Miletus

Μῑ́λητος Milet | |

Aegean Region | |

| Coordinates | 37°31′49″N 27°16′42″E / 37.53028°N 27.27833°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 90 ha (220 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Minoans (later Mycenaeans) and then Ionians (the later on a former Anatolian site)[1][2][3] |

| Site notes | |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Miletus Archaeological Site |

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

Miletus

Evidence of the first settlement at the site has been made inaccessible by the rise of sea level and deposition of sediments from the Maeander. The first available evidence is of the

The 13th century BC saw the arrival of

The

History

Neolithic

The earliest available archaeological evidence indicates that the islands on which Miletus was originally placed were inhabited by a

Middle Bronze Age

The prehistoric archaeology of the Early and Middle Bronze Age portrays a city heavily influenced by society and events elsewhere in the Aegean, rather than inland.

Minoan period

The earliest Minoan settlement of Miletus dates to 2000 BC.[9] Beginning at about 1900 BC artifacts of the Minoan civilization acquired by trade arrived at the site.[8] For some centuries the location received a strong impulse from that civilization, an archaeological fact that tends to support but not necessarily confirm the founding legend—that is, a population influx from Crete. According to Strabo:[10]

Ephorus says: Miletus was first founded and fortified above the sea by Cretans, where the Miletus of olden times is now situated, being settled by Sarpedon, who brought colonists from the Cretan Miletus and named the city after that Miletus, the place formerly being in possession of the Leleges.

According to Pausanias, however, Miletus was a friend of Sarpedon from Crete, after whom the city was named.[11] Miletus had a son named Kelados, and the heroon of Kelados has been found at Panormos, a port of Miletus near Didyma.[12]

The legends recounted as history by the ancient historians and geographers are perhaps the strongest; the late mythographers have nothing historically significant to relate.[13]

Late Bronze Age

Recorded history at Miletus begins with the records of the

, in the Late Bronze Age.Mycenaean period

Miletus was a

Miletus is then mentioned in the "

The Milawata letter mentions a joint expedition by the Hittite king and a

In the last stage of LHIIIB, the citadel of Bronze Age Pylos counted among its female slaves a mi-ra-ti-ja, Mycenaean Greek for "women from Miletus", written in Linear B syllabic script.[18]

Fall of Miletus

During the collapse of Bronze Age civilization, Miletus was burnt again, presumably by the Sea Peoples.

Dark Age

Mythographers told that Neleus, a son of

Archaic period

The city of Miletus became one of the twelve

Miletus was one of the cities involved in the Lelantine War of the 8th century BC.

Ties with Megara

Miletus is known to have early ties with Megara in Greece. According to some scholars, these two cities had built up a "colonisation alliance". In the 7th/6th century BC they acted in accordance with each other.[20]

Both cities acted under the leadership and sanction of an Apollo oracle. Megara cooperated with that of Delphi. Miletus had her own oracle of Apollo Didymeus Milesios in Didyma. Also, there are many parallels in the political organisation of both cities.[20]

According to

In the late 7th century BC, the tyrant

.Miletus was an important center of philosophy and science, producing such men as

By the 6th century BC, Miletus had earned a maritime empire with many colonies, mainly scattered around the

First Achaemenid period

When Cyrus of Persia defeated Croesus of Lydia in the middle of the 6th century BC, Miletus fell under Persian rule. In 499 BC, Miletus's tyrant Aristagoras became the leader of the Ionian Revolt against the Persians, who, under Darius the Great, quashed this rebellion in the Battle of Lade in 494 BC and punished Miletus by selling all of the women and children into slavery, killing the men, and expelling all of the young men as eunuchs, thereby assuring that no Miletus citizen would ever be born again. A year afterward, Phrynicus produced the tragedy The Capture of Miletus in Athens. The Athenians fined him for reminding them of their loss.[26]

Classical Greek period

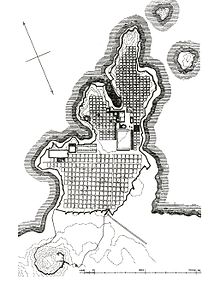

In 479 BC, the Greeks decisively defeated the Persians on the Greek mainland at the Battle of Plataea, and Miletus was freed from Persian rule. With many sanctuaries of Miletus having been destroyed by Persians. the restoration of them, however, was prohibited by the "Oath of the Ionians", which aims to retain the ruins as memorials. This oath was only partially practiced by Milesians, with some sanctuaries restored back to their Archaic appearances.[27] The city's gridlike layout was also constructed across all the area within the city wall, designed by Hippodamus of Miletus. It later became famous and labeled as the "Hippodamian plan", serving as the basic layout for the new foundations of Hellenistic and Roman cities.[24]

Second Achaemenid period

In 387 BC, the Peace of Antalcidas gave the Persian Achaemenid Empire under king Artaxerxes II control of the Greek city-states of Ionia, including Miletus.

In 358 BC, Artaxerxes II died and was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes III, who, in 355 BC, forced Athens to conclude a peace, which required its forces to leave Asia Minor (Anatolia) and acknowledge the independence of its rebellious allies.[citation needed]

Macedonian period

In 334 BC, the Siege of Miletus by the forces of Alexander the Great of Macedonia conquered the city. The conquest of most of the rest of Asia Minor soon followed. In this period, the city reached its greatest extent, occupying within its walls an area of approximately 90 hectares (220 acres).[28]

When Alexander died in 323 BC, Miletus came under the control of Ptolemy, governor of Caria, and his satrap of Lydia, Asander, who had become autonomous.[29] In 312 BC, Macedonian general Antigonus I Monophthalmus sent Docimus and Medeius to free the city and grant autonomy, restoring the democratic patrimonial regime. In 301 BC, after Antigonus I was killed in the Battle of Ipsus by the coalition of Lysimachus, Cassander, and Seleucus I Nicator, founder of the Seleucid Empire, Miletus maintained good relations with all the successors after Seleucus I Nicator made substantial donations to the sanctuary of Didyma and returned the statue of Apollo that had been stolen by the Persians in 494 BC.

In 295 BC, Antigonus I's son

Seleucid period

Around 287/286 BC Demetrius Poliorcetes returned, but failed to maintain his possessions and was imprisoned in Syria. Nicocles of Sidon, the commander of Demetrius' fleet surrendered the city. Lysimachus dominated until 281 BC, when he was defeated by the Seleucids at the Battle of Corupedium. In 280/279 BC the Milesians adopted a new chronological system based on the Seleucids.

Egyptian period

In 279 BC, the city was taken from Seleucid king

Roman period

After an alliance with Rome, in 133 BC the city became part of the province of Asia.

Miletus benefited from Roman rule and most of the present monuments date to this period.

The

In 262 new city walls were built.

However the harbour was silting up and the economy was in decline. In 538 emperor

Byzantine period

During the

Turkish rule

In the 15th century, the

The Ilyas Bey Complex from 1403 with its mosque is a Europa Nostra awarded cultural heritage site in Miletus.

Archaeological excavations

The first excavations in Miletus were conducted by the French archaeologist Olivier Rayet in 1873, followed by the German archaeologists Julius Hülsen and Theodor Wiegand[34][35][36] between 1899 and 1931. Excavations, however, were interrupted several times by wars and various other events. Carl Weickart excavated for a short season in 1938 and again between 1955 and 1957.[37][38][39] He was followed by Gerhard Kleiner and then by Wolfgang Muller-Wiener. Today, excavations are organized by the

.One remarkable artifact recovered from the city during the first excavations of the 19th century, the Market Gate of Miletus, was transported piece by piece to Germany and reassembled. It is currently exhibited at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. The main collection of artifacts resides in the Miletus Museum in Didim, Aydın, serving since 1973.

Archaeologists discovered a cave under the city's theatre and believe that it is a "sacred" cave which belonged to the cult of

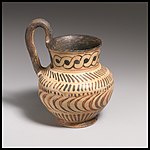

Examples of the Milesian Vase

- Artifacts

-

The name Fikellura derives from a site on the island of Rhodes to which this fabric has been attributed. It is now established that the center of production was Miletus.

-

Milesian Vase

-

Milesian Vase

-

Milesian Vase

-

Milesian Vase

Geography

The ruins appear on satellite maps at 37°31.8'N 27°16.7'E, about 3 km north of Balat and 3 km east of Batıköy in Aydın Province, Turkey.

In antiquity the city possessed a harbor at the southern entry of a large bay, on which two more of the traditional twelve Ionian cities stood: Priene and Myus. The harbor of Miletus was additionally protected by the nearby small island of Lade. Over the centuries the gulf silted up with alluvium carried by the Meander River. Priene and Myus had lost their harbors by the Roman era, and Miletus itself became an inland town in the early Christian era; all three were abandoned to ruin as their economies were strangled by the lack of access to the sea. There is a Great Harbor Monument where, according to the New Testament account, the apostle Paul stopped on his way back to Jerusalem by boat. He met the Ephesian Elders and then headed out to the beach to bid them farewell, recorded in the book of Acts 20:17-38.

Geology

During the Pleistocene epoch the Miletus region was submerged in the Aegean Sea. It subsequently emerged slowly, the sea reaching a low level of about 130 meters (430 ft) below present level at about 18,000 BP. The site of Miletus was part of the mainland.

A gradual rise brought a level of about 1.75 meters (5 ft 9 in) below present at about 5500 BP, creating several

Gallery

-

Sculpture from Baths of Faustina

-

Faustina Baths in Miletus

-

The Sacred Way from Miletus with the remains of the stoa

-

The Ionic Stoa on the Sacred Way

-

Remains of the stoa connecting the main Bath of Faustina to the Palaestra

-

Illustration of Miletus

-

Right entrance of the ancient Greek theatre

-

Ancient Greek theatre

Colonies

Miletus became known for the great number of colonies it founded. It was considered the greatest Greek metropolis and founded more colonies than any other Greek city.[43] Pliny the Elder (Natural History, 5.112) says that Miletus founded over 90 colonies. Among them are:[44]

- Abydos

- Amisos

- Apollonia Pontica

- Borysthenites (Berezan)

- Cardia

- Cius

- Colonae

- Cotyora

- Cyzicus

- Dioscurias

- Hermonassa

- Histria

- Kepoi

- Kerasous

- Lampsacus

- Leros

- Limnae

- Miletopolis

- Myrmekion(?)

- Nymphaion

- Odessos

- Olbia

- Paesus

- Panticapaeum

- Parium

- Patraeus

- Phanagoria

- Phasis

- Pityus

- Priapus

- Proconnesus

- Prusias (?)

- Sinope

- Scepsis

- Tanais

- Theodosia

- Tieion

- Tomis

- Tyras

- Tyritake

- Trapezunt

Notable people

- Arctinus of Miletus (775 BC – 741 BC), epic poet

- Thales (c. 624 BC – c. 546 BC), Pre-Socraticphilosopher

- Anaximander (c. 610 BC – c. 546 BC), Pre-Socratic philosopher and geographer

- Cadmus (fl. c. 550 BC), writer

- Anaximenes (c. 585 BC – c. 525 BC), Pre-Socratic philosopher

- Aristagoras (fl. 6th-5th century BC), Tyrant of Miletus

- Phocylides (born c. 560 BC), Greek gnomic poet

- Hecataeus (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), Greek historian

- Histiaeus (died 493 BC), ruler of Miletus

- Leucippus (fl. first half of 5th century BC), philosopher and originator of Atomism (his association with Miletus is traditional, but disputed)

- Hippodamus (c. 498 – 408 BC), urban planner

- Aspasia (c. 470 – 400 BC) courtesan, and mistress of Pericles, was born in Miletus

- Aristides(fl. 2nd century BC), writer

- Monime (died 72/71 BC), a Greek noblewoman and one of the wives of Mithridates VI Eupator

- Alexander Polyhistor (fl. 1st century AD), Greek scholar, born in Miletus before being taken as a slave to Rome

- Aeschines of Miletus (fl. 1st century AD), a distinguished orator in the Asiatic style

- Isidore (fl. 6th century AD), Greek architect

- Hesychius (fl. 6th century AD), Greek chronicler and biographer

- Timagenes or Timogenes, historian and rhetor[45]

- Philiscus of Miletus, rhetor. Teacher of Neanthes of Cyzicus[46]

- Hellanicus, historian[47]

- Dionysicles (Ancient Greek: Διονυσικλῆς) of Miletus, sculptor. One of his famous works was a statue, at Leonidaion, of Democrates of Tenedos who was an ancient Olympic winner at wrestling [48]

- Baccheius or Bacchius of Miletus (Βακχεῖος), a writer. He wrote a work on agriculture.[49]

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

Notes

- Latin: Mīlētus: Milet

- Turkish

References and sources

- References

- ISBN 978-90-04-25341-4.

- ISBN 978-0-203-99393-4.

The political history of Miletos/Millawanda, as it can be reconstructed from limited sources, shows that despite having a material culture dominated by Aegean influences it was more often associated with Anatolian powers such as Arzawa and the Hittites than it was with the presumed Aegean power of Ahhijawa

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

They had certainly been familiar with the territory earlier, in the Late Bronze Age, by way of commercial and political interests, and perhaps even trading posts, but now they came to stay. In the case of such settlements as Miletus and Ephesus, as implied, the Greeks chose the sites of former Anatolian cities of prominence.

- ^ Luc-Normand Tellier, Urban World History: An Economic and Geographical Perspective, p. 79: “The neighboring Greek city of Miletus, located on the Meander river was another terminal of the same route; it exerted certain hegemony over the Black sea trade and created about fifty commercial entrepôts in the Aegean sea and Black sea region...”

- ISBN 978-81-269-0775-5.

- ^ A Short History of Greek Philosophy By John Marshall page 11 “For several centuries prior to the great Persian invasion of Greece, perhaps the very greatest and wealthiest city of the Greek world was Miletus”

- ^ Ancient Greek civilization By David Sansone page 79 “In the seventh and sixth centuries BC the city of Miletus was among the most prosperous and powerful of Greek poleis.”

- ^ a b Crouch (2004) page 183.

- ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

- ^ Book 14 Section 1.6.

- ^ "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 7, chapter 2, section 5". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-36245-009-9, retrieved 8 March 2025

- is "starry".

- ^ Hajnal, Ivo. "Graeco-Anatolian Contacts in the Mycenaean Period". University of Innsbruck. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ Christopher Mee, Anatolia and the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age, p. 142

- ^ Mee, Anatolia and the Aegean, p. 139

- ^ https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/Iliad2.php#BkII811, Iliad, book II

- ^ Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages

- ^ "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 7, chapter 2, section 6". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ a b Alexander Herda (2015), Megara and Miletos: Colonising with Apollo. A Structural Comparison of Religious and Political Institutions in Two Archaic Greek Polis States; see Abstract at Alexander Herda research

- ^ Paus. i. 39. § 5, i. 40. § 6

- ^ Miletos, the ornament of Ionia: history of the city to 400 B.C.E by Vanessa B. Gorman (University of Michigan Press) 2001 – pg 123

- ISBN 0814765521.

- ^ a b Weber, B (2007). "Der Stadtplan von Milet". In Cobet, J; von Graeve, V; Niemeier, W.D.; Zimmermann, A (eds.). Frühes Ionien. Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Mainz am Rhein. pp. 327–362.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 978-0-203-99393-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-953566-8, retrieved 4 May 2022

- ISBN 978-2-503-58631-1, retrieved 8 March 2025

- ISBN 9780415200752.

- ^ 'The Life of Alexander the Great' by John Williams, Henry Ketcham, p. 89

- ^ Foundation of the Hellenic World. "Hellenistic Period". www.fhw.gr.[unreliable source?]

- ISBN 978-0-7546-5902-0

- ISBN 978-3-11-022704-8

- ^ "Miletus (Site)". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ISBN 1-141-62992-5

- ^ Theodor Wiegand and Julius Hülsen [Das Nymphaeum von Milet, Museen zu Berlin 1919] and Kurt Krausem, Die Milesische Landschaft, Milet II, vol. 2, Schoetz, 1929

- ^ Theodor Wiegand et al., Der Latmos, Milet III, vol. 1, G. Reimer, 1913

- ^ Carl Weickert, Grabungen in Milet 1938, Bericht über den VI internationalen Kongress für Archäologie, pp. 325-332, 1940

- ^ Carl Weickert, Die Ausgrabung beim Athena-Tempel in Milet 1955, Istanbuler Mitteilungen, Deutsche Archaeologische Institut, vol. 7, pp.102-132, 1957

- ^ Carl Weickert, Neue Ausgrabungen in Milet, Neue deutsche Ausgrabungen im Mittelmeergebiet und im Vorderen Orient, pp. 181-96, 1959

- ^ 'Sacred Cave' in ancient Miletos awaits visitors

- ^ The Ancient City of Miletos’s “Sacred Cave” Opened to Visitors

- ^ Crouch (2004) page 180.

- ^ Colony and Mother City in Ancient Greece By A. J. Graham page 98 “Judged by the number of its colonies Miletus was the most prolific of the Greek mother cities. For though some of the more extravagance claims made in antiquity have not been substantiated by modern investigations, her colonies were by far more numerous than those of any other Greek cities.”

- ISBN 978-90-04-12204-8.

- ^ Suda, tau, 590

- ^ Suda, nu, 114

- ^ Suda, epsilon, 738

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.17.1

- ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Baccheius

- Sources

- Crouch, Dora P. (2004). Geology and Settlement: Greco-Roman Patterns. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195083248.

Further reading

- Greaves, Alan M. (2002). Miletos: A History. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415238465.

- Gorman, Vanessa B. (2001). Miletos, the Ornament of Ionia: A History of the City to 400 B.C.E. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan University Press. ISBN 9780472111992.

External links

- Official website

- Ausgrabungen in Milet official site of the excavations in Miletus by Ruhr-Universität Bochum (in German)

- Ancient Coins of Miletus

- Livius picture archive: Miletus

- Some 250 pictures of site and museum

- Greek Inscriptions of Miletus in English translation

- The Theatre at Miletus, The Ancient Theatre Archive, Theatre specifications and virtual reality tour of theatre

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Details about most of the monuments

- Walking the sacred pagan path from Ancient Miletus to Didim