton: CRC Press, an imprint of Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 0-8493-1970-6.

- Levathes (1994). When China Ruled the Seas. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-70158-4.

- McKnight, Brian E. (1992). Law and Order in Sung China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Morton, Scott and Charlton Lewis (2005). China: Its History and Culture: Fourth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3; Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology, the Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Partington, James Riddick (1960). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

- Unschuld, Paul U. (2003). Nature, Knowledge, Imagery in an Ancient Chinese Medical Text. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wagner, Donald B. "The Administration of the Iron Industry in Eleventh-Century China", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (Volume 44 2001): 175-197.

- Wright, David Curtis (2001) The History of China. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Wu, Jing-nuan (2005). An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica. New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

- Gunpowder and 'fire-weapons'

- Chinese Fire Arrows

- The History of Early Fireworks and Fire Arrows

- Gunpowder and Firearms in China

- Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity

- Other