Cattle egret

| Cattle egret | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding-plumaged adult in Wakodahatchee Wetlands. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Subfamily: | Ardeinae |

| Genus: | Bubulcus Bonaparte, 1855 |

| Species | |

|

) | |

| |

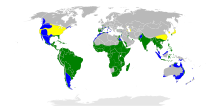

| Range of Bubulcus breeding non-breeding year-round

| |

The cattle egret (Bubulcus) is a

They are white birds adorned with buff

The adult cattle egret has few

Taxonomy

Before the description of the Bubulcus by

The eastern and western cattle egrets were split by McAllan and Bruce, Despite superficial similarities in appearance, the cattle egret is more closely related to the genus

An older English name for the cattle egret is buff-backed heron.[13]

Description

The cattle egret is a stocky heron with an 88–96 cm (34+1⁄2–38 in) wingspan; it is 46–56 cm (18–22 in) long and weighs 270–512 g (9+1⁄2–18 oz).[14] It has a relatively short, thick neck, a sturdy bill, and a hunched posture. The nonbreeding adult has mainly white plumage, a yellow bill, and greyish-yellow legs. During the breeding season, adults of the western cattle egret develop orange-buff plumes on the back, breast, and crown, and the bill, legs, and irises become bright red for a brief period prior to pairing.[15] The sexes are similar, but the male is marginally larger and has slightly longer breeding plumes than the female; juvenile birds lack coloured plumes and have a black bill.[14][16]

The eastern differs from the western in breeding plumage, when the buff colour on its head extends to the cheeks and throat, and the plumes are more golden in colour. This species' bill and tarsi are longer on average than in B. ibis.[17] B. i. seychellarum is smaller and shorter-winged than the other forms. It has white cheeks and throat, like B. ibis, but the nuptial plumes are golden, as with B. coromandus.[10] Individuals with abnormally grey, melanistic plumages have been recorded.[18][19]

The positioning of the egret's eyes allows for

Distribution and habitat

The western cattle egret has undergone one of the most rapid and wide-reaching natural expansions of any bird species.[23] It was originally native to parts of southern Spain and Portugal, tropical and subtropical Africa, and humid tropical and subtropical Asia. At the end of the 19th century, it began expanding its range into southern Africa, first breeding in the Cape Province in 1908.[24] Cattle egrets were first sighted in the Americas on the boundary of Guiana and Suriname in 1877, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean.[9][14] In the 1930s, the species is thought to have become established in that area.[25] It is now widely distributed across Brazil and was first discovered in the northern region of the country in 1964, feeding along with buffalos.[26]

The species first arrived in North America in 1941 (these early sightings were originally dismissed as escapees), bred in Florida in 1953, and spread rapidly, breeding for the first time in Canada in 1962.[24] It is now commonly seen as far west as California. It was first recorded breeding in Cuba in 1957, in Costa Rica in 1958, and in Mexico in 1963, although it was probably established before then.[25] In Europe, the species had historically declined in Spain and Portugal, but in the latter part of the 20th century, it expanded back through the Iberian Peninsula, and then began to colonise other parts of Europe, southern France in 1958, northern France in 1981, and Italy in 1985.[24] Breeding in the United Kingdom was recorded for the first time in 2008, only a year after an influx seen in the previous year.[27][28] In 2008, cattle egrets were also reported as having moved into Ireland for the first time.[29] This trend has continued and cattle egrets have become more numerous in southern Britain with influxes in some numbers during the nonbreeding seasons of 2007/08 and 2016/17. They bred in Britain again in 2017, following an influx in the previous winter, and may become established there.[30][31]

In Australia, the colonisation began in the 1940s, with the eastern cattle egret establishing itself in the north and east of the continent.[32] It began to regularly visit New Zealand in the 1960s. Since 1948, the cattle egret has been permanently resident in Israel. Prior to 1948, it was only a winter visitor.[33]

The massive and rapid expansion of the cattle egret's

In addition to the natural expansion of its range, cattle egrets have been

Although the cattle egret sometimes feeds in shallow water, unlike most herons, it is typically found in fields and dry grassy habitats, reflecting its greater dietary reliance on terrestrial insects rather than aquatic prey.[38]

Migration and movements

Some populations of cattle egrets are migratory, others are dispersive, and distinguishing between the two can be difficult.

Young birds are known to disperse up to 5,000 km (3,000 mi) from their breeding area. Flocks may fly vast distances and have been seen over seas and oceans including in the middle of the Atlantic.[42]

-

Cattle egret near Chandigarh.

Ecology and behavior

Voice

The cattle egret gives a quiet, throaty rick-rack call at the breeding colony, but is otherwise largely silent.[23]

Breeding

The cattle egret nests in colonies, which are often found around bodies of water.[23] The colonies are usually found in woodlands near lakes or rivers, in swamps, or on small inland or coastal islands, and are sometimes shared with other wetland birds, such as herons, egrets, ibises, and cormorants. The breeding season varies within South Asia.[8] Nesting in northern India begins with the onset of monsoons in May.[43] The breeding season in Australia is November to early January, with one brood laid per season.[44] The North American breeding season lasts from April to October.[23] In the Seychelles, the breeding season of B. i. seychellarum is April to October.[45]

The male displays in a tree in the colony, using a range of

The cattle egret engages in low levels of brood parasitism, and a few instances have been reported of cattle egret eggs being laid in the nests of snowy egrets and little blue herons, although these eggs seldom hatch.[23] Also, evidence of low levels of intraspecific brood parasitism has been found, with females laying eggs in the nests of other cattle egrets. As much as 30% extra-pair copulations has been noted.[49][50]

The dominant factor in nesting mortality is starvation. Sibling rivalry can be intense, and in South Africa, third and fourth chicks inevitably starve.[47] In the dryer habitats with fewer amphibians, the diet may lack sufficient vertebrate content and may cause bone abnormalities in growing chicks due to calcium deficiency.[51] In Barbados, nests were sometimes raided by vervet monkeys,[9] and a study in Florida reported the fish crow and black rat as other possible nest raiders. The same study attributed some nestling mortality to brown pelicans nesting in the vicinity, which accidentally, but frequently, dislodged nests or caused nestlings to fall.[52] In Australia, Torresian crows, wedge-tailed eagles, and white-bellied sea eagles take eggs or young, and tick infestation and viral infections may also be causes of mortality.[16]

-

Cattle egret egg

-

Adult feeding a nestling inApenheulzoo

-

Juvenile on Maui (note black bill)

Feeding

The cattle egret feeds on a wide range of prey, particularly

A cattle egret will weakly defend the area around a grazing animal against others of the same species, but if the area is swamped by egrets, it will give up and continue foraging elsewhere. Where numerous large animals are present, cattle egrets selectively forage around species that move at around 5–15 steps per minute, avoiding faster and slower moving herds; in Africa, cattle egrets selectively forage behind

The cattle egret sometimes shows versatility in its diet. On islands with

Threats

Pairs of crested caracaras have been observed chasing cattle egrets in flight, forcing them to the ground, and killing them.[64]

Status

The IUCN Red List treats them as a single species. They have a large range, with an estimated global extent of occurrence of 355,000,000 km2 (100,000,000 sq mi). Their global population is estimated to be 3.8–6.7 million individuals. For these reasons, the genus is evaluated as

Relationship with humans

As a conspicuous genus, the cattle egret has attracted many

The cattle egret is a popular bird with cattle

Not all interactions between humans and cattle egrets are beneficial. The cattle egret can be a safety hazard to aircraft due to its habit of feeding in large groups in the grassy verges of airports,

References

- ^ .

- ^ Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1855). "[untitled]". Annales des Sciences Naturelles comprenant la zoologie (in French). 4 (1): 141.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae [Stockholm]: Laurentii Salvii. p. 144.

A. capite laevi, corpore albo, rostro flavescente apice pedibusque nigris

- ^ Valpy, Francis Edward Jackson (1828). An Etymological Dictionary of the Latin Language. London; A. J. Valpy. p. 56.

- Webster's. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ISBN 0-9587516-0-9.

- ^ ISBN 84-87334-67-9.

- ^ JSTOR 1521386.

- ^ JSTOR 4081328.

- JSTOR 4087238.

- ISBN 0-19-518323-1.

- ^ "Western Cattle Egret". Avibase. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "Cattle Egret". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- S2CID 35761953.

- ^ ISBN 0-643-09133-5.

- ^ Biber, Jean-Pierre. "Bubulcus ibis (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). Appendix 3. CITES. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Willoughby, P. J. (2001). "Melanistic Cattle Egret". British Birds. 94: 390–391.

- ^ Herkenrath, Peter (2002). "Another melanistic cattle egret" (PDF). British Birds. 95: 531.

- PMID 7953610.

- S2CID 21430848.

- S2CID 11941872.

- ^ doi:10.2173/bna.113. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ ISBN 84-87334-09-1.

- ^ JSTOR 4511880.

- doi:10.3897/neobiota.21.4966 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "First cattle egrets breed in UK". BBC News. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ Nightingale, Barry; Dempsey, Eric (2008). "Recent reports" (PDF). British Birds. 101 (2): 108.

- ^ Barrett, Anne (15 January 2008). "Flying in ... to make new friends down on the farm". Irish Independent.

- ^ "Cattle Egrets breeding in Cheshire". Rare Bird Alert. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (29 June 2019). "Hello exotic egrets, farewell mountain butterflies as fauna revolution hits UK". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Maddock, M. (1990). "Cattle Egrets: South to Tasmania and New Zealand for the winter" (PDF). Notornis. 37 (1): 1–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Arnold, Paula (1962). Birds of Israel. Haifa, Israel: Shalit Publishers Ltd. p. 17.

- ^ Botkin, D.B. (2001). "The naturalness of biological invasions". Western North American Naturalist. 61 (3): 261–266.

- ^ Silva, M.P.; Coria, N.E.; Favero, M.; Casaux, R.J. (1995). "New Records of Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis, Blacknecked Swan Cygnus melancoryhyphus and White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis from the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 23: 65–66.

- ^ Dutson, G.; Watling, D. (2007). "Cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) and other vagrant birds in Fiji" (PDF). Notornis. 54 (4): 54–55.

- ^ ISBN 0-582-46055-7.

- ISBN 0-691-05054-6.

- ^ Seedikkoya, K.; Azeez, P.A.; Shukkur, E.A.A. (2005). "Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis habitat use and association with cattle" (PDF). Forktail. 21: 174–176.

- ISBN 0-12-430130-4.

- ^ Santharam, V. (1988). "Further notes on the local movements of the Pond Heron Ardeola grayii". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 28 (1–2): 8–9.

- JSTOR 1521007.

- ^ Hilaluddin; Kaul, Rahul; Hussain, Mohd Shah; Imam, Ekwal; Shah, Junid N.; Abbasi, Faiza; Shawland, Tahir A. (2005). "Status and distribution of breeding cattle egret and little egret in Amroha using density method" (PDF). Current Science. 88 (25): 1239–1243.

- ^ ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- ISBN 0-7136-3973-3.

- ISBN 0-19-553068-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-854981-4.

- PMID 4154173.

- JSTOR 4085616.

- JSTOR 4087617.

- PMID 16107676.

- JSTOR 4085265.

- .

- ^ Hosein, Melinda (2012). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago (PDF). pp. 1–4.

- JSTOR 2402882.

- JSTOR 4084294.

- ^ Chaturvedi, N. (1993). "Dietary of the cattle egret Bubulcus ibis coromandus (Boddaert)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 90 (1): 90.

- JSTOR 4160720.

- JSTOR 2424157.

- ^ Devasahayam, A. (2009). "Foraging behaviour of cattle egret in an unusual habitat". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 49 (5): 78.

- JSTOR 3676738.

- JSTOR 4083130.

- .

- ^ de Godoy, Fernando Igor; Macarrão, Arthur; Costa, Julio César (June 2020). "Hunting behaviour of Southern Caracara Caracara plancus on medium-sized birds". Cotinga. 42: 28–30.

- ^ "Bubulcus ibis (bird)". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- JSTOR 4075029.

- ^ Tidemann, Sonia; Gosler, Andrew, eds. (2010). Ethno-ornithology: Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Society. Routledge. p. 288.

- .

- ISBN 0-8248-0213-6.

- ^ Breese, P.L. (1959). "Information on Cattle Egret, a Bird New to Hawaii". Elepaio. 20. Hawaii Audubon Society: 33–34.

- ^ Paton, P.; Fellows, D.; Tomich, P. (1986). "Distribution of Cattle Egret Roosts in Hawaii With Notes on the Problems Egrets Pose to Airports". Elepaio. 46 (13): 143–147.

- ^ Fagbohun, O.A.; Owoade, A.A.; Oluwayelu, D.O.; Olayemi, F.O. (2000). "Serological survey of infectious bursal disease virus antibodies in cattle egrets, pigeons and Nigerian laughing doves". African Journal of Biomedical Research. 3 (3): 191–192.

- ^ "Heartwater" (PDF). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ Fagbohun, O.A.; Oluwayelu, D.O.; Owoade, A.A.; Olayemi, F.O. (2000). "Survey for antibodies to Newcastle Disease virus in cattle egrets, pigeons and Nigerian laughing doves" (PDF). African Journal of Biomedical Research. 3: 193–194.

External links

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Cattle Egret - The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Cattle egret photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)