United Kingdom constitutional law

The United Kingdom constitutional law concerns the governance of the

The constitutional principles of

Most constitutional litigation occurs through

History

The history of the UK constitution, though officially beginning in 1800, traces back to a time long before the four nations of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland were fully

Under

While Elizabeth I maintained a Protestant church, under her successor

With

During this time, with the invention of the

From the start of the 20th century, the UK underwent vast social and constitutional change, beginning with an attempt by the

The failed international law system, after

Principles

The British constitution has not been

Parliamentary sovereignty

Parliamentary sovereignty is often seen as a central element in the British constitution, although its extent is contested.

In recent history, four main factors have developed Parliament's sovereignty in practical and legal terms.

Third, the UK became a member of the

Fourth,

It is sometimes the case that parliament pass laws that may be at odds with existing law. In some circumstances new legislation may impliedly repeal parts of existing legislation with courts behaving as the though parts of the old legislation at odds with the new legislation have been repealed. However, parliamentary and court behaviour (notably Thoburn v Sunderland City Council) has suggested the existence of "constitutional legislation" which government must expressly repeal or amend certain pieces of constitutional legislation for the new legislation at odds with the constitutional legislation to apply.[96]

Rule of law

The

At the core of the rule of law, in English and British law, has traditionally been the principle of "

The rule of law also requires law is truly enforced, though enforcement bodies may have room for discretion. In

Democracy

The principle of a "democratic society" is generally seen as a fundamental legitimating factor of both Parliamentary sovereignty and the rule of law. A functioning representative and deliberative democracy, which upholds human rights legitimises the fact of Parliamentary sovereignty,[120] and it is widely considered that "democracy lies at the heart of the concept of the rule of law",[121] because the opposite of arbitrary power exercised by one person is "administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few'".[122] According to the preamble to the European Convention on Human Rights, as drafted by British lawyers following World War II, fundamental human rights and freedoms are themselves "best maintained... by "an effective political democracy".[123] Similarly, this "characteristic principle of democracy" is enshrined by the First Protocol, article 3, which requires the "right to free elections" to "ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature".[124] While there are many conceptions of democracy, such as "direct", "representative" or "deliberative", the dominant view in modern political theory is that democracy requires an active citizenry, not only in electing representatives, but in taking part in political life.[125] Its essence lies not simply majority decision-making, nor referendums that can easily be used as a tool of manipulation,[126] "but in the making of politically responsible decisions" and in "large-scale social changes maximising the freedom" of humankind.[127] The legitimacy of law in a democratic society depends upon a constant process of deliberative discussion and public debate, rather than imposition of decisions.[128] It is also generally agreed that basic standards in political, social and economic rights are necessary to ensure everyone can play a meaningful role in political life.[129] For this reason, the rights to free voting in fair elections and "general welfare in a democratic society" have developed hand-in-hand with all human rights, and form a fundamental cornerstone of international law.[130]

In the UK's "modern democratic constitution",

Internationalism

Like other democratic countries,

Since the World Wars brought an end to the

Regionally, the UK participated in drafting the

Institutions

While principles may the basis of the British constitution, the institutions of the state perform its functions in practice. First,

Parliament

In the British constitution,

Today the

Along with a hereditary monarch, the House of Lords remains an historical curiosity in the British constitution. Traditionally it represented the landed aristocracy, and political allies of the monarch or the government, and has only gradually and incompletely been reformed. Today, the House of Lords Act 1999 has abolished all but 92 hereditary peers, leaving most peers to be "life peers" appointed by the government under the Life Peerages Act 1958, law lords appointed under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876, and Lords Spiritual who are senior clergy of the Church of England.[184] Since 2005, senior judges can only sit and vote in the House of Lords after retirement.[185] The government carries out appointment of most peers, but since 2000 has taken advice from a seven-person House of Lords Appointments Commission with representatives from the Labour, Conservatives and Liberal-Democrat parties.[186] A peerage can always be disclaimed,[187] and ex-peers may then run for Parliament.[188] Since 2015, a peer may be suspended or expelled by the House.[189] In practice the Parliament Act 1949 greatly reduced the House of Lords' power, as can only delay and cannot block legislation by one year, and cannot delay money bills at all.[190] Nevertheless, several options for reform are debated. A House of Lords Reform Bill 2012 proposed to have 360 directly elected members, 90 appointed members, 12 bishops and an uncertain number of ministerial members. The elected Lords would have been elected by proportional representation for 15 year terms, through 10 regional constituencies on a single transferable vote system. However, the government withdrew support after backlash from Conservative backbenches. It has often been argued that if the Lords were elected by geographic constituencies and a party controlled both sides "there would be little prospect of effective scrutiny or revision of government business." A second option, like in Swedish Riksdag, could simply be to abolish the House of Lords: this was in fact done during the English Civil War in 1649, but restored along with the monarchy in 1660. A third proposed option is to elect peers by work and professional groups, so that health care workers elect peers with special health knowledge, people in education elect a fixed number of education experts, legal professionals elect legal representatives, and so on.[191] This is argued to be necessary to improve the quality of legislation.

Judiciary

The judiciary in the United Kingdom has the essential functions of upholding the

The independence of the judiciary is one of the cornerstones of the constitution, and means in practice that judges cannot be dismissed from office. Since the

Executive

The executive branch, while subservient to Parliament and judicial oversight, exercises day to day power of the British government. In form, the UK remains a

Although called the

Although the Prime Minister is the head of Parliament, Her Majesty's Government is formed by a larger group of Members of Parliament, or peers. The "

Public services and enterprise

Public services and enterprise aim to protect the well-being of people in the UK. They create most social and economic rights in practice,

First, the UK does not yet have a "

Fourth among major public services is energy, overseen by the

Regional government

The constitution of British regional governments is an uncodified patchwork of authorities, mayors, councils and devolved government.[278] In Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and London unified district or borough councils have local government powers, and since 1998 to 2006 new regional assemblies or Parliaments exercise extra powers devolved from Westminster. In England, there are 55 unitary authorities in the larger towns (e.g. Bristol, Brighton, Milton Keynes) and 36 metropolitan boroughs (surrounding Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, and Newcastle) which function as unitary local authorities.

In other parts of England, local government is split between two tiers of authority: 32 larger County Councils, and within those 192 District Councils, each sharing different functions. Since 1994, England has had eight regions for administrative purposes at Whitehall, yet these have no regional government or democratic assembly (like in London, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland) after a 2004 referendum on a North East Assembly failed. This means that England has among the most centralised, and disunified systems of governance in the Commonwealth or Europe.

Three main issues in local government are the authorities' financing, their powers, and the reform of governance structures. First, councils raise revenue from

In Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and London there are also regional assemblies and Parliaments, similar to state or provincial governments in other countries. The extent of devolution differs in each place. The

Human rights

Codification of

Although some labelled natural rights as "nonsense upon stilts",

Liberty and a fair trial

The right to

Three main issues of police power and liberty are (1) powers of arrest, detention and questioning, (2) powers to enter, search or seize property, and (3) the accountability of the police for abuse of power. First, the

'The great end, for which men entered into society, was to secure their property. That right is preserved sacred and incommunicable in all instances, where it has not been taken away or abridged by some public law... wherein every man by common consent gives up that right, for the sake of justice and the general good. By the laws of England, every invasion of private property, be it ever so minute, is a trespass. No man can set his foot upon my ground without my licence, but he is liable to an action, though the damage be nothing... If no excuse can be found or produced, the silence of the books is an authority against the defendant, and the plaintiff must have judgment.'

Second, police officers have no right to trespass upon property without a lawful warrant, because as

Privacy

The constitutional importance of privacy, of one's home, belongings, and correspondence, has been recognised since 1604, when

First, the

Third, it has been recognised that the 'right to keep oneself to oneself, to tell other people that certain things are none of their business, is under technological threat' also from private corporations, as well as the state.

Conscience and expression

The rights to freedom of conscience, and freedom of expression, are generally seen as being the 'lifeblood of democracy.'

The practical right to free expression is limited by (1) unaccountable ownership in the media, (2) censorship and obscenity laws, (3) public order offences, and (4) the law of defamation and breach of confidence. First, although anybody can stand on

Second, censorship and obscenity laws have been a highly traditional limit on freedom of expression. The

Association and assembly

The rights to

Like freedom of association,

The right to assembly does not yet extend to private property. In

Social and economic rights

The United Kingdom has historically been at the forefront of guaranteeing social and economic rights through its legislative framework, common law,

Security and intelligence

- article 2(life)

- Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015

- Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011

- Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 s 59

- Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005 s 1

- Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 s 23

- A v Home Secretary[2004] UKHL 56

- A v Home Secretary (No 2) [2005] UKHL 71

- Home Secretary v JJ [2007] UKHL 45

- Home Secretary v AP [2010] UKSC 24

- Gillan v United Kingdom [2009] ECHR 28

- Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 (1928) per Brandeis J 'In a government of laws, existence of the government will be imperiled if it fails to observe the law scrupulously. Our government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. Crime is contagious. If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law; it invites every man to become a law unto himself; it invites anarchy. To declare that in the administration of the criminal law the end justifies the means -- to declare that the government may commit crimes in order to secure the conviction of a private criminal -- would bring terrible retribution.'

Administrative law

Administrative law, through judicial review, is essential to hold executive power and public bodies accountable under the law. In practice, constitutional principles emerge through cases of judicial review, because every public body, whose decisions affect people's lives, is created and bound by law. A person can apply to the High Court to challenge a public body's decision if they have a "sufficient interest",[473] within three months of the grounds of the cause of action becoming known.[474] By contrast, claims against public bodies in tort or contract, where the Limitation Act 1980 usually sets the period as 6 years.[475] Almost any public body, or private bodies exercising public functions,[476] can be the target of judicial review, including a government department, a local council, any Minister, the Prime Minister, or any other body that is created by law. The only public body whose decisions cannot be reviewed is Parliament, when it passes an Act. Otherwise, a claimant can argue that a public body's decision was unlawful in five main types of case:[477]

- it exceeded the lawful power of the body, used its power for an improper purpose, or acted unreasonably,[478]

- it violated a legitimate expectation,[479]

- it failed to exercise relevant and independent judgement,[480]

- it exhibited bias or a conflict of interest, or failed to give a fair hearing,[481] and

- it violated a human right.[482]

As a remedy, a claimant can ask for the public body's decisions to be declared void and quashed (via a quashing order), or it could ask for an order to make the body do something (via a mandatory order), or prevent the body from acting unlawfully (via a prohibiting order). A court may also declare the parties' rights and duties, give an injunction, or compensation could also be payable in tort or contract.[483]

Substantive judicial review

Applications for judicial review are generally divided into claims about the 'substance' of a public body's decision, and claims about the 'procedure' of a decision, although the two overlap, and there is not yet a codified set of grounds as is found in other countries or in other fields of law.

Determining the legality of a public body's action also extends to the purpose and therefore the policy objectives behind the legislation. In

The second major group of cases concern claims that a public body defeated an applicant's 'legitimate expectations'. This is similar to a contract (without the need for consideration) or estoppel, so that if a public body promises or assures somebody something, but does not deliver, they will be able to claim a 'legitimate expectation' was defeated.

Procedural review

As well as reviewing the substance of a decision, judicial review has developed to ensure that public bodies follow lawful and just procedures in making all decisions. First, like the substance of a decision may go beyond the powers of a public body, a procedure actually followed by a public official may not follow what was required by law. In Ridge v Baldwin a chief constable was summarily dismissed by a Brighton police committee, even though the disciplinary regulations made under the Police Act 1919 required an inquiry into charges against someone before they were dismissed. The House of Lords held the regulations applied, and should have been followed, so the dismissal was ultra vires. But in addition, basic principles of natural justice required the constable should have had a hearing before being dismissed. According to Lord Hodson, the 'irreducible minimum' of natural justice is (1) the right to decision by an unbiased tribunal, (2) notice of any charges, and (3) a right to be heard.[502] The same principles with regard to dismissal have been applied to a wide range of public servants, while the law of unfair dismissal and the common law quickly developed to protect the same right to job security.[503]

If statutes are silent, the courts readily apply principles of natural justice, to ensure there is no bias and a fair hearing. These common law principles are reinforced by the

The requirements of a fair hearing are that each side knows the case against them,

Human rights review

Like the common law grounds (that public bodies must act within lawful power, uphold legitimate expectations, and natural justice), human rights violations are a major ground for

Under the

A central difference between judicial review based on human rights, and judicial review based on common law ground that a decision is "

Standing and remedies

Judicial review applications are more limited than other forms of legal claims, particularly those in contract, tort, unjust enrichment or criminal law, although these may be available against public bodies as well. Judicial review applications must be brought promptly, by people with a 'sufficient interest' and only against persons exercising public functions. First, unlike the typical limitation period of six years in contract or tort,[527] the Civil Procedure Rules, rule 54.5 requires that judicial review applications must be made within 'three months after the grounds to make the claim first arose'.[528] Often, however, the same set of facts could be seen as giving rise to concurrent claims for judicial review. In O'Reilly v Mackman prisoners claimed that a prison breached rules of natural justice in deciding they lost the right to remission after a riot. The House of Lords held that, because they had no remedy in 'private law' by itself, and there was merely a 'legitimate expectation' that the prison's statutory obligations would be fulfilled, only a claim for judicial review could be brought, and the three month time limit had expired. It was an abuse of process to attempt a claim in tort for breach of statutory duty.[529]

Second, according to the

A third issue is which bodies are subject to judicial review. This clearly includes any government department, minister, council, or entity set up under a statute to fulfil public functions. However, the division between 'public' and 'private' bodies has become increasingly blurred as more regulatory and public actions have been outsourced to private entities. In R (Datafin plc) v Panel on Take-overs and Mergers the Court of Appeal held that the Takeover Panel, a private association organised by companies and financial institutions in the City of London to enforce standards in takeover bids, was subject to judicial review because it exercised 'immense power de facto by devising, promulgating, amending and interpreting the City Code' with 'sanctions are no less effective because they are applied indirectly and lack a legally enforceable base'.[537] By contrast, the Jockey Club was not thought to exercise sufficient power to be subject to judicial review.[538] Nor was the Aston Cantlow Parochial Church Council, because although a public authority, it was not a 'core' public authority with any significant regulatory function.[539] In a controversial decision, YL v Birmingham CC held that a large private corporation called Southern Cross was not a public authority subject to judicial review, even though it was contracted by the council to run most nursing homes in Birmingham.[540] This decision was immediately reversed by statute,[541] and in R (Weaver) v London and Quadrant Housing Trust the Court of Appeal held that a housing trust, supported by government subsidies, could be subject to judicial review for unjust termination of a tenancy.[542]

Finally, the

See also

- European Union law

- English contract law

- English trusts law

- English land law

- English tort law

- English criminal law

- UK enterprise law

- UK labour law

- UK company law

- Constitutional reform in the United Kingdom

- Ancient constitution of England

Explanatory notes

- ^ Compounded by a ruling in Peacham's Case (1614) that held it would not be treason to advocate the King's death.

- Wilson v United Kingdom[2002] ECHR 552.

- ^ In international law, the duty to stop war propaganda and incitement of discrimination is made explicit.[398]

- The Cambridge Union was established in 1815, and the Oxford Unionin 1823. Most universities have student debating societies.

- ^ Generally the same laws apply to these places of free speech as in the whole country: see Redmond-Bate v DPP [2000] HRLR 249 (Speakers' Corner), Bailey v Williamson (1873) 8 QBD 118 (Hyde Park), and DPP v Haw [2007] EWHC 1931 (Admin).

- ^ In 2019, these were

- YouTube and Google, owned by Alphabet, which is controlled by Larry Page and Sergey Brin

- Facebook, controlled by Mark Zuckerberg, and

- Twitter, controlled by Jack Dorsey.

- ^ In 2019, these were

- the BBC, owned by an arms-length public corporation ultimately accountable to the UK government

- Channel 4, a public corporation set up under the Department for Culture, Media and Sport,

- ITV, owned by asset managers such as Capital Group Companies, Ameriprise Financial and BlackRock

- Channel 5, owned by Viacom Inc, where 80% of votes on shares are controlled by Sumner Redstone, and

- Sky, owned by Comcast which is controlled by Brian L. Roberts.

- ^ In 2019, the largest by website and circulation were

- the Daily Mail and General Trust plc,

- Newscorp,

- the Daily Mirror, Daily Express and Daily Star, controlled by Reach plc

- the Guardian and the Observer, owned by Scott Trust Limited which has a board must guard editorial independence, but which appoints itself,[400]

- the Barclay Brothers, and

- The i, controlled by Alexander Lebedev(who also has a majority stake with Lord Rothermere in the Evening Standard.

- the

- CA 2006 s 168, this becomes the duty in practice, and the culture.[402]

- ^ This is detailed by the Ofcom Broadcasting Code (2017)

- ECHR article 10. cf R v Central Independent Television plc[1994] Fam 192

- ^ Old offences of seditious libel and blasphemous libel were removed by the Criminal Justice and Coroners Act 2009 s 73. See previously R v Burns (1886) 16 Cox CC 355, R v Aldred (1909) 22 Cos CC 1, R v Lemon [1979] AC 617, and Gay News Ltd v UK (1982) 5 EHRR 123 (linking Jesus Christ to homosexuality).

- ^ Trade unions, central and local government appear unable to bring defamation claims: EETPU v Times Newspapers [1980] 1 All ER 1097 (trade unions), Derbyshire CC v Times Newspapers Ltd [1993] AC 534 (local government).

Notes

- ^ Parliament Act 1911 and Parliament Act 1949

- ^ Magna Carta clauses 1 ('... the English church shall be free...'), 12 and 14 (no tax 'unless by common counsel of our kingdom...'), 17 ('Common pleas shall... be held in some fixed place'), 39-40 ('To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice'), 41 ('merchants shall have safe and secure exit from England, and entry to England') and 47-48 (land taken by the King 'shall forthwith be disafforested').

- Maastricht Treaty 1992, succeeding the European Community which the UK joined by the European Communities Act 1972. The WTO was created in 1994.

- ^ See AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) ch 2, 32–48, on historic structure, and devolution.

- FW Maitland, The history of English law before the time of Edward I (1899) Book I, ch I, 1, 'Such is the unity of all history that anyone who endeavours to tell a piece of it must feel that his first sentence tears a seamless web.'

- ^ Pollock and Maitland (1899) 4–5

- (1789) arguing Christianity led to weakness that caused Rome's fall.

- ^ Pollock and Maitland (1899) 5-6

- FW Maitland, The constitutional history of England (1909) 6

- J Froissart, Froissart's Chronicles (1385) translated by GC Macaulay (1895) 251–252.

- ^ DD McGarry, Medieval History and Civilization (1976) 242, 12% free, 30% serfs, 35% bordars and cottars, 9% slaves.

- ^ T Purser, Medieval England, 1042–1228 (2004) 161, this included a 25% tax on income and property, all the year's wool, and all churches gold and silver, to pay a ransom after Richard I was captured when returning from the crusades by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor.

- ^ Magna Carta clauses 12 (Parliament), 17 (court), 39 (fair trial), 41 (free movement), 47 (common land).

- Peasants' revolt of 1381. As ballads and poems evolved, see John Stow, Annales of England (1592)

- Charter of the Forest 1217. This allowed, for example, in clause 9, 'Every freeman shall at his own pleasure provide agistment' or grazing rights, and in clause 12, 'Henceforth every freeman, in his wood or on his land that he has in the forest, may with impunity make a mill, fish-preserve, pond, marl-pit, ditch, or arable in cultivated land outside coverts, provided that no injury is thereby given to any neighbour.'

- ^ Pollock and Maitland (1899) Book I, 173

- The Chronicles of Froissart (1385) translated by GC Macaulay (1895) 250–52, "What have we deserved, or why should we be kept thus in servage? We be all come from one father and one mother, Adam and Eve: whereby can they say or shew that they be greater lords than we be, saving by that they cause us to win and labour for that they dispend? They are clothed in velvet and camlet furred with grise, and we be vestured with poor cloth: they have their wines, spices and good bread, and we have the drawing out of the chaff and drink water: they dwell in fair houses, and we have the pain and travail, rain and wind in the fields; and by that that cometh of our labours they keep and maintain their estates: we be called their bondmen, and without we do readily them service, we be beaten; and we have no sovereign to whom we may complain, nor that will hear us nor do us right."

- A Fitzherbert, Surueyenge(1546) 31, servitude was 'the greatest inconvenience that nowe is suffred by the lawe. That is to have any christen man bounden to an other, and to have the rule of his body, landes, and goodes, that his wyfe, children, and servantes have laboured for, all their life tyme, to be so taken, lyke as it were extorcion or bribery'.

- Utopia(1516) Book I, "wherever it is found that the sheep of any soil yield a softer and richer wool than ordinary, there the nobility and gentry, and even those holy men, the abbots not contented with the old rents which their farms yielded... stop the course of agriculture, destroying houses and towns, reserving only the churches, and enclose grounds that they may lodge their sheep in them... Stop the rich from cornering markets and establishing virtual monopolies. Reduce the number of people who are kept doing nothing. Revive agriculture and the wool industry, so that there is plenty of honest, useful work for the great army of unemployed – by which I mean not only existing thieves, but tramps and idle servants who are bound to become thieves eventually."

- ^ On his behalf Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset ruled as Lord Protector until he was replaced and executed by John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland. Somerset House was transferred to the crown, and Elizabeth was allowed to live there by Mary, Queen of Scots as she killed Lady Jane Grey (1554) and ruled until 1558. Mary then died without children, after killing hundreds of protestants.

- ^ James, The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598)

- Semayne's Case (1604) 5 Coke Rep 91, that nobody can enter another's property without lawful authority and that "the house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well for his defence against injury and violence as for his repose." See also Calvin's Case Calvin's Case (1572) , 77 ER 377that a person born in Scotland is entitled to all rights in England.

- ^ Case of Prohibitions [1607] EWHC J23 (KB)

- ^ a b Case of Proclamations [1610] EWHC KB J22

- ^ (1610) 77 Eng Rep 638

- Marbury v Madison5 US (1 Cranch) 137 (1803).

- ^ (1615) 21 ER 485

- Five Knights' case(1627) 3 How St Tr 1

- Petition of Right 1628 (3 Car 1 c 1)

- )

- ^ Richard Cromwell, Oliver's son, briefly succeeded but lacking support swiftly renounced power after nine months.

- ^ The conflict ended at Battle of the Boyne.

- ^ Bill of Rights 1689 and Claim of Right 1689 arts 2, 8 and 13

- Second Treatise on Government (1689) Chapter IX

- Holt CJconfirmed by the House of Lords.

- Union with Scotland Act 1706 arts 18 and 19, stipulate that Scottish private law would continue under a Scottish court system.

- A Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776) Book V, ch 1, §107

- ^ Keech v Sandford [1726] EWHC J76, an English trust law case following Lord Macclesfield LC, disgraced by his role on the South Sea Company, impeached by the House of Lords and found guilty of taking bribes in 1725. Keech reversed Bromfield v Wytherley (1718) Prec Ch 505 that a fiduciary could take money from a trust and keep profits if they restored the principal afterwards.

- ^ Attorney General v Davy (1741) 26 ER 531 established that any body of assembled people can do a corporate act by a majority.

- ^ Walpole's tenure lasted from 1721-1742.

- ^ Entick v Carrington [1765] EWHC KB J98

- let justice be done whatever be the consequence", held that slavery was "so odious" that nobody could take "a slave by force to be sold" for any "reason whatever".

- ^ AW Blumrosen, 'The Profound Influence in America of Lord Mansfield's Decision in Somerset v Stuart' (2007) 13 Texas Wesleyan Law Review 645

- Transportation Act 1717 and then the Transportation Act 1790.

- Combination Acts, etc.

- J Bentham, Anarchical Fallacies; Being an examination of the Declaration of Rights issued during the French Revolution (1796)

- ^ M Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) Chapter IX

- Union with Ireland Act 1800arts 3–4 gave Irish representation at Westminster.

- T Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) supported this, arguing that working class "vice" and overpopulation was the cause of poverty.

- ^ (1834) 172 ER 1380

- ^ Letter to Lord Russell (October 1862) 'Power in the Hands of the Masses throws the Scum of the Community to the Surface. ... Truth and Justice are soon banished from the Land.'

- Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act 1875 and Allen v Flood[1898] AC 1

- S Tharoor, Inglorious Empire(2018)

- Taff Vale Railway Co v Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants [1901] UKHL 1

- ^ Trade Disputes Act 1906

- ^ Old Age Pensions Act 1908

- ^ Trade Boards Act 1909

- ^ National Insurance Act 1911

- ^ Parliament Act 1949 reduced the power to delay to one year.

- JM Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace(1919)

- ^ a b c e.g. 'Speech to the 69th Annual Conservative Party Conference at Llandudno' (9 October 1948). See J Danzig 'Winston Churchill: A founder of the European Union' (10 November 2013) EU ROPE

- ^ JC Coffee, 'What Went Wrong? An Initial Inquiry into the Causes of the 2008 Financial Crisis' (2009) 9(1) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 1. For problems starting in US regulation, see E Warren, 'Product Safety Regulation as a Model for Financial Services Regulation' (2008) 43(2) Journal of Consumer Affairs 452, and contrast the Consumer Credit Act 1974 or the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Directive 93/13/EEC arts 3–6.

- ^ See AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) chs 1-6

- ^ AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) chs 1-6

- R (Miller) v Prime Minister [2019] UKSC 41, [39]

- Act of Union 1707. The European Communities Act 1972, the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Constitutional Reform Act 2005may now be added to this list."

- ^ On conventions, see Attorney General v Jonathan Cape Ltd [1975] 3 All ER 484

- T Bingham, The Rule of Law (2011) and Entick v Carrington [1765] EWHC KB J98

- University constituencies, and the Representation of the People Act 1969 lowered the voting age to 18. Restrictions on prisoner voting were inserted by the Representation of the People Act 1983. British citizens abroad can vote under the Representation of the People Act 1985, but millions of UK residents, who pay taxes but do not have citizenship, cannot vote.

- Appropriation Act 1923Sch 4

- AW Bradley, 'The Sovereignty of Parliament – Form or Substance?' in J Jowell, The Changing Constitution (7th edn 2011) ch 2

- ^ cf AW Bradley and KD Ewing, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2015) 65, it 'is not possible to predict the outcome of changes made by Parliament to the 'manner and form' of the legislative process since, depending on the nature and reasons for such changes, the courts might still be influenced by a deep-seated belief in the proposition that Parliament cannot bind itself.'

- ^ Magna Carta cl 12, 'No scutage [tax on knight's land or fee] nor aid shall be imposed on our kingdom, unless by common counsel of our kingdom...'

- ^ Earl of Oxford's case (1615) 21 ER 485, Lord Ellesmere LC, '... when a Judgment is obtained by Oppression, Wrong and a hard Conscience, the Chancellor will frustrate and set it aside, not for any error or Defect in the Judgment, but for the hard Conscience of the Party.'

- Dr Bonham's case(1610) 8 Co Rep 114a

- ^ Parliament Act 1949 s 1.

- ^ Parliament Act 1911 s 1.

- ^ [2005] UKHL 56, [120] 'Parliamentary sovereignty is an empty principle if legislation is passed which is so absurd or so unacceptable that the populace at large refuses to recognise it as law'.

- ^ See also a photo of the first General Assembly.

- ^ cf Leslie Stephen, The Science of Ethics (1882) 145, "Lawyers are apt to speak as though the legislature were omnipotent, as they do not require to go beyond its decisions. It is, of course, omnipotent in the sense that it can make whatever laws it pleases, inasmuch as a law means any rule which has been made by the legislature. But from the scientific point of view, the power of the legislature is of course strictly limited. It is limited, so to speak, both from within and from without; from within, because the legislature is the product of a certain social condition, and determined by whatever determines the society; and from without, because the power of imposing laws is dependent upon the instinct of subordination, which is itself limited. If a legislature decided that all blue-eyed babies should be murdered, the preservation of blue-eyed babies would be illegal; but legislators must go mad before they could pass such a law, and subjects be idiotic before they could submit to it."

- AV Dicey, The Law of the Constitution (1885) 39-40, Parliament has 'under the English constitution, the right to make or unmake any law whatever; and further... no person or body is recognised by the law of England as having a right to override or set aside the legislation of Parliament.'

- Treaty of Versailles 1919 Part XIII, statute of the International Labour Organization

- ^ See the International Organisations Act 1968 ss 1-8

- ^ United Nations Act 1946 s 1

- ^ See, for example, the Legality of the Iraq War page.

- ^ Treaty on European Union Article 2

- ^ Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen (1963) Case 26/62, [94] member states "have limited their sovereign rights, albeit within limited fields, and have thus created a body of law which binds both their nationals and themselves" on the "basis of reciprocity".

- ^ [1990] UKHL 7

- ^ [1990] UKHL 7

- ^ [2014] UKSC 3

- Re Wünsche Handelsgesellschaft(22 October 1986) BVerfGE, [1987] 3 CMLR 225

- ^ [2017] UKSC 5

- ^ See Opinion polling for the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum#Post–referendum polling

- ^ [2017] UKSC 5, [146] "Judges, therefore, are neither the parents nor the guardians of political conventions; they are merely observers. As such, they can recognise the operation of a political convention in the context of deciding a legal question (as in the Crossman diaries case - Attorney General v Jonathan Cape Ltd [1976] 1 QB 752), but they cannot give legal rulings on its operation or scope, because those matters are determined within the political world. As Professor Colin Munro has stated, "the validity of conventions cannot be the subject of proceedings in a court of law" - (1975) 91 LQR 218, 228."

- R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the EU [2017] UKSC 5, [43] "Parliamentary sovereignty is a fundamental principle of the UK constitution" and at [50] "it is a fundamental principle of the UK constitution that, unless primary legislation permits it, the Royal prerogative does not enable ministers to change statute law or common law... This is, of course, just as true in relation to Scottish, Welsh or Northern Irish law."

- ISBN 978-0-9928904-2-1.

- ^ cf Aristotle, Politics (330 BCE) 3.16, 'It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens'.

- ^ X v Morgan-Grampian Ltd [1991] AC 1, 48, per Lord Bridge, 'The maintenance of the rule of law is in every way as important in a free society as the democratic franchise. In our society the rule of law rests upon twin foundations: the sovereignty of the Queen in Parliament in making the law and the sovereignty of the Queen's courts in interpreting and applying the law.'

- ^ R (Jackson) v Attorney General [2005] UKHL 56, [104] per Lord Hope

- ^ King's College, Londonalso remarked, 'democracy lies at the heart of the concept of the rule of law'.

- AV Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (3rd edn 1889) Part II, ch IV, 189, first "absolute supremacy or predominance of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power", second "equality before the law, or the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by the ordinary law courts" and third, "principles of private law have with us been by the action of the courts and Parliament so extended as to determine the position of the Crown and of its servants". See also J Raz, 'The Rule of Law and its Virtue' (1977) 93 Law Quarterly Review 195. Contrast D Lino, 'The Rule of Law and the Rule of Empire: A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context' (2018) 81(5) Modern Law Review 739. Previously, discourse among international finance followed a restrictive ideal: M Stephenson, 'Rule of Law as a Goal of Development Policy' (2008) World Bank Research

- ^ Constitutional Reform Act 2005 ss 1, 63-65 and Schs 8 and 12

- ^ Entick v Carrington [1765] EWHC KB J98

- ^ Malone v United Kingdom (1984) 7 EHRR 14

- T Bingham, Rule of Law (2008) 8, 'all persons and authorities within the state, whether publicor private should be bound by and entitled to the benefit of laws publicly made, taking effect (generally) in the future and publicly administered in the courts.'

- ^ [1765] EWHC KB J98

- ^ European Convention on Human Rights Article 8 (1) Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence. (2) There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others."

- ^ [1979] Ch 344

- ^ [1984] ECHR 10, (1984) 7 EHRR 14

- ^ Originally the Interception of Communications Act 1985, and now the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 ss 1-11, as amended by the Data Retention and Investigatory Powers Act 2014.

- ^ [2008] UKHL 60, [2]-[7]

- ^ R (Corner House Research) v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2008] UKHL 60, [55]

- A v Home Secretary[2004] UKHL 56, Lord Nicholls, 'indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial is anathema in any country which observes the rule of law'.

- ^ [2017] UKSC 51, [66]-[68]

- ^ e.g. M v Home Office [1993] UKHL 5, holding the Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker, in contempt of court for failing to return a Zaire teacher to the UK on refugee status, despite a High Court judge ordering it be done.

- The Spirit of the Laws(1748) Book XI, ch 6, 'When legislative power is united with executive power in a single person or in a single body of the magistracy, there is no liberty.'

- W Bagehot, The English Constitution 65, the 'efficient secret' of the UK constitution was 'the close union, the nearly complete fusion, of the legislative and executive powers'.

- ^ Constitutional Reform Act 2005 ss 108-9

- ^ Constitutional Reform Act 2005 s 3.

- AV Dicey, The Law of the Constitution (10th edn 1959) 73, who said 'The electors in the long run can always enforce their will', on the basis that executive dominance over Parliament might require revisions of the extent of the concept.

- Reference on Quebec (1998) 161 DLR (4th) 385, 416, "democracy in any real sense of the word cannot exist without the rule of law." R (UNISON) v Lord Chancellor[2017] UKSC 51, [68] "Without such access [to courts], laws are liable to become a dead letter, the work done by Parliament may be rendered nugatory, and the democratic election of Members of Parliament may become a meaningless charade."

- ^ See Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (c 411 BC) Book 2, para 37. Contrast Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book V, Parts 3 and 4, translated by DP Chase (favouring aristocracy, by equating it with appointment according "excellence", supposedly), and Plato, The Republic, Book IV, Part V, 139, translated by D Lee (arguing that philosopher kings should rule over a rigid hierarchy where there was "no interchange of jobs").

- ECHR 1950 Preamble

- ECHR 1950 Prot 1, art 3

- A Lincoln, Gettysburg Address(1863) "that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth".

- ^ cf AJ Zurcher, 'The Hitler Referenda' (1935) 29(1) American Political Science Review 91

- FL Neumann, The Democratic and the Authoritarian State (1957) 186-193

- J Habermas, Between Facts and Norms (1996) 135, 'the only law that counts as legitimate is one that could be rationally accepted by all citizens in a discursive process of opinion- and will-formation.'

- R Dworkin, 'Constitutionalism and Democracy' (1995) 3(1) European Journal of Philosophy 2-11, 4-5, a constitutional democracy means: (1) 'a majority or plurality of people' (2) 'all citizens have the moral independence necessary to participate in the political decision as free moral agents' (3) 'the political process is such as to treat all citizens with equal concern'. D Feldman, Civil Liberties and Human Rights in England and Wales (2002) 32-33 'it would be perverse to argue that there is anything undemocratic about a restriction on the capacity of decision-makers to interfere with the rights which are fundamental to democracy itself'. See also Matadeen v Pointu[1999] 1 AC 98, Lord Hoffmann, "Their Lordships do not doubt that such a principle [of equality] is one of the building blocks of democracy and necessarily permeates any democratic constitution."

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966, Article 4

- ^ Archie v Law Association of Trinidad and Tobago [2018] UKPC 23, [18] Lady Hale, "A vital element in any modern democratic constitution is the independence of the judiciary from the other arms of government, the executive and the legislature. This is crucial to maintaining the rule of law: the judges must be free to interpret and apply the law, in accordance with their judicial oaths, not only in disputes between private persons but also in disputes between private persons and the state. The state, in the shape of the executive, is as much subject to the rule of law as are private persons." cf KD Ewing, 'The Resilience of the Political Constitution' [2013] 14(12) German Law Journal 2111 Archived 30 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 2116, suggesting the current political constitution of the UK is not necessarily the same as a fully democratic constitution.

- ^ (1703) 2 Ld Raym 938, dissent approved by the House of Lords.

- ^ [1975] QB 151

- ^ Animal Defenders International v United Kingdom [2008] UKHL 15, [48] and see also [2013] ECHR 362

- ^ Gorringe v Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council [2004] UKHL 15, [2]. See also O'Rourke v Camden London Borough Council [1998] AC 188, "the [Housing] Act [1985] is a scheme of social welfare, intended to confer benefits at the public expense on grounds of public policy."

- Johnson v Unisys Limited [2001] UKHL 13, and Gisda Cyf v Barratt[2010] UKSC 41, [39]

- Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundation v Council and Commission(2008) C-402/05, holding that international law binds EU law unless it requires an act that would run contrary to basic human rights.

- ^ e.g. Magna Carta, ch 41, 'All merchants shall have safe and secure exit from England, and entry to England, with the right to tarry there and to move about as well by land as by water, for buying and selling by the ancient and right customs, quit from all evil tolls, except (in time of war) such merchants as are of the land at war with us...'

- ^ Coke, 1 Institutes 182

- Shipmoney Act 1640, and after the civil war and glorious revolution, once again by the Bill of Rights 1689art 4.

- ^ Lethulier's Case (1692) 2 Salk 443, "we take notice of the laws of merchants that are general, not of those that are particular."

- ^ Luke v Lyde (1759) 97 Eng Rep 614, 618; (1759) 2 Burr 882, 887

- ^ Pillans v Van Mierop (1765) 3 Burr 1663

- ^ Somerset v Stewart (1772) 98 ER 499, "The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of now being introduced by Courts of Justice upon mere reasoning or inferences from any principles, natural or political; it must take its rise from positive law; the origin of it can in no country or age be traced back to any other source: immemorial usage preserves the memory of positive law long after all traces of the occasion; reason, authority, and time of its introduction are lost..."

- ^ Saad v SS for the Home Department [2001] EWCA Civ 2008, [15] Lord Phillips MR, quoting Bennion on Statutory Interpretation (3rd ed) p 630 that: "It is a principle of legal policy that the municipal law should conform to public international law. The court, when considering, in relation to the facts of the instant case, which of the opposing constructions of the enactment would give effect to the legislative intention, should presume that the legislator intended to observe this principle."

- Lord Hoffmann

- ^ [2014] UKSC 47

- Lord Kerr, dissenting, at [247]-[257] argued the dualist theory of international law should be abandoned, and international law should be directly effective in UK law.

- Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundation v Council and Commission(2008) C-402/05

- ^ See the Venice Commission, Code of Practice on Referendums (2007) on asking questions with concrete, determinative choices.

- ^ e.g. Winston Churchill, 'Speech to the 69th Annual Conservative Party Conference at Llandudno' (9 October 1948). See J Danzig 'Winston Churchill: A founder of the European Union' (10 November 2013) EU ROPE

- ^ cf World Trade Organization (Immunities and Privileges) Order 1995

- ^ On the post-referendum crisis, see R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2017] UKSC 5 and European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 s 1, giving power to the PM to notify intention to negotiate to leave the EU.

- ^ The Parliament Act 1911 set elections to take place at a maximum of each five years, but elections usually occurred in a fourth year. Before this the maximum was seven years, but in practice governments called votes sooner.

- ^ Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 s 1(3). By contrast, Australia has elections each 3 years, and the US has presidential elections each 4 years.

- ^ Parliament Act 1911 and Parliament Act 1949.

- ^ Life Peerages Act 1958 s 1

- ^ House of Lords Act 1999 ss 1-2, or 90 plus the "Lord Great Chamberlain" and the "Earl Marshal".

- Lord Hoffmann

- Acts of Supremacy 1534, the Earl of Oxford's case (1615) 21 ER 485, and the Bill of Rights 1689

- ^ This was represented by the Parliament Act 1911, following the People's Budget of 1909.

- JS Mill, Considerations on Representative Government (1861) ch 5. AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) ch 8.

- ^ HC Modernisation Committee (2001-2) HC 1168, recommended publishing draft bills, and (2005-6) HC 1097, 'one of the most successful Parliamentary innovations of the last ten years' and 'should become more widespread'.

- ^ Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 s 1(3)

- ^ Mental Health Act 1983 or Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964

- ^ See Hirst v United Kingdom (No 2) [2005] ECHR 681 (blanket disqualification of convicted prisoners from voting breached ECHR Prot 1, art 3. After this the UK failed to change its laws. Green v United Kingdom [2010] ECHR 868 reaffirmed the position. HL Paper 103, HC 924 (2013-14) recommended prisoners serving under 12 months should be entitled to vote. Parliament still did not act. McHugh v UK [2015] ECHR 155, reaffirmed breach but awarded no compensation or costs.However, Moohan v Lord Advocate [2014] UKSC 67 and Moohan v UK (13 June 2017) App No 22962/15, denial of prisoner voting in the Scottish independent referendum was not a breach of art 3.

- ^ Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 ss 1-5

- ^ (1703) 2 Ld Raym 938

- ^ Morgan v Simpson [1975] QB 151, per Lord Denning MR

- ^ cf R (Wilson) v Prime Minister [2018] EWHC 3520 (Admin) Archived 16 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, and E McGaughey, 'Could Brexit be Void?' (2018) King's Law Journal

- PPERA 2000ss 72-131 and Schs 8-13, in referendums, the limit has traditionally been set at £600,000 for the official campaigns on each side.

- ^ Communications Act 2003 ss 319-333.

- Baroness Hale. Confirmed in [2013] ECHR 362.

- ^ Representation of the People Act 1983 ss 92. Furthermore, any "trading" with hostile foreign parties with whom the UK is "at war" may lead to seven years in prison. Trading with the Enemy Act 1939 (c 89) ss 1-2, seven years prison for trading with an enemy who is "at war with His majesty".

- ^ R (Electoral Commission) v City of Westminster Magistrate's Court and UKIP [2010] UKSC 40, holding that a partial forfeiture of £349,216 donations by a non-UK resident was appropriate.

- ^ Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 ss 12-69 and 149

- ^ Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, setting up the Boundary Commission. See also, R (McWhirter) v Home Secretary (21 October 1969) The Times, elector in Enfield sought mandamus ('we command') to require Home Secretary to perform statutory duty of laying before Parliament Commission reports with draft orders in Council.

- ^ Electoral Administration Act 2006 s 17

- ^ Act of Settlement 1700 s 3 unless 'qualifying Commonwealth and Irish citizens, British Nationality Act 1981 Sch 7 and Electoral Administration Act 2006 s 18

- ^ Insolvency Act 1986 s 426A(5)

- ^ RPA 1983 ss 160 and 173

- House of Commons Disqualification Act 1957 ss 1 and 5 and House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975give further exceptions.

- ^ Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975 ss 1-2

- ^ House of Lords Act 1999 ss 1-2

- ^ Constitutional Reform Act 2005 s 24

- ^ See the Lords Appointments webpage.

- ^ Now confirmed in the House of Lords Reform Act 2014

- ^ Peerages Act 1963 and Re Parliamentary Election for Bristol South East [1964] 2 QB 257, Viscount Stansgate or Tony Benn challenged the law disqualifying peers standing for Parliament.

- ^ House of Lords (Expulsion and Suspension) Act 2015

- ^ Parliament Act 1911 ss 1-3 and Parliament Act 1949

- ^ cf GDH Cole, Self-Government in Industry (5th edn 1920) ch V, 134-135. S Webb, Reform of the House of Lords (1917) Fabian Tract No. 183, 7, at 12, preferring a chamber of around 100 people elected by proportional representation. E McGaughey, 'A Twelve Point Plan for Labour, and A Manifesto for Labour Law' (2017) 46(1) Industrial Law Journal 169 Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Practice Statement [1966] 3 All ER 77

- ^ Employment Tribunals Act 1996, appealing to the Employment Appeal Tribunal.

- ^ Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, appealing to the appropriate Upper Tribunal division.

- ^ e.g. Hounga v Allen [2014] UKSC 47

- McCulloch v Maryland(1819) 17 US (4 Wheat) 316

- ^ See Re Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] UKHL 41.

- ^ See Pickin v British Railways Board [1974] AC 765

- Lord Hoffmann, "In this way the courts of the United Kingdom, though acknowledging the sovereignty of Parliament, apply principles of constitutionality little different from those which exist in countries where the power of the legislature is expressly limited by a constitutional document."

- ^ Inquiries Act 2005

- ^ See now the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 s 33 and Senior Courts Act 1981 s 11(3)

- ^ AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2014) 329, 'whatever the theoretical position, there are a number of reasons which help to ensure that these latter powers are unlikely ever to be used, with the security of judicial tenure relying not so much on legal rules as on a shared constitutional understanding which these rules reflect.'

- ^ Codified in 1963, updated in 1972 and 2001, HC Deb (15 December 2001) col 1012.

- ^ Constitutional Reform Act 2005 s 3

- ^ Courts and Legal Services Act 1990

- CRA 2005 s 27A and SI 2013/2193. See also Judicial Appointments Regulations 2013(SI 2192)

- CRA 2005ss 70-79

- ^ cf 'Baroness Brenda Hale: "I often ask myself 'why am I here?'" (17 September 2010) Guardian "I'm quite embarrassed to be the only justice to tick a lot of the diversity boxes, for example the gender one, the subject areas in which I'm interested (which are not ones that most of my colleagues have had much to do with up until now), the fact that I went to a non-fee-paying school and the fact that I wasn't a practitioner for any great length of time. I'm different from most of my colleagues in a number of respects (and they're probably at least as conscious of this as I am). I think we could do with more of that sort of diversity."

- ^ [2017] UKSC 51

- ^ See the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985

- ^ See R Blackburn, 'Monarchy and the personal prerogatives' [2004] Public Law 546, explaining that the "personal prerogative" of the monarch is a set of powers that must be exercised according to law, and must follow the advice of the prime minister, or in accordance with Parliament and the courts.

- US Declaration of Independencein 1776.

- W Bagehot, The English Constitution (1867) 111, suggesting the monarch has a right to be consulted, to encourage and to warn.

- ^ The Sunday Times Rich List 2015 estimated the Queen's personal wealth at £340 million, making her the 302nd richest person in the UK: H Nianias, 'The Queen drops off the top end of the Sunday Times Rich List for the first time since its inception' (26 April 2015) The Independent

- ^ Sovereign Grant Act 2011 ss 1-6. This was raised from 15% by SI 2017/438 art 2.

- Crown Estate Act 1961s 1, up to eight Crown Estate Commissioners are appointed by the monarch on PM advice.

- ^ 'Crown Estate makes record £304m Treasury payout' (28 June 2016) BBC News. See map.whoownsengland.org and the colour purple for the Crown Estate. This includes (1) retail property such as Regent Street in London, commercial property in Oxford, Milton Keynes, Nottingham, Newcastle, etc., and a right to receive 23% of the income from the Duchy of Lancaster's Savoy Estate in London (2) 116,000 hectares of agricultural land and forests, together with minerals and residential and commercial property (3) rights to extract minerals covers some 115,500 hectares (4) 55% of the UK's foreshore, and all of the UK's seabed from mean low water to the 12-nautical-mile (22 km) limit, plus sovereign rights of the UK in the seabed and its resources vested by the Continental Shelf Act 1964.

- I Jennings, Cabinet Government (3rd edn 1959) ch 2

- ^ Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011

- ^ The vote was 45.13% in favour of becoming a republic, but on a model of having a directly elected president. 54..87% of voters opposed this. See [2000] Public Law 3.

- Coke CJ, "true it was, that God had endowed His Majesty with excellent science, and great endowments of nature; but His Majesty was not learned in the laws of his realm of England, and causes which concern the life, or inheritance, or goods, or fortunes of his subjects".

- R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the EU[2017] UKSC 5

- ^ cf AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) ch 10 258-265, listing 9 categories.

- ^ HC Deb (21 April 1993) col 490 and HC 422 (2003-4) Treasury Solicitor, suggesting an exhaustive catalogue of powers is probably not possible, but listing major categories.

- ^ Subject to the Life Peerages Act 1958 and House of Lords Act 1999 s 1

- R v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, ex p Bancoult (No 2)[2008] UKHL 61, [69] per Lord Bingham

- R (FBU) v Home Secretary [1995] 2 AC 513, Re Lord Bishop of Natal(1864) 3 Moo PC (NS) 115

- Criminal Appeal Act 1995s 16

- ^ e.g. the Island of Rockall was seized in 1955, and later recognised in the Island of Rockall Act 1972. See R (Lye) v Kent JJ [1967] 2 QB 153 on alterations.

- ^ Nissan v AG [1970] AC 179, now regulated by Immigration Act 1971 s 33(5). The power of expulsion is considered 'doubtful' outside statute: AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) ch 10, 261

- ^ Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 s 20, codifying the previous Ponsonby Rule.

- ^ Burmah Oil Co Ltd v Lord Advocate [1965] AC 75, 101

- ^ This convention was established through the Iraq war, where Parliament backed an invasion contrary to international law in 2003, and a vote against an invasion of Syria in 2013.

- ^ Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart NV v Administrator of Hungarian Property [1954] AC 584

- ^ e.g. MoJ, Rev of the Exec Royal Prer Powers (2009) 23

- ^ Spook Erection Ltd v Environment Secretary [1989] QB 300 (beneficiary of market franchise not entitled to Crown's exemption from planning control)

- ^ e.g. Butler v Freeman (1756) Amb 302, In re a Local Authority [2003] EWHC 2746, Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417.

- ^ Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1985] AC 374

- Chevening Estate Act 1959, Ministerial and other Pensions and Salaries Act 1991

- ^ Ministers of the Crown Act 1975 s 5. Under the Crown Proceedings Act 1947 s 17 the Minister for Civil Service (i.e. the PM) maintains a list of govt departments (for the purpose of proceedings against the Crown).

- AG v Jonathan Cape Ltd[1976] QB 752, suggesting the duty of confidentiality expires after a number of years out of government.

- ^ Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 s 3, putting management of the civil service into statute. Civil Service Management Code s 11.1.1, civil servants employed at pleasure of the Crown, theoretically lacking a wrongful dismissal remedy according to somewhat outdated case law: Dunn v R [1896] 1 QB 116 and Riordan v War Office [1959] 1 WLR 1046, but under the Employment Rights Act 1996 s 191, civil servants expressly have the right to claim unfair dismissal.

- ^ Freedom of Information Act 2000 ss 1 and 21-44. Sch 1 lists public bodies that are subject. The BBC can only be required to disclose information held for non-journalistic purposes, to protect freedom of expression: Sugar v BBC [2012] UKSC 4 and BBC v Information Commissioner [2009] UKHL 9

- ^ E McGaughey, Principles of Enterprise Law: the Economic Constitution and Human Rights (Cambridge UP 2022) ch 2(4) and chs 8-20

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966art 6 (full employment), art 11 (food, housing), art 12 (medical care), art 13 (free education, including higher education), art 15(1)(b) ("benefits of scientific progress")

- ^ Bill of Rights 1689 clause 4, ‘levying money... without grant of Parliament... is illegal’. Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005 s 11 (HMRC under Treasury control)

- ^ J Portes, H Reed, A Percy, Social prosperity for the future: A proposal for Universal Basic Services (2017)

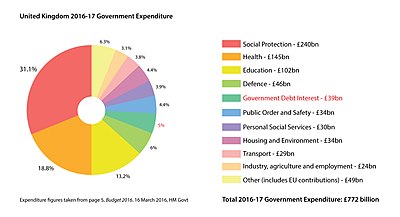

- ^ "Budget 2016" (PDF). HM Treasury. March 2016. p. 5.

- ^ A Simon et al, 'Acquisitions, Mergers and Debt: the new language of childcare' (January 2022) UCL

- ^ Department for Education, 'Free childcare: How we are tackling the cost of childcare' (7 July 2023) gov.uk

- ^ The Public Schools Act 1868 regulated Eton, Harrow, Charterhouse, Rugby, Shrewsbury and Westminster, and the Education Act 1996 s 463, defines an ‘independent’ school as "not a school maintained by a local authority".

- ^ Education Act 2002 s 19, but numbers of staff and council representatives cut in 2011 by EA 2011 s 38

- ^ Higher Education and Research Act 2017 Sch 9, para 2

- ^ University of Cambridge, Statute A.IV.1., Oxford University, Statute VI, arts. 4 and 13; Council Regulation 13 of 2002, regs. 4–10, Higher Education Governance (Scotland) Act 2016

- ^ Education Reform Act 1988 s 124A and Sch 7A, para 3

- ^ National Health Service Act 2006 section 43(2A) (2% to 49%), inserted by HSCA 2012, sections 164 and 165. National Health Service (Private Finance) Act 1997 s 1

- NHS Act 2006ss 1H (NHS England), and 3 (ICBs that "commission" services of hospitals)

- NHS Act 2006 Sch. 7, paras. 3 and 9

- Bank of England Act 1998Sch 1, paras 1–2

- BEA 1998 s 13 and Sch 3, paras. 10–13, on the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank. E McGaughey, Principles of Enterprise Law (2022) ch 10, 380-8

- ^ Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 establishes the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority. See also the Consumer Credit Act 1974

- ^ Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992 sets rates for the state pension, while occupational pensions are regulated by the Pensions Act 2008, Pensions Act 2004, and Pensions Act 1995

- ^ Petroleum Act 1998 s 9A

- Domestic Gas and Electricity (Tariff Cap) Act 2018ss 1-3

- ^ Electricity Act 1989 ss 3A-10O, 16-23, 32-47, Sch 6 and Energy Act 2011 ss 94-102 and Standard Electricity Supply Licence, conditions 7-10

- ^ Housing Act 1985 s 24 (abolishing fair rent rules)

- ^ Agriculture Act 2020 s 1

- ^ Water Act 1989 ss 4, 83-85

- ^ S Hendry, Frameworks for Water Law Reform (2014) ch 5

- Highways England

- ^ Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 ss 15-16, Sch 1 (ORR constitution)

- ^ Railways Act 1993 s 25 and Bus Services Act 2017 s 22

- ^ Office of Communications Act 2002 s 1

- ^ Communications Act 2003 ss 1-5, 17, 147-151, 185-192, 232-240

- ^ Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006 ss 1-14, 20-35

- ^ Defence (Transfer of Functions) Act 1964 and Armed Forces Act 2006 ss 12, 19, 42, 155-164, 334-9

- ^ Greater London Authority Act 1999 ss 31, 141, 180 and 333 (with highly limited powers except in transport)

- S Webb, English Local Government (1929) Volumes I–X.

- ^ See Greater London Authority Act 1999 ss 31, 141, 180 and 333 (with highly limited powers except in transport) the Scotland Act 1998 ss 28-29 and Sch 5 (with full legislative power except 'reserved matters'), the Government of Wales Act 2006 Sch 5 (setting a list of devolved 'fields'), and the Northern Ireland Act 1998 s 4 and Schs 2 and 3 (listing excepted and reserved matters, but the Assembly can legislate in all other fields).

- ^ Local Government Finance Act 1992 set up property value bands, but despite proposals in 1995, these have never been altered despite drastic shifts in house prices.

- ^ Local Government Finance Act 1992 ss 52ZA-ZY, introduced by the Localism Act 2011. Also under ss 52A-Y in Wales the Secretary can cap council tax if deemed excessive.

- ^ N Amin-Smith and D Phillips, 'English council funding: what's happened and what's next?' (2019) IFS, BN 250 Archived 3 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See further Local Government Finance Act 1992 ss 65-68. Council Tax (Administration and Enforcement) Regulations 1992 regs 8-31

- ^ See DCLG duties and other duties.

- ^ Localism Act 2011 ss 1-5, which add that the Secretary of State can remove restrictions through secondary legislation.

- ^ Town and Country Planning Act 1990 ss 65-223

- ^ Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 ss 13-39

- ^ Education Act 1996 ss 3A-458

- ^ Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964 ss 1-13

- ^ Childcare Act 2006 ss 6-13

- ^ Highways Act 1980 ss 25-31A

- NHS and Community Care Act 1990 ss 46-47. Carers and Disabled Children Act 2000s 1-6A

- ^ Environmental Protection Act 1990 ss 45-73A

- ^ e.g. Household Recycling Act 2003

- ^ Building Act 1984 ss 59-106

- ^ eg Housing Act 1985 ss 8-43 and 166-8

- ^ cf Widdicombe Committee, Committee of Inquiry into the Conduct of Local Authority Business (1986) Cmnd 9797

- ^ Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 s 107A and Sch 5A

- ^ Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016 s 15. cf M Elliot, Public Law (2016) 320, 'The net result, over time, will be a patchwork of combined authorities with elected mayors, supplying a mezzanine layer of government that sits between individual local authorities and central government.' HC 369 (2015-16) [53] criticised the lack of actual public consultation in creating combined authorities. See also 2012 English mayoral referendums and List of lord mayoralties and lord provostships in the United Kingdom.

- ^ cf Sir Kenneth Calman Report, Serving Scotland Better (2009)

- ^ Belfast or Good Friday Agreement (10 April 1998)

- ^ Government of Wales Act 2006 Sch 5 listing (1) agriculture, fisheries, forestry and rural development) (2) ancient monuments and historic buildings (3) culture (4) economic development (5) education and training (6) environment (7) fire and rescue services and promotion of fire safety (8) food (9) health and health services (10) highways and transport (11) housing (12) local government (13) National Assembly for Wales (14) public administration (15) social welfare (16) sport and recreation (17) tourism (18) town and country planning (19) water and flood defence (20) Welsh language.

- ^ See Agricultural Sector (Wales) Bill - Reference by the Attorney General for England and Wales [2014] UKSC 43

- ^ Eleanor Roosevelt: Address to the United Nations General Assembly 10 December 1948 in Paris, France

- Petition of Right 1628 reasserted these values from Magna Carta against King Charles I.

- J Bentham, Anarchical Fallacies; Being an Examination of the Declarations of Rights Issued During the French Revolution (1789) art II

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (1792). See also O de Gouges, Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen(1791)

- Second Reform Act 1867 and the Trade Union Act 1871.

- jus cogens norms in international law, since two treaties, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rightsof 1966 recast the UDHR.

- Re Wünsche Handelsgesellschaft(22 October 1986) BVerfGE 73, 339 (first setting out the basic concepts).

- ^ ECHR arts 2 (right to life). Article 3 (right against torture). Article 4, right against forced labour, see Somerset v Stewart (1772) 98 ER 499. Articles 12-14 are the right to marriage, effectiveness and to equal treatment.

- ^ ECHR arts 5-11.

- ^ Magna Carta ch XXIX, 'NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.'

- article 4. See also the Habeas Corpus Act 1679 and Bird v Jones(1845) 7 QB 742.

- ^ cf Benjamin Franklin, Objections to Barclay's Draft Articles of February 16 (1775) 'They who can give up essential Liberty to obtain a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.'

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 arts 9-16

- ^ ECHR art 5(1)

- ^ ECHR art 5(2)-(5)

- ^ AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) 398, 'Every power conferred on police officers inevitably means a corresponding reduction in the liberty of the individual, and brings us face to face with Convention obligations.'

- ^ Home Affairs Committee, Policing in the 21st Century (2007-8) HC 364-I, para 67, the UK spent 2.5% of GDP on police, the OECD's highest.

- ^ Police Reform Act 2002 s 40

- PACEA 1984ss 1 and 117

- PACEA 1984s 2, and s 3 requires details are recorded.

- ^ Home Office Code A, para 2.2B(b). The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 s 23 enables stop and search powers for unlawful drugs. M Townsend, 'Racial bias in police stop and search getting worse, report reveals' (13 October 2018) Guardian, finds black people are 9 times more likely than white people to be searched. In 2019, 43% of searches in London were on black people: (26 January 2019) Guardian. See also K Rawlinson, 'Bristol race relations adviser Tasered by police is targeted again' (19 October 2018) Guardian.

- ^ Jackson v Stevenson (1879) 2 Adam 255, per the Lord Justice General

- ^ Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 s 60(5) and see B Bowling and E Marks, 'The rise and fall of suspicionless searches' (2017) 28 KLJ 62.

- ^ R (Roberts) v MPC [2015] UKSC 79.

- PACEA 1984s 24

- ^ Alanov v Sussex CC [2012] EWCA Civ 235, 'the "threshold" for the existence of "reasonable grounds" for suspicion is low... small, even sparse.' Also R (TL) v Surrey CC [2017] EWHC 129

- ^ Magistrates' Courts Act 1980 s 1 and 125D-126. nb Constables' Protection Act 1750 s 6 means a constable who arrests someone in good faith is protected from liability from arrest if it turns out the warrant was beyond the jurisdiction of the person who issued it.

- PACEA 1984 s 24A

- PACEA 1984 s 28. Hill v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire [1990] 1 All ER 1046, s 28 is a rule 'laid down by Parliament to protect the individual against the excess or abuse of the power of arrest'. Christie v Leachinsky[1947] AC 573, 'the arrested man is entitled to be told what is the act for which he is arrested.'

- PACEA 1984ss 30-39

- PACEA 1984ss 41-45ZA.

- PACEA 1984 ss 54-58 and Terrorism Act 2000 s 41 and Sch 8 para 9. Ibrahim v UK [2016] ECHR 750, suggests that damages were recoverable for denial of access to a solicitor in breach of Convention rights. cf Cullen v Chief Constable of the RUC[2003] UKHL 39, held there was no right to damages for failure to permit legal representatives, but evidence may be inadmissible.

- PACEA 1984ss 60-64A.

- ^ Condron v UK (2000) 31 EHRR 1, 20 the right to silence is in ECHR art 6, 'at the heart'. But drawing adverse inferences is not an infringement.

- ^ Beckles v UK (2003) 36 EHRR 162

- PACEA 1984ss 76-78.

- ^ Brown v Stott [2001] 1 AC 681, on the Road Traffic Act 1988

- PACEA 1984 ss 9-14 and Sch 1, paras 4-12. See R v Singleton(1995) 1 Cr App R 431.

- ^ Thomas v Sawkins [1935] 2 KB 249, power to enter to stop breach of peace: controversial. KD Ewing and C Gearty, The Struggle for Civil Liberties (2000) ch 6.

- ^ McLeod v UK (1998) 27 EHRR 493

- PACEA 1984ss 19 and 21, a record must be provided to the occupier, and a person has a right of access under police supervision unless this would prejudice investigation.

- Woolf LJ

- ^ Police Act 1996 s 89

- ^ R v Iqbal [2011] EWCA Crim 273

- ^ Police Act 1996 s 88, Police Reform Act 2002 s 42 and Kuddus v Chief Constable of Leicestershire Constabulary [2001] UKHL 29

- PACEA 1984 ss 76-78 and see R v Khan [1997] AC 558, an illegally placed surveillance device evidence was admissible, even with probable ECHR art 8 breach, but merely 'a consideration which may be taken into account for what it is worth'. Schenck v Switzerland (1988) 13 EHRR 242, irregularly obtained evidence can be admitted. R v Loosely[2001] UKHL 53, no need to change s 78 for the ECHR.

- ^ Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 s 1

- ^ Police Act 1996 ss 37A-54

- ^ e.g. R v MPC ex p Blackburn (No 3) [1973] QB 241

- Hill v CC of West Yorkshire[1989] AC 53

- Osman v UK (2000) 29 EHRR 245, ECHR art 2 requires the state 'to take preventive operational measures to protect an individual whose life is at risk from the criminal acts of another individual.' But breach hard to establish. DSD v MPC[2018] UKSC 11

- ^ Semayne's case (1604) 77 Eng Rep 194, Sir Edward Coke, 'The house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well for his defence against injury and violence as for his repose.'

- ECHR article 8

- ^ (1765) 19 St Tr 1030

- ^ Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 explanatory notes stated over 1300 statutory provisions enable entry into people's homes, and while ss 39-47 and Sch 2 enable a Minister to repeal and replace these powers, the government continued to add them, e.g. Scrap Metal Dealers Act 2013 s 16(1)

- ^ See AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) ch 16, 429, not just the state but private parties violate privacy, highlighting 'newspapers engaged in a desperate circulation war, or employers checking on employees'. S Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (2019)

- ECHR article 8.

- ^ Police Act 1997 s 104

- RIPA 2000ss 26-36.

- ^ Investigatory Powers Tribunal, Report 2010 (2011) 28.

- ^ R v Barkshire [2011] EWCA Crim 1885.

- ^ [2012] UKSC 62, [21] Lord Hope, 'He took the risk of being seen and of his movements being noted down. The criminal nature of what he was doing, if that was what it was found to be, was not an aspect of his private life that he was entitled to keep private.'

- ^ Investigatory Powers Act 2016 ss 6 and 20

- IPA 2016ss 19 and 23

- IPA 2016s 26

- IPA 2016s 56

- ^ Privacy International v Foreign Secretary [2016] UKIPTrib 15_110-CH

- ^ a b House of Commons, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, Disinformation and 'fake news': Final Report (2019) HC 1791

- Lord Hoffmann

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union 2000 art 8

- GDPR 2016arts 5-6

- GDPR 2016arts 6-7

- ^ See the Consumer Rights Act 2015 at present.

- GDPR 2016 arts 12-14

- GDPR 2016art 17. Also art 18 gives the right to restrict processing.

- GDPR 2016 art 20

- ^ [2012] UKSC 55

- ^ House of Commons, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, Disinformation and 'fake news': Final Report (2019) HC 1791, [150] and [255]-[256]

- GDPR 2016art 83.

- ^ S and Marper [2008] ECHR 1581, limits to retain DNA information

- ^ Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 s 27(4) and National Police Records (Recordable Offences) Regulations 2000/1139, recording people's convictions, cautions, reprimands, and warnings for any offence punishable with prison or in the Schedule.

- ^ [2009] UKSC 3

- ^ cf J Kollewe, 'NHS data is worth billions – but who should have access to it?' (10 June 2019) Guardian and S Boseley, 'NHS to scrap single database of patients' medical details' (6 July 2016) Guardian

- ^ Prince Albert v Strange (1849) 1 Mac&G 25

- ^ R (Ingenious Media Holdings plc) v HMRC [2016] UKSC 54 and Campbell v MGN Ltd [2004] UKHL 22, [14] per Lord Nicholls, and [2005] UKHL 61

- ^ Associated Newspapers Ltd v Prince of Wales [2006] EWCA Civ 1776

- ^ PJS v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2016] UKSC 26, [32]

- ^ R v Home Secretary, ex p Simms [2000] 2 AC 115, 126

- ^ Plato, Crito (ca 350 BC) and JS Mill, On Liberty (1859) ch 1

- ^ Book of Matthew 26-27. Book of John 18. Book of Luke 23.

- ^ R v Penn and Mead or Bushell's case (1670) 6 St Tr 951, prosecuting Quakers under the Religion Act 1592 (offence to not attend church) and the Conventicle Act 1664 and Conventicles Act 1670 (prohibitions on religious gatherings over five people outside the Church of England).

- Unlawful Oaths Act 1797.

- ^ Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, and contrast the Gordon Riots following the Papists Act 1778.

- Redfearn v Serco Ltd [2012] ECHR 1878

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 Articles 18-20

- Leveson Report(2012-13) HC 779 discussing media concentration and competition.

- ^ "article 63" (PDF).