Ephesus

Ἔφεσος (Éphesos) Efes | |

The Library of Celsus in Ephesus | |

| Location | Selçuk, İzmir Province, Turkey, West Asia |

|---|---|

| Region | Ionia |

| Coordinates | 37°56′28″N 27°20′31″E / 37.94111°N 27.34194°E |

| Type | Ancient Greek settlement |

| Part of | West Asia |

| Area | Wall circuit: 415 ha (1,030 acres) Occupied: 224 ha (550 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Attic and Ionian Greeks |

| Founded | 10th century BC |

| Abandoned | 15th century |

| Periods | Greek Dark Ages to Late Middle Ages |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1863–1869, 1895 |

| Archaeologists | John Turtle Wood, Otto Benndorf |

| Website | www |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 1018 |

| Inscription | 2015 (39th Session) |

| Area | 662.62 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,246.3 ha |

Ephesus (/ˈɛfɪsəs/;[1][2] Greek: Ἔφεσος, translit. Éphesos; Turkish: Efes; may ultimately derive from Hittite: 𒀀𒉺𒊭, romanized: Apaša) was a city in Ancient Greece[3][4] on the coast of Ionia, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital,[5][6] by Attic and Ionian Greeks. During the Classical Greek era, it was one of twelve cities that were members of the Ionian League. The city came under the control of the Roman Republic in 129 BC.

The city was famous in its day for the nearby Temple of Artemis (completed around 550 BC), which has been designated one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.[7] Its many monumental buildings included the Library of Celsus and a theatre capable of holding 24,000 spectators.[8]

Ephesus was a recipient city of one of the

Today, the

History

Neolithic age

Humans had begun inhabiting the area surrounding Ephesus by the

Bronze Age

Excavations in recent years have unearthed settlements from the early Bronze Age at Ayasuluk Hill. According to Hittite sources, the capital of the kingdom of Arzawa (another independent state in Western and Southern Anatolia/Asia Minor[13]) was Apasa (or Abasa), and some scholars suggest that this is the same place the Greeks later called Ephesus.[5][14][15][16] In 1954, a burial ground from the Mycenaean era (1500–1400 BC), which contained ceramic pots, was discovered close to the ruins of the basilica of St. John.[17] This was the period of the Mycenaean expansion, a process that continued into the 13th century BC. The names Apasa and Ephesus appear to be cognate,[18] and recently found inscriptions seem to pinpoint the places in the Hittite record.[19][20]

Period of Greek migrations

Ephesus was founded as an Attic-Ionian colony in the 10th century BC on a hill (now known as the Ayasuluk Hill), three kilometers (1.9 miles) from the centre of ancient Ephesus (as attested by excavations at the

The Greek goddess

Ancient sources seem to indicate that an older name of the place was Alope (

Archaic period

About 650 BC, Ephesus was attacked by the

About 560 BC, Ephesus was conquered by the

Later in the same century, the Lydians under Croesus invaded Persia. The Ionians refused a peace offer from

Ephesus has intrigued archaeologists because for the Archaic Period there is no definite location for the settlement. There are numerous sites to suggest the movement of a settlement between the Bronze Age and the Roman period, but the silting up of the natural harbours as well as the movement of the Kayster River meant that the location never remained the same.

Classical period

Ephesus continued to prosper, but when taxes were raised under

During the Peloponnesian War, Ephesus was first allied to Athens[27] but in a later phase, called the Decelean War, or the Ionian War, sided with Sparta, which also had received the support of the Persians. As a result, rule over the cities of Ionia was ceded again to Persia.

These wars did not greatly affect daily life in Ephesus. The Ephesians were surprisingly modern in their social relations:[28] they allowed strangers to integrate and education was valued. In later times, Pliny the Elder mentioned having seen at Ephesus a representation of the goddess Diana by Timarete, the daughter of a painter.[29]

In 356 BC the temple of Artemis was burnt down, according to legend, by a lunatic called Herostratus. The inhabitants of Ephesus at once set about restoring the temple and even planned a larger and grander one than the original.

Hellenistic period

When

As the river

Ephesus revolted after the treacherous death of Agathocles, giving the Hellenistic king of Syria and Mesopotamia Seleucus I Nicator an opportunity for removing and killing Lysimachus, his last rival, at the Battle of Corupedium in 281 BC. After the death of Lysimachus the town again was named Ephesus.

Thus Ephesus became part of the

The Seleucid king

Classical Roman period (129 BC–395 AD)

Ephesus, as part of the kingdom of Pergamon, became a subject of the Roman Republic in 129 BC after the revolt of Eumenes III was suppressed.

The city felt Roman influence at once; taxes rose considerably, and the treasures of the city were systematically plundered. Hence in 88 BC Ephesus welcomed

King Ptolemy XII Auletes of Egypt retired to Ephesus in 57 BC, passing his time in the sanctuary of the temple of Artemis when the Roman Senate failed to restore him to his throne.[36]

Mark Antony was welcomed by Ephesus for periods when he was proconsul[37] and in 33 BC with Cleopatra when he gathered his fleet of 800 ships before the battle of Actium with Octavius.[38]

When

The city and temple were destroyed by the Goths in 263 AD. This marked the decline of the city's splendour. However emperor Constantine the Great rebuilt much of the city and erected new public baths.

The Roman population

Until recently, the population of Ephesus in Roman times was estimated to number up to 225,000 people by Broughton.[40][41] More recent scholarship regards these estimates as unrealistic. Such a large estimate would require population densities seen in only a few ancient cities, or extensive settlement outside the city walls. This would have been impossible at Ephesus because of the mountain ranges, coastline and quarries which surrounded the city.[42]

The wall of Lysimachus has been estimated to enclose an area of 415 hectares (1,030 acres). Not all of this area was inhabited due to public buildings and spaces in the city center and the steep slope of the Bülbül Dağı mountain, which was enclosed by the wall. Ludwig Burchner estimated this area with the walls at 1000 acres. Jerome Murphy-O'Connor uses an estimate of 345 hectares for the inhabited land or 835 acres (Murphey cites Ludwig Burchner). He cites Josiah Russell using 832 acres and Old Jerusalem in 1918 as the yardstick estimated the population at 51,068 at 148.5 persons per hectare. Using 510 persons per hectare, he arrives at a population between 138,000 and 172,500 .[43] J.W. Hanson estimated the inhabited space to be smaller, at 224 hectares (550 acres). He argues that population densities of 150~250 people per hectare are more realistic, which gives a range of 33,600–56,000 inhabitants. Even with these much lower population estimates, Ephesus was one of the largest cities of Roman Asia Minor, ranking it as the largest city after Sardis and Alexandria Troas.[44] Hanson and Ortman (2017)[45] estimate an inhabited area to be 263 hectares and their demographic model yields an estimate of 71,587 inhabitants, with a population density of 276 inhabitants per hectare. By contrast, Rome within the walls encompassed 1,500 hectares and as over 400 built-up hectares were left outside the Aurelian Wall, whose construction was begun in 274 AD and finished in 279 AD, the total inhabited area plus public spaces inside the walls consisted of ca. 1,900 hectares. Imperial Rome had a population estimated to be between 750,000 and one million (Hanson and Ortman's (2017)[45] model yields an estimate of 923,406 inhabitants), which imply in a population density of 395 to 526 inhabitants per hectare, including public spaces.

Byzantine Roman period (395–1308)

Ephesus remained the most important city of the Byzantine Empire in Asia after Constantinople in the 5th and 6th centuries.[46] Emperor Flavius Arcadius raised the level of the street between the theatre and the harbour. The basilica of St. John was built during the reign of emperor Justinian I in the 6th century.

Excavations in 2022 indicate that large parts of the city were destroyed in 614/615 by a military conflict, most likely during the Sasanian War, which initiated a drastic decline in the city's population and standard of living.[47]

The importance of the city as a commercial centre further declined as the harbour, today 5 kilometres inland, was slowly silted up by the river (today, Küçük Menderes) despite repeated dredging during the city's history.[48] The loss of its harbour caused Ephesus to lose its access to the Aegean Sea, which was important for trade. People started leaving the lowland of the city for the surrounding hills. The ruins of the temples were used as building blocks for new homes. Marble sculptures were ground to powder to make lime for plaster.

Sackings by the

When the

Pre-Ottoman period (1304–1390)

The town surrendered, on 24 October 1304, to Sasa Bey, a Turkish warlord of the

Shortly afterwards, Ephesus was ceded to the

The town knew again a short period of prosperity during the 14th century under these new

Ottoman period

Ephesians were incorporated as vassals into the

Ephesus was completely abandoned by the 15th century. Nearby Ayasuluğ (Ayasoluk being a corrupted form of the original Greek name[52]) was turkified to Selçuk in 1914.

Ephesus and Christianity

Ephesus was an important centre for

Roman Asia was associated with

According to

In the early 2nd century, the church at Ephesus was still important enough to be addressed by a letter written by Bishop Ignatius of Antioch to the Ephesians which begins with "Ignatius, who is also called Theophorus, to the Church which is at Ephesus, in Asia, deservedly most happy, being blessed in the greatness and fullness of God the Father, and predestinated before the beginning of time, that it should be always for an enduring and unchangeable glory" (Letter to the Ephesians). The church at Ephesus had given their support for Ignatius, who was taken to Rome for execution.

A legend, which was first mentioned by Epiphanius of Salamis in the 4th century, purported that Mary, the mother of Jesus, may have spent the last years of her life in Ephesus. The Ephesians derived the argument from John's presence in the city, and Jesus' instructions to John to take care of his mother, Mary, after his death. Epiphanius, however, was keen to point out that, while the Bible says John was leaving for Asia, it does not say specifically that Mary went with him. He later stated that she was buried in Jerusalem.[61] Since the 19th century, The House of the Virgin Mary, about 7 km (4 mi) from Selçuk, has been considered to have been the last home of Mary, mother of Jesus before her assumption into heaven in the Roman Catholic tradition, based on the visions of Augustinian sister the Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774–1824). It is a popular place of Catholic pilgrimage which has been visited by three recent popes.

The

Seven Sleepers

Ephesus is believed to be the city of the Seven Sleepers, who were persecuted by the Roman emperor Decius because of their Christianity, and they slept in a cave for three centuries, outlasting their persecution.

They are considered saints by Catholics and

Main sites

Ephesus is one of the largest Roman archaeological sites in the eastern Mediterranean. The visible ruins still give some idea of the city's original splendour, and the names associated with the ruins are evocative of its former life. The theatre dominates the view down Harbour Street, which leads to the silted-up harbour.

The Temple of Artemis, one of the

The Library of Celsus, the façade of which has been carefully reconstructed from original pieces, was originally built c. 125 in memory of

The interior of the library measured roughly 180 square metres (2,000 square feet) and may have contained as many as 12,000 scrolls.[70] By the year 400 C.E. the library was no longer in use after being damaged in 262 C.E. The facade was reconstructed during 1970 to 1978 using fragments found on site or copies of fragments that were previously removed to museums.[71]

At an estimated 25,000 seating capacity, the theatre is believed to be the largest in the ancient world.[8] This open-air theatre was used initially for drama, but during later Roman times gladiatorial combats were also held on its stage; the first archaeological evidence of a gladiator graveyard was found in May 2007.[72]

There were two agoras, one for commercial and one for state business.[73][74]

Ephesus also had several major

The city had one of the most advanced

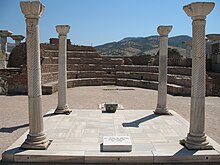

The Odeon was a small roofed theatre[77] constructed by Publius Vedius Antoninus and his wife around 150 AD. It was a small salon for plays and concerts, seating about 1,500 people. There were 22 stairs in the theatre. The upper part of the theatre was decorated with red granite pillars in the Corinthian style. The entrances were at both sides of the stage and reached by a few steps.[78]

The Temple of Hadrian dates from the 2nd century but underwent repairs in the 4th century and has been reerected from the surviving architectural fragments. The reliefs in the upper sections are casts, the originals now being exhibited in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum. A number of figures are depicted in the reliefs, including the emperor Theodosius I with his wife and eldest son.[79] The temple was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 20 million lira banknote of 2001–2005[80] and of the 20 new lira banknote of 2005–2009.[81]

The Temple of the Sebastoi (sometimes called the Temple of Domitian), dedicated to the Flavian dynasty, was one of the largest temples in the city. It was erected on a pseudodipteral plan with 8 × 13 columns. The temple and its statue are some of the few remains connected with Domitian.[79]

The Tomb/Fountain of Pollio was erected in 97 AD in honour of C. Sextilius Pollio, who constructed the Marnas aqueduct, by Offilius Proculus. It has a concave façade.[78][79]

A part of the site, Basilica of St. John, was built in the 6th century, under emperor Justinian I, over the supposed site of the apostle's tomb. It is now surrounded by Selçuk.

Archaeology

The history of archaeological research in Ephesus stretches back to 1863, when British architect John Turtle Wood, sponsored by the British Museum, began to search for the Artemision. In 1869 he discovered the pavement of the temple, but since further expected discoveries were not made the excavations stopped in 1874. In 1895 German archaeologist Otto Benndorf, financed by a 10,000 guilder donation made by Austrian Karl Mautner Ritter von Markhof, resumed excavations. In 1898 Benndorf founded the Austrian Archaeological Institute, which plays a leading role in Ephesus today.[82]

Finds from the site are exhibited notably in the Ephesos Museum in Vienna, the Ephesus Archaeological Museum in Selçuk and in the British Museum.

In October 2016, Turkey halted the works of the archeologists, which had been ongoing for more than 100 years, due to tensions between Austria and Turkey. In May 2018, Turkey allowed Austrian archeologists to resume their excavations.[83]

Notable people

- Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC), Presocratic philosopher [84]

- Hipponax (6th Century BC), poet

- Zeuxis (5th century BC), painter

- Parrhasius (5th century BC), painter

- Herostratus (d 356 BC), criminal

- Zenodotus (fl. 280 BC), grammarian and literary critic, first librarian of the Library of Alexandria

- Agasias (2nd century BC), Greek sculptor

- Menander (early 2nd century BC), historian

- Artemidorus Ephesius (c. 100 BC), geographer

- Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (c. 45 – before c. 120), founder of the Celsus library

- Publius Hordeonius Lollianus (1st century), sophist

- Rufus (1st century), physician

- Polycrates of Ephesus (130 – 196), bishop

- Soranus of Ephesus (1st–2nd century), physician

- Artemidorus (2nd century AD), diviner and author

- Xenophon (2nd–3rd century), novelist

- Maximus (4th century), Neoplatonic philosopher

- Sosipatra (4th century), Neoplatonic philosopher

- Manuel Philes (c. 1275 – 1345), Byzantine poet

See also

- Ancient settlements in Turkey

- Christianity in the 1st century

- Christianity in the 2nd century

- Christianity in the 3rd century

- Early centers of Christianity

- Early Christian art and architecture

- Early Christianity

- Nea Efesos

References

- ^ "Ephesus Definition & Meaning | Dictionary.com".

- ISBN 978-0-19-280710-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

Historical Overview A Greek city-state on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, at the mouth of Cayster River (Küçük Menderes), Ephesus ...

- ISBN 978-81-269-0775-5.

- ^ a b Hawkins, J. David (2009). "The Arzawa letters in recent perspective". British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (14): 73–83.

- ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

In the case of such settlements as Miletus and Ephesus, as implied, the Greeks chose the sites of former Anatolian cities of prominence

- ^ "accessed September 14, 2007". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-884964-02-2.

- ^ 2:1–7

- Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible, Palo Alto, Mayfield, 1985.

- ^ [VIII. Muze Kurtrma Kazilari Semineri ] Adil Evren – Cengiz Icten, pp 111–133 1997

- ^ [Arkeoloji ve Sanat Dergisi] – Çukuriçi Höyük sayi 92 ] Adil Evren 1998

- ISBN 975-17-2756-1.

- ]

- ISBN 978-90-5867-079-3.

- ^ J. David Hawkins (1998). ‘Tarkasnawa King of Mira: Tarkendemos, Boğazköy Sealings, and Karabel.’ Anatolian Studies 48:1–31.

- ^ Coskun Özgünel (1996). "Mykenische Keramik in Anatolien". Asia Minor Studien. 23.

- ^ Jaan Puhvel (1984). 'Hittite Etymological Dictionary Vol. 1(A)' Berlin, New York, Amsterdam: Mouton de Gruyter 1984–.

- ^ J.David Hawkins (2009). 'The Arzawa letters in recent perspective' British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 14 73–83.

- ^ Garstang, J. and O. R. Gurney (1959). 'The geography of the Hittite Empire' Occasional Publications of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara 5London.

- ^ Pausanias (1965). Description of Greece. New York: Loeb Classical Library. pp. 7.2.8–9.

- ^ "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology". Ancientlibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2009-06-21. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Johannes Toepffer: Alope 5.(in German) In: Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (RE). Vol. I,2, Stuttgart 1894, col. 1595 f.

- ISBN 0-19-283678-1.

- ISBN 978-1-55407-311-5.

- ^ Herodotus i. 141

- S2CID 162250367.

- JSTOR 43726616.

- ^ Pliny the Elder Naturalis historia xxxv.40.147.

- ^ Strabo (1923–1932). Geography (volume 1–7). Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. pp. 14.1.21.

- ^ Edwyn Robert Bevan, The House of Seleucus, Vol. 1 (E. Arnold, 1902), p. 119.

- ^ Wilhelm Pape, Wörterbuch der griechischen Eigennamen, Vol. 3 (Braunschweig, 1870), p. 145.

- ^ Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- ISBN 978-0-691-03169-9.

- Appian of Alexandria (c.95 AD-c.165 AD). "The Mithridatic wars". History of Rome. §§46–50. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-10-02.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - Dio Cassius. Historia Romana. 39.16.3.

- ^ Plutarch. Ant. 23'1-24'12.

- ^ Plutarch. Ant. 56.1–10.

- ^ Strabo. Geography. Vol. 1–7. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library / Harvard University Press. 14.1.24.

- ISBN 9780199602353.

- ISBN 9780199602353.

- ISBN 9780199602353.

- ISBN 978-0-8146-5259-6.

- ISBN 9780199602353.

- ^ S2CID 165770409.

- ISBN 978-0756545864.

- ^ "Ephesos: More than 1,400-year-old area of the city discovered under a burnt layer". Austrian Archaeological Institute. 2022-10-28. Archived from the original on 2022-10-28. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

- ^ Kjeilen, Tore (2007-02-20). "accessed September 24, 2007". Lexicorient.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Foss, Clive (1979) Ephesus after antiquity: a late antique, Byzantine, and Turkish city, Cambridge University Press, p. 121.

Gökovalı, Şadan; Altan Erguvan (1982) Ephesus, Ticaret Matbaacılık, p.7. - ^ Foss, Clive (1979). Ephesus After Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. 144.

- ^ Foss, Clive (1979). Ephesus After Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. viii.

- ^ "Bruce F.F., "St John at Ephesus", The John Rylands University Library, 60 (1978), p. 339" (PDF).

- ^ "Paul, St." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005

- ^ Acts 19:9

- ^ Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary on Acts 19 accessed 5 October 2015

- ^ Acts 19:1–7

- ^ Acts 19:23–41

- ^ Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "The Gospels" p. 266-268.

- ^ Eusebius (1965), "3.4", Historia Ecclesiastica [The History of the Church], Williamson, G.A. transl., Harmonsworth: Penguin, p. 109.

- ^ Vasiliki Limberis, 'The Council of Ephesos: The Demise of the See of Ephesos and the Rise of the Cult of the Theotokos' in Helmut Koester, Ephesos: Metropolis of Asia (2004), 327.

- ISBN 0-7546-0856-5.

- ^ The Revelation Explained: An Exposition, Text by Text, of the Apocalypse of St. John by F.G. Smith, 1918, public domain.

- ISBN 0-415-13591-5" "Apart from the public buildings for which such benefactors paid – the library at Ephesos, for example, recently reconstructed, built by Tiberius Iulius Aquila Polmaeanus in 110–20 in honour of his father Tiberius Iulius Celsus Polemaeanus, one of the earliest men of purely Greek origin to become a Roman consul

- ISBN 3-515-02393-3" "Ti. Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (PIR2 J 260) was a romanized Greek of Ephesus or Sardes who became the first eastern consul.

- OCLC 560733.

The Julio-Claudian emperors admitted relatively few Greeks to citizenship, but these showed satisfaction with their new position and privileges. Tiberius is known to have enfranchised only Tib. Julius Polemaeanus, ancestor of a prominent governor later in the century)

- ISBN 0-19-957780-3" "... and son of Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, proconsul of Asia, who founds the Celsian library from his own wealth ...

- ISBN 0-472-08420-8" "... statues (lost except for their bases) were probably of Celsus, consul in A.D. 92, and his son Aquila, consul in A.D. 110. A cuirass statue stood in the central niche of the upper storey. Its identification oscillates between Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, who is buried in a sarcophagus under the library, and Tiberius Julius Aquila Polemaeanus, who completed the building for his father

- ISBN 0-19-815231-0" "Sardis had already seen two Greek senators ... Ti. Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, cos. Suff. N 92 (Halfmann 1979: no 160), who endowed the remarkable Library of Celsus at Ephesus, and his son Ti. Julius Aquila Polemaeanus, cos. suff. in 110, who built most of it.

- ^ "Library of Celsus". World History Encyclopedia. 22 July 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Library of Celsus in Ephesus". Turkish Archeo News. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Kupper, Monika (2007-05-02). "Gladiators' graveyard discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Ephesus.us. "accessed September 21, 2007". Ephesus.us. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Ephesus.us. "State Agora, Ephesus Turkey". Ephesus.us. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Water Supply – ÖAI EN". www.oeai.at. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ "Ephesus Municipal Water System". homepage.univie.ac.at. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ "accessed September 24, 2007". Community.iexplore.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ ISBN 975-7559-48-2

- ^ ISBN 975-8212-11-7,

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group – Twenty Million Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 2008-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. Banknote Museum: 8. Emission Group – Twenty New Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 2009-02-24 at the Wayback Machine.

Announcement on the Withdrawal of E8 New Turkish Lira Banknotes from Circulation Archived April 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, 8 May 2007. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009. - ^ "Ephesos – An Ancient Metropolis: Exploration and History". Austrian Archaeological Institute. October 2008. Archived from the original on 2002-04-29. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ "Austrian minister thanks Turkey for resuming excavations in Ephesus". 4 May 2018.

- ^ theephesus.com. "accessed September 30, 2013". theephesus.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-17. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

Sources

- Foss, Clive. 1979. "Ephesus After Antiquity." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Athas, Daphne. 1991. Entering Ephesus. Sag Harbor, NY: Second Chance Press.

- Oster, Richard. 1987. A Bibliography of Ancient Ephesus. Philadelphia: American Theological Library Association.

- Scherrer, Peter, Fritz Krinzinger, and Selahattin Erdemgil. 2000. Ephesus: The New Guide. Rev. ed. 2000. Turkey: Ege Yayinlari (Zero Prod. Ltd.).

- Leloux, Kevin. 2018. "The Campaign Of Croesus Against Ephesus: Historical & Archaeological Considerations", in Polemos 21–2, p. 47–63.