Frontal lobe

| Frontal lobe | |

|---|---|

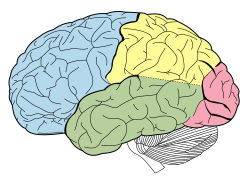

Principal fissures and lobes of the cerebrum viewed laterally (Frontal lobe is shown in blue.). | |

| |

| Details | |

| Part of | Cerebrum |

| Artery | Anterior cerebral Middle cerebral |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | lobus frontalis |

| Acronym(s) | FL |

| MeSH | D005625 |

| NeuroNames | 56 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_928 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.110 |

| TA2 | 5445 |

| FMA | 61824 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove between tissues called the central sulcus and from the temporal lobe by a deeper groove called the lateral sulcus (Sylvian fissure). The most anterior rounded part of the frontal lobe (though not well-defined) is known as the frontal pole, one of the three poles of the cerebrum.[1]

The frontal lobe is covered by the frontal cortex.[2] The frontal cortex includes the premotor cortex and the primary motor cortex – parts of the motor cortex. The front part of the frontal cortex is covered by the prefrontal cortex. The nonprimary motor cortex is a functionally defined portion of the frontal lobe.

There are four principal

The frontal lobe contains most of the dopaminergic neurons in the cerebral cortex. The dopaminergic pathways are associated with reward, attention, short-term memory tasks, planning, and motivation. Dopamine tends to limit and select sensory information coming from the thalamus to the forebrain.[4]

Structure

The frontal lobe is the largest lobe of the brain and makes up about a third of the surface area of each hemisphere.[3] On the lateral surface of each hemisphere, the central sulcus separates the frontal lobe from the parietal lobe. The lateral sulcus separates the frontal lobe from the temporal lobe.

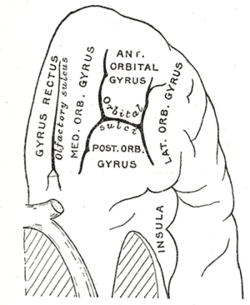

The frontal lobe can be divided into a lateral, polar, orbital (above the orbit; also called basal or ventral), and medial part. Each of these parts consists of a particular gyrus:

- Lateral part: lateral part of the superior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus

- Polar part: frontopolar cortex, transverse frontopolar gyri, frontomarginal gyrus.

- gyrus rectus

- Medial part: Medial part of the cingulate gyrus.

The gyri are separated by sulci. E.g., the precentral gyrus is in front of the central sulcus, and behind the precentral sulcus. The superior and middle frontal gyri are divided by the superior frontal sulcus. The middle and inferior frontal gyri are divided by the inferior frontal sulcus.

In humans the frontal lobe reaches full maturity only after the 20s—the prefrontal cortex, in particular, continues in maturing till the second and third decades of life[5]—which, thereafter, marks the cognitive maturity associated with adulthood. A small amount of atrophy, however, is normal in the aging person's frontal lobe. Fjell, in 2009, studied atrophy of the brain in people aged 60–91 years. The 142 healthy participants were scanned using MRI. Their results were compared to those of 122 participants with Alzheimer's disease. A follow-up one year later showed there to have been a marked volumetric decline in those with Alzheimer's and a much smaller decline (averaging 0.5%) in the healthy group.[6] These findings corroborate those of Coffey, who in 1992 indicated that the frontal lobe decreases in volume approximately 0.5–1% per year.[7]

Function

The entirety of the frontal cortex can be considered the "action cortex", much as the posterior cortex is considered the "sensory cortex". It is devoted to action of one kind or another: skeletal movement, ocular movement, speech control, and the expression of emotions. In humans, the largest part of the frontal cortex, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), is responsible for internal, purposeful mental action, commonly called reasoning or prefrontal synthesis.

The function of the PFC involves the ability to project future consequences that result from current actions. PFC functions also include override and suppression of socially unacceptable responses as well as differentiation of tasks.

The PFC also plays an important part in integrating longer non-task based memories stored across the brain. These are often memories associated with emotions derived from input from the brain's limbic system. The frontal lobe modifies those emotions, generally to fit socially acceptable norms.

Psychological tests that measure frontal lobe function include finger tapping (as the frontal lobe controls voluntary movement), the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, and measures of language, numeracy skills[8] and decision making[9] which are all controlled by frontal lobe.

Clinical significance

Damage

Damage to the frontal lobe can occur in a number of ways and result in many different consequences.

Symptoms

Common effects of damage to the frontal lobe are varied. Patients who have experienced frontal lobe trauma may know the appropriate response to a situation but display inappropriate responses to those same situations in "real life". Similarly, emotions that are felt may not be expressed in the face or voice. For example, someone who is feeling happy would not smile, and the voice would be devoid of emotion. Along the same lines, though, the person may also exhibit excessive, unwarranted displays of emotion. Depression is common in stroke patients. Also common is a loss of or decrease in motivation. Someone might not want to carry out normal daily activities and would not feel "up to it".[10] Those who are close to the person who has experienced the damage may notice changes in behavior.[11] This personality change is characteristic of damage to the frontal lobe and was exemplified in the case of Phineas Gage. The frontal lobe is the same part of the brain that is responsible for executive functions such as planning for the future, judgment, decision-making skills, attention span, and inhibition. These functions can decrease drastically in someone whose frontal lobe is damaged.[10]

Consequences that are seen less frequently are also varied. Confabulation may be the most frequently indicated "less common" effect. In the case of confabulation, someone gives false information while maintaining the belief that it is the truth. In a small number of patients, uncharacteristic cheerfulness can be noted. This effect is seen mostly in patients with lesions to the right frontal portion of the brain.[10][12]

Another infrequent effect is that of

DNA damage

In the human frontal cortex, a set of genes undergo reduced expression after age 40 and especially after age 70.

Individuals with HIV associated neurocognitive disorders accumulate nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage in the frontal cortex.[15]

Genetic

A report from the National Institute of Mental Health says a gene variant of (COMT) that reduces dopamine activity in the prefrontal cortex is related to poorer performance and inefficient functioning of that brain region during working memory, tasks, and to a slightly increased risk for schizophrenia.[16]

History

Psychosurgery

In the early 20th century, a medical treatment for

Theories of function

Theories of frontal lobe function can be separated into four categories:

- Single-process theories, which propose that "damage to a single process or system is responsible for a number of different dysexecutive symptoms"[18]

- Multi-process theories, which propose "that the frontal lobe executive system consists of a number of components that typically work together in everyday actions (heterogeneity of function)"[19]

- Construct-led theories, which propose that "most if not all frontal functions can be explained by one construct (homogeneity of function) such as working memory or inhibition"[20]

- Single-symptom theories, which propose that a specific dysexecutive symptom (e.g., confabulation) is related to the processes and construct of the underlying structures.[21]

Other theories include:

- Stuss (1999) suggests a differentiation into two categories according to homogeneity and heterogeneity of function.

- Grafman's managerial knowledge units (MKU) / structured event complex (SEC) approach (cf. Wood & Grafman, 2003)

- Miller & Cohen's integrative theory of prefrontal functioning (e.g. Miller & Cohen, 2001)

- Rolls's stimulus-reward approach and Stuss's anterior attentional functions (Burgess & Simons, 2005; Burgess, 2003; Burke, 2007).

It may be highlighted that the theories described above differ in their focus on certain processes/systems or construct-lets. Stuss (1999) remarks that the question of homogeneity (single construct) or heterogeneity (multiple processes/systems) of function "may represent a problem of semantics and/or incomplete functional analysis rather than an unresolvable dichotomy" (p. 348). However, further research will show if a unified theory of frontal lobe function that fully accounts for the diversity of functions will be available.

Other primates

Many scientists had thought that the frontal lobe was disproportionately enlarged in humans compared to other primates. This was thought to be an important feature of human evolution and seen as the primary reason why human cognition differs from that of other primates. However, this view in relation to great apes has since been challenged by

See also

References

- ^ Muzio, Bruno Di. "Frontal pole | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org.

- S2CID 149544570, retrieved 2023-06-24

- ^ ISBN 978-0683014556.

- ^ "Incoming Sensory Information - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- PMID 34645980.

- PMID 19955375.

- S2CID 20481757.

- PMID 8263463.

- PMID 28878714.

- ^ PMID 1619089.

- PMID 11222459.

- PMID 6697163.

- S2CID 74081936.

- ^ S2CID 1867993.

- S2CID 23744888.

- ^ "Gene Slows Frontal Lobes, Boosts Schizophrenia Risk". National Institute of Mental Health. May 29, 2001. Archived from the original on 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- S2CID 26307989.

- ^ (Burgess, 2003, p. 309).

- ^ (Burgess, 2003, p. 310).

- ^ (Stuss, 1999, p. 348; cf. Burgess & Simons, 2005).

- ^ (cf. Burgess & Simons, 2005).

- ^ S2CID 5921065.

- S2CID 15609709.

Further reading

- Donald T. Stuss and Robert T. Knight (Eds.), Principles of Frontal Lobe Function, Second Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 2013.

External links

- NIF Search – Frontal Lobe Archived 2013-07-03 at the Wayback Machine via the Neuroscience Information Framework