Crown of the Kingdom of Poland

Crown of the Kingdom of Poland Korona Królestwa Polskiego ( Latin ) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1385–1795 | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: " May 3 Constitution | 3 May 1791 | ||||||||||||

| 7 January 1795 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

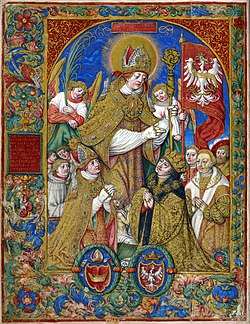

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland (

The idea of the Crown in Central Europe first appeared in Bohemia and Hungary, from where the model was taken by kings

The development of the concept of corona regni in Poland

External influences

The concept of corona regni first emerged in early 12th-century

For Poland, the significant development was the emergence of the concept of corona regni in Hungary in the late 12th century. Initially, it represented the kingdom as a territorial entity linked to the

In Bohemia, the concept of the corona regni emerged primarily in connection with the territorial expansion and consolidation of the state. The

Idea of the Kingdom

The history of Poland as an entity has been traditionally traced to c. 966, when the

A special role was played by

In 1295, the Duke of Greater Poland Przemysł II, although his power did not extend to Kraków, and was crowned king in

Casimir, like his father, considered himself the inherent ruler of the kingdom, the heir of the ancient Bolesławs. He strove to extend his power over the remaining Piast princes and to regain all the lands ruled by the former kings of Poland.

The king, however, regarded himself as a patrimonial ruler who could freely manage the kingdom and its lands.

Idea of the Crown

The concept of Corona Regni appears in the documents of Casimir the Great only three times, and all three documents were produced by foreign chanceries in the king's name. This idea, which limited the monarch's power, gained popularity only after his death. The annulment of Casimir the Great's testament in 1370 was essentially the first act undertaken in the name of the interests of the Crown. Ludwik was initially inclined to recognize the will, but strong opposition forced him to refer the matter to the court, which ruled that the ruler could not diminish the territory of the Crown of the Kingdom, a decision that Ludwik accepted.[5] Similarly, the new king, Louis the Great, committed himself to reclaiming the lost territories not for himself, but for the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, during his coronation.[6][5] Jan Radlica was the first royal chancellor who stopped referring to himself as "of Kraków" or "of the court" chancellor and began to use in 1381 the title regni Poloniae supremus cancellarius (supreme chancellor of the Kingdom of Poland).[5]

The concept of the Crown being the real sovereign began to be promoted by the elites of Lesser Poland, who saw it as a way to elevate their role. This was facilitated by the rule of a foreign king, the regency in Poland by his mother,

The interregnum following the death of Ludwik in 1382, which ended with the coronation of Jadwiga in 1384, was evidence of the vitality of the Crown of the Kingdom. During this period, the magnates (regnicolae regni Poloniae) managed the affairs of the state, avoiding a bloody civil war and successfully leading to the coronation of new ruler.[26] Moreover, the basis of power began to rest on an agreement between the dynasty and the kingdom's community. The nobles respected the natural right of Louis's daughters to the throne, but this right was conditional upon adherence to the oaths and obligations made by the ruler to the Crown of the Kingdom.[27]

Union of Krewo

The

The union concluded at Krewo was not an ordinary personal union, common in Europe at that time, precisely because one party was the Corona Regni, that is, the community of the Kingdom of Poland, and not a dynasty or ruler, as was the case with the agreement between

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin created the single state of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth on July 1, 1569 with a real union between the Crown and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Before then, the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania only had a personal union. The Union of Lublin also made the Crown an elective monarchy; this ended the Jagiellonian dynasty once Henry de Valois was elected on May 16, 1573 as monarch.

On May 30, 1574, two months after Henry de Valois was crowned King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania on February 22, 1574, he was made King of France, and was crowned King of France on February 13, 1575. He left the throne of the Crown on May 12, 1575, two months after he was crowned King of France. Anna Jagiellon was elected after him.

Constitution of 1791

The Constitution of May 3, 1791 is the second-oldest, codified national constitution in history, and the oldest codified national constitution in Europe; the oldest being the

It made Poland a constitutional monarchy with the King as the head of the executive branch with his

The Government Act angered

Politics

The creation of the Crown of the

A related concept that evolved soon afterward was that of

Geography

The concept of the Crown also had geographical aspects, particularly related to the indivisibility of the Polish Crown's territory.

At the same time, the Crown also referred to all lands that the Polish state (not the monarch) could claim to have the right to rule over, including those that were not within Polish borders.[45]

The term distinguishes those territories federated with the

Prior to the 1569

During that period, a term for a Pole from the Crown territory was koroniarz (plural: koroniarze) – or Crownlander(s) in English – derived from Korona – the Crown.

Depending on context, the Polish "Crown" may also refer to "

Provinces

After the Union of Lublin (1569) Crown lands were divided into two provinces: Lesser Poland (Polish: Małopolska) and Greater Poland (Polish: Wielkopolska). These were further divided into administrative units known as voivodeships (the Polish names of the voivodships and towns are shown below in parentheses).

Greater Poland Province

- Brześć Kujawski Voivodeship (województwo brzesko-kujawskie, Brześć Kujawski)

- Gniezno Voivodeship (województwo gnieźnieńskie, Gniezno) from 1768

- Inowrocław Voivodeship (województwo inowrocławskie, Inowrocław)

- Kalisz Voivodeship (województwo kaliskie, Kalisz)

- Łęczyca Voivodeship (województwo łęczyckie, Łęczyca)

- Mazowsze, Warsaw)

- Poznań Voivodeship (województwo poznańskie, Poznań)

- Płock Voivodeship (województwo płockie, Płock)

- Podlaskie Voivodeship (województwo podlaskie, Drohiczyn)

- Rawa Voivodeship (województwo rawskie, Rawa)

- Sieradz Voivodeship (województwo sieradzkie, Sieradz)

- Prince-Bishopric of Warmia

Lesser Poland Province

- Bełz)

- Bracław Voivodeship (województwo bracławskie, Bracław)

- Czernihów Voivodeship (województwo czernihowskie, Czernihów)

- Kijów Voivodeship (województwo kijowskie, Kijów)

- Kraków Voivodeship (województwo krakowskie, Kraków)

- Lublin Voivodeship (województwo lubelskie, Lublin)

- Kamieniec Podolski)

- Lwów)

- Sandomierz Voivodeship (województwo sandomierskie, Sandomierz)

- Łuck)

- Duchy of Siewierz (Siewierz)

Royal Prussia Province (1569–1772)

Royal Prussia (Polish: Prusy Królewskie) was a semi-autonomous province of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1772. Royal Prussia included Pomerelia, Chełmno Land (Kulmerland), Malbork Voivodeship (Marienburg), Gdańsk (Danzig), Toruń (Thorn), and Elbląg (Elbing). Polish historian Henryk Wisner writes that Royal Prussia belonged to the Province of Greater Poland.[46]

Other holdings or fiefs

Principality of Moldavia (1387–1497)

The history of Moldavia has long been intertwined with that of Poland. The Polish chronicler Jan Długosz mentioned Moldavians (under the name Wallachians) as having joined a military expedition in 1342, under King Władysław I, against the Margraviate of Brandenburg.[47] The Polish state was powerful enough to counter the Hungarian Kingdom which was consistently interested in bringing the area that would become Moldavia into its political orbit.

Ties between Poland and Moldavia expanded after the Polish

Although

The principality of Moldavia covered the entire geographic region of Moldavia. In various periods, various other territories were politically connected with the Moldavian principality. This is the case of the province of

) or, at a later date, the territories between the Dniester and the Bug rivers.Towns in Spisz (Szepes) County (1412–1795)

As one of the terms of the

Duchy of Siewierz (1443–1795)

Prince-Bishopric of Warmia (1466–1772)

The Prince-Bishopric of Warmia

Lauenburg and Bütow Land

After the childless death of the last of the

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (Courland) (1562–1791)

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia is a

Duchy of Prussia (1569–1657)

The Duchy of Prussia was a

Duchy of Livonia (Inflanty) (1569–1772)

The Duchy of Livonia[55] was a territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – and later a joint domain (Condominium) of the Polish Crown and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Protectorates

Caffa

In 1462, during the expansion of the

See also

- Administrative division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen

- Lands of the Crown of Saint Wenceslaus

Notes

- ^ "Gaude Mater Polonia Creation and History". Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ISBN 9780199253395.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e Frost 2015, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Szczur 2002, p. 417.

- ^ Frost 2015, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, p. 24.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, pp. 27–31.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, p. 31.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, p. 38.

- ^ Dąbrowski 1956, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 317.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 317-318.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 318-319.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 331-343.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 414.

- ^ a b c Szczur 2002, p. 416.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 372.

- ^ a b Szczur 2002, p. 415.

- ^ Szczur 2002, p. 401.

- ^ Borkowska, Urszula (2011). Dynastia Jagiellonów w Polsce. p. 309.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 14-15.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 15-17.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 49.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 33.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 50.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 51-53.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 51-55.

- ^ Frost 2015, p. 56-57.

- ^ Henry Smith Williams (1904). The Historians' History of the World: Poland, The Balkans, Turkey, Minor eastern states, China, Japan. Outlook Company. pp. 88–91. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-307-38773-8. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 978-90-481-2400-8. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- JSTOR 564654.

- ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-4411-4812-4. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-881284-09-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, pp. 85–86

- ^ Henryk Wisner, Rzeczpospolita Wazów. Czasy Zygmunta III i Władysława IV. Wydawnictwo Neriton, Instytut Historii PAN, Warszawa 2002, p. 26 [ISBN missing]

- ^ The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 273

- ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9.

- ^ Zygmunt Gloger Geografia historyczna ziem dawnej Polski "Właściwą Małopolskę stanowiły województwa: Krakowskie, Sandomierskie i Lubelskie, oraz kupione (w wieku XV) przez Zbigniewa Oleśnickiego, biskupa krakowskiego, u książąt śląskich księstwo Siewierskie"

- ISBN 978-0-8006-7085-6.

- ^ Biskupie Księstwo Warmińskie @ Google books

- ISBN 978-0-521-85332-3.

- ^ Translation of a treaty between the King of Prussia and the King and Republic of Poland. In: The Scots Magazine, vol. XXXV, Edinburgh 1773, pp. 687–691.

- ISBN 83-223-1984-3

- ISBN 90-6550-881-3, p 17

- ^ Historia Polski Średniowiecze, Stanisław Szczur, Kraków 2002, s. 537.

References

- Dąbrowski, Jan (1956). Korona Królestwa Polskiego w XIV wieku. Studium z dziejów rozwoju polskiej monarchii stanowej (in Polish). Zakład im. Ossolińskich.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820869-3.

- Jan Herburt, Statuta Regni Poloniae: in ordinem alphabeti digesta, Cracoviae (Kraków) 1563.

- Henryk Litwin, Central European Superpower, BUM Magazine, October 2016.

- Szczur, Stanisław (2002). Historia Polski. Średniowiecze. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. ISBN 978-83-08-03272-5.,