Maritime Silk Road

The Maritime Silk Road or Maritime Silk Route

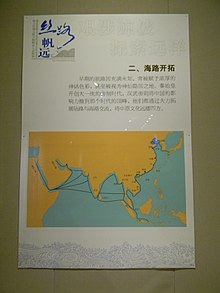

History

The Maritime Silk Road is a relatively new trading network compared to other historical networks of Asia. The

These networks of jade and spice would later help establish the Maritime Silk Road, which slowly began by 200 BCE, but only flourished later on, coinciding with existing and older trade networks.Austronesian

Prior to the 10th century, the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian traders, although

By the 10th to 13th centuries, the

After a brief cessation of Chinese trade in the 14th century due to internal famines and droughts in China, the

By the 16th century, the

The Qing dynasty initially continued the Ming philosophy of viewing trade as "tribute" to the court. However, increasing economic pressure finally forced the

Archaeology

The evidence of naval trade activities were shipwrecks recovered from the Java Sea — the Arabian dhow Belitung wreck dated to c. 826, the 10th century Intan wreck, and the Western-Austronesian vessel Cirebon wreck dated to the end of the 10th century.[4]: 12

Extent

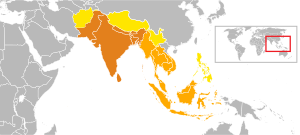

The trade route encompassed numbers of seas and ocean; including

World Heritage nomination

In May 2017, experts from various fields have held a meeting in London to discuss the proposal to nominate "Maritime Silk Route" as a new

See also

- Belitung shipwreck

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Cirebon shipwreck

- Foreign policy of China

- Indian Ocean trade

- List of ports and harbours of the Indian Ocean

- Maritime Silk Route Museum, Guangdong Province, China

- Ming treasure voyages led by Admiral Zheng He

- Project Mausam by India

- Tapayan

- String of Pearls (Indian Ocean)

- 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

References

- ISBN 978-1-4331-7040-9.

- ^ "Maritime Silk Road". SEAArch.

- ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Guan, Kwa Chong (2016). "The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea" (PDF). NSC Working Paper (23): 1–30.

- ^ ISSN 1835-1794.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link - ^ a b c Turton, M. (17 May 2021). "Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south". Taipei Times. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Everington, K. (6 September 2017). "Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar". Taiwan News. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-971-94292-0-3.

- ^ ISBN 9781588395245.

- ^ ISBN 978-0415100540.

- ISBN 9783319338224.

- ISBN 0-203-39126-8.

- S2CID 140665305.

- ISBN 9780812205022.

- ISBN 9780199271863.

- ^ "UNESCO Expert Meeting for the World Heritage Nomination Process of the Maritime Silk Routes". UNESCO.

- ^ a b Cultural Selection: The Early Maritime Silk Roads and the Emergence of Stone Ornament Workshops in Southeast Asian Port Settlements. UNESCO.

- ^ a b Everington, K. (7 December 2020). "Taiwanese banned from all UNESCO events". Taiwan News. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Taiwanese shut out of UNESCO events - Taipei Times". Taipei Times. 7 December 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2021.