Amphipolis

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Greek. (June 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Ἀμφίπολις Αμφίπολη | |

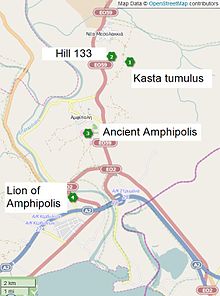

Amphipolis sites | |

| Location | Macedonia, Greece |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°49′6″N 23°50′24″E / 40.81833°N 23.84000°E |

| Type | Settlement |

Amphipolis (

Amphipolis was originally a

Excavations in and around the city have revealed important buildings, ancient walls and tombs. The finds are displayed at the

It was located within the region of Edonis.

History

Origins

Throughout the 5th century BC,

The new settlement took the name of Amphipolis (literally, "around the city"), a name which is the subject of much debate about its

Amphipolis quickly became the main power base of the Athenians in Thrace and, consequently, a target of choice for their Spartan adversaries. In 424 BC during the Peloponnesian War the Spartan general Brasidas captured Amphipolis.

Two years later in 422 BC, a new Athenian force under the general Cleon failed once more during the Battle of Amphipolis at which both Kleon and Brasidas lost their lives. Brasidas survived long enough to hear of the defeat of the Athenians and was buried at Amphipolis with impressive pomp. From then on he was regarded as the founder of the city[10][11] and honoured with yearly games and sacrifices.

The Athenian population remained very much in the minority in the city and hence Amphipolis remained an independent city and an ally of the Athenians, rather than a colony or member of the Athens-led Delian League. It entered a new phase of prosperity as a cosmopolitan centre.

Macedonian rule

The city itself kept its independence until the reign of king Philip II (r. 359 – 336 BC) despite several Athenian attacks, notably because of the government of Callistratus of Aphidnae. In 357 BC, Philip succeeded where the Athenians had failed and conquered the city, thereby removing the obstacle which Amphipolis presented to Macedonian control over Thrace. According to the historian Theopompus, this conquest came to be the object of a secret accord between Athens and Philip II, who would return the city in exchange for the fortified town of Pydna, but the Macedonian king betrayed the accord, refusing to cede Amphipolis and laying siege to Pydna as well.[12]

The city was not immediately incorporated into the Macedonian kingdom, and for some time preserved its institutions and a certain degree of autonomy. The border of Macedonia was not moved further east; however, Philip sent a number of Macedonian governors to Amphipolis, and in many respects the city was effectively "Macedonianized". Nomenclature, the calendar and the currency (the gold stater, created by Philip to capitalise on the gold reserves of the Pangaion hills, replaced the Amphipolitan drachma) were all replaced by Macedonian equivalents. In the reign of Alexander the Great, Amphipolis was an important naval base, and the birthplace of three of the most famous Macedonian admirals: Nearchus, Androsthenes[13] and Laomedon, whose burial place is most likely marked by the famous lion of Amphipolis.

The importance of the city in this period is shown by Alexander the Great's decision that it was one of the six cities at which large luxurious temples costing 1,500 talents were built. Alexander prepared for campaigns here against Thrace in 335 BC and his army and fleet assembled near the port before the invasion of Asia. The port was also used as naval base during his campaigns in Asia. After Alexander's death, his wife Roxana and their young son Alexander IV were exiled by Cassander and later murdered here.[14]

Throughout Macedonian sovereignty Amphipolis was a strong fortress of great strategic and economic importance, as shown by inscriptions. Amphipolis became one of the main stops on the Macedonian royal road (as testified by a border stone found between Philippi and Amphipolis giving the distance to the latter), and later on the Via Egnatia, the principal Roman road which crossed the southern Balkans. Apart from the ramparts of the lower town, the gymnasium and a set of well-preserved frescoes from a wealthy villa are the only artifacts from this period that remain visible. Though little is known of the layout of the town, modern knowledge of its institutions is in considerably better shape thanks to a rich epigraphic documentation, including a military ordinance of Philip V and an ephebarchic law from the gymnasium.[15]

Conquest by the Romans

After the final victory of

In the 1st c. BC the city was badly damaged in the

Revival in Late Antiquity

During the period of

Nevertheless, the number, size and quality of the churches constructed between the 5th and 6th centuries are impressive. Four

Final decline of the city

The Slavic invasions of the late 6th century gradually encroached on the back-country Amphipolitan lifestyle and led to the decline of the town, during which period its inhabitants retreated to the area around the acropolis. The ramparts were maintained to a certain extent, thanks to materials plundered from the monuments of the lower city, and the large unused cisterns of the upper city were occupied by small houses and the workshops of artisans. Around the middle of the 7th century, a further reduction of the inhabited area of the city was followed by an increase in the fortification of the town, with the construction of a new rampart with pentagonal towers cutting through the middle of the remaining monuments. The acropolis, the Roman baths, and especially the episcopal basilica were crossed by this wall.

The city was probably abandoned in the eighth century, as the last bishop was attested at the

Archaeology

The site was discovered and described by many travellers and archaeologists during the 19th century, including E. Cousinéry (1831) (engraver),

Parts of the lion monument and tombs were discovered during World War I by Bulgarian and British troops whilst digging trenches in the area. In 1934, M. Feyel, of the

The silver ossuary containing the cremated remains of Brasidas[19] and a gold crown (see image) was found in a tomb in pride of place under the Agora.

The Tomb of Amphipolis

In 2012[20] Greek archaeologists unearthed a large tomb within the Kasta Hill, the biggest burial mound in Greece, northeast of Amphipolis. The large size and quality of the tumulus indicates the prominence of the burials made there, and its dating and the connections of the city with Alexander the Great suggest important occupants. The perimeter wall of the tumulus is 497 m (544 yd) long, and is made of limestone covered with marble.

The tomb comprises three chambers separated by walls. There are two

Fragments of bones from 5 individuals were found in the cist tomb, the most complete of which is a 60+ year old woman in the deepest layer.[21] Dr. Katerina Peristeri, the archaeologist heading the excavation of the tomb, dates the tomb to the late 4th century BC, the period after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC). One theory is that the tomb was built for the mother of Alexander the Great, Olympias.[22]

Restoration of the tomb is due for completion in 2023[23] in the course of which building materials of the grave site which were later used by the Romans elsewhere will be rebuilt in their original location.

The city walls

The original 7.5 km long walls are generally visible, particularly the northern section which is preserved to a height of 7.5m. 5 preserved gates can be seen and notably the gate in front of the wooden bridge.

In early Christian times another, inner, wall was built around the acropolis.

The ancient wooden bridge of Amphipolis

The ancient bridge that crossed the river Strymon was mentioned by Thucydides,

It was discovered in 1977 and is a unique find for Greek antiquity.[25] The hundreds of wooden piles have been carbon-dated and show the vast life of the bridge with some piles dating from 760 BC, and others used till about 1800 AD.

The Gymnasium

This was a major public building for the military and gymnastic training of youth as well as for their artistic and intellectual education. It was built in the 4th c. BC and includes a

During the Macedonian era it became a major institution.

The stone

After it was destroyed in the 1st c. BC in the Thracian rebellion against Roman rule, it was rebuilt in Augustus's time in the 1st c. AD along with the rest of the city.

Amphipolitans

- Demetrius of Amphipolis, student of Plato

- Zoilus (400–320 BC), grammarian, cynic philosopher

- Pamphilus (painter), head of Sicyonian school and teacher of Apelles

- Aetion, sculptor

- Philippus of Amphipolis, historian

- Nearchus, admiral

- Erigyius, general

- Damasias of Amphipolis 320 BC StadionOlympics

- Hermagoras of Amphipolis (c. 225 BC), stoic philosopher, follower of Persaeus

- Apollodorus of Amphipolis, appointed joint military governor of Babylon and the other satrapies as far as Cilicia by Alexander the Great[26]

- Xena – In the television series Xena Warrior Princess, Amphipolis is the main character's home village.

See also

References

- ^ "Amfípolis: Greece, name, administrative division, geographic coordinates and map". Geographical Names. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ISBN 960-214-126-3

- ^ a b Badian, Ernst. "Rhoxane ii Alexander's Wife". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Thirlwall, Connop (1840). A History of Greece. Longmans. pp. 318–319.

- ^ Herodotus VII.107

- ^ Thucydides IV.102

- ^ Thucydides I, 100, 3

- ^ Lazaridis D. La cité grecque d’Amphipolis et son système de défense. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres. p 194–214.

- ^ Koukouli-Chrysanthaki Ch., "Excavating Classical Amphipoli", In (eds) Stamatopoulou M., and M., Yeroulanou <Excavating Classical Culture>, BAR International Series 1031, 2002:57–73

- ^ Agelarakis A., “Physical anthropological report on the cremated human remains of an individual retrieved from the Amphipolis agora”, In “Excavating Classical Amphipolis” by Koukouli-Chrysantkai Ch., <Excavating Classical Culture> (eds.) Stamatopoulou M., and M., Yeroulanou, BAR International Series 1031, 2002: 72–73.

- ^ Theopompus, Philippica

- ^ "Androsthenes Thasos – Google Search".

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library of History Book XIX, 52

- ^ Ephebarchic Law of Amphipolis – English translation

- ^ Acts 17:1

- ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 831

- ^ Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique (in French)

- ^ A. Agelarakis, “Physical anthropological report on the cremated human remains of an individual retrieved from the Amphipolis agora” in “Excvating Classical Amphipolis” by Ch. Koukouli-Chrysantkai, <Excavating Classical Culture> (eds.) Stamatopoulou M., and M., Yeroulanou, BAR International Series 1031, 2002: 72–73

- ^ Andrew Marszal (7 September 2014). "Marble female figurines unearthed in vast Alexander the Great–era Greek tomb". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Greek tomb at Amphipolis is 'important discovery'". BBC News. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ The Identity of the Occupant of the Amphipolis Tomb Beneath the Kasta Mound, Andrew Chugg, 2021, Macedonian Studies Journal, Volume II, Issue 1, https://www.academia.edu/80446098/The_Identity_of_the_Occupant_of_the_Amphipolis_Tomb_Beneath_the_Kasta_Mound

- ^ Pilot visits to the Kastas Mound in 2022 https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2022/03/21/pilot-visits-to-the-kastas-mound-in-2022/

- ^ History of the Peloponnesian War 4.103.5

- ^ Y Maniatis, D Malamidou, H Koukouli-Chryssanthaki, Y Facorellis, RADIOCARBON DATING OF THE AMPHIPOLIS BRIDGE IN NORTHERN GREECE, MAINTAINED AND FUNCTIONED FOR 2500 YEARS, RADIOCARBON, Vol 52, Nr 1, 2010, p 41–63, 2010 University of Arizona

- ^ Diodorus Siculus Library of History Book XVII