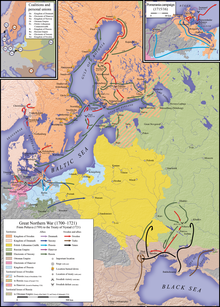

Great Northern War

| Great Northern War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northern Wars | |||||||||

From left to right: | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

Total: 200,000 dead

|

Total: 295,000 dead | ||||||||

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the

Charles XII led the Swedish army. Swedish allies included

The war began when an alliance of

After Poltava, the anti-Swedish coalition revived and subsequently Hanover and Prussia joined it. The remaining Swedish forces in

The war ended with the defeat of Sweden, leaving Russia as the new dominant power in the Baltic region and as a new major force in European politics. The Western powers,

Background

Between 1560 and 1658,

However, the Swedish state ultimately proved unable to support and maintain its army in a prolonged war. Campaigns on the continent had been proposed on the basis that the army would be financially self-supporting through plunder and taxation of newly gained land, a concept shared by most major powers of the period. The cost of the warfare proved to be much higher than the occupied countries could fund, and Sweden's coffers and resources in manpower were eventually drained in the course of long conflicts.

The foreign interventions in Russia during the Time of Troubles resulted in Swedish gains in the Treaty of Stolbovo (1617). The treaty deprived Russia of direct access to the Baltic Sea. Russian fortunes began to reverse in the final years of the 17th century, notably with the rise to power of Peter the Great, who looked to address the earlier losses and re-establish a Baltic presence. In the late 1690s, the adventurer Johann Patkul managed to ally Russia with Denmark and Saxony by the secret Treaty of Preobrazhenskoye, and in 1700 the three powers attacked.

Opposing parties

Swedish camp

Allied camp

Frederick IV of Denmark-Norway, another cousin of Charles XII,[nb 1] succeeded Christian V in 1699 and continued his anti-Swedish policies. After the setbacks of 1700, he focused on transforming his state, an absolute monarchy, in a manner similar to Charles XI of Sweden. He did not achieve his main goal: to regain the former eastern Danish provinces lost to Sweden in the course of the 17th century. He was not able to keep northern Swedish Pomerania, Danish from 1712 to 1715. He did put an end to the Swedish threat south of Denmark. He ended Sweden's exemption from the Sound Dues (transit taxes/tariffs on cargo moved between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea).

George I of the House of Hanover, elector of Hanover and, since 1714, king of Great Britain and of Ireland, took the opportunity to connect his landlocked German electorate to the North Sea.

Army size

In 1700,

Russia was able to mobilize a larger army but could not put all of it into action simultaneously. The Russian mobilization system was ineffective and the expanding nation needed to be defended in many locations. A grand mobilization covering Russia's vast territories would have been unrealistic. Peter I tried to raise his army's morale to Swedish levels. Denmark contributed 20,000 men in their invasion of Holstein-Gottorp and more on other fronts. Poland and Saxony together could mobilize at least 100,000 men.

| Type | Sweden[20][21][22] | Russia[23][24][25] | Denmark-Norway[26] | Poland-Lithuania[27] | Saxony**[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| infantry | 1,900 life guards

33,456 musketeers 19,584 pikemen 6,528 grenadiers 8,400 militia |

49,400 line infantry | 27,600 line infantry

1,200 naval infantry 1,540 grenadiers 9,600 militia (768 grenadiers) |

2,000 line infantry

150 halberdiers |

22,500 line infantry

1,500 grenadiers |

| heavy/line

cavalry |

1,500 mounted lifeguard

100 Horse drabants 15,000 heavy cavalry 1,800 noble cavalry |

11,553 noble cavalry | 402 life guards

402 horse guards 57 drabant guard 4,556 line cavalry |

2,100 winged hussars

2,800 pancerni 2,200 heavy cavalry |

900 Garde du Corps

1,800 cuirassiers |

| other cavalry* | 10,000 dragoons

4,000 baltic militia dragoons |

1,798 dragoons

20,000 Ukrainian cossacks 15,000 Zaporozhian cossacks 15,000 Don Cossacks |

7,504 dragoons

804 militia dragoons |

4,000 dragoons

1,710 light cavalry |

unspecified amount of dragoons |

| Total | 69,868 infantry

32,400 cavalry |

49,400 infantry

63,351 cavalry |

39,940 infantry

13,723 cavalry |

2,150 infantry

12,810 cavalry |

* The difference between heavy and other cavalry is often unclear as Swedish cavalry was used as heavy shock cavalry yet was unarmoured.

** The Saxon army and corresponding militia does not have full details available.

| Size of European armies in 1710 | ||

| Population ~1650 (millions) | Size of Army (thousands) | |

| State | Size | ~1710 |

|---|---|---|

| Denmark–Norway | 1.3 [29] | 53 [30] |

| Swedish Empire | 1.1 [29] | 100 [31] |

| Brandenburg-Prussia | 0.5 [32] | 40 [33] |

| Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth | 11 [34] | 100* [35] |

| Tsardom of Russia | 15 [36] | 170 [31] |

| Kingdom of England | 4.7 [37] | 87 [31] |

| Dutch Republic | 1.5 [38] | 120 [39] |

| Kingdom of France | 18 [40] | 340–380 [39] |

Habsburg Monarchy |

8 [41] | 110–130 [41] |

| Crown of Castile Crown of Aragon |

7 [40] | 50 [31] |

| Ottoman Empire | 18 [42] | 50** [43] |

| * All Polish forces, on both sides in the Great Northern War. | ** Janissaries only.

| |

1700: Denmark, Riga and Narva

Charles XII was now able to speedily deploy his army to the eastern coast of the

After the dissolution of the first coalition through the

1701–1706: Poland-Lithuania and Saxony

Charles XII then turned south to meet

1702–1710: Russia and the Baltic provinces

The

The Nyen fortress was soon abandoned and demolished by Peter, who built nearby a superior fortress as a beginning to the city of Saint Petersburg. By 1704, other fortresses were situated on the island of Kotlin and the sand flats to its south. These became known as Kronstadt and Kronslot.[52] The Swedes attempted a raid on the Neva fort on 13 July 1704 with ships and landing armies, but the Russian fortifications held. In 1705, repeated Swedish attacks were made against Russian fortifications in the area, to little effect. A major attack on 15 July 1705 ended in the deaths of more than 500 Swedish men, or a third of its forces.[53]

In view of continued failure to check Russian consolidation, and with declining manpower, Sweden opted to blockade Saint Petersburg in 1705. In the summer of 1706, Swedish General

In August 1708, a Swedish army of 12,000 men under General

Charles spent the years 1702–06 in a prolonged struggle with

At this point, in 1707, Peter offered to return everything he had so far occupied (essentially Ingria) except Saint Petersburg and the line of the Neva,

This shattering defeat in 1709 did not end the war, although it decided it. Denmark and Saxony joined the war again and Augustus the Strong, through the politics of Boris Kurakin, regained the Polish throne.[61] Peter continued his campaigns in the Baltics, and eventually he built up a powerful navy. In 1710 the Russian forces captured Riga,[62] at the time the most populated city in the Swedish realm, and Tallinn, evicting the Swedes from the Baltic provinces, now integrated in the Russian Tsardom by the capitulation of Estonia and Livonia.

Formation of a new anti-Swedish alliance

After Poltava, Peter the Great and Augustus the Strong allied again in the Treaty of Thorn (1709); Frederick IV of Denmark-Norway with Augustus the Strong in the Treaty of Dresden (1709); and Russia with Denmark–Norway in the subsequent Treaty of Copenhagen. In the Treaty of Hanover (1710), Hanover, whose elector was to become George I of Great Britain, allied with Russia. In 1713, Brandenburg-Prussia allied with Russia in the Treaty of Schwedt. George I of Great Britain and Hanover concluded three alliances in 1715: the Treaty of Berlin with Denmark–Norway, the Treaty of Stettin with Brandenburg-Prussia, and the Treaty of Greifswald with Russia.

1709–1714: Ottoman Empire

When his army surrendered, Charles XII of Sweden and a few soldiers escaped to

1710–1721: Finland

The war between Russia and Sweden continued after the disaster of

After the failure of 1712, Peter the Great ordered that further campaigns in war-ravaged regions of Finland with poor transportation networks were to be performed along the coastline and the seaways near the coast. Alarmed by the Russian preparations Lybecker requested naval units to be brought in as soon as possible in the spring of 1713. However, like so often, Swedish naval units arrived only after the initial Russian spring campaign had ended.[68] Nominally under the command of Apraksin, but accompanied by Peter the Great, a fleet of coastal ships together with 12,000 men—infantry and artillery—began the campaign by sailing from Kronstadt on 2 May 1713; a further 4,000 cavalry were later sent overland to join with the army. The fleet had already arrived at Helsinki on 8 May and were met by 1,800 Swedish infantry under General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt, which started the Battle of Helsinki.[69] Together with rowers from the ships the Russians had 20,000 men at their disposal even without the cavalry. The defenders, however, managed to fend off landing attempts by the attackers until the Russians landed at their flank at Sandviken, which forced Armfelt to retire towards Porvoo (Borgå) after setting afire both the town and all the supplies stored there as well as bridges leading north from the town. It was only on 12 May that a Swedish squadron under Admiral Erik Johan Lillie made it to Helsinki but there was nothing it could do.[70]

The bulk of the Russian forces moved along the coast towards Borgå and the forces of Lybecker, whom Armfelt had joined. On 21–22 May 1713 a Russian force of 10,000 men landed at Pernå (Pernaja) and constructed fortifications there. Large stores of supplies and munitions were transported from Viborg and Saint Petersburg to the new base of operations. Russian cavalry managed to link up with the rest of the army there as well. Lybecker's army of 7000 infantry and 3000 cavalry avoided contact with the Russians and instead kept withdrawing further inland without even contesting the control of Borgå region or the important coastal road between Helsinki (Helsingfors) and Turku (Åbo). This also severed the contact between Swedish fleet and ground forces and prevented Swedish naval units from supplying it. Soldiers in the Swedish army who were mostly Finnish resented being repeatedly ordered to withdraw without even seeing the enemy. Lybecker was soon recalled to Stockholm for a hearing and Armfelt was ordered to the command of the army. Under his command the Swedish army in Finland stopped to engage the advancing Russians at Pälkäne in October 1713, where a Russian flanking manoeuvre forced him to withdraw to avoid getting encircled. The armies met again later at Napue in February 1714, where the Russians won a decisive victory.[71]

In 1714, far greater Swedish naval assets were diverted towards Finland, which managed to cut the coastal sea route past

1710–1716: Sweden and Northern Germany

In 1710, the Swedish army in Poland retreated to Swedish Pomerania, pursued by the coalition. In 1711, siege was laid to Stralsund. Yet the town could not be taken due to the arrival of a Swedish relief army, led by general Magnus Stenbock, which secured the Pomeranian pocket before turning west to defeat an allied army in the Battle of Gadebusch. Pursued by coalition forces, Stenbock and his army was trapped and surrendered during the Siege of Tönning.[73]

In 1714, Charles XII returned from the Ottoman Empire, arriving in

1716–1718: Norway

After Charles XII had returned from the Ottoman Empire and resumed personal control of the war effort, he initiated two

1719–1721: Sweden

After the death of Charles XII, Sweden still refused to make peace with Russia on Peter's terms. Despite a continued Swedish naval presence and strong patrols to protect the coast, small Russian raids took place in 1716 at Öregrund, while in July 1717 a Russian squadron landed troops at Gotland who raided for supplies. To place pressure on Sweden, Russia sent a large fleet to the Swedish east coast in July 1719. There, under protection of the Russian battlefleet, the Russian galley fleet was split into three groups. One group headed for the coast of Uppland, the second to the vicinity of Stockholm, and the last to coast of Södermanland. Together they carried a landing force of nearly 30,000 men. Raiding continued for a month and devastated amongst others the towns of Norrtälje, Södertälje, Nyköping and Norrköping, and almost all the buildings in the archipelago of Stockholm were burned. A smaller Russian force advanced on the Swedish capital but was stopped at the battle of Stäket on 13 August. Swedish and British fleets, now allied with Sweden, sailed from the west coast of Sweden but failed to catch the raiders.[78]

After the treaty of Frederiksborg in early 1720, Sweden was no longer at war with Denmark, which allowed more forces to be placed against the Russians. This did not prevent Russian galleys from raiding the town of Umeå once again. Later, in July 1720, a squadron from the Swedish battlefleet engaged the Russian galley fleet in the battle of Grengam. While the result of the battle is contested, it ended Russian galley raids in 1720. As negotiations for peace did not progress, the Russian galleys were once again sent to raid the Swedish coast in 1721, targeting primarily the Swedish coast between Gävle and Piteå.[79]

Peace

By the time of Charles XII's death, the anti-Swedish allies became increasingly divided on how to fill the power gap left behind by the defeated and retreating Swedish armies. George I and Frederik IV both coveted hegemony in northern Germany, while Augustus the Strong was concerned about the ambitions of Frederick William I on the southeastern Baltic coast. Peter the Great, whose forces were spread all around the Baltic Sea, envisioned hegemony in East Central Europe and sought to establish naval bases as far west as Mecklenburg. In January 1719, George I, Augustus and emperor Charles VI concluded a treaty in Vienna aimed at reducing Russia's frontiers to the pre-war limits.[77]

Hanover-Great Britain and Brandenburg-Prussia thereupon negotiated separate peace treaties with Sweden, the treaties of Stockholm in 1719 and early 1720, which partitioned Sweden's northern German dominions among the parties. The negotiations were mediated by French diplomats, who sought to prevent a complete collapse of Sweden's position on the southern Baltic coast and assured that Sweden was to retain Wismar and northern Swedish Pomerania. Hanover gained Swedish Bremen-Verden, while Brandenburg-Prussia incorporated southern Swedish Pomerania.[80] Britain would briefly switch sides and supported Sweden before leaving the war. In addition to the rivalries in the anti-Swedish coalition, there was an inner-Swedish rivalry between Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, and Frederick I of Hesse-Cassel for the Swedish throne. The Gottorp party succumbed and Ulrike Eleonora, wife of Frederick I, transferred power to her husband in May 1720. When peace was concluded with Denmark, the anti-Swedish coalition had already fallen apart, and Denmark was not in a military position to negotiate a return of its former eastern provinces across the sound. Frederick I was, however, willing to cede Swedish support for his rival in Holstein-Gottorp, which came under Danish control with its northern part annexed, and furthermore cede the Swedish privilege of exemption from the Sound Dues. A respective treaty was concluded in Frederiksborg in June 1720.[80]

When Sweden finally was at peace with Hanover, Great Britain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark–Norway, it hoped that the anti-Russian sentiments of the Vienna parties and France would culminate in an alliance that would restore its Russian-occupied eastern provinces. Yet, primarily due to internal conflicts in Great Britain and France, that did not happen. Therefore, the war was finally concluded by the Treaty of Nystad between Russia and Sweden in Uusikaupunki (Nystad) on 30 August 1721 (OS). Finland was returned to Sweden, while the majority of Russia's conquests (Swedish Estonia, Livonia, Ingria, Kexholm and a portion of Karelia) were ceded to the tsardom.[81] Sweden's dissatisfaction with the result led to fruitless attempts at recovering the lost territories in the course of the following century, such as the Russo-Swedish War of 1741–1743, and the Russo-Swedish War of 1788–1790.[80]

Saxe-Poland-Lithuania and Sweden did not conclude a formal peace treaty; instead, they renewed the

Sweden had lost almost all of its "overseas" holdings gained in the 17th century and ceased to be a major power. Russia gained its Baltic territories and became one of the greatest powers in Europe.

See also

- Caroleans

- Military of the Swedish Empire

- Swedish army

References

Notes

- ^ Frederik III of Denmark-Norway

Citations

- ^ Larsson 2009, p. 78

- ^ Liljegren 2000

- ^ From 2007, p. 214

- ^ A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the War in Chechnya, David R. Stone. Greenwood Publishing Group (2006). p. 57.

- ^ From 2007, p. 240

- ^ ISBN 978-91-1-303042-5

- ^ a b Grigorjev & Bespalov 2012, p. 52

- ^ Höglund & Sallnäs 2000, p. 51

- ^ Józef Andrzej Gierowski – Historia Polski 1505–1764 (History of Poland 1505–1764), pp. 258–261

- ^ "Tacitus.nu, Örjan Martinsson. Danish force". Tacitus.nu. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Höglund & Sallnäs 2000, p. 132

- ^ Ericson, Lars, Svenska knektar (2004) Lund: Historiska media[page needed]

- ISBN 978-952-234-638-4.

- ^ Урланис Б. Ц. (1960). Войны и народонаселение Европы. Moscow: Изд-во соц.-экон. лит-ры. p. 55.

- ^ Pitirim Sorokin "Social and Cultural Dynamics, vol.3"

- ^ Lindegren, Jan, Det danska och svenska resurssystemet i komparation (1995) Umeå : Björkås : Mitthögsk[page needed]

- ^ a b Gosse 1911, p. 206.

- ^ Gosse 1911, p. 216.

- ^ Richard Brzezinski. Lützen 1632: Climax of the Thirty Years' War. Osprey Publishing, 2001. p. 19

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ISBN 978-1-85532-348-3.

- ISBN 978-1-85532-315-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-3349-5.

- ^ a b Ladewig-Petersen, E. (1999). "Nyt om trediveårskrigen." Historisk Tidsskrift., p. 101.

- ^ Petersen, Nikolaj Pilgård (2002). Hærstørrelse og fortifikationsudvikling i Danmark-Norge 1500–1720. Aarhus universitet: Universitetsspeciale i historie, pp. 11, 43–44.

- ^ a b c d Parker, Geoffrey (1976). "The 'Military Revolution', 1560–1660 – a myth?". Journal of modern history, vol. 48, p. 206.

- ^ "Population of Germany." Tacitus.nu. Archived 28 June 2004 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ Craig, Gordon A. (1964). The Politics of the Prussian Army: 1640–1945. London: Oxford University Press, p. 7.

- ^ "Population of Central Europe." Tacitus.nu. Archived 12 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J. (2008), Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715. London: Greenwood Press, pp. 368–369.

- ^ "Population of Eastern Europe." Tacitus.nu. Archived 8 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ "Population of the British Isles." Tacitus.nu. Archived 2 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ "The Netherlands." Population statistics. Archived 26 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ a b Glete, Jan (2002). War and the State in Early Modern Europe. London : Routledge, p. 156.

- ^ a b "Population of Western Europe." Tacitus.nu. Archived 1 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ a b Hochedlinger, Michael (2003). Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683–1797. London: Routledge, pp. 26, 102.

- ^ "Population of Eastern Balkans." Tacitus.nu. Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ^ Ágoston, Gabor (2010), "Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry and military transformation." In: Tallet, Frank & Trim, D.B.J. (eds.). European Warfare, 1350–1750. Cambridge University Press, p. 128.

- ^ Frost 2000, pp. 227–228

- ^ Frost 2000, pp. 228–229

- ^ a b Frost 2000, p. 229

- ^ Frost 2000, p. 230

- ^ Gosse 1911, p. 205.

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 694

- ^ a b Tucker 2010, p. 701

- ^ Frost 2000, pp. 230, 263ff

- ^ a b Tucker 2010, p. 691

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 10–19.

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 20–27.

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 700

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 703

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 707

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 704

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 706

- ^ Frost 2000, pp. 231, 286ff

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 710

- ^ Tucker 2010, p. 711

- ^ Petersen (2007), pp. 268–272, 275; Bengtsson (1960), pp. 393ff, 409ff, 420–445

- ^ The Russian Victory at Gangut (Hanko), 1714 by Maurice Baquoi, etched 1724

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 27–31.

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Mattila (1983), p. 30.

- ^ Mattila (1983), p. 33.

- ISBN 978-952-222-675-4.

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 33–35.

- ^ Mattila (1983), p. 35.

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 38–46.

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 140

- ^ Torke 2005, p. 165

- ^ Meier 2008, p. 23

- ^ North 2008, p. 53

- ^ a b Frost 2000, pp. 295–296

- ^ Mattila (1983), p. 47.

- ^ Mattila (1983), pp. 48–51.

- ^ a b c Frost 2000, p. 296

- ^ Rambaud, Arthur (1890). Recueil des instructions données aux ambassadeurs et ministres de France depuis les traités de Westphalie jusqu'à la Révolution française. Paris: Ancienne Librairie Germer Baillière et Cie. p. 232.

- ^ Donnert 1997, p. 510

Bibliography

- Bengtsson, Frans Gunnar(1960). The sword does not jest. The heroic life of King Charles XII of Sweden. St. Martin's Press.

- Donnert, Erich (1997). Europa in der Frühen Neuzeit: Festschrift für Günter Mühlpfordt. Aufbruch zur Moderne (in German). Vol. 3. Böhlau. ISBN 3-412-00697-1.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gosse, Edmund (1911). "Sweden". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 188–221.

- From, Peter (2007). Katastrofen vid Poltava – Karl XII:s ryska fälttåg 1707–1709 [The disaster at Poltava – Charles XII's Russian campaign 1707–1709] (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-85377-70-1.

- ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- Grigorjev, Boris; Bespalov, Aleksandr (2012). Kampen mot övermakten. Baltikums fall 1700–1710 [The fight against the supremacy. Fall of the Baltics 1700–1710.] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Svenskt militärhistoriskt bibliotek. ISBN 978-91-85653-52-2.

- Höglund, Lars-Eric; Sallnäs, Åke (2000). The Great Northern War, 1700–1721: Colours and Uniforms.

- Larsson, Olle (2009). Stormaktens sista krig [Last war of the great power] (in Swedish). ISBN 978-91-85873-59-3.

- Liljegren, Bengt (2000). Karl XII: en biografi [Charles XII: a biography] (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 91-89442-65-2.

- Mattila, Tapani (1983). Meri maamme turvana [Sea safeguarding our country] (in Finnish). Jyväskylä: K. J. Gummerus Osakeyhtiö. ISBN 951-99487-0-8.

- Meier, Martin (2008). Vorpommern nördlich der Peene unter dänischer Verwaltung 1715 bis 1721. Aufbau einer Verwaltung und Herrschaftssicherung in einem eroberten Gebiet. Beiträge zur Militär- und Kriegsgeschichte (in German). Vol. 65. Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 978-3-486-58285-7.

- North, Michael (2008). Geschichte Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns. Beck Wissen (in German). Vol. 2608. CH Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-57767-3.

- Peterson, Gary Dean (2007). Warrior kings of Sweden. The rise of an empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2873-1.

- Torke, Hans-Joachim (2005). Die russischen Zaren 1547–1917 (in German) (3 ed.). C.H.Beck. ISBN 3-406-42105-9.

- Tucker, S.C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict, Vol. Two. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

- Wilson, Peter Hamish (1998). German armies. War and German politics, 1648–1806. Warfare and history. Routledge. ISBN 1-85728-106-3.

Further reading

- Bain, R. Nisbet. Charles XII and the Collapse of the Swedish Empire, 1682–1719 (1899) online

- Englund, Peter. Battle That Shook Europe: Poltava & the Birth of the Russian Empire (2003)

- Hatton, Ragnhild M. "Charles XII and the Great Northern War." in J.S. Bromley, ed., New Cambridge Modern History VI: The Rise of Great Britain and Russia 1688–1725 (1970) pp 648–80.

- Lisk, Jill. The struggle for supremacy in the Baltic, 1600–1725 (1968).

- Lunde, Henrik O. A Warrior Dynasty: The Rise and Decline of Sweden as a Military Superpower (Casemate, 2014).

- McKay, Derek, and H. M. Scott. The Rise of the Great Powers 1648–1815 (1983) pp 77–93.

- Moulton, James R. Peter the Great and the Russian Military Campaigns During the Final Years of the Great Northern War, 1719–1721 (University Press of America, 2005).

- Oakley, Stewart P. War and Peace in the Baltic, 1560–1790 (Routledge, 2005).

- Sumner, B. H. (1951). Peter the Great and the Emergence of Russia. The English Universities Press Ltd.

- Stiles, Andrina. Sweden and the Baltic 1523–1721 (Hodder & Stoughton, 1992).

- Wilson, Derek. "Poltava: The battle that changed the world." History Today 59.3 (2009): 23.

Other languages

- Baskakov, Benjamin I. (1890) (in Russian). The Northern War of 1700–1721. Campaign from Grodno to Poltava 1706–1709 at formats

- Querengässer, Alexander (2019). Das kursächsische Militär im Großen Nordischen Krieg 1700–1717 (in German). Ferdinand Schöningh. ISBN 978-3-506-78871-9.

- Voltaire (1748). Anecdotes sur le Czar Pierre le Grand (in French) (Edition of 1820 ed.). E. A. Lequien, Libraire.

- Voltaire (1731). Histoire de Charles XII (in French) (Edition of 1879 ed.). Garnier.