Lod

Lod

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 31°57′7″N 34°53′17″E / 31.95194°N 34.88806°E | |

| Country | |

| District | Central |

| Subdistrict | Ramla Subdistrict |

| Founded | 5600–5250 BCE (Initial settlement) 1465 BCE (Canaanite/Israelite town) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Yair Revivo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12,226 dunams (12.226 km2 or 4.720 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

| • Total | 85,351 |

| • Density | 7,000/km2 (18,000/sq mi) |

Lod (

Lod is an ancient city, and

Following the Arab conquest of the Levant, Lod served as the capital of Jund Filastin; however, a few decades later, the seat of power was transferred to Ramla, and Lod slipped in importance.[3][8] Under Crusader rule, the city was a Catholic diocese of the Latin Church and it remains a titular see to this day.[citation needed]

Lod underwent a major change in its population in the mid-20th century.

Today, Lod is one of Israel's mixed cities, with an Arab population of 30%.[14] Lod is one of Israel's major transportation hubs. The main international airport, Ben Gurion Airport, is located 8 km (5 miles) north of the city. The city is also a major railway and road junction.[3]

Religious references

The Hebrew name Lod appears in the Hebrew Bible as a town of Benjamin, founded along with Ono by Shamed or Shamer (1 Chronicles 8:12; Ezra 2:33; Nehemiah 7:37; 11:35). In Ezra 2:33, it is mentioned as one of the cities whose inhabitants returned after the Babylonian captivity. Lod is not mentioned among the towns allocated to the tribe of Benjamin in Joshua 18:11–28.[15]

The name Lod derives from a tri-consonental not extant in Northwest Semitic, but only in Arabic (“to quarrel; withhold, hinder”). An Arabic etymology of such an ancient name is unlikely (the earliest attestation is from the Achaemenid period).[16]

In the New Testament, the town appears in its Greek form, Lydda,[17][18][19] as the site of Peter's healing of Aeneas in Acts 9:32–38.[20]

The city also finds reference in an Islamic

In those sources, (al-)Ludd [51, 54] (Pr: SWP, M, O: mostly Lidd, il-Lidd) < OT Ld, Greek Λύδδα (-α is a purely Greek insertion) reflects a qull-formation of L-D-D.It is aptly rejected by al-Hilou who also states that the root with the same meaning is extant in Ancient 10 Marom 2022b, 109–113. 11 Nos. 1, 2; compare toponyms recorded in the 1596/7 mufaṣṣal defters by Hütteroth/Abdulfattah 1977.

<This is the Authors’ Version of the Paper. The official, paginated, Version of Record (VOR) was published as: Marom, R. and Zadok, R., “Early-Ottoman Palestinian Toponymy: A Linguistic Analysis of the (Micro-)toponyms in Haseki Sultan’s Endowment Deed (1552),” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 139.2 (2023), pp. 258-289> 9South Arabian12. However, such a root is not listed in Beeston et al. 1982. The Arabic derivation offered by Yaqūt from the causative stem with the meaning “strongly broken” is morphologically unlikely13. Thanks to the continuous occupation and scriptural references the Philippi's law, e.g. a vowel shift in Biblical Hebrew from *i to *a in closed, stressed syllables, did not apply here14

History

Antiquity

The first occupation was in the Neolithic period.[22][23]Occupation continued in the Chalcolithic.[24][25][26]Pottery finds have dated the initial settlement in the area now occupied by the town to 5600–5250 BCE.[27]

Early Bronze

In the Early Bronze, it was an important settlement in the central coastal plain between the Judean Shephelah and the Mediterranean coast, along Nahal Ayalon.[28] Other important nearby sites were Tel Dalit, Tel Bareqet, Khirbat Abu Hamid (Shoham North), Tel Afeq, Azor and Tel Aviv.

Two architectural phases belong to the late EB I in Area B.[29] The first phase had a mudbrick wall, while the late phase included a circulat stone structure. Later excavations have produced an occupation later, Stratum IV.[30] It consists of two phases, Stratum IVb with mudbrick wall on stone foundations and rounded exterior corners. In Stratum IVa there was a mudbrick wall with no stone foundations, with imported Egyptian potter and local pottery imitations.

Another excavations revealed nine occupation strata. Strata VI-III belonged to Early Bronze IB. The material culture showed Egyptian imports in strata V and IV.[31]

Occupation continued into Early Bronze II with four strata (V-II). There was continuity in the material culture and indications of centralized urban planning.

Middle Bronze

North to the tell were scattered MB II burials.[32]

Late Bronze

The earliest written record is in a list of Canaanite towns drawn up by the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III at Karnak in 1465 BCE.[33]

Classical era

From the fifth century BCE until the

According to British historian

Roman era

The Jewish community in Lod during the Mishnah and Talmud era is described in a significant number of sources, including information on its institutions, demographics, and way of life. The city reached its height as a Jewish center between the First Jewish-Roman War and the Bar Kokhba revolt, and again in the days of Judah ha-Nasi and the start of the Amoraim period. The city was then the site of numerous public institutions, including schools, study houses, and synagogues.[4]

In 43 BC, Cassius, the Roman governor of Syria, sold the inhabitants of Lod into slavery, but they were set free two years later by Mark Antony.[37][38]

During the First Jewish–Roman War, the Roman

In the period following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Rabbi Tarfon, who appears in many Tannaitic and Jewish legal discussions, served as a rabbinic authority in Lod.[40]

During the

In 200 CE, emperor

Byzantine period

In December 415, the

The

Early Muslim period

After the

The city was visited by the local Arab geographer

Crusader and Ayyubid period

The Crusaders occupied the city in 1099 and named it St Jorge de Lidde.[35] It was briefly conquered by Saladin, but retaken by the Crusaders in 1191. For the English Crusaders, it was a place of great significance as the birthplace of Saint George. The Crusaders made it the seat of a Latin Church diocese,[53] and it remains a titular see.[37] It owed the service of 10 knights and 20 sergeants, and it had its own burgess court during this era.[54]

In 1226, Ayyubid Syrian geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi visited al-Ludd and stated it was part of the Jerusalem District during Ayyubid rule.[55]

Mamluk period

Sultan

Ottoman period

In 1517, Lydda was incorporated into the

By 1596 Lydda was a part of the

In 1051 AH/1641/2, the Bedouin tribe of al-Sawālima from around Jaffa attacked the villages of Subṭāra, Bayt Dajan, al-Sāfiriya, Jindās, Lydda and Yāzūr belonging to Waqf Haseki Sultan.[62]

The village appeared as Lydda, though misplaced, on the map of Pierre Jacotin compiled in 1799.[63]

Missionary

In 1869, the population of Ludd was given as: 55 Catholics, 1,940 "Greeks", 5 Protestants and 4,850 Muslims.

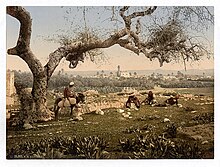

In 1882, the

British Mandate

From 1918, Lydda was under the administration of the

At the time of the 1922 census of Palestine, Lydda had a population of 8,103 inhabitants (7,166 Muslims, 926 Christians, and 11 Jews),[68] the Christians were 921 Orthodox, 4 Roman Catholics and 1 Melkite.[69] This had increased by the 1931 census to 11,250 (10,002 Muslims, 1,210 Christians, 28 Jews, and 10 Bahai), in a total of 2475 residential houses.[70]

In 1938, Lydda had a population of 12,750.[71]

In 1945, Lydda had a population of 16,780 (14,910 Muslims, 1,840 Christians, 20 Jews and 10 "other").

State of Israel

The

In 1948, the population rose to 50,000 as Arab refugees fleeing other areas made their way there.[66] All but 700[80] to 1,056[12] were expelled by order of the Israeli high command, and forced to walk 17 km (10+1⁄2 mi) to the Jordanian Arab Legion lines. Estimates of those who died from exhaustion and dehydration vary from a handful to 355.[81][82] The town was subsequently sacked by the Israeli army.[83] Some scholars, including Ilan Pappé, characterize this as ethnic cleansing.[84] The few hundred Arabs who remained in the city were soon outnumbered by the influx of Jewish refugees who immigrated to Lod from August 1948 onward, most of them from Arab countries.[12] As a result, Lod became a predominantly Jewish town.[74][85]

After the establishment of the state, the biblical name Lod was readopted.[86]

-

Lydda five months after Operation Danny. December 1948.

-

Lydda, 1948

-

Church of Saint George and Mosque of Al-Khadr, after the battle. 1948

-

Palmach 3 inch mortar in front of Lydda mosque. 1948

The Jewish immigrants who settled Lod came in waves,

Since 2008, many urban development projects have been undertaken to improve the image of the city. Upscale neighbourhoods have been built, among them Ganei Ya'ar and Ahisemah, expanding the city to the east. According to a 2010 report in the Economist, a three-meter-high wall was built between Jewish and Arab neighbourhoods and construction in Jewish areas was given priority over construction in Arab neighborhoods. The newspaper says that violent crime in the Arab sector revolves mainly around family feuds over turf and honour crimes.[88] In 2010, the Lod Community Foundation organised an event for representatives of bicultural youth movements, volunteer aid organisations, educational start-ups, businessmen, sports organizations, and conservationists working on programmes to better the city.[89]

In the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis, a state of emergency was declared in Lod after Arab rioting led to the death of an Israeli Jew.[90] The Mayor of Lod, Yair Revivio, urged Prime Minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu to deploy Israel Border Police to restore order in the city.[91][92] This was the first time since 1966 that Israel had declared this kind of emergency lockdown.[93][94] International media noted that both Jewish and Palestinian mobs were active in Lod, but the "crackdown came for one side" only.[95][96][97][98][99]

Demographics

In the 19th century, Lod was an exclusively Muslim-Christian town, with an estimated 6,850 inhabitants, of whom approximately 2,000 (29%) were Christian.[100]

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the population of Lod in 2010 was 69,500 people.[101]

According to the 2019 census, the population of Lod was 77,223, of which 53,581 people, comprising 69.4% of the city's population, were classified as "Jews and Others", and 23,642 people, comprising 30.6% as "Arab".[1]

Education

According to CBS, 38 schools and 13,188 pupils are in the city. They are spread out as 26 elementary schools and 8,325 elementary school pupils, and 13 high schools and 4,863 high school pupils. About 52.5% of 12th-grade pupils were entitled to a matriculation certificate in 2001.[citation needed]

Economy

The airport and related industries are a major source of employment for the residents of Lod. A

Art and culture

In 2009-2010,

Archaeology

A well-preserved mosaic floor dating to the Roman period was excavated in 1996 as part of a salvage dig conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Municipality of Lod, prior to widening HeHalutz Street. According to

Jacob Fisch, executive director of the Friends of the Israel Antiquities Authority, a worker at the construction site noticed the tail of a tiger and halted work.

The Lod Community Archaeology Program, which operates in ten Lod schools, five Jewish and five Israeli Arab, combines archaeological studies with participation in digs in Lod.[106]

Sports

The city's major football club, Hapoel Bnei Lod, plays in Liga Leumit (the second division). Its home is at the Lod Municipal Stadium. The club was formed by a merger of Bnei Lod and Rakevet Lod in the 1980s. Two other clubs in the city play in the regional leagues: Hapoel MS Ortodoxim Lod in Liga Bet and Maccabi Lod in Liga Gimel.

Hapoel Lod played in the top division during the 1960s and 1980s, and won the State Cup in 1984. The club folded in 2002. A new club, Hapoel Maxim Lod (named after former mayor Maxim Levy) was established soon after, but folded in 2007.

Notable people

- Rabbi Akiva, Talmudic sage

- Etti Ankri (born 1963), singer

- Oshri Cohen (born 1984), actor

- St George, Patron Saint of Beirut, Palestine, England, Russia, and Catalonia

- George Habash (1926–2008), founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

- Eliezer ben Hurcanus, Talmudic sage

- Joshua ben Levi, Talmudic sage

- Tamer Nafar (born 1979), rapper

- Suhell Nafar, rapper

- Rabbi Tarfon, Talmudic sage

- Salim Tuama (born 1979), footballer

- Sami Abu Shehadeh (born 1975), politician

Twin towns-sister cities

Lod is

See also

- Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

- Operation Danny

References

- ^ a b c "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Commenge, Catherine. "Lod Newe Yarak: a roman pottery kiln and Pottery Neolithic A remains".

- ^ a b c d e "Lod | City, Israel, Palestine, & History | Britannica". britannica.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ )

- S2CID 218824016, retrieved 27 June 2022,

By 1099 crusading armies had captured the city of Lydda, the site of St George's martyrdom and tomb.

- JSTOR 44169945.

- ISSN 0766-5598.

- ^ a b Le Strange, 1890, p. 308

- ^ S2CID 162633906.

The Palestinian quarters of Safad, Tiberias, Haifa, Jaffa, and West Jerusalem and the Jewish quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem were in a state of sociological catastrophe, with no community to speak of to even bury the dead and mourn the old existence... By late 1949 only one of the five towns that had been effectively mixed on the eve of the war, namely, Haifa, still had a Palestinian contingent. Even there, however, the urban mix had been transformed beyond recognition. The 3,000 remaining Palestinians, now representing less than 5 percent of the original community, had been uprooted and forced to relocate to downtown Wadi Ninas... More relevant for our concerns here are Acre, Lydda, Ramle, and Jaffa, which, although exclusively Palestinian before the war of 1948, became predominantly Jewish mixed towns after. All of them had their residual Palestinian populations concentrated in bounded compounds, in one case (Jaffa) surrounded for a while by barbed wire. As late as the summer of 1949, all of these compounds were subjected to martial law.

- ^ Shapira, Anita, “Politics and Collective Memory: the Debate Over the 'New Historians' in Israel,” History and Memory 7 (1) (Spring 1995), pp. 9ff, 12–13, 16–17.

- ^ Blumenthal, 2013, p. 420

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-07164-3

- ^ Morris, 2004, pp. 414-461.

- ^ Uploads (p. 18), Jerusaleminstitute.org. Accessed 1 November 2022.

- ^ Exell, J. S. and Spencer-Jones, H. (eds), Pulpit Commentary on 1 Chronicles 8, biblehub.com. Accessed 8 February 2020.

- ^ Marom, Roy (2023). "Early-Ottoman Palestinian Toponymy: A Linguistic Analysis of the (Micro-)Toponyms in Haseki Sultan's Endowment Deed (1552)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 139 (2).

- ^ Bible Dictionary, "Lydda"

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, "Lod; Lydda"

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 216

- ^ "Lod," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009. "And it came to pass, as Peter passed throughout all quarters, he came down also to the saints which dwelt at Lydda", Acts 9:32–38

- ^ "Signs of the Appearance of the Dajjal". Missionislam.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Yannai and Marder 2000

- ^ Brink 1999, 2002, Brink et al. 2015

- ^ Brink 1999, 2002, Brink et al. 2015

- ^ Paz, Rosenberg and Nativ 2005:131–154

- ^ Yannai and Marder 2000

- ^ Schwartz, Joshua J. Lod (Lydda), Israel: from its origins through the Byzantine period, 5600 B.C.-640 A.D.. Tempus Reparatum, 1991, p. 39.

- ^ Amir Golani (2022) Early Bronze Age Remains at Tel Lod, 'Atiqot 108

- ^ Keplan 1977

- ^ Brink 1999, 2002; Brink et al. 2015

- ^ Paz, Rosenberg and Nativ 2005:131–154

- ^ Segal 2012

- ^ a b "Excursions in Terra Santa". Franciscan Cyberspot. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ Rozenfeld, 2010, p. 52

- ^ a b "Lod," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin. Dearest Auntie Flori: The Story of the Jewish People. New York: Harper Collins 2002, p. 82; also see Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 14: 208

- ^ a b c d Lydda, Catholic-hierarchy.org. Accessed 1 November 2022.

- ^ Josephus, "Jewish War", I, xi, 2; "Antiquities", XIV xii, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Michael Avi-Yonah, s.v. "Lydda," Encyclopaedia Judaica. Accessed 1 November 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-134-62559-8– via Google Books.

- ^ Holder, 1986, p. 52

- ^ Ta'anit ii. 10; Yer. Ta'anit ii. 66a; Yer. Meg. i. 70d; R. H. 18b

- ^ Pes. 50a; B. B. 10b; Eccl. R. ix. 10

- ^ Cecil Roth, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1972, p. 619.

- ^ Smallwood, 2001, p. 241

- ISBN 978-965-208-107-0

- ^ Frenkel, Sheera and Low, Valentine. "Why Lod, the other land of St George, isn't for the faint-hearted", The Times, 23 April 2009.

- ^ The Madaba Mosaic Map, Jerusalem 1954, pp. 61–62

- ISBN 978-90-390-0011-3. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 28

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 303

- ^ Le Strange, 1890 p. 493

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Pringle, 1998, p. 11

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 494

- ^ a b c d e Petersen, 2001, p. 203

- ^ Moudjir ed-dyn, 1876, Sauvaire (translation), pp. 210-213

- ^ al-Ẓāhirī, 1894, pp. 118-119

- ^ Singer, 2002, p. 49

- ^ Petersen, 2005, p. 131

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 154

- ^ Marom, Roy (2022-11-01). "Jindās: A History of Lydda's Rural Hinterland in the 15th to the 20th Centuries CE". Lod, Lydda, Diospolis: 13-14.

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 171 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomson, 1859, pp. 292-3

- ^ a b Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 252

- ^ a b c d Shahin, 2005, p. 260

- ^ "Ben Gurion Airport". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, p. 21

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 46

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 21

- ^ Village Statistics (PDF). 1938. p. 59.

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 30

- ^ "Lod," 2 January 1949, IS archive Gimel/5/297 in Yacobi, 2009, p. 31.

- ^ a b Monterescu and Rabinowitz, 2012, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Sa'di and Abu-Lughod, 2007, pp. 91-92.

- ^ For one account, interspersed with interviews with IDF soldiers, see Ari Shavit, My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2013, pp. 99–132.

- ^ Tal, 2004, p. 311.

- ^ Sefer Hapalmah ii (The Book of the Palmah), p. 565; and KMA-PA (Kibbutz Meuhad Archives – Palmah Archive). Quoted in Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 205 Morris writes: "[...] dozens of unarmed detainees in the mosque and church in the centre of the town were shot and killed."

- Bechor Sheetrit, the Israeli Minister for Minority Affairs at the time, cited in Yacobi, 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Spiro Munayyer, The Fall of Lydda( اللد لن تقع), Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer, 1998), pp. 80–98. See also Yitzhak Rabin's diaries, quoted here [1].

- ^ Holmes et al., 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Morris, Benny "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948", Middle East Journal 40 (1986), p. 88.

- ^ For the use of the term "ethnic cleansing", see, for example, Pappé 2006.

- On whether what occurred in Lydda and Ramle constituted ethnic cleansing:

- Morris 2008, p. 408: "although an atmosphere of what would later be called ethnic cleansing prevailed during critical months, transfer never became a general or declared Zionist policy. Thus, by war's end, even though much of the country had been 'cleansed' of Arabs, other parts of the country—notably central Galilee — were left with substantial Muslim Arab populations, and towns in the heart of the Jewish coastal strip, Haifa and Jaffa, were left with an Arab minority."

- Spangler 2015, p. 156: "During the Nakba, the 1947 [sic] displacement of Palestinians, Rabin had been second in command over Operation Dani, the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian towns of towns of Lydda and Ramle."

- Schwartzwald 2012, p. 63: "The facts do not bear out this contention [of ethnic cleansing]. To be sure, some refugees were forced to flee: fifty thousand were expelled from the strategically located towns of Lydda and Ramle ... But these were the exceptions, not the rule, and ethnic cleansing had nothing to do with it."

- Golani and Manna 2011, p. 107: "The expulsion of some 50,000 Palestinians from their homes ... was one of the most visible atrocities stemming from Israel's policy of ethnic cleansing."

- ^ Yacobi, 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Yacobi, 2009, p. 29: "The occupation of Lydda by Israel in the 1948 war did not allow the realization of Pocheck's garden city vision. Different geopolitics and ideologies began to shape Lydda's urban landscape ... [and] its name was changed from Lydda to Lod, which was the region's biblical name"; also see Pearlman, Moshe and Yannai, Yacov. Historical sites in Israel. Vanguard Press, 1964, p. 160. For the Hebrew name being used by inhabitants before 1948, see A Cyclopædia of Biblical literature: Volume 2, by John Kitto, William Lindsay Alexander. p. 842 ("... the old Hebrew name, Lod, which had probably been always used by the inhabitants, appears again in history."); And Lod (Lydda), Israel: from its origins through the Byzantine period, 5600 B.C.E.-640 C.E., by Joshua J. Schwartz, 1991, p. 15 ("the pronunciation Lud began to appear along with the form Lod")

- ^ "Polishing a Lost Gem to Dazzle Tourists", New York Times. 8 July 2009.

- ^ Pulled Apart. The Economist, 14 October 2010.

- ^ Ron Friedman, Pushing for a better tomorrow in 8,000-year-old Lod, The Jerusalem Post, 8 April 2010. Accessed 25 March 2020.

- ^ "IDF enters Lod as city goes into emergency lockdown". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "Amid Gaza barrages, major rioting and chaos erupt in Lod; Mayor: It's civil war". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "Arab politician warns Israel is 'on the brink of a civil war'". news.yahoo.com. 13 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "IDF enters Lod as city goes into emergency lockdown". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Schneider, Tal (11 May 2021). "Netanyahu declares state of emergency in Lod". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Jewish and Palestinian mobs dueled in Israeli towns — but the crackdown came for one side, Dalia Hatuqa, May 29 2021, The Intercept

- ^ Arab-Jewish coexistence in Israel suddenly ruptured, Isabel Kershner, May 13, 2021, The New York Times

- ^ ‘This is more than a reaction to rockets’: communal violence spreads in Israel, Peter Beaumont, Quique Kierszenbaum and Sufian Taha, 13 May 2021, The Guardian

- ^ Far-right Jewish groups and Arab youths claim streets of Lod as Israel loses control, Oliver Holmes and Quique Kierszenbaum, 15 May 2021, The Guardian

- ^ How Israeli police are colluding with settlers against Palestinian citizens, Oren Ziv, May 13, 2021, +972 Magazine

- ^ Palestine Exploration Fund, archive.org. Accessed 1 November 2022.

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics Annual Report 2010.

- ^ Neta Halperin, There's Art Outside of Tel Aviv, You Just Have to Look, Haaretz, 3 April 2012. Accessed 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Lod Mosaic tells nearly 2,000-year-old story from ancient Israel". Penn Today. 21 February 2013.

- ^ "Projects - Preservation". www.iaa-conservation.org.il.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ "Current Projects Archives". Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ "Piatra Neamţ – Twin Towns". Piatra Neamţ. Archived from the original on 16 November 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C. R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ISBN 978-0-86054-905-5.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gorzalczany, Amir; et al. (2016-05-09). "Lod, the Lod Mosaic" (128). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (p. 392)

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Holder, Meir (1986). History of the Jewish People From Yavne to Pumbedisa. ISBN 978-0-89906-499-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-866209-9.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-920405-41-4.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Monterescu, Daniel; Rabinowitz, Dan (2012). Mixed towns, trapped communities: historical narratives, spatial dynamics, gender relations and cultural encounters in Palestinian-Israeli towns (Illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-8746-3.

- ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Moudjir ed-dyn (1876). Sauvaire (ed.). Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine Under Muslim Rule. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 978-1-84171-821-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-39037-8.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (pp.49 −55)

- Rozenfeld, Ben Tsiyon (2010). Torah Centers and Rabbinic Activity in Palestine, 70–400 CE: History and Geographic Distribution. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17838-0.

- ISBN 978-0-231-13579-5.

- Shahin, Mariam (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. ISBN 978-1-56656-557-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-5352-0.

- ISBN 978-0-391-04155-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7146-5275-7.

- Thomson, W. M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

- Yacobi, Haim (2009). Goliath:The Jewish-Arab City: Spatio-politics in a mixed community. ISBN 978-1-134-06584-4.

- al-Ẓāhirī, Khalīl Ibn Shāhīn, Ghars al-Dīn Khalīl ibn Shāhīn (1894). Zoubdat kachf el-mamâlik: tableau politique et administratif de l'Égypte. E. Leroux.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- City council (in Hebrew)

- al-Lydd Palestine Remembered

- Lydda (Lod) Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Agency for Israel

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons