Duchenne muscular dystrophy

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

braces , speech therapy, occupational therapy,

surgery, | |

| Medication | Corticosteroids |

| Prognosis | life expectancy: 28–30 years |

| Frequency | In males, 1 in 3,500-6,000[3] In females, 1 in 50,000,000[5] |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe type of

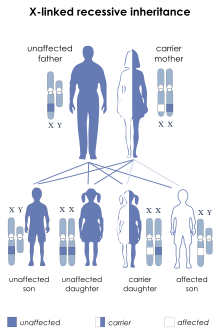

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is caused by mutations and/or deletions in any of the 79 exons encoding the large dystrophin protein, which is essential for maintaining the muscle fiber's cell membrane integrity.[3] The disorder follows an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern, with approximately two-thirds of cases inherited from the mother and one-third resulting from a new mutation.[3] Diagnosis can frequently be made at birth through genetic testing, and elevated creatine kinase levels in the blood are indicative of the condition.[3]

While there is no known cure, management strategies such as

Various figures of the occurrence of Duchenne muscular dystrophy are reported. One source reports that it affects about one in 3,500 to 6,000 males at birth.[3] Another source reports Duchenne muscular dystrophy being a rare disease and having an occurrence of 7.1 per 100,000 male births.[8] A number of sources referenced in this article indicate an occurrence of 6 per 100,000.[9]

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common type of muscular dystrophy,[3] with a median life expectancy of 28–30 years.[10][11] However, with comprehensive care, some individuals may live into their 30s or 40s.[3] Duchenne muscular dystrophy is considerably rarer in females, occurring in approximately one in 50,000,000 live female births.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Duchenne muscular dystrophy causes progressive

Signs usually appear before age five, and may even be observed from the moment a boy takes his first steps.

A classic sign of Duchenne muscular dystrophy is trouble getting up from lying or sitting position,

Non musculoskeletal manifestations of Duchenne muscular dystrophy occur. There is a higher risk of neurobehavioral disorders (e.g.,

Cause

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is caused by a mutation of the dystrophin gene, located on the short arm of the X chromosome (locus Xp21)[22] that codes for dystrophin protein. Mutations can either be inherited or occur spontaneously during germline transmission,[citation needed] causing a large reduction or absence of dystrophin, a protein that provides structural integrity in muscle cells.[23] Dystrophin is responsible for connecting the actin cytoskeleton of each muscle fiber to the underlying basal lamina (extracellular matrix), through a protein complex containing many subunits. The absence of dystrophin permits excess calcium to penetrate the sarcolemma (the cell membrane).[24]

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is extremely rare in females (about 1 in 50,000,000 female births).[5] It can occur in females with an affected father and a carrier mother, in those who are missing an X chromosome, or those who have an inactivated X chromosome (the most common of the rare reasons).[25] The daughter of a carrier mother and an affected father will be affected or a carrier with equal probability, as she will always inherit the affected X-chromosome from her father and has a 50% chance of also inheriting the affected X-chromosome from her mother.[26]

Disruption of the blood–brain barrier has been seen to be a noted feature in the development of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[27]

Diagnosis

Duchenne muscular dystrophy can be detected with about 95% accuracy by genetic studies performed during pregnancy.[18]

DNA test

The muscle-specific isoform of the dystrophin gene is composed of 79

Muscle biopsy

If DNA testing fails to find the mutation, a muscle biopsy test may be performed.

Prenatal tests

A prenatal test can be considered when the mother is a known or suspected carrier.[33]

Prior to invasive testing, determination of the fetal sex is important; while males are sometimes affected by this X-linked disease, female Duchenne muscular dystrophy is extremely rare. This can be achieved by ultrasound scan at 16 weeks or more recently by free fetal DNA (cffDNA) testing. Chorion villus sampling (CVS) can be done at 11–14 weeks, and has a 1% risk of miscarriage. Amniocentesis can be done after 15 weeks, and has a 0.5% risk of miscarriage.

Treatment

No cure for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is known.[35]

Treatment is generally aimed at controlling symptoms to maximize the quality of life which can be measured using specific questionnaires,[36] and include:

- Corticosteroids such as prednisolone, deflazacort and Vamorolone (Agamree) lead to short-term improvements in muscle strength and function up to 2 years.[37] Corticosteroids have also been reported to help prolong walking, though the evidence for this is not robust.[38]

- Disease-specific physical therapy is helpful to maintain muscle strength, flexibility, and function. It aims to:[39]

- Minimize the development of contractures and deformity by developing a programme of stretches and exercises where appropriate

- Anticipate and minimize other secondary complications of a physical nature by recommending bracing and durable medical equipment[40]

- Monitor respiratory function and advise on techniques to assist with breathing exercises and methods of clearing secretions[39]

- Orthopedic appliances (such as braces and wheelchairs) may improve mobility and the ability for self-care. Form-fitting removable leg braces that hold the ankle in place during sleep can defer the onset of contractures.

- Appropriate respiratory support as the disease progresses is important.

- Cardiac problems may require a pacemaker.[41]

The medication eteplirsen, a Morpholino antisense oligo, has been approved in the United States for the treatment of mutations amenable to dystrophin exon 51 skipping. The US approval has been controversial[42] as eteplirsen failed to establish a clinical benefit;[43] it has been refused approval by the European Medicines Agency.[44][45]

The medication ataluren (Translarna) is approved for use in the European Union.[46][47]

The

The Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide viltolarsen (Viltepso) was approved for medical use in the United States in August 2020, for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in people who have a confirmed mutation of the DMD gene that is amenable to exon 53 skipping.[50] It is the second approved targeted treatment for people with this type of mutation in the United States.[50] Approximately 8% of people with DMD have a mutation that is amenable to exon 53 skipping.[50]

Casimersen (Amondys 45) was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2021,[51] and it is the first FDA-approved targeted treatment for people who have a confirmed mutation of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene that is amenable to exon 45 skipping.[51]

Comprehensive multidisciplinary care guidelines for Duchenne muscular dystrophy have been developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and were published in 2010.[29] An update was published in 2018.[52][53]

In March 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for givinostat (Duvyzat), an oral medication, to be used in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in people aged six years and older. Givinostat is the first nonsteroidal drug to receive FDA approval for the treatment of all genetic variants of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Functioning as a histone deacetylase (Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, givinostat operates by targeting pathogenic processes within the body, ultimately leading to a reduction in inflammation and muscle loss associated with the disease.[56]

Prognosis

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a rare progressive disease which eventually affects all voluntary muscles and involves the heart and breathing muscles in later stages. Life expectancy is estimated to be around 25–26,[18][57] but this varies. People born with Duchenne muscular dystrophy after 1990 have a median life expectancy of approximately 28–30.[11][10] With excellent medical care, affected men often live into their 30s.[58] David Hatch of Paris, Maine, may have been the oldest person in the world with the disease; he lived to the age of 56.[59][60]

The most common direct cause of death in people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy is respiratory failure. Complications from treatment, such as mechanical ventilation and tracheotomy procedures, are also a concern. The next leading cause of death is cardiac-related conditions such as heart failure brought on by dilated cardiomyopathy. With respiratory assistance, the median survival age can reach up to 40. In rare cases, people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy have been seen to survive into their forties or early fifties, with proper positioning in wheelchairs and beds, and the use of ventilator support (via tracheostomy or mouthpiece), airway clearance, and heart medications.[61] Early planning of the required supports for later-life care has shown greater longevity for people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[62]

Curiously, in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the lack of dystrophin is associated with increased calcium levels and skeletal muscle myonecrosis. The intrinsic laryngeal muscles (ILMs) are protected and do not undergo myonecrosis.[63] ILMs have a calcium regulation system profile suggestive of a better ability to handle calcium changes in comparison to other muscles, and this may provide a mechanistic insight for their unique pathophysiological properties.[64] In addition, patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy also have elevated plasma lipoprotein levels, implying a primary state of dyslipidemia in patients.[65]

Epidemiology

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common type of muscular dystrophy; it affects about one in 5,000 males at birth.[3] Duchenne muscular dystrophy has an incidence of one in 3,600 male infants.[18]

In the US, a 2010 study showed a higher amount of those with Duchenne muscular dystrophy age ranging from 5 to 54 who are Hispanic compared to non-Hispanic Whites, and non-Hispanic Blacks.[66][67]

History

The disease was first described by the Neapolitan physician Giovanni Semmola in 1834 and Gaetano Conte in 1836.

Society and culture

Notable cases

- Alfredo Ferrari was an Italian automotive engineer, the eldest son of automaker Enzo Ferrari, and the planned heir to his father's sports car company, Ferrari. Alfredo died of DMD on 30 June 1956 at the age of 24.[73][74]

- Rapper and disability rights advocate Darius Weems had the disease and used his notoriety to raise awareness and funds for treatment, as seen in the documentary Darius Goes West (2007).[75] He died at the age of 27 in 2016.[76]

- Jonathan Evison's novel, The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, published in 2012, depicted a young man affected by the disease. In 2016, Netflix released The Fundamentals of Caring, a film based on the novel.[77]

Research

This section needs to be updated. (August 2019) |

Efforts are ongoing to find medications that either return the ability to make dystrophin or utrophin.[78] Other efforts include trying to block the entry of calcium ions into muscle cells.[79]

Exon-skipping

Two kinds of antisense oligos, 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate oligos (like Drisapersen) and Morpholino oligos (like eteplirsen), have tentative evidence of benefit and are being studied.[83] Eteplirsen is targeted to skip exon 51.[83] "As an example, skipping exon 51 restores the reading frame of ~ 15% of all the boys with deletions. It has been suggested that by having 10 AONs to skip 10 different exons it would be possible to deal with more than 70% of all DMD boys with deletions."[80] This represents about 1.5% of cases.[80]

People with

Gene therapy

Researchers are working on a gene editing method to correct a mutation that leads to Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

Genome editing through the CRISPR/Cas9 system is not currently feasible in humans. However, it may be possible, through advancements in technology, to use this technique to develop therapies for DMD in the future.[93][94] In 2007, researchers did the world's first clinical (viral-mediated) gene therapy trial for Duchenne MD.[95]

Future developments

Several medications designed to address the root cause are under development, including

References

- ^ "Duchenne". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "NINDS Muscular Dystrophy Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Muscular Dystrophy". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). 30 October 2023. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ PMID 28123647.

- ^ "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ https://catalog.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/muscular-dystrophy-hope-through-research.pdf Archived 31 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- PMID 32503598.

- ^ "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)". Muscular Dystrophy Association. 17 November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ PMID 32107739.

- ^ PMID 34645707.

- ^ a b c d e "Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Genetic and Rare Diseases (GARD) Information Center. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- PMID 23182642.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4684-4907-5. Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ PMID 20301298.

- ISBN 978-0-19968148-8. Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Muscular dystrophy - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- S2CID 895379.

- PMID 24838810.

- PMID 28974727.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Muscular Dystrophy, Duchenne Type; DMD - 310200

- PMID 35360042.

- ^ "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Pathophysiological Implications of Mitochondrial Calcium Signaling and ROS Production". 2 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Wahl M (21 October 2016). "Quest - Article - But Girls Don't Get Duchenne, or Do They? - A Quest Article". Muscular Dystrophy Association. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "Understanding Genetics". 26 November 2021. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- PMID 22292807.

- ^ "University of Utah Muscular Dystrophy". Genome.utah.edu. 28 November 2009. Archived from the original on 14 September 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ S2CID 328499.

- PMID 8411068.

- S2CID 13474827.

- PMID 12632325.

- PMID 30151283.

- PMID 21828326.

- ^ "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Statement". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 31 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- S2CID 25834947.

- PMID 26457695.

- PMID 27149418.

- ^ a b "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy". Physiopedia. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- PMID 31606891.

- PMID 21245364.

- PMID 27824847.

- ^ "FDA grants accelerated approval to first drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "CHMP Advises Against Approval for Eteplirsen in DMD". Medscape. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Exondys". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Translarna EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Translarna - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "FDA grants accelerated approval to first targeted treatment for rare Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutation" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 12 December 2019. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Vyondys 53 (golodirsen)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "FDA Approves Targeted Treatment for Rare Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mutation" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 12 August 2020. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "FDA Approves Targeted Treatment for Rare Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mutation" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- PMID 29395989.

- PMID 29395990.

- ^ "FDA Approves First Gene Therapy for Treatment of Certain Patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 June 2023. Archived from the original on 29 November 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Sarepta Therapeutics Announces FDA Approval of Elevidys, the First Gene Therapy to Treat Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy" (Press release). Sarepta Therapeutics. 22 June 2023. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "FDA Approves Nonsteroidal Treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 21 March 2024. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-1701-5.

- ^ "Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Muscular Dystrophy Campaign". Muscular-dystrophy.org. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Carter N (14 January 2021). "Nursing home resident defies COVID, wants to eat out again". Sun Journal. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "Obituaries - Cliff Gray Cremations and Funeral Services". February 2022. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- PMID 23876223.

- PMID 3504593.

- S2CID 41968787.

- PMID 26109185.

- S2CID 219741257.

- ^ "Population-Based Prevalence of Duchenne and Becker Muscular Dystrophies in the United States". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 5 January 2018. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- PMID 25687144.

- Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli. Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ De Rosa G (October 2005). "Da Conte a Duchenne" [By Conte in Duchenne]. DM (in Italian). Unione Italiana Lotta alla Distrofia Muscolare. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- PMID 21574522.

- ^ "Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Medterms.com. 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Who Named It?

- ^ Susanna Kim (21 October 2015). "What You Didn't Know About the Ferrari Family". ABC News. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ The GearShifters Team (13 September 2022). "How Did Dino Ferrari Die?". GearShifters. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ McFadden C, Johnson E, Effron L (22 November 2012). "Darius Weems' Next Chapter: Rap Star With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Tries Clinical Trial". ABC News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Eric Johnson (10 October 2016). "Disability Rights Activist Darius Weems Loses Battle with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy". ABC News. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ Berkshire G (23 January 2016). "Sundance Film Review: 'The Fundamentals of Caring'". Variety. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- PMID 28486179.

- PMID 20237582.

- ^ from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- PMID 9618164.

- PMID 20519671.

- ^ a b "FDA grants accelerated approval to first drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ S2CID 4349360.

- PMID 8378346.

- PMID 10944225.

- PMID 12181431.

- S2CID 20678312.

- PMID 17285139.

- PMID 29404407.

- S2CID 92204241.

- S2CID 48357156.

- PMID 25123483.

- ^ Wade N (31 December 2015). "Gene Editing Offers Hope for Treating Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Studies Find". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- PMID 17846262.

- PMID 16391721.

- ^ "NINDS Muscular Dystrophy Information Page". NINDS. 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

External links

- Muscular Dystrophies at Curlie