Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War

| Polish–Lithuanian-Teutonic War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Battle of Grunwald (1878) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Allies: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Polish–Teutonic Wars | ||||||

The Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War, also known as the Great War, occurred between 1409 and 1411 between the

After the truce expired in June 1410, the military-religious monks were decisively defeated in the

However, the Knights never recovered their former power, and the financial burden of war reparations caused internal conflicts and economic decline in their lands. The war shifted the balance of power in Central Europe and marked the rise of the Polish–Lithuanian union as the dominant power in the region.[1]

Historical background

In 1230, the

In 1385, Grand Duke

History

Course of war

Uprising, war and truce

In May 1409, an uprising in Teutonic-held Samogitia started. Lithuania supported the uprising and the Knights threatened to invade. Poland announced its support for the Lithuanian cause and threatened to invade Prussia in return. As Prussian troops evacuated Samogitia, the Teutonic Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen declared war on the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania on 6 August 1409.[5] The Knights hoped to defeat Poland and Lithuania separately and began by invading Greater Poland and Kuyavia, catching the Poles by surprise.[6] The Knights burned the castle at Dobrin (Dobrzyń nad Wisłą), captured Bobrowniki after a fourteen-day siege, conquered Bydgoszcz (Bromberg), and sacked several towns.[7] The Poles organized counterattacks and recaptured Bydgoszcz.[8] The Samogitians attacked Memel (Klaipėda).[6] However, neither side was ready for a full-scale war.

Strategy and march in Prussia

By December 1409, Jogaila and Vytautas had agreed on a common strategy: their armies would unite into a single massive force and march together towards Marienburg (

The first stage of the Grunwald campaign was gathering all Polish–Lithuanian troops at

Battle of Grunwald

The

The Knights hoped to provoke Poles or Lithuanians to attack first and sent two swords, known as Grunwald Swords, to "assist Jogaila and Vytautas in battle".[24] Lithuanians attacked first, but after more than an hour of heavy fighting, the Lithuanian light cavalry started a full retreat.[25] The reason for the retreat – whether it was a retreat of the defeated force or a preconceived maneuver – remains a topic of academic debate.[26] Heavy fighting began between Polish and Teutonic forces and even reached the royal camp of Jogaila. One Knight charged directly against King Jogaila, who was saved by royal secretary Zbigniew Oleśnicki.[2] The Lithuanians returned to the battle. As Grand Master von Jungingen attempted to break through the Lithuanian lines, he was killed.[27] Surrounded and leaderless, the Teutonic Knights began to retreat towards their camp in hopes to organize a defensive wagon fort. However, the defense was soon broken and the camp was ravaged and according to an eyewitness account, more Knights died there than in the battlefield.[28]

The defeat of the Teutonic Knights was resounding. About 8,000 Teuton soldiers were killed[29] and an additional 14,000 were taken captive.[30] Most of the brothers of the Order were killed, including most of the Teutonic leadership. The highest-ranking Teutonic official to escape the battle was Werner von Tettinger, Komtur of Elbing (Elbląg).[30] Most of the captive commoners and mercenaries were released shortly after the battle on condition that they report to Kraków on 11 November 1410.[31] The nobles were kept in captivity and high ransoms were demanded for each.

Siege of Marienburg

After the battle, the Polish and Lithuanian forces delayed their attack on the Teutonic capital in Marienburg (Malbork) by staying on the battlefield for three days and then marching an average of only about 15 km (9.3 mi) per day.[32] The main forces did not reach heavily fortified Marienburg until 26 July. This delay gave Heinrich von Plauen enough time to organize a defense. Polish historian Paweł Jasienica speculated that this was likely an intentional move by Jagiełło, who together with Vytautas preferred to keep the humbled but not decimated Order in play as to not upset the balance of power between Poland (which would most likely acquire most of the Order possessions if it was totally defeated) and Lithuania; but a lack of primary sources precludes a definitive explanation.[33]

Jogaila, meanwhile, also sent his troops to other Teutonic fortresses, which often surrendered without resistance,

Aftermath

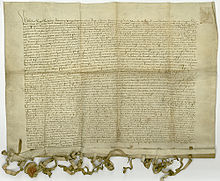

The

References

- ^ Ekdahl 2008, p. 175

- ^ a b c Stone 2001, p. 16

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 132

- ^ Kiaupa, Kiaupienė & Kuncevičius 2000, p. 137

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 20

- ^ a b Ivinskis 1978, p. 336

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 130

- ^ Kuczynski 1960, p. 614

- ^ Jučas 2009, p. 51

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 21

- ^ Kiaupa, Kiaupienė & Kuncevičius 2000, p. 139

- ^ Christiansen 1997, p. 227

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 30

- ^ a b c Jučas 2009, p. 75

- ^ Jučas 2009, p. 74

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 33

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 142

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 35

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 36–37

- ^ Urban 2003, pp. 148–149

- ^ Jučas 2009, p. 77

- ^ Jučas 2009, pp. 57–58

- ^ Разин 1999, pp. 485–486

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 43

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 45

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 48–49

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 64

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 66

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 157

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 68

- ^ Jučas 2009, p. 88

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 162

- ^ Paweł Jasienica (1978). Jagiellonian Poland. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 108–109.

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 164

- ^ Stone 2001, p. 17

- ^ Ivinskis 1978, p. 342

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 75

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 74

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 166

- ^ a b Christiansen 1997, p. 228

- ^ Kiaupa, Kiaupienė & Kuncevičius 2000, pp. 142–144

- ^ Christiansen 1997, pp. 228–230

- ^ Stone 2001, pp. 17–19

Bibliography

- Christiansen, Eric (1997), The Northern Crusades (2nd ed.), Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-026653-4

- Ekdahl, Sven (2008), "The Battle of Tannenberg-Grunwald-Žalgiris (1410) as reflected in Twentieth-Century monuments", in Victor Mallia-Milanes (ed.), The Military Orders: History and Heritage, vol. 3, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7546-6290-7

- Ivinskis, Zenonas (1978), Lietuvos istorija iki Vytauto Didžiojo mirties (in Lithuanian), Rome: Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademija, OCLC 464401774

- Jučas, Mečislovas (2009), The Battle of Grünwald, Vilnius: National Museum Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, ISBN 978-609-95074-5-3

- ISBN 9986-810-13-2

- Kuczynski, Stephen M. (1960), The Great War with the Teutonic Knights in the years 1409–1411, Ministry of National Defence, OCLC 20499549

- Разин, Е. А. (1999), История военного искусства XVI – XVII вв. (in Russian), vol. 3, Издательство Полигон, ISBN 5-89173-041-3

- ISBN 978-1-84176-561-7

- Stone, Daniel (2001), The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795, ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5

- ISBN 0-929700-25-2