Phenobarbital

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Luminal, Sezaby |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682007 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

parenteral | |

| Drug class | Barbiturate |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Protein binding | 20 to 45% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP2C19) |

| Onset of action | within 5 min (IV) and 30 min (PO)[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 53 to 118 hours |

| Duration of action | 4 hrs[4] to 2 days[5] |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone or phenobarb, sold under the brand name Luminal among others, is a

Side effects include a

Phenobarbital was discovered in 1912 and is the oldest still commonly used

Medical uses

Phenobarbital is used in the treatment of all types of seizures, except

The first-line drugs for treatment of

Phenobarbital is the first-line choice for the treatment of neonatal seizures.[22][23][24][25] Concerns that neonatal seizures in themselves could be harmful make most physicians treat them aggressively. No reliable evidence, though, supports this approach.[26]

Phenobarbital is sometimes used for alcohol detoxification and benzodiazepine detoxification for its sedative and anti-convulsant properties. The benzodiazepines chlordiazepoxide (Librium) and oxazepam (Serax) have largely replaced phenobarbital for detoxification.[27]

Phenobarbital is useful for insomnia and anxiety.[28]

Other uses

Phenobarbital properties can effectively reduce tremors and seizures associated with abrupt withdrawal from benzodiazepines.

Phenobarbital is a cytochrome P450 inducer and is used to reduce the toxicity of some drugs.[citation needed]

Phenobarbital is occasionally prescribed in low doses to aid in the conjugation of

Phenobarbital can also be used to relieve cyclic vomiting syndrome symptoms.Phenobarbital is a commonly used agent in high purity and dosage for lethal injection.[citation needed]

In infants suspected of neonatal

Phenobarbital is used as a secondary agent to treat newborns with

In massive doses, phenobarbital is prescribed to terminally ill people to allow them to end their life through

Like other barbiturates, phenobarbital

The synthesis of a photoswitchable analog (DASA-barbital) and phenobarbital has been described for use as research compound in photopharmacology.[34]

Side effects

Sedation and hypnosis are the principal side effects (occasionally, they are also the intended effects) of phenobarbital.

Phenobarbital is a cytochrome P450 hepatic enzyme inducer. It binds transcription factor receptors that activate cytochrome P450 transcription, thereby increasing its amount and thus its activity.[36] Caution is to be used with children. Among anti-convulsant drugs, behavioural disturbances occur most frequently with clonazepam and phenobarbital.[37]

Contraindications

Overdose

Phenobarbital causes a depression of the body's systems, mainly the

The

Treatment of phenobarbital overdose is

Mechanism of action

Phenobarbital is as an

Pharmacokinetics

Phenobarbital has an oral

Veterinary uses

Phenobarbital is one of the first line drugs of choice to treat epilepsy in dogs, as well as cats.[9]

It is also used to treat feline hyperesthesia syndrome in cats when anti-obsessional therapies prove ineffective.[43]

It may also be used to treat seizures in horses when benzodiazepine treatment has failed or is contraindicated.[44]

History

The first barbiturate drug, barbital, was synthesized in 1902 by German chemists Emil Fischer and Joseph von Mering and was first marketed as Veronal by Friedr. Bayer et comp. By 1904, several related drugs, including phenobarbital, had been synthesized by Fischer. Phenobarbital was brought to market in 1912 by the drug company Bayer as the brand Luminal. It remained a commonly prescribed sedative and hypnotic until the introduction of benzodiazepines in the 1960s.[45]

Phenobarbital's soporific, sedative and hypnotic properties were well known in 1912, but it was not yet known to be an effective anti-convulsant. The young doctor

In 1939, a German family asked Adolf Hitler to have their disabled son killed; the five-month-old boy was given a lethal dose of Luminal after Hitler sent his own doctor to examine him. A few days later 15 psychiatrists were summoned to Hitler's Chancellery and directed to commence a clandestine program of involuntary euthanasia.[48][49]

In 1940, at a clinic in Ansbach, Germany, around 50 intellectually disabled children were injected with Luminal and killed that way. A plaque was erected in their memory in 1988 in the local hospital at Feuchtwanger Strasse 38, although a newer plaque does not mention that patients were killed using barbiturates on site.[50][51] Luminal was used in the Nazi children's euthanasia program until at least 1943.[52][53]

Phenobarbital was used to treat

Phenobarbital was used for over 25 years as

Society and culture

Names

Phenobarbital is the

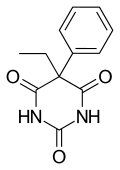

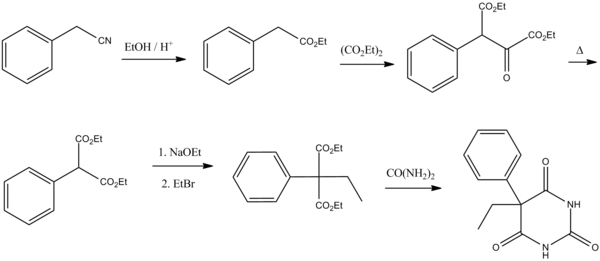

Synthesis

The first of these methods consists of a

The second approach utilizes diethyl carbonate in the presence of a strong base to give α-phenylcyanoacetic ester.[62][63] Alkylation of this ester using ethyl bromide proceeds via a nitrile anion intermediate to give the α-phenyl-α-ethylcyanoacetic ester.[64] This product is then further converted into the 4-iminoderivative upon condensation with urea. Finally acidic hydrolysis of the resulting product gives phenobarbital.[65]

A new synthetic route based on diethyl 2-ethyl-2-phenylmalonate and urea has been described.[34]

Regulation

The level of regulation includes

Selected overdoses

A mysterious woman, known as the Isdal Woman, was found dead in Bergen, Norway, on 29 November 1970. Her death was caused by some combination of burns, phenobarbital, and carbon monoxide poisoning; many theories about her death have been posited, and it is believed that she may have been a spy.[68]

British veterinarian Donald Sinclair, better known as the character Siegfried Farnon in the "All Creatures Great and Small" book series by James Herriot, committed suicide at the age of 84 by injecting himself with an overdose of phenobarbital. Activist Abbie Hoffman also committed suicide by consuming phenobarbital, combined with alcohol, on April 12, 1989; the residue of around 150 pills was found in his body at autopsy.[69]

Thirty-nine members of the Heaven's Gate UFO cult committed mass suicide in March 1997 by drinking a lethal dose of phenobarbital and vodka "and then lay down to die" hoping to enter an alien spacecraft.[70]

References

- ISBN 9780323496407.

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Sezaby- phenobarbital sodium injection". DailyMed. 6 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Phenobarbital". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved Aug 14, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ PMID 23284189.

- S2CID 25553143.

- PMID 25340221– via PubMed.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8138-1249-6.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Phenobarbital use while Breastfeeding". 2013. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-0278-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-04.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-5777-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-05.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- NICE (2005-10-27). "CG20 Epilepsy in adults and children: NICE guideline". NHS. Archived from the originalon 2006-10-09. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ a b British National Formulary 51

- PMID 23440786.

- PMID 30353945.

- ISBN 978-0-85369-676-6.

- S2CID 11274515.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-1667-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-21.

- S2CID 237010210.

- ISBN 978-0-85369-676-6.

- ISBN 978-1-888799-30-9.

- ^ Sheth RD (2005-03-30). "Neonatal Seizures". eMedicine. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2006-07-09. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- S2CID 29887880.

- from the original on 2010-12-28. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ISBN 9780781765879.

- ISBN 978-0071802154.

Bilirubin concentrations during phenobarbital administration do not return to normal but are typically in the range of 51-86 µmol/L (3-5 mg/dL). Although the incidence of kernicterus in CN-II is low, instances have occurred, not only in infants but also in adolescents and adults, often in the setting of an intercurrent illness, fasting, or another factor that temporarily raises the serum bilirubin concentration above baseline and reduces serum albumin levels. For this reason, phenobarbital therapy is highly recommended, a single bedtime dose often sufficing to maintain clinically safe serum bilirubin concentrations.

- ^ Tamayo V, Del Valle Díaz S, Durañones Góngora S, Corina Domínguez Cardosa M, del Carmen Clares Pochet P (December 2012). "Pruebas de laboratorio en el síndrome de Gilbert consecutivo a hepatitis" [Laboratory tests in Gilbert's syndrome after hepatitis] (PDF). Medisan (in Spanish). 16 (12): 1823–1830.

- ^ "Washington State Department of Health 2015 Death with Dignity Act Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- PMID 18568113.

Despite their widespread use during the first half of the 20th century, no barbiturate succeeded in eliminating the main drawbacks of these drugs, which were the phenomena of dependence and death by overdose

- ^ Barbiturate abuse in the United States, 1973

- ^ S2CID 251623598.

- ^ a b "Phenobarbital dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". reference.medscape.com. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- S2CID 37595905.

- S2CID 20440040.

- ^ a b Habal R (2006-01-27). "Barbiturate Toxicity". eMedicine. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ^ "Barbiturate intoxication and overdose". MedLine Plus. Archived from the original on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- PMID 30335310. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- PMID 25307572.

- ISBN 9780323393072.

- ^ Dodman N. "Feline Hyperesthesia (FHS)". PetPlace.com. Archived from the original on 2011-11-23. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ISBN 978-0-911910-50-6.

- ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ Enersen OD. "Alfred Hauptmann". Archived from the original on 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ISBN 978-1-85070-391-4.

- ^ Zoech I (12 October 2003). "Named: the baby boy who was Nazis' first euthanasia victim". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

The case was to provide the rationale for a secret Nazi decree that led to 'mercy killings' of almost 300,000 mentally and physically handicapped people. The Kretschmars wanted their son dead but most of the other children were forcibly taken from their parents to be killed.

- ^ Smith WJ (26 March 2006). "Killing Babies, Compassionately". Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Hitler later signed a secret decree permitting the euthanasia of disabled infants. Sympathetic physicians and nurses from around the country--many not even Nazi party members--cooperated in the horror that followed. Formal 'protective guidelines' were created, including the creation of a panel of 'expert referees,' which judged which infants were eligible for the program.

- ^ Kaelber L (8 March 2013). "Kinderfachabteilung Ansbach". Sites of Nazi "Children's 'Euthanasia'" Crimes and Their Commemoration in Europe. University of Vermont. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

In the late 1980s, important developments occurred at the clinic that led to the first publication on the subject and the display of two plaques. Dr Reiner Weisenseel wrote his dissertation under Dr Athen, then the director of the Ansbacher Bezirkskrankenhaus, on the involvement of the clinic in Euthanasia crimes, including the operation of the Kinderfachabteilung. In 1988 two members of the Green Party as well as the regional diet (Bezirkstag) were horrified to find portraits of physicians involved in Nazi euthanasia crimes among the honorary display of medical personnel in the administrative building, and they successfully petitioned to have these portraits removed. Since 1992 a plaque hangs in the entry hall way of the administrative building. It reads: 'In the Third Reich the Ansbach facility delivered to their death more than 2000 of the patients entrusted to it as life unworthy of living: They were transferred to killing facilities or starved to death. In their own way many people incurred responsibility.' It continues: 'Half a century later full of shame we commemorate the victims and call to remember the Fifth Commandment.' The killing of children specifically transferred to the clinic to be murdered is not noted. The plaque does not address that that euthanasia victims were not only starved or transported to gassing facilities but killed using barbiturates on site.

- ^ Binder J (October 2011). "Die Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Ansbach während des Nationalsozialismus" (PDF). Bezirksklinikum Ansbach (in German). Bezirkskliniken Mittelfranken. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Kaelber L (Spring 2013). "Jewish Children with Disabilities and Nazi "Euthanasia" Crimes" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Carolyn and Leonard Miller Center for Holocaust Studies. University of Vermont. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Two Polish physicians reported at the time that 235 children from ages up to 14 were listed in the booklet, of whom 221 had died. An investigation revealed that the medical records of the children had been falsified, as those records showed a far lower dosage of Luminal given to them than was entered into the Luminal booklet. For example, the medical records for Marianna N. showed for 16 January 1943 (she died on that day) a dosage of 0.1 g of Luminal, whereas the Luminal booklet showed the actual dosage as 0.4 g, or four times the dosage recommended for her body weight.

- S2CID 39858807.

- ^ Pepling RS (June 2005). "Phenobarbital". Chemical and Engineering News. 83 (25). Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ISBN 978-1-888799-30-9.

- ^ Baumann R (2005-02-14). "Febrile Seizures". eMedicine. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2006-09-06. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ various (March 2005). "Diagnosis and management of epilepsies in children and young people" (PDF). Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-06-10. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-582-46236-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-11.

- ISBN 978-0-471-00726-5. Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- ^ US 2358072, Inman MT, Bilter WP, "Preparation of Phenobarbital", issued 12 September 1944, assigned to Kay Fries Chemicals, Inc..

- ^ "DEA Diversion Control Division" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-17. Retrieved 2016-04-13. pp 12 printed PDF 23.I.2016

- ^ "DEA Diversion Control Division" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-17. Retrieved 2016-04-13. page 1,7, 12, accessed 23.I.2016

- ^ Cheung H (13 May 2017). "The mystery death haunting Norway for 46 years". BBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ King W (April 19, 1989). "Abbie Hoffman Committed Suicide Using Barbiturates, Autopsy Shows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ "Heaven's Gate cult members found dead". History Channel. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

External links

- "Phenobarbital". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.