Endometrium

| Endometrium | |

|---|---|

fallopian tubes (uterine tubes). (Endometrium labeled at center right.) | |

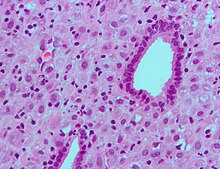

Endometrium in the proliferative phase | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Uterus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica mucosa uteri |

| MeSH | D004717 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.027 |

| TA2 | 3521 |

| FMA | 17742 |

| Anatomical terminology] | |

The endometrium is the inner epithelial layer, along with its mucous membrane, of the mammalian uterus. It has a basal layer and a functional layer: the basal layer contains stem cells which regenerate the functional layer.[1] The functional layer thickens and then is shed during menstruation in humans and some other mammals, including other apes, Old World monkeys, some species of bat, the elephant shrew[2] and the Cairo spiny mouse.[3] In most other mammals, the endometrium is reabsorbed in the estrous cycle. During pregnancy, the glands and blood vessels in the endometrium further increase in size and number. Vascular spaces fuse and become interconnected, forming the placenta, which supplies oxygen and nutrition to the embryo and fetus.[4][5] The speculated presence of an endometrial microbiota[6] has been argued against.[7][8]

Structure

The endometrium consists of a single layer of

- The functional layer is adjacent to the uterine cavity. This layer is built up after the end of menstruation during the first part of the previous menstrual cycle. Proliferation is induced by estrogen (follicular phase of menstrual cycle), and later changes in this layer are engendered by progesterone from the corpus luteum (luteal phase). It is adapted to provide an optimum environment for the implantation and growth of the embryo. This layer is completely shed during menstruation.

- The basal layer, adjacent to the myometrium and below the functional layer, is not shed at any time during the menstrual cycle. It contains stem cells that regenerate the functional layer,[1] which develops on top of it.

In the absence of progesterone, the arteries supplying blood to the functional layer constrict, so that cells in that layer become

It is possible to identify the phase of the menstrual cycle by reference to either the ovarian cycle or the uterine cycle by observing microscopic differences at each phase—for example in the ovarian cycle:

| Phase | Days | Thickness | Epithelium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual phase | 1–5 | Thin | Absent |

| Follicular phase | 5–14 | Intermediate | Columnar |

| Luteal phase | 15–27 | Thick | Columnar. Also visible are arcuate vessels of uterus |

Ischemic phase |

27–28 | Columnar. Also visible are arcuate vessels of uterus |

Gene and protein expression

About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and some 70% of these genes are expressed in the normal endometrium.

Microbiome speculation

The uterus and endometrium was for a long time thought to be sterile. The

The normal dominance of Lactobacilli in the vagina is seen as a marker for vaginal health. However, in the uterus this much lower population is seen as invasive in a closed environment that is highly regulated by female sex hormones, and that could have unwanted consequences. In studies of

Function

The endometrium is the innermost lining layer of the

During pregnancy, the glands and blood vessels in the endometrium further increase in size and number. Vascular spaces fuse and become interconnected, forming the placenta, which supplies oxygen and nutrition to the embryo and fetus.

Cycle

The functional layer of the endometrial lining undergoes cyclic regeneration from stem cells in the basal layer.[1] Humans, apes, and some other species display the menstrual cycle, whereas most other mammals are subject to an estrous cycle.[2] In both cases, the endometrium initially proliferates under the influence of estrogen. However, once ovulation occurs, the ovary (specifically the corpus luteum) will produce much larger amounts of progesterone. This changes the proliferative pattern of the endometrium to a secretory lining. Eventually, the secretory lining provides a hospitable environment for one or more blastocysts.

Upon fertilization, the egg may implant into the uterine wall and provide feedback to the body with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). hCG provides continued feedback throughout pregnancy by maintaining the corpus luteum, which will continue its role of releasing progesterone and estrogen. In case of implantation, the endometrial lining remains as decidua. The decidua becomes part of the placenta; it provides support and protection for the gestation.

Without implantation of a fertilized egg, the endometrial lining is either reabsorbed (estrous cycle) or shed (menstrual cycle). In the latter case, the process of shedding involves the breaking down of the lining, the tearing of small connective blood vessels, and the loss of the tissue and blood that had constituted it through the vagina. The entire process occurs over a period of several days. Menstruation may be accompanied by a series of uterine contractions; these help expel the menstrual endometrium.

If there is inadequate stimulation of the lining, due to lack of hormones, the endometrium remains thin and inactive. In humans, this will result in

In humans, the cycle of building and shedding the endometrial lining lasts an average of 28 days. The endometrium develops at different rates in different mammals. Various factors including the seasons, climate, and stress can affect its development. The endometrium itself produces certain hormones at different stages of the cycle and this affects other parts of the reproductive system.

(A) proliferative endometrium (Left: HE × 400) and proliferative endometrial cells (Right: HE × 100)

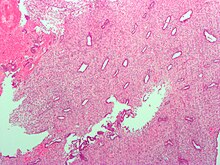

(B) secretory endometrium (Left: HE × 10) and secretory endometrial cells (Right: HE × 10)

(C) atrophic endometrium (Left: HE × 10) and atrophic endometrial cells (Right: HE × 10)

(D) mixed endometrium (Left: HE × 10) and mixed endometrial cells (Right: HE × 10)

(E): endometrial atypical hyperplasia (Left: HE × 10) and endometrial atypical cells (Right: HE × 200)

(F) endometrial carcinoma (Left: HE × 400) and endometrial cancer cells (Right: HE × 400).

- Adenomyosis is the growth of the endometrium into the muscle layer of the uterus (the myometrium).

- Endometriosis is the growth of tissue similar to the endometrium, outside the uterus.[16]

- Endometrial hyperplasia

- Endometrial cancer is the most common cancer of the human female genital tract.

- adhesions, occurs when the basal layer of the endometrium is damaged by instrumentation (e.g., D&C) or infection (e.g., endometrial tuberculosis) resulting in endometrial sclerosis and adhesion formation partially or completely obliterating the uterine cavity.

Thin endometrium may be defined as an endometrial thickness of less than 8 mm. It usually occurs after

Embryo transfer

An endometrial thickness (EMT) of less than 7 mm decreases the pregnancy rate in

Observation of the endometrium by

Endometrial thickness is also associated with live births in IVF. The live birth rate in a normal endometrium is halved when the thickness is <5mm.[23]

Endometrial protection

Estrogens stimulate endometrial

Additional images

-

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma from biopsy. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph of decidualized endometrium due to exogenous progesterone. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph of decidualized endometrium due to exogenous progesterone. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph showing endometrial stromal condensation, a finding seen inmenses.

See also

- CYTL1, also known as cytokine-like like protein 1.

- Endometrial ablation

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

- ^ PMID 19228591.

- ^ PMID 22057551.

- S2CID 196624853.

- ^ a b Blue Histology - Female Reproductive System Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. School of Anatomy and Human Biology — The University of Western Australia Accessed 20061228 20:35

- ^ ISBN 9780721602400.

- PMID 26597628.

- ^ PMID 29552006.

- ^ PMID 28454555.

- ^ "The human proteome in endometrium - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- S2CID 802377.

- PMID 26488136.

- ^ "Dictionary - Normal: Endometrium - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- PMID 8426860.

- ^ William's Gynecology, McGraw 2008, Chapter 8, Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

- S2CID 26249687.

- PMID 31717614.

- PMID 19200982.

- PMID 19328470.

- PMID 23619009.

- PMID 24664156.

- PMID 23190428.

- PMID 15343603.

- ^ 1. Gallos, I. D. et al. Optimal endometrial thickness to maximize live births and minimize pregnancy losses: Analysis of 25,767 fresh embryo transfers. Reprod. Biomed. Online 37, 542–548 (2018).

- ^ PMID 20870686.

- ^ S2CID 24616324.

- ^ S2CID 244749616.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 43:05-15 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The uterus, uterine tubes and ovary with associated structures."

- Histology image: 18902loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Female Reproductive System uterus, endometrium"

- UB, and UF) gnidation/role02

- Histology image: 20_01 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- Histology at utah.edu. Slide is proliferative phase - click forward to see secretory phase