Proboscidea

| Proboscidea | |

|---|---|

| |

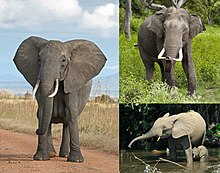

| Proboscidean diversity: Loxodonta cyclotis

| |

| |

| Skeleton of Moeritherium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Mirorder: | Tethytheria |

| Order: | Proboscidea Illiger, 1811 |

| Subclades | |

Proboscidea (

Extinct members of Proboscidea include the

Evolution

Over 180 extinct members of Proboscidea have been described.[3] The earliest proboscideans, Eritherium and Phosphatherium are known from the late Paleocene of Africa.[4] The Eocene included Numidotherium, Moeritherium and Barytherium from Africa. These animals were relatively small and some, like Moeritherium and Barytherium were probably amphibious.[5][6]

A major event in proboscidean evolution was the collision of Afro-Arabia with Eurasia, during the Early

Over the course of the

The following cladogram is based on endocasts[14]

| Proboscidea |

|

"plesielephantiforms" "mastodonts" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Morphology

Over the course of their evolution, proboscideans experienced a significant increase in body size. Some members of the families Deinotheriidae, Mammutidae, Stegodontidae and Elephantidae are thought to have exceeded modern elephants in size, with shoulder heights over 4 metres (13 ft) and masses over 10 tonnes (22,000 lb).[15] As with other megaherbivores, including the extinct sauropod dinosaurs, the large size of proboscideans likely developed to allow them to survive on vegetation with low nutritional value.[16] Their limbs grew longer and the feet shorter and broader.[17] The feet were originally plantigrade and developed into a digitigrade stance with cushion pads and the sesamoid bone providing support, with this change developing around the common ancestor of Deinotheriidae and Elephantiformes.[18] Members of Elephantiformes which have retracted nasal regions of the skull indicating the development of a trunk, as well as well-developed tusks on the upper and lower jaws.[19]

The skull grew larger, especially the cranium, while the neck shortened to provide better support for the skull. The increase in size led to the development and elongation of the mobile trunk to provide reach. The number of

The molar teeth changed from being replaced vertically as in other mammals to being replaced horizontally in the clade Elephantimorpha.[23] While early Elephantimorpha generally had lower jaws with an elongated mandibular symphysis at the front of the jaw with well developed lower tusks/incisors, from the Late Miocene onwards, many groups convergently developed brevirostrine (shortened) lower jaws with vestigial or no lower tusks.[24][25] Elephantids are distinguished from other proboscideans by a major shift in the molar morphology to parallel lophs rather than the cusps of earlier proboscideans, allowing them to become higher crowned (hypsodont) and more efficient in consuming grass.[26]

Dwarfism

Several species of proboscideans lived on islands and experienced

Ecology

It has been suggested that members of Elephantimorpha, including mammutids,[30] gomphotheres,[31] and stegodontids,[32] lived in herds like modern elephants. Analysis of remains of the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) suggest that like modern elephants, that herds consisted of females and juveniles and that adult males lived solitarily or in small groups, and that adult males periodically engaged in fights with other males during periods similar to musth found in living elephants. These traits are suggested to be inherited from the last common ancestor of elephantimorphs,[30] with musth-like behaviour also suggested to have occurred in gomphotheres.[33] All elephantimorphs are suggested to have been capable of communication via infrasound, as found in living elephants.[34]

Classification

Below is an unranked taxonomy of proboscidean genera as of 2019.[35][36][37][38]

- Order Proboscidea Illiger, 1811

- †Eritherium Gheerbrant, 2009

- †Moeritherium Andrews, 1901

- †Saloumia Tabuce et al., 2019

- †Family Numidotheriidae Shoshani & Tassy, 1992

- †Phosphatherium Gheerbrant et al., 1996

- †Arcanotherium Delmer, 2009

- †Daouitherium Gheerbrant & Sudre, 2002

- †Numidotherium Mahboubi et al., 1986

- †Family Barytheriidae Andrews, 1906

- †Omanitherium Seiffert et al., 2012

- †Barytherium Andrews, 1901

- †Family Deinotheriidae Bonaparte, 1845

- †Chilgatherium Sanders et al., 2004

- †Prodeinotherium Ehik, 1930

- †Deinotherium Kaup, 1829

- Suborder Elephantiformes Tassy, 1988

- †Eritreum Shoshani et al., 2006

- †Hemimastodon Pilgrim, 1912

- †Palaeomastodon Andrews, 1901

- †Phiomia Andrews & Beadnell, 1902

- Infraorder Elephantimorpha Tassy & Shoshani, 1997

- †Family Mammutidae Hay, 1922

- †Losodokodon Rasmussen & Gutierrez, 2009

- †Eozygodon Tassy & Pickford, 1983

- †Zygolophodon Vacek, 1877

- †Sinomammut Mothé et al., 2016

- †MammutBlumenbach, 1799

- Parvorder Elephantida Tassy & Shoshani, 1997

- †Family Choerolophodontidae Gaziry, 1976

- †Afrochoerodon Pickford, 2001

- †Choerolophodon Schlesinger, 1917

- †Family Amebelodontidae Barbour, 1927

- †Afromastodon Pickford, 2003

- †Progomphotherium Pickford, 2003

- †Eurybelodon Lambert, 2016

- †Serbelodon Frick, 1933

- †Archaeobelodon Tassy, 1984

- †Protanancus Arambourg, 1945

- †Amebelodon Barbour, 1927

- †Konobelodon Lambert, 1990

- †Torynobelodon Barbour, 1929

- †Aphanobelodon Wang et al., 2016

- †Platybelodon Borissiak, 1928

- †Family paraphyletic)

- "trilophodont gomphotheres"

- †Gomphotherium Burmeister, 1837

- †Blancotherium May, 2019

- †Gnathabelodon Barbour & Sternberg, 1935

- †Eubelodon Barbour, 1914

- †Stegomastodon Pohlig, 1912

- †Sinomastodon Tobien et al., 1986

- †Notiomastodon Cabrera, 1929

- †Rhynchotherium Falconer, 1868

- †Cuvieronius Osborn, 1923

- "tetralophodont gomphotheres"

- †Anancus Aymard, 1855

- †Paratetralophodon Tassy, 1983

- †Pediolophodon Lambert, 2007

- †Tetralophodon Falconer, 1857

- "trilophodont gomphotheres"

- Superfamily Elephantoidea Gray, 1821

- †Family Stegodontidae Osborn, 1918

- †Stegolophodon Schlesinger, 1917

- †Stegodon Falconer, 1857

- Family Elephantidae Gray, 1821

- †Subfamily StegotetrabelodontinaeAguirre, 1969

- †Stegodibelodon Coppens, 1972

- †Stegotetrabelodon Petrocchi, 1941

- †SelenotheriumMackaye, Brunet & Tassy, 2005

- Subfamily ElephantinaeGray, 1821

- †Primelephas Maglio, 1970

- LoxodontaAnonymous, 1827

- †Palaeoloxodon Matsumoto, 1924

- †MammuthusBrookes, 1828

- Elephas Linnaeus, 1758

- †Subfamily

- †Family Stegodontidae Osborn, 1918

- †Family Choerolophodontidae Gaziry, 1976

- †Family Mammutidae Hay, 1922

References

- ^ Illiger, Johann Karl Wilhelm (1811). Prodromus Systematis Mammalium et Avium: Additis Terminis Zoographicis Utriusque Classis, Eorumque Versione Germanica. Berolini: Sumptibus C. Salfeld. p. 62.

- ^ S2CID 2092950.

- ISBN 9781408189962. Archivedfrom the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- PMID 19549873.

- ^ Sukumar, pp. 13–16.

- PMID 18413605.

- ^ S2CID 235712060.

- ^ H. Saegusa, H. Nakaya, Y. Kunimatsu, M. Nakatsukasa, H. Tsujikawa, Y. Sawada, M. Saneyoshi, T. Sakai Earliest elephantid remains from the late Miocene locality, Nakali, Kenya Scientific Annals, School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece VIth International Conference on Mammoths and Their Relatives, vol. 102, Grevena -Siatista, special volume (2014), p. 175

- ISSN 2571-550X.

- .

- S2CID 206639522.

- ISBN 978-1-78570-965-4, retrieved 14 April 2020

- PMID 28253255.

- ISBN 978-3-031-13982-6, retrieved 22 May 2023

- .

- ^ Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus Cope, 1878". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. Vol. 36. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- ^ PMID 21238404.

- from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-315-11891-8.

- S2CID 21216371.

- S2CID 55095894.

- ISSN 0891-2963.

- S2CID 89904463.

- PMID 26756209.

- .

- S2CID 883007.

- ^ a b c Sukumar, pp. 31–33.

- S2CID 4249191.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISSN 0923-9308.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 35696566.

- PMID 21152772.

- S2CID 129206332.

- .

- ISBN 978-3-031-13982-6, retrieved 20 April 2024

- .

- S2CID 89063787.

- PMID 26756209.

- S2CID 213978026.

Bibliography

- Nowak, Ronald M. (1999), Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, LCCN 98023686

- Haynes, Gary (1993), Mammoths, Mastodonts, and Elephants: Biology, Behavior and the Fossil Record (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521456913

- Sukumar, R. (11 September 2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behaviour, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, USA. OCLC 935260783.