René Descartes: Difference between revisions

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers 235,825 edits No edit summary |

Rescuing 4 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) (Balon Greyjoy) |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

Descartes apparently started giving lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week, at 5 a.m, in her cold and draughty castle. Soon it became clear they did not like each other; she did not like his [[Mechanical philosophy#Descartes and the mechanical philosophy|mechanical philosophy]], nor did he appreciate her interest in [[Ancient Greek]]. <!--Mid January Christina left the city for three weeks.--> By 15 January 1650, Descartes had seen Christina only four or five times. On 1 February he contracted pneumonia and died on 11 February.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/41497065|title=Math and mathematicians: the history of math discoveries around the world|last=Bruno|first=Leonard C.|date=2003|origyear=1999|publisher=U X L|others=Baker, Lawrence W.|year=|isbn=0787638137|location=Detroit, Mich.|pages=104|oclc=41497065}}</ref> The cause of death was [[pneumonia]] according to Chanut, but [[pleurisy|peripneumonia]] according to the doctor Van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him.<ref>[http://rue89.nouvelobs.com/2010/02/12/il-y-a-des-preuves-que-rene-descartes-a-ete-assassine-138138 Rue89.nouvelobs.com]</ref> (The winter seems to have been mild,<ref>[http://www.int-res.com/articles/cr/17/c017p055.pdf Severity of winter seasons in the northern Baltic Sea between 1529 and 1990: reconstruction and analysis by S. Jevrejeva, p.6, Table 3]</ref> except for the second half of January which was harsh as described by Descartes himself; however, "this remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes' take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather."<ref name="Smith"/>) |

Descartes apparently started giving lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week, at 5 a.m, in her cold and draughty castle. Soon it became clear they did not like each other; she did not like his [[Mechanical philosophy#Descartes and the mechanical philosophy|mechanical philosophy]], nor did he appreciate her interest in [[Ancient Greek]]. <!--Mid January Christina left the city for three weeks.--> By 15 January 1650, Descartes had seen Christina only four or five times. On 1 February he contracted pneumonia and died on 11 February.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/41497065|title=Math and mathematicians: the history of math discoveries around the world|last=Bruno|first=Leonard C.|date=2003|origyear=1999|publisher=U X L|others=Baker, Lawrence W.|year=|isbn=0787638137|location=Detroit, Mich.|pages=104|oclc=41497065}}</ref> The cause of death was [[pneumonia]] according to Chanut, but [[pleurisy|peripneumonia]] according to the doctor Van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him.<ref>[http://rue89.nouvelobs.com/2010/02/12/il-y-a-des-preuves-que-rene-descartes-a-ete-assassine-138138 Rue89.nouvelobs.com]</ref> (The winter seems to have been mild,<ref>[http://www.int-res.com/articles/cr/17/c017p055.pdf Severity of winter seasons in the northern Baltic Sea between 1529 and 1990: reconstruction and analysis by S. Jevrejeva, p.6, Table 3]</ref> except for the second half of January which was harsh as described by Descartes himself; however, "this remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes' take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather."<ref name="Smith"/>) |

||

In 1996 E. Pies, a German scholar, published a book questioning this account, based on a letter by Johann van Wullen, who had been sent by Christina to treat him, something Descartes refused, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since.<ref>Pies Е., ''Der Mordfall Descartes'', Solingen, 1996, and Ebert Т., ''Der rätselhafte Tod des René Descartes'', Aschaffenburg, Alibri, 2009. French translation: ''L'Énigme de la mort de Descartes'', Paris, Hermann, 2011</ref> Descartes might have been assassinated<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/feb/14/rene-descartes-poisoned-catholic-priest|title=Descartes was "poisoned by Catholic priest" – ''The Guardian'', Feb 14 2010|work=The Guardian|accessdate=8 October 2014}}</ref><ref name="stockholmnews.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.stockholmnews.com/more.aspx?NID=4867 |title=Was Descartes murdered in Stockholm? |date=22 February 2010 |website=Stockholm News}}{{self-published source|date=August 2015}}</ref> as he asked for an [[emetic]]: wine mixed with tobacco.<ref>[http://philosophyonthemesa.com/tag/theodor-ebert/ Philosophyonthemesa.com]</ref> {{Dubious|date=October 2017}} |

In 1996 E. Pies, a German scholar, published a book questioning this account, based on a letter by Johann van Wullen, who had been sent by Christina to treat him, something Descartes refused, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since.<ref>Pies Е., ''Der Mordfall Descartes'', Solingen, 1996, and Ebert Т., ''Der rätselhafte Tod des René Descartes'', Aschaffenburg, Alibri, 2009. French translation: ''L'Énigme de la mort de Descartes'', Paris, Hermann, 2011</ref> Descartes might have been assassinated<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/feb/14/rene-descartes-poisoned-catholic-priest|title=Descartes was "poisoned by Catholic priest" – ''The Guardian'', Feb 14 2010|work=The Guardian|accessdate=8 October 2014}}</ref><ref name="stockholmnews.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.stockholmnews.com/more.aspx?NID=4867 |title=Was Descartes murdered in Stockholm? |date=22 February 2010 |website=Stockholm News |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20141215213819/http://www.stockholmnews.com/more.aspx?NID=4867 |archivedate=15 December 2014 |df=dmy-all }}{{self-published source|date=August 2015}}</ref> as he asked for an [[emetic]]: wine mixed with tobacco.<ref>[http://philosophyonthemesa.com/tag/theodor-ebert/ Philosophyonthemesa.com]</ref> {{Dubious|date=October 2017}} |

||

<!--In May 1654 Queen Christina abdicated her throne to convert to Catholicism half a year later in [[Antwerp]]. --> |

<!--In May 1654 Queen Christina abdicated her throne to convert to Catholicism half a year later in [[Antwerp]]. --> |

||

| Line 273: | Line 273: | ||

* {{cite book |last=Garber |first=Daniel |last2=Ayers |first2=Michael |authorlink2=Michael R. Ayers |year=1998 |title=The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy |location=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=0-521-53721-5}} |

* {{cite book |last=Garber |first=Daniel |last2=Ayers |first2=Michael |authorlink2=Michael R. Ayers |year=1998 |title=The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy |location=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=0-521-53721-5}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Gaukroger |first=Stephen |authorlink=Stephen Gaukroger |year=1995 |title=Descartes: An Intellectual Biography |location=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0-19-823994-7}} |

* {{cite book |last=Gaukroger |first=Stephen |authorlink=Stephen Gaukroger |year=1995 |title=Descartes: An Intellectual Biography |location=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0-19-823994-7}} |

||

* Gillespie, A. (2006). [http://stir.academia.edu/documents/0011/0112/Gillespie_Descartes_demon_a_dialogical_analysis_of_meditations_on_first_philosophy.pdf Descartes' demon: A dialogical analysis of 'Meditations on First Philosophy.'] Theory & Psychology, 16, 761–781. |

* Gillespie, A. (2006). [https://web.archive.org/web/20100618050955/http://stir.academia.edu/documents/0011/0112/Gillespie_Descartes_demon_a_dialogical_analysis_of_meditations_on_first_philosophy.pdf Descartes' demon: A dialogical analysis of 'Meditations on First Philosophy.'] Theory & Psychology, 16, 761–781. |

||

* {{cite book |last=Grayling |first=A.C. |authorlink=A. C. Grayling |year=2005 |title=Descartes: The Life and times of a Genius |location=New York |publisher=Walker Publishing Co., Inc. |isbn=0-8027-1501-X}} |

* {{cite book |last=Grayling |first=A.C. |authorlink=A. C. Grayling |year=2005 |title=Descartes: The Life and times of a Genius |location=New York |publisher=Walker Publishing Co., Inc. |isbn=0-8027-1501-X}} |

||

* [[Martin Heidegger|Heidegger, Martin]] [1938] (2002) ''The Age of the World Picture'' in [https://books.google.com/books?id=QImd2ARqQPMC&pg=PA66 ''Off the beaten track''] pp. 57–85 |

* [[Martin Heidegger|Heidegger, Martin]] [1938] (2002) ''The Age of the World Picture'' in [https://books.google.com/books?id=QImd2ARqQPMC&pg=PA66 ''Off the beaten track''] pp. 57–85 |

||

| Line 304: | Line 304: | ||

* [http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Mathematicians/Descartes.html Detailed biography of Descartes at MacTutor] |

* [http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Mathematicians/Descartes.html Detailed biography of Descartes at MacTutor] |

||

* {{Cite CE1913|wstitle=René Descartes}} |

* {{Cite CE1913|wstitle=René Descartes}} |

||

* [http://www.freewebs.com/dqsdnlj/d.html John Cottingham translation of ''Meditations'' and ''Objections and Replies''.] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20081220142538/http://www.freewebs.com/dqsdnlj/d.html John Cottingham translation of ''Meditations'' and ''Objections and Replies''.] |

||

* [http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/modlangfrench/20/ René Descartes (1596–1650)] Published in ''Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition'' (1996) |

* [http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/modlangfrench/20/ René Descartes (1596–1650)] Published in ''Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition'' (1996) |

||

* [http://www.earlymoderntexts.com A site containing Descartes's main works, including correspondence, slightly modified for easier reading] |

* [http://www.earlymoderntexts.com A site containing Descartes's main works, including correspondence, slightly modified for easier reading] |

||

| Line 317: | Line 317: | ||

'''Bibliographies''' |

'''Bibliographies''' |

||

* [http://www.cartesius.net/menu-demo/bibliografia-cartesiana ''Bibliografia cartesiana/Bibliographie cartésienne on-line (1997-2012)''] |

* [https://archive.is/20160110112345/http://www.cartesius.net/menu-demo/bibliografia-cartesiana ''Bibliografia cartesiana/Bibliographie cartésienne on-line (1997-2012)''] |

||

'''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''' |

'''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''' |

||

Revision as of 01:18, 2 December 2017

René Descartes | |

|---|---|

conservation of momentum (quantitas motus)[1] | |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| René Descartes |

|---|

|

René Descartes (

Descartes's

Descartes refused to accept the authority of previous philosophers. He frequently set his views apart from those of his predecessors. In the opening section of the

Many elements of his philosophy have precedents in late

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental

and Descartes were all well-versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.Life

Early life

René du Perron Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine (now

In his book Discourse on the Method, Descartes recalls,

I entirely abandoned the study of letters. Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that of which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth traveling, visiting courts and armies, mixing with people of diverse temperaments and ranks, gathering various experiences, testing myself in the situations which fortune offered me, and at all times reflecting upon whatever came my way so as to derive some profit from it.

Given his ambition to become a professional military officer, in 1618, Descartes joined, as a

While in the service of the

Visions

According to

France

In 1620 Descartes left the army. He visited

Netherlands

Descartes returned to the Dutch Republic in 1628.[27] In April 1629 he joined the University of Franeker, studying under Adriaan Metius, living either with a Catholic family, or renting the Sjaerdemaslot, where he invited in vain a French cook and an optician.[citation needed] The next year, under the name "Poitevin", he enrolled at the Leiden University to study mathematics with Jacobus Golius, who confronted him with Pappus's hexagon theorem, and astronomy with Martin Hortensius.[32] In October 1630 he had a falling-out with Beeckman, whom he accused of plagiarizing some of his ideas. In Amsterdam, he had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine, who was born in 1635 in Deventer.

Unlike many moralists of the time, Descartes was not devoid of passions but rather defended them; he wept upon Francine's death in 1640.[33] "Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man." Russell Shorto postulated that the experience of fatherhood and losing a child formed a turning point in Descartes' work, changing its focus from medicine to a quest for universal answers.[34]

Despite frequent moves,

The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt.

In La Géométrie, Descartes exploited the discoveries he made with Pierre de Fermat, having been able to do so because his paper, Introduction to Loci, was published posthumously in 1679.[38] This later became known as Cartesian Geometry.[38]

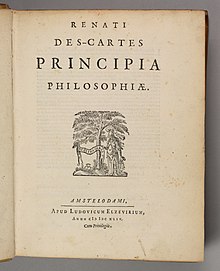

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1641 he published a metaphysics work, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), written in Latin and thus addressed to the learned. It was followed, in 1644, by Principia Philosophiæ (Principles of Philosophy), a kind of synthesis of the Discourse on the Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes was obliged to flee to the Hague, but settled in Egmond-Binnen, where he married his servant Helena (see above) the daughter of the innkeeper.

Descartes began (through Alfonso Polloti, an Italian general in Dutch service) a long correspondence with

Sweden

By 1649, Descartes had become famous throughout Europe for being one of the continent's greatest philosophers and scientists.[37] That year, Queen Christina of Sweden invited Descartes to her court in to organize a new scientific academy and tutor her in his ideas about love. She was interested in and stimulated Descartes to publish the "Passions of the Soul", a work based on his correspondence with Princess Elisabeth.[41] Descartes accepted, and moved to Sweden in the middle of winter.[42]

He was a guest at the house of Pierre Chanut, living on Västerlånggatan, less than 500 meters from Tre Kronor in Stockholm. There, Chanut and Descartes made observations with a Torricellian barometer, a tube with mercury. Challenging Blaise Pascal, Descartes took the first set of barometric readings in Stockholm to see if atmospheric pressure could be used in forecasting the weather.[43][44]

Death

Descartes apparently started giving lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week, at 5 a.m, in her cold and draughty castle. Soon it became clear they did not like each other; she did not like his

In 1996 E. Pies, a German scholar, published a book questioning this account, based on a letter by Johann van Wullen, who had been sent by Christina to treat him, something Descartes refused, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since.]

As a Catholic

Philosophical work

Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker to emphasize the use of reason to develop the

Thus, all Philosophy is like a tree, of which Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk, which are reduced to three principals, namely, Medicine, Mechanics, and Ethics. By the science of Morals, I understand the highest and most perfect which, presupposing an entire knowledge of the other sciences, is the last degree of wisdom.

In his Discourse on the Method, he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as

Descartes built his ideas from scratch. He relates this to architecture: the top soil is taken away to create a new building or structure. Descartes calls his doubt the soil and new knowledge the buildings. To Descartes, Aristotle’s foundationalism is incomplete and his method of doubt enhances foundationalism.[61]

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single principle: thought exists. Thought cannot be separated from me, therefore, I exist (Discourse on the Method and Principles of Philosophy). Most famously, this is known as cogito ergo sum (English: "I think, therefore I am"). Therefore, Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting, therefore the very fact that he doubted proved his existence. "The simple meaning of the phrase is that if one is skeptical of existence, that is in and of itself proof that he does exist."[62]

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been unreliable. So Descartes determines that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is what he does, and his power must come from his essence. Descartes defines "thought" (cogitatio) as "what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it". Thinking is thus every activity of a person of which the person is immediately conscious.[63]

To further demonstrate the limitations of these senses, Descartes proceeds with what is known as the

Therefore, to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he should put aside the senses. He must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

And so something that I thought I was seeing with my eyes is in fact grasped solely by the faculty of judgment which is in my mind.

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding

Descartes also wrote a response to

He gave reasons for thinking that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams, and that one's mind cannot have been "hijacked" by an evil demon placing an illusory external world before one's senses. The Evil Genius Doubt that arises from doubting simple concepts like basic mathematics and geometry. The Evil Genius or evil demon doubt is an external force who is capable of deception.[61]

Three types of ideas

There are three kinds of ideas, Descartes explained: Fabricated, Innate and Adventitious. Fabricated ideas are inventions made by the mind. For example, a person has never eaten moose but assumes it tastes like cow. Adventitious ideas are ideas that cannot be manipulated or changed by the mind. For example, a person stands in a cold room, they can only think of the feeling as cold and nothing else. Innate ideas are set ideas made by God in a person’s mind. For example, the features of a shape can be examined and set aside, but its content can never be manipulated to cause it not to be a three sided object.[64]

Dualism

Descartes, influenced by the Automatons on display throughout the city of Paris, began to investigate the connection between the mind and body.

Descartes suggested that the pineal gland is "the seat of the soul" for several reasons. First, the soul is unitary, and unlike many areas of the brain the pineal gland appeared to be unitary (though subsequent microscopic inspection has revealed it is formed of two hemispheres). Second, Descartes observed that the pineal gland was located near the ventricles. He believed the cerebrospinal fluid of the ventricles acted through the nerves to control the body, and that the pineal gland influenced this process. Sensations delivered by the nerves to the pineal, he believed, caused it to vibrate in some sympathetic manner, which in turn gave rise to the emotions and caused the body to act.[39] Cartesian dualism set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the mind–body problem for many years after Descartes' death.[67]

Descartes denied that animals had reason or intelligence, but did not lack sensations or perceptions, but these could be explained mechanistically.[68] Descartes argued the theory of Innate knowledge and that all humans were born with knowledge through a higher power (religion). It was this theory of Innate knowledge that later led philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) to combat this theory of empiricism (that all knowledge is acquired through experience).[69]

Descartes' moral philosophy

For Descartes, ethics was a science, the highest and most perfect of them. Like the rest of the sciences, ethics had its roots in metaphysics.

Humans should seek the sovereign good that Descartes, following Zeno, identifies with virtue, as this produces a solid blessedness or pleasure. For Epicurus the sovereign good was pleasure, and Descartes says that, in fact, this is not in contradiction with Zeno's teaching, because virtue produces a spiritual pleasure, that is better than bodily pleasure. Regarding Aristotle's opinion that happiness depends on the goods of fortune, Descartes does not deny that this good contributes to happiness but remarks that they are in great proportion outside one's own control, whereas one's mind is under one's complete control.[70]

The moral writings of Descartes came at the last part of his life, but earlier, in his Discourse on the Method he adopted three maxims to be able to act while he put all his ideas into doubt. This is known as his "Provisional Morals".

Religious beliefs

In his Meditations on First Philosophy Descartes sets forth two proofs for God's existence. One of these is founded upon the possibility of thinking the "idea of a being that is supremely perfect and infinite," and suggests that "of all the ideas that are in me, the idea that I have of God is the most true, the most clear and distinct."

Historical impact

Emancipation from Church doctrine

Descartes has often been dubbed the father of modern Western philosophy, the thinker whose approach has profoundly changed the course of Western philosophy and set the basis for

In an

This anthropocentric perspective of Descartes' work, establishing human reason as autonomous, provided the basis for the Enlightenment's emancipation from God and the Church. According to Martin Heidegger, the perspective of Descartes' work also provided the basis for all subsequent anthropology.[82] Descartes' philosophical revolution is sometimes said to have sparked modern anthropocentrism and subjectivism.[11][83][84][85]

Mathematical legacy

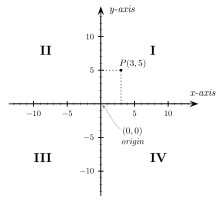

One of Descartes' most enduring legacies was his development of

Descartes' work provided the basis for the calculus developed by Newton and Leibniz, who applied infinitesimal calculus to the tangent line problem, thus permitting the evolution of that branch of modern mathematics.[89] His rule of signs is also a commonly used method to determine the number of positive and negative roots of a polynomial.

Descartes discovered an early form of the law of conservation of mechanical momentum (a measure of the motion of an object), and envisioned it as pertaining to motion in a straight line, as opposed to perfect circular motion, as Galileo had envisioned it. He outlined his views on the universe in his Principles of Philosophy.

Descartes also made contributions to the field of

Influence on Newton's mathematics

Current opinion is that Descartes had the most influence of anyone on the young Newton, and this is arguably one of Descartes' most important contributions. Newton continued Descartes' work on cubic equations, which freed the subject from the fetters of the Greek perspectives. The most important concept was his very modern treatment of independent variables.[92]

Contemporary reception

Although Descartes was well known in academic circles towards the end of his life, the teaching of his works in schools was controversial. Henri de Roy (

Writings

- 1618. Musicae Compendium. A treatise on music theory and the aesthetics of music written for Descartes' early collaborator, Isaac Beeckman (first posthumous edition 1650).

- 1626–1628. Regulae ad directionem ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind). Incomplete. First published posthumously in Dutch translation in 1684 and in the original Latin at Amsterdam in 1701 (R. Des-Cartes Opuscula Posthuma Physica et Mathematica). The best critical edition, which includes the Dutch translation of 1684, is edited by Giovanni Crapulli (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1966).

- 1630–1631. La recherche de la vérité par la lumière naturelle (The Search for Truth) unfinished dialogue published in 1701.

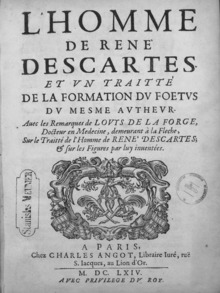

- 1630–1633. Le Monde (The World) and L'Homme (Man). Descartes' first systematic presentation of his natural philosophy. Man was published posthumously in Latin translation in 1662; and The World posthumously in 1664.

- 1637. Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method). An introduction to the Essais, which include the Dioptrique, the Météores and the Géométrie.

- 1637. La Géométrie (Geometry). Descartes' major work in mathematics. There is an English translation by Michael Mahoney (New York: Dover, 1979).

- 1641. Meditationes de prima philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), also known as Metaphysical Meditations. In Latin; a second edition, published the following year, included an additional objection and reply, and a Letter to Dinet. A French translation by the Duke of Luynes, probably done without Descartes' supervision, was published in 1647. Includes six Objections and Replies.

- 1644. Principia philosophiae (Principles of Philosophy), a Latin textbook at first intended by Descartes to replace the Aristotelian textbooks then used in universities. A French translation, Principes de philosophie by Claude Picot, under the supervision of Descartes, appeared in 1647 with a letter-preface to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia.

- 1647. Notae in programma (Comments on a Certain Broadsheet). A reply to Descartes' one-time disciple Henricus Regius.

- 1648. La description du corps humain (The Description of the Human Body). Published posthumously by Clerselier in 1667.

- 1648. Responsiones Renati Des Cartes... (Conversation with Burman). Notes on a Q&A session between Descartes and Frans Burman on 16 April 1648. Rediscovered in 1895 and published for the first time in 1896. An annotated bilingual edition (Latin with French translation), edited by Jean-Marie Beyssade, was published in 1981 (Paris: PUF).

- 1649. Les passions de l'âme (Passions of the Soul). Dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate.

- 1657. Correspondance (three volumes: 1657, 1659, 1667). Published by Descartes' literary executor Claude Clerselier. The third edition, in 1667, was the most complete; Clerselier omitted, however, much of the material pertaining to mathematics.

In January 2010, a previously unknown letter from Descartes, dated 27 May 1641, was found by the Dutch philosopher Erik-Jan Bos when browsing through

See also

- 3587 Descartes, asteroid

- Cartesian circle

- Cartesian diagram

- Cartesian diver

- Cartesian morphism

- Cartesian plane

- Cartesian product

- Cartesian product of graphs

- Cartesian tree

- Conatus (Descartes)

- Descartes' rule of signs

- Descartes' theorem

- Dualistic interactionism

- Folium of Descartes

- Occasionalism

- Paris Descartes University

- Philosophy of Spinoza

- Solipsism

Notes

- ^ Alexander Afriat, "Cartesian and Lagrangian Momentum" (2004).

- The Louvre, Atlas Database

- ISBN 978-0-415-28113-3.

- ^ H. Ben-Yami, Descartes' Philosophical Revolution: A Reassessment, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, p. 76.

- ^ H. Ben-Yami, Descartes' Philosophical Revolution: A Reassessment, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, p. 179: "[Descartes'] work in mathematics was apparently influenced by Vieta's, despite his denial of any acquaintance with the latter’s work."

- Voluntarism. Although there exist doctrinal differences between Descartes and Scotus "it is still possible to view Descartes as borrowing from a Scotist Voluntarist tradition" (see: John Schuster, Descartes-Agonistes: Physcio-mathematics, Method & Corpuscular-Mechanism 1618–33, Springer, 2012, p. 363, fn. 26).

- ^ "She thinks, therefore I am". Columbia Magazine. Fall 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Jacques Bénigne Bossuet, French prelate and historian (1627–1704)" from the Encyclopædia Britannica, 10th Edition (1902)

- ^ "Descartes" entry in Collins English Dictionary, HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

- ^ Colie, Rosalie L. (1957). Light and Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. p. 58.

- ^ a b c Bertrand Russell (2004) History of western philosophy pp.511, 516–7

- ^ Watson, Richard A. (31 March 2012). "René Descartes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ISBN 9780691165752)

- ^ This idea had already been proposed by the Spanish philosopher Gómez Pereira a hundred years ago in the form: "I know I know something. Everything that knows is: thus I am" (Nosco me aliquid noscere: at quidquid noscit, est: ergo ego sum). See: Gómez Pereira, De Inmortalitate Animae, 1749 [1554], p. 277; Santos López, Modesto (1986). "Gómez Pereira, médico y filósofo medinense". In: Historia de Medina del Campo y su Tierra, volumen I: Nacimiento y expansión, ed. by Eufemio Lorenzo Sanz, 1986.

- ISBN 0-205-30840-6.

- ^ R. H. Moorman, "The Influence of Mathematics on the Philosophy of Spinoza", National Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 3. (Dec., 1943), pp. 108–115.

- ^ OCLC 41497065.

- ISBN 978-0-521-36696-0.

- ^ All-history.org

- ^ OCLC 41497065.

- ^ Clarke (2006), p. 24

- ISBN 0006374549.

- ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

- ^ a b c Guy Durandin, Les Principes de la Philosophie. Introduction et notes, Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, Paris, 1970.

- ^ History.mcs.st-and.ac.uk

- ^ Battle of White Mountain, Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ OCLC 41497065.

- ISBN 0-671-01320-3.

- ^ Clarke (2006), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Shea, William R., The Magic of Numbers and Motion, Science History Publications, U.S.A., 1991,

- ^ Nicolas de Villiers, Sieur de Chandoux, Lettres sur l'or potable suivies du traité De la connaissance des vrais principes de la nature et des mélanges et de fragments d'un Commentaire sur l'Amphithéâtre de la Sapience éternelle de Khunrath, Textes édités et présentés par Sylvain Matton avec des études de Xavier Kieft et de Simone Mazauric. Préface de Vincent Carraud, Paris, 2013.

- A.C. Grayling, Descartes: The Life of René Descartes and Its Place in His Times, Simon and Schuster, 2006, pp. 151–152

- ISBN 0-671-01320-3.

- ISBN 978-0-385-51753-9(New York, Random House, October 14th, 2008)

- Utrecht (1635–36), Leiden (1636), Egmond (1636–38), Santpoort (1638–1640), Leiden (1640–41), Endegeest (a castle near Oegstgeest) (1641–43), and finally for an extended time in Egmond-Binnen(1643–49).

- Comenius and Gisbertus Voetiuswere his main opponents.

- ^ OCLC 41497065.

- ^ a b "Pierre de Fermat | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Descartes, René. (2009). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2009 Deluxe Edition. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ISBN 0-8147-0999-0

- ^ The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- OCLC 41497065.

- ^ Islandnet.com

- ^ Archive.org

- OCLC 41497065.

- ^ Rue89.nouvelobs.com

- ^ Severity of winter seasons in the northern Baltic Sea between 1529 and 1990: reconstruction and analysis by S. Jevrejeva, p.6, Table 3

- ^ Pies Е., Der Mordfall Descartes, Solingen, 1996, and Ebert Т., Der rätselhafte Tod des René Descartes, Aschaffenburg, Alibri, 2009. French translation: L'Énigme de la mort de Descartes, Paris, Hermann, 2011

- ^ "Descartes was "poisoned by Catholic priest" – The Guardian, Feb 14 2010". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Was Descartes murdered in Stockholm?". Stockholm News. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[self-published source] - ^ Philosophyonthemesa.com

- ^ a b Rome and the Counter-Reformation in Scandinavia: The Age of Gustavus Adolphus and Queen Christina of Sweden, 1992, p. 510

- ^ a b Descartes: His Life and Thought, 1999, p. 207

- ^ a b Early Modern Philosophy of Religion: The History of Western Philosophy of Religion, 2014, p. 107

- ^ Andrefabre.e-monsite.com

- ^ The remains are, two centuries later, still resting between two other graves–those of the scholarly monks Jean Mabillon and Bernard de Montfaucon—in a chapel of the abbey.

- ^ "5 historical figures whose heads have been stolen". Strange Remains. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^

ISBN 0-19-824250-6..

But contemporary debate has tended to...understand [Cartesian method] merely as the 'method of doubt'...I want to define Descartes' method in broader terms...to trace its impact on the domains of mathematics and physics as well as metaphysics

- ^ a b c Descartes, René. "Letter of the Author to the French Translator of the Principles of Philosophy serving for a preface". Translated by Veitch, John. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ Copenhaver, Rebecca. "Forms of skepticism". Archived from the original on 8 January 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ a b Newman, Lex (1 January 2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ "Ten books: Chosen by Raj Persuade". The British Journal of Psychiatry.

- ^ Descartes, René (1644). The Principles of Philosophy (IX).

- ^ a b "Descartes, Rene | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". www.iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ http://people.whitman.edu/~herbrawt/classes/339/Descartes.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/20013943?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (online): Descartes and the Pineal Gland.

- ^ "Animal Consciousness, No. 2. Historical background". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 23 December 1995. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27532614.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ ISBN 0-8147-0999-0

- ^ Descartes, Rene "Meditations on First Philosophy, 3rd Ed., Translated from Latin by: Donald A. Cress

- ^ Edward C. Mendler, False Truths: The Error of Relying on Authority, p. 16

- ^ Heidegger [1938] (2002), p. 76 quotation:

Descartes... that which he himself founded... modern (and that means, at the same time, Western) metaphysics.

- ^ Schmaltz, Tad M. Radical Cartesianism: The French Reception of Descartes p.27 quotation:

The Descartes most familiar to twentieth-century philosophers is the Descartes of the first two Meditations, someone proccupied with hyperbolic doubt of the material world and the certainty of knowledge of the self that emerges from the famous cogito argument.

- ^ Roy Wood Sellars (1949) Philosophy for the future: the quest of modern materialism quotation:

Husserl has taken Descartes very seriously in a historical as well as in a systematic sense [...] [in The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology, Husserl] finds in the first two Meditations of Descartes a depth which it is difficult to fathom, and which Descartes himself was so little able to appreciate that he let go "the great discovery" he had in his hands.

- ^ Martin Heidegger [1938] (2002) The Age of the World Picture quotation:

For up to Descartes...a particular sub-iectum...lies at the foundation of its own fixed qualities and changing circumstances. The superiority of a sub-iectum...arises out of the claim of man to a...self-supported, unshakeable foundation of truth, in the sense of certainty. Why and how does this claim acquire its decisive authority? The claim originates in that emancipation of man in which he frees himself from obligation to Christian revelational truth and Church doctrine to a legislating for himself that takes its stand upon itself.

- ^ Ingraffia, Brian D. (1995) Postmodern theory and biblical theology: vanquishing God's shadow p.126

- ^ Norman K. Swazo (2002) Crisis theory and world order: Heideggerian reflections pp.97–9

- ^ a b c Lovitt, Tom (1977) introduction to Martin Heidegger's The question concerning technology, and other essays, pp.xxv-xxvi

- ^ Briton, Derek The modern practice of adult education: a postmodern critique p.76

- ^ Martin Heidegger The Word of Nietzsche: God is Dead pp.88–90

- ^ Heidegger [1938] (2002), p. 75 quotation:

With the interpretation of man as subiectum, Descartes creates the metaphysical presupposition for future anthropology of every kind and tendency.

- ^ Benjamin Isadore Schwart China and Other Matters p.95 quotation:

... the kind of anthropocentric subjectivism which has emerged from the Cartesian revolution.

- Charles B. Guignon Heidegger and the problem of knowledgep.23

- Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenologyquotation:

When, with the beginning of modern times, religious belief was becoming more and more externalized as a lifeless convention, men of intellect were lifted by a new belief: their great belief in an autonomous philosophy and science. [...] in philosophy, the Meditations were epoch-making in a quite unique sense, and precisely because of their going back to the pure ego cogito. Descartes work has been used, in fact to inaugurates an entirely new kind of philosophy. Changing its total style, philosophy takes a radical turn: from naïve objectivism to transcendental subjectivism.

- ^ René Descartes, Discourse de la Méthode (Leiden, Netherlands): Jan Maire, 1637, appended book: La Géométrie, book one, page 299. From page 299: " ... Et aa, ou a2, pour multiplier a par soy mesme; Et a3, pour le multiplier encore une fois par a, & ainsi a l'infini ; ... " ( ... and aa, or a2, in order to multiply a by itself; and a3, in order to multiply it once more by a, and thus to infinity ; ... )

- ^ Tom Sorell, Descartes: A Very Short Introduction (2000). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 19.

- ^ Morris Kline, Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times (1972). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 280–281

- ISBN 0-393-04002-X.

- ISBN 0-7167-4389-2.

- ^ "René Descartes". Encarta. Microsoft. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Contemporary Newtonian Research, edited by Z. Bechler, p. 109-129, Newton the Mathematician, by Daniel T. Whiteside, Springer, 1982.

- ^ Cottingham, John, Dugald Murdoch, and Robert Stoothof. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1985. 293.

- ^ Vlasblom, Dirk (25 February 2010). "Unknown letter from Descartes found". Nrc.nl. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Template:Nl" Hoe Descartes in 1641 op andere gedachten kwam – Onbekende brief van Franse filosoof gevonden"

References

Collected works

- Oeuvres de Descartes edited by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery, Paris: Léopold Cerf, 1897–1913, 13 volumes; new revised edition, Paris: Vrin-CNRS, 1964–1974, 11 volumes (the first 5 volumes contains the correspondence). [This edition is traditionally cited with the initials AT (for Adam and Tannery) followed by a volume number in Roman numerals; thus AT VII refers to Oeuvres de Descartes volume 7.]

- Étude du bon sens, La recherche de la vérité et autres écrits de jeunesse (1616–1631) edited by Vincent Carraud and Gilles Olivo, Paris: PUF, 2013.

- Descartes, Œuvres complètes, new edition by Jean-Marie Beyssade and Denis Kambouchner, Paris: Gallimard, published volumes:

- I: Premiers écrits. Règles pour la direction de l'esprit, 2016.

- III: Discours de la Méthode et Essais, 2009.

- VIII.1: Correspondance, 1 edited by Jean-Robert Armogathe, 2013.

- VIII.2: Correspondance, 2 edited by Jean-Robert Armogathe, 2013.

- René Descartes. Opere 1637-1649, Milano, Bompiani, 2009, pp. 2531. Edizione integrale (di prime edizioni) e traduzione italiana a fronte, a cura di G. Belgioioso con la collaborazione di I. Agostini, M. Marrone, M. Savini ISBN 978-88-452-6332-3.

- René Descartes. Opere 1650-2009, Milano, Bompiani, 2009, pp. 1723. Edizione integrale delle opere postume e traduzione italiana a fronte, a cura di G. Belgioioso con la collaborazione di I. Agostini, M. Marrone, M. Savini ISBN 978-88-452-6333-0.

- René Descartes. Tutte le lettere 1619-1650, Milano, Bompiani, 2009 IIa ed., pp. 3104. Nuova edizione integrale dell'epistolario cartesiano con traduzione italiana a fronte, a cura di G. Belgioioso con la collaborazione di I. Agostini, M. Marrone, F. A. Meschini, M. Savini e J.-R. Armogathe ISBN 978-88-452-3422-4.

- René Descartes, Isaac Beeckman, Marin Mersenne. Lettere 1619-1648, Milano, Bompiani, 2015 pp. 1696. Edizione integrale con traduzione italiana a fronte, a cura di Giulia Beglioioso e Jean Robert-Armogathe ISBN 978-88-452-8071-9.

Specific works

- Discours de la methode, 1637

- Renati Des-Cartes Principia philosophiæ, 1644

- Le monde de Mr. Descartes ou le traité de la lumiere, 1664

- Geometria, 1659

- Meditationes de prima philosophia, 1670

- Opera philosophica, 1672

Collected English translations

- 1955. The Philosophical Works, E.S. Haldane and G.R.T. Ross, trans. Dover Publications. This work is traditionally cited with the initials HR (for Haldane and Ross) followed by a volume number in Roman numerals; thus HR II refers to volume 2 of this edition.

- 1988. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes in 3 vols. Cottingham, J., Stoothoff, R., Kenny, A., and Murdoch, D., trans. Cambridge University Press. This work is traditionally cited with the initials CSM (for Cottingham, Stoothoff, and Murdoch) or CSMK (for Cottingham, Stoothoff, Murdoch, and Kenny) followed by a volume number in Roman numeral; thus CSM II refers to volume 2 of this edition.

- 1998. René Descartes: The World and Other Writings. Translated and edited by Stephen Gaukroger. Cambridge University Press. (This consists mainly of scientific writings, on physics, biology, astronomy, optics, etc., which were very influential in the 17th and 18th centuries, but which are routinely omitted or much abridged in modern collections of Descartes' philosophical works.)

Translation of single works

- 1628. Regulae ad directionem ingenii. Rules for the Direction of the Natural Intelligence. A Bilingual Edition of the Cartesian Treatise on Method, ed. and tr. by G. Heffernan, Amsterdam-Atlanta: Rodopi, 1998.

- 1633. The World, or Treatise on Light, tr. by Michael S. Mahoney. http://www.princeton.edu/~hos/mike/texts/descartes/world/worldfr.htm

- 1633. Treatise of Man, tr. by T.S. Hall. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

- 1637. Discourse on the Method, Optics, Geometry and Meteorology, tr. Paul J. Olscamp, Revised edition, Indianapolis: Hackett, 2001.

- 1637. The Geometry of René Descartes, tr. by David E. Smith and M. L. Lantham, New York: Dover, 1954.

- 1641. Meditations on First Philosophy, tr. by J. Cottingham, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Latin original. Alternative English title: Metaphysical Meditations. Includes six Objections and Replies. A second edition published the following year, includes an additional Objection and Reply and a Letter to Dinet. HTML Online Latin-French-English Edition.

- 1644. Principles of Philosophy, tr. by V. R. Miller and R. P. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1983.

- 1648. Descartes' Conversation with Burman, tr. by J. Cottingham, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

- 1649. Passions of the Soul. tr. by S. H. Voss, Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989. Dedicated to Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia.

- 1619-1648. René Descartes, Isaac Beeckman, Marin Mersenne. Lettere 1619-1648, ed. by Giulia Beglioioso and Jean Robert-Armogathe, Milano, Bompiani, 2015 pp. 1696. ISBN 978-88-452-8071-9

Secondary literature

- Agostini, Siegrid; Leblanc, Hélène, eds. (2015). Examina Philosophica. I Quaderni di Alvearium (PDF). Vol. Le fondement de la science. Les dix premières années de la philosophie cartésienne (1619-1628).

- ISBN 0-691-02391-3.

- Carriero, John (2008). Between Two Worlds. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13561-8.

- ISBN 0-521-82301-3.

- Costabel, Pierre (1987). René Descartes – Exercices pour les éléments des solides. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-040099-X.

- ISBN 0-521-36696-8.

- Duncan, Steven M. (2008). The Proof of the External World: Cartesian Theism and the Possibility of Knowledge. Cambridge: James Clarke & Co. ISBN 978-02271-7267-4.

- Farrell, John. "Demons of Descartes and Hobbes." Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau (Cornell UP, 2006), chapter 7.

- Garber, Daniel (1992). Descartes' Metaphysical Physics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-28219-8.

- Garber, Daniel; ISBN 0-521-53721-5.

- ISBN 0-19-823994-7.

- Gillespie, A. (2006). Descartes' demon: A dialogical analysis of 'Meditations on First Philosophy.' Theory & Psychology, 16, 761–781.

- ISBN 0-8027-1501-X.

- Heidegger, Martin [1938] (2002) The Age of the World Picture in Off the beaten track pp. 57–85

- Keeling, S. V. (1968). Descartes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN.

- ISBN 0-19-517510-7.

- Moreno Romo, Juan Carlos, Vindicación del cartesianismo radical, Anthropos, Barcelona, 2010.

- Moreno Romo, Juan Carlos (Coord.), Descartes vivo. Ejercicios de hermenéutica cartesiana, Anthropos, Barcelona, 2007'

- Naaman-Zauderer, Noa (2010). Descartes' Deontological Turn: Reason, Will and Virtue in the Later Writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76330-1.

- Negri, Antonio (2007) The Political Descartes, Verso.

- Ozaki, Makoto (1991). Kartenspiel, oder Kommentar zu den Meditationen des Herrn Descartes. Berlin: Klein Verlag. ISBN 3-927199-01-X.

- Schäfer, Rainer (2006). Zweifel und Sein – Der Ursprung des modernen Selbstbewusstseins in Descartes' cogito. Wuerzburg: Koenigshausen&Neumann. ISBN 3-8260-3202-0.

- Serfati, Michel, 2005, "Géometrie" in Ivor Grattan-Guinness, ed., Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics. Elsevier: 1–22.

- Sorrell, Tom (1987). Descartes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-287636-8.

- Vrooman, Jack Rochford (1970). René Descartes: A Biography. Putnam Press.

- Watson, Richard A. (31 March 2012). "René Descartes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- Watson, Richard A. (2007). Cogito, Ergo Sum: a life of René Descartes. David R Godine. 2002, reprint 2007. ISBN 978-1-56792-335-3. Was chosen by the New York Public library as one of "25 Books to Remember from 2002"

- Woo, B. Hoon (2013). "The Understanding of Gisbertus Voetius and René Descartes on the Relationship of Faith and Reason, and Theology and Philosophy". Westminster Theological Journal. 75 (1): 45–63.

External links

General

- The Correspondence of René Descartes in EMLO

- Works by René Descartes at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about René Descartes at Internet Archive

- Works by René Descartes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Detailed biography of Descartes at MacTutor

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- John Cottingham translation of Meditations and Objections and Replies.

- René Descartes (1596–1650) Published in Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition (1996)

- A site containing Descartes's main works, including correspondence, slightly modified for easier reading

- Descartes Philosophical Writings tr. by Norman Kemp Smith at archive.org

- Studies in the Cartesian philosophy (1902) by Norman Kemp Smith at archive.org

- The Philosophical Works Of Descartes Volume II (1934) at archive.org

- Descartes featured on the 100 French Franc banknote from 1942.

- Free scores by René Descartes at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- René Descartes at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi su Descartes e il Seicento

- Livre Premier, La Géométrie, online and analyzed by A. Warusfel, BibNum[click 'à télécharger' for English analysis]

Bibliographies

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Descartes

- Life and works

- Epistemology

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Ethics

- Modal Metaphysics

- Ontological Argument

- Theory of Ideas

- Pineal Gland

- Law Thesis

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Other