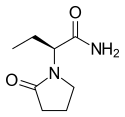

Levetiracetam

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /lɛvɪtɪˈræsɪtæm/ | ||

| Trade names | Keppra, Elepsia, Spritam, others | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| MedlinePlus | a699059 | ||

| License data | |||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

intravenous | |||

| Drug class | Racetam anticonvulsant | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | ≈100% | ||

| Protein binding | <10% | ||

| Metabolism | Enzymatic hydrolysis of acetamide group | ||

| Elimination half-life | 6–8 hrs | ||

| Excretion | Kidney | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

JSmol) | |||

SMILES

| |||

| |||

| | |||

Levetiracetam, sold under the brand name Keppra among others, is a novel antiepileptic drug

Levetiracetam was discovered in 1992 through screening in audiogenic seizure susceptible mice and, 3 years later, was reported to exhibit saturable, stereospecific binding in brain to a approximately 90 kDa protein, later identified as the ubiquitous synaptic vesicle glycoprotein SV2A."[9]

The discovery process identifying levetiracetam's antiepileptic potential was unique because it challenged several dogmas of antiepileptic drug discovery, and thereby encountered skepticism from the epilepsy community.[10]

Common side effects of levetiracetam include sleepiness, dizziness, feeling tired, and aggression.

Levetiracetam was approved for medical use in the United States in 1999

Medical uses

Focal epilepsy

Levetiracetam is effective as single-drug treatment for newly diagnosed

Partial-complex epilepsy

Levetiracetam is effective as add-on treatment for partial (focal) epilepsy.[20]

Generalized epilepsy

Levetiracetam is effective for treatment of generalized tonic-clonic epilepsy.

Levetiracetam is sometimes used off label to treat status epilepticus.[22][23]

Prevention of seizures

Based on low-quality evidence, levetiracetam is about as effective as phenytoin for prevention of early seizures after traumatic brain injury.[24] It may be effective for prevention of seizures associated with subarachnoid hemorrhages.[25]

Other

Levetiracetam has not been found to be useful for treatment of

Special groups

Levetiracetam's efficacy and tolerability in individuals with intellectual disability is comparable to those without. [31]

Studies in female pregnant rats have shown minor fetal skeletal abnormalities when given maximum recommended human doses of levetiracetam orally throughout pregnancy and lactation.[medical citation needed]

Studies were conducted to look for increased adverse effects in the elderly population as compared to younger patients. One such study published in Epilepsy Research showed no significant increase in incidence of adverse symptoms experienced by young or elderly patients with disorders of the central nervous system.[medical citation needed]

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effects of levetiracetam treatment include effects on the central nervous system such as somnolence, decreased energy, headache, dizziness, mood swings and coordination difficulties. These adverse effects are most pronounced in the first month of therapy. About 4% of patients dropped out of pre-approval clinical trials due to these side effects.[4]

About 13% of people taking levetiracetam experience adverse neuropsychiatric symptoms, which are usually mild. These include agitation, hostility, apathy, anxiety, emotional lability, and depression. Serious psychiatric adverse side effects that are reversed by drug discontinuation occur in about 1%. These include hallucinations, suicidal thoughts, or psychosis. These occur mostly within the first month of therapy, but can rarely develop at any time during treatment.[32]

Although rare, Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), which appears as a painful spreading rash with redness and blistering and/or peeling skin, have been reported in patients treated with levetiracetam.[33] The incidence of SJS following exposure to anti-epileptics such as levetiracetam is about 1 in 3,000.[34]

Levetiracetam should not be used in people who have previously shown hypersensitivity to levetiracetam or any of the inactive ingredients in the tablet or oral solution. Such hypersensitivity reactions include, but are not limited to, unexplained rash with redness or blistered skin, difficulty breathing, and tightness in the chest or airways.[4]

In a study, the incidence of decreased bone mineral density of patients on levetiracetam was significantly higher than for those on different epileptic medications.[35]

Suicide

Levetiracetam, along with other anti-epileptic drugs, can increase the risk of suicidal behavior or thoughts. Patients taking levetiracetam should be monitored closely for signs of worsening depression, suicidal thoughts or tendencies, or any altered emotional or behavioral states.[4]

Kidney and liver

Kidney impairment decreases the rate of elimination of levetiracetam from the body. Individuals with reduced kidney function may require dose adjustments, guided by monitoring of

Dose adjustment of levetiracetam is not necessary in liver impairment.[4]

Drug interactions

No significant pharmacokinetic interactions were observed between levetiracetam or its major metabolite and concomitant medications.

Mechanism of action

The exact mechanism by which levetiracetam acts to treat epilepsy is unknown. Levetiracetam does not exhibit pharmacologic actions similar to that of classical anticonvulsants. It does not inhibit voltage-dependent Na+ channels, does not affect GABAergic transmission, and does not bind to GABAergic or glutamatergic receptors.

Pharmacokinetics

The FDA provided a detailed review of the pharmacology and biopharmaceutics of Levetiracetam in 2013.[42]

Absorption

The absorption of levetiracetam tablets and oral solution is rapid and essentially complete. The bioavailability of levetiracetam is close to 100 percent, and the effect of food on absorption is minor.[4]

Distribution

The volume of distribution of levetiracetam is similar to total body water. Levetiracetam modestly binds to plasma proteins (less than 10%).[4]

Metabolism

Levetiracetam does not undergo extensive metabolism, and the metabolites formed are not active and do not exert pharmacological activity. Metabolism of levetiracetam is not by liver cytochrome P450 enzymes, but through other metabolic pathways such as hydrolysis and hydroxylation.[4]

Excretion

In persons with normal kidney function, levetiracetam is eliminated from the body primarily by the kidneys with about 66 percent of the original drug passed unchanged into urine. The plasma half-life of levetiracetam in adults is about 6 to 8 hours,[4] although the mean CSF half life of approx. 24 hours better reflects levels at site of action.[43]

Analogues

Brivaracetam, a chemical analogue to levetiracetam, is a racetam derivative with similar properties.

Society and culture

Levetiracetam is available as regular and extended release oral formulations and as intravenous formulations.[44]

The immediate release tablet has been available as a generic in the United States since 2008, and in the UK since 2011.[45][19] The patent for the extended release tablet will expire in 2028.[46]

The branded version Keppra is manufactured by UCB Pharmaceuticals S.A.[3][4][5][6]

In 2015, Aprecia's

Legal status

Australia

Levetiracetam is a Schedule 4 substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (February 2020).[49] A Schedule 4 substance is classified as "Prescription Only Medicine, or Prescription Animal Remedy – Substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription."[49]

Japan

Under Japanese law, levetiracetam and other racetams cannot be brought into the country except for personal use by a traveler for whom it has been prescribed.[50] Travelers who plan to bring more than a month's worth must apply for an import certificate, known as a Yakkan Shoumei (薬監証明, yakkan shōmei).[51]

Research

Levetiracetam has been studied in the past for treating symptoms of neurobiological conditions such as Tourette syndrome,[52] and anxiety disorder.[53] However, its most serious adverse effects are behavioral, and its benefit-risk ratio in these conditions is not well understood.[53]

Levetiracetam is being tested as a drug to reduce hyperactivity in the hippocampus in Alzheimer's disease.[54]

Additionally, Levetiracetam has been experimentally shown to reduce Levodopa-induced dyskinesia,[55] a type of movement disorder, or dyskinesia associated with the use of Levodopa, a medication used to treat Parkinson's disease.

Of the ten medications evaluated in a 2023 systematic review of the literature, levetiracetam was found to be the only medication with sufficient evidence showing that it may cause seizure freedom in some infants.[56] Further, adverse effects from levetiracetam were rarely severe enough for the medication to be discontinued in this age group. Because available research included only 2 published studies reporting seizure freedom rates, however, the strength of the evidence was judged to be low.[56]

References

- ^ "Levetiracetam Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Keppra 100 mg/ml concentrate for solution for infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Keppra- levetiracetam tablet, film coated Keppra- levetiracetam solution". DailyMed. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Keppra XR- levetiracetam tablet, film coated, extended release". DailyMed. 4 November 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Keppra- levetiracetam injection, solution, concentrate". DailyMed. 4 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ ).

- ^ a b c d e "Levetiracetam Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^

Rogawski M (August 2008). "Brivaracetam: a rational drug discovery success story". Br J Pharmacol. 154 (8): 1555–1557. PMID 18552880.

- ^

Klitgaard H, et al. (November 2007). "Levetiracetam: the first SV2A ligand for the treatment of epilepsy". Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2 (11): 1537–1545. PMID 23484603.

- ISBN 9780198791577.

- ^ PMID 37897555.

- ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Levetiracetam Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- S2CID 52174058.

- ^ PMID 35363878.

- ^ PMID 22972056.

- PMID 29784458.

- ^ BNF 59. BMA & RPSGB. 2010.

- S2CID 4675838.

- S2CID 1032139.

- PMID 27749510.

- S2CID 7555384.

- from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- PMID 22013182.

- PMID 24472258.

- S2CID 36509998.

- PMID 24350200.

- PMID 38897161.

- PMID 18728811.

- PMID 23036769.

- S2CID 10305861.

- PMID 22541979.

- S2CID 35576679.

- S2CID 13555324.

- PMID 24550884.

- PMID 15210974.

- S2CID 8333373.

- PMID 16621450.

- ^ Dimova H, et al. (3 October 2013), Clinical Pharmacology/Biopharmaceutics Review, US Food & Drug Administration (FDA).

- PMID 31523280.

- ^ "Levetiracetam Injection Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Branch Website Management. "Patent Terms Extended Under 35 USC §156". www.uspto.gov. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Webber K (12 September 2011). "FDA Access Data" (PDF). ANDA 091291. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "FDA approves the first 3D-printed drug product". KurzweilAI. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- S2CID 244421616.

- ^ a b Poisons Standard February 2020 Archived 2 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. comlaw.gov.au

- ^ "Information for those who are bringing medicines for personal use into Japan". Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Q&A for those who are importing medicines into Japan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- PMID 20628631.

- ^ PMID 19265183.

- PMID 28560709.

- PMID 25692070.

- ^ from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.