Music of Russia

| Music of Russia | ||||||||

| Genres | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific forms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Regional music | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Russia |

|---|

|

| Society |

|

| Topics |

|

| Symbols |

Music of Russia denotes

History

Early history

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

Written documents exist that describe the musical culture of the

In the time the

Secular music included the use of musical instruments such as

18th and 19th century: Russian classical music

Russia was a late starter in developing a native tradition of

The focus on European music meant that Russian composers had to write in Western style if they wanted their compositions to be performed. Their success at this was variable due to a lack of familiarity with European rules of composition. Some composers were able to travel abroad for training, usually to Italy, and learned to compose vocal and instrumental works in the Italian Classical tradition popular in the day. These include ethnic

The first great Russian composer to exploit native Russian music traditions into the realm of secular music was

Russian folk music became the primary source for the younger generation composers. A group that called itself "

This period also saw the foundation of the

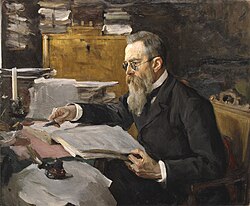

The late 19th and early 20th century saw the third wave of Russian classics:

In the late 19th to early 20th centuries, the so-called "

20th century: Soviet music

After the

However, in the 1930s, under the regime of

" and soon removed from theatres for years).The musical patriarchs of the era were

Film soundtracks produced a significant part of popular Soviet/Russian songs of the time, as well as of orchestral and experimental music. The 1930s saw Prokofiev's scores for

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Among the notable people of Soviet

The 1960s and 1970s saw the beginning of modern Russian pop and rock music. It started with the wave of

Music publishing and promotion in the Soviet Union was a state monopoly. To earn money and fame from their talent, Soviet musicians had to assign to the state-owned label Melodiya. This meant accepting certain boundaries of experimentation, that is, the family-friendly performance and politically neutral lyrics favoured by censors. Meanwhile, with the arrival of new sound recording technologies, it became possible for common fans to record and exchange their music via magnetic tape recorders. This helped underground music subculture (such as bard and rock music) to flourish despite being ignored by the state-owned media.[14]

"

Rock music came to the Soviet Union in the late 1960s with

21st century: modern Russian music

Russian pop music is well developed, and enjoys mainstream success via pop music media such as

Russian production companies, such as Hollywood World,[27] have collaborated with western music stars, creating a new, more globalized space for music.

The rock music scene has gradually evolved from the united movement into several different subgenres similar to those found in the West. There are youth

Rock music media has become prevalent in modern Russia.[

Other types of music include folk rock (

A specific, exclusively Russian kind of music has emerged, which mixes criminal songs, bard and romance music. It is labelled "Russian chanson" (a neologism popularized by its main promoter, Radio Chanson). Its main artists include Mikhail Krug, Mikhail Shufutinsky, and Alexander Rosenbaum. With lyrics about daily life and society, and frequent romanticisation of the criminal underworld, chanson is especially popular among adult males of the lower social class.[31][32]

Electronic music in modern Russia is underdeveloped in comparison to other genres.[

The profile of classical or concert hall music has to a considerable degree been eclipsed by on one hand the rise of commercial popular music in Russia, and on the other its own lack of promotion since the collapse of the USSR.[36] Yet a number of composers born in the 1950s and later have made some impact, notably Leonid Desyatnikov, who became the first composer in decades to have a new opera commissioned by the Bolshoi Theatre (The Children of Rosenthal, 2005), and whose music has been championed by Gidon Kremer and Roman Mints. Meanwhile, Gubaidulina, amongst several former-Soviet composers of her generation, continues to maintain a high profile outside Russia composing several prestigious and well-received works including "In tempus praesens" (2007) for the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter.

The early 2000s saw a boom of musicals in Russia.

2010s saw the rise of popularity of

Ethnic roots music

Russia today is a multi-ethnic state with over 100 ethnicities. Some of these ethnic groups has their own indigenous folk, sacred and in some cases art music, which can loosely be categorized together under the guise of ethnic roots music, or folk music. This category can further be broken down into folkloric (modern adaptations of folk material, and authentic presentations of ethnic music).

Adygea

In recent years,

Adygea's

Altay

Bashkir

The first major study of

The

Buryatia

The Buryats of the far east is known for distinctive folk music which uses the two-stringed horsehead fiddle, or morin khuur. The style has no polyphony and has little melodic innovation. Narrative structures are very common, many of them long epics which claim to be the last song of a famous hero, such as in the "Last Song of Rinchin Dorzhin". Modern Buryat musicians include the band Uragsha, which uniquely combines Siberian and Russian language lyrics with rock and Buryat folk songs, and Namgar, who is firmly rooted in the folk tradition but also explores connections to other musical cultures.

Chechnya

Alongside the Chechen rebellion of the 1990s came a resurgence in Chechen national identity, of which music is a major part. People like Said Khachukayev became prominent promoting Chechen music.

The Chechen

In April 2024, it was reported that Minister of Culture Musa Dadayev had been instructed by head of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov to restrict music to specific tempos to "conform to the Chechen mentality and sense of rhythm" by 1 June, banning any vocal, musical, or choreographic works not composed between 80 and 116 beats per minute (BPM).[37][38] Dadayev later stated that this was meant to be guidance for the performance of traditional melodies, and was not meant to be an outright ban.[39]

Dagestan

Karelia

Karelians are Finnish, and so much of their music is the same as Finnish music. The Kalevala is a very important part of traditional music; it is a recitation of Finnish legends, and is considered an integral part of the Finnish folk identity.

The Karelian Folk Music Ensemble is a prominent folk group.

Ossetia

Ossetians are people of the Caucasian Region, and thus Ossetian music and dance[40] have similar themes to the music of Chechnya and the music of Dagestan.

Russia

Archeology and direct evidence show a variety of

]Chastushkas are a kind of Russian folk song with a long history. They are typically humorous or satiric.

During the 19th century,

Sakha

Tatarstan

Tatar folk music has rhythmic peculiarities and pentatonic intonation in common with nations of the

).Tuva

Ukrainian music in Russia

Although Ukraine is an independent country since 1991, Ukrainians constitute the second-largest ethnic minority in Russia. The bandura is the most important and distinctive instrument of the Ukrainian folk tradition, and was used by court musicians in the various Tsarist courts. The kobzars, a kind of wandering performers who composed dumy, or folk epics.

Hardbass in Russia

Hardbass or hard bass (Russian: хардбасс, tr. hardbass, IPA: [xɐrdˈbas]) is a subgenre of electronic music which originated from Russia during the late 1990s, drawing inspiration from UK hard house, bouncy techno and hardstyle. Hardbass is characterized by its fast tempo (usually 150–175 BPM), donks, distinctive basslines (commonly known as "hard bounce"), distorted sounds, heavy kicks and occasional rapping. Hardbass has become a central stereotype of the gopnik subculture. In several European countries, so-called "hardbass scenes" have sprung up,[1] which are events related to the genre that involve multiple people dancing in public while masked, sometimes with moshing involved.

From 2015 onward, hardbass has also appeared as an Internet meme, depicting Slavic and Russian subcultures with the premiere of the video "Cheeki Breeki Hardbass Anthem", based on the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series of games from GSC game world.[2]

See also

- List of Russian composers

- Russian traditional music

References

Notes

- ^ РУССКИЕ МУЗЫКАЛЬНЫЕ ИНСТРУМЕНТЫ [Russian Musical Instruments]. soros.novgorod.ru (in Russian).

- ISBN 978-0-7546-3466-9

- ^ "Russian Music before Glinka". biu.ac.il.

- ^ "Интерфакты. Часть 6. Балалайка" [Interfacts. Part 6. Balalaika] (in Russian). Tomsk Regional State Philarmony. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ "Почему Алексей Михайлович приказал сжечь все балалайки" [Why did Alexei Mikhailovich order to burn all the balalaikas] (in Russian). Cyrillitsa.ru. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

Everyone knows about the witch hunt of Inquisition times, but only few people aware that in 17th century Russia there were burning balalaikas for the same purpose

- ^ Holden, xxi; Maes, 14.

- ^ Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 21:925

- ^ Maes, 14.

- ^ Bergamini, 175; Kovnatskaya, New Grove (2001), 22:116; Maes, 14.

- ^ Campbell, New Grove (2001), 10:3, Maes, 30.

- ^ Maes, 16.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-271-02369-4

- ISBN 978-0-415-54620-1

- ^ a b "History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre". russia-ic.com.

- ^ Walter Gerald Moss. A History Of Russia: Since 1855, Volume 2. Anthem Series on Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies. Anthem Press, 2004. 643 pages.

- JSTOR 960424.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (22 November 2000). "Perfect isn't good enough". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- JSTOR 25172838.

- JSTOR 965578.

- S2CID 191336167.

- JSTOR 965219.

- JSTOR 898239.

- ^ Berger, Arion (3 October 2002). "Album Reviews T.A.T.U.: 200 KM/H In The Wrong Lane". Rolling Stone. No. 906. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008.

- ^ "Uncharted Territory: Pomplamoose Enters Top 10, Friendly Fires Debut". Billboard.

- ^ "Billboard – Music Charts, Music News, Artist Photo Gallery & Free Video". Billboard.

- ^ "Serebro". billboard.com.

- ^ "[.m] masterhost – профессиональный хостинг сайта(none)". www.hollywoodworld.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Diverse Genres of Modern Music in Russia Archived 7 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Russia-Channel.com

- ^ The Moscow News – Chartova Dyuzhina[permanent dead link]

- ^ "A Russian Woodstock: Rock and Roll and Revolution?; Not for This Generation".[dead link]

- ^ Modern Russian History in the Mirror of Criminal Song Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine – An academic article

- ^ Notes From a Russian Musical Underground – A New York Times article about modern Russian Chanson

- ^ "44100hz ~ electronic music in Russia – Статья – Российская электронная музыка – общая ситуация". 44100.com.

- ^ "Russmus: ППК/PPK". russmus.net.

- ^ "DJ Groove". Far from Moscow.

- ^ See Richard Taruskin "Where is Russia's New Music?", reprinted in On Russian Music. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009: p. 381

- ^ Treisman, Rachel (9 April 2024). "Chechnya is banning music that's too fast or slow. These songs wouldn't make the cut". NPR.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Mchedlishvili, Luiza (15 April 2024). "Kadyrov says restrictions to music tempo were 'just recommendations'". OC Media. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- YouTube

Bibliography

- Bergamini, John, The Tragic Dynasty: A History of the Romanovs (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969). Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 68-15498.

- Campbell, James Stuart, "Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Hosking, Geoffrey, Russia and the Russians: A History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-674-00473-6.

- Kovnaskaya, Lyudmilla, "St Petersburg." In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London, Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Most favorite American and Russian Music Artists (Dec 2018) (July 2020).

- Ritzarev, Marina, Eighteenth-Century Russian Music (Ashgate, 2006). ISBN 978-0-7546-3466-9.

- Ritzarev, Marina, Tchaikovsky's Pathétique and Russian Culture (Ashgate, 2014). ISBN 978-1-4724-2412-9.

Further reading

- Broughton, Simon and Didenko, Tatiana. "Music of the People". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with Mark, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp 248–254. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0