Siege of Trichinopoly (1743)

| Siege of Trichinopoly (1743) | |

|---|---|

Trichinopoly, modern-day Tamil Nadu, India 10°48′18″N 78°41′08″E / 10.80500°N 78.68556°E | |

| Result |

Nizam victory Nizam army captures Trichinopoly. |

4,000 sepoy

200,000 sepoy

150 war elephants

200 artillery pieces

The Siege of Trichinopoly (14 March 1743 – 29 August 1743) was part of an extended series of conflicts between the

Background

In 1714, the

Under the influence of the Nizam's opponents, Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah issued a decree to Mubariz Khan, the governor of Hyderabad, to prevent the Nizam from taking the Deccan province under his control. Nizam and Mubariz Khan confronted each other at Shaker Kheda (a valley in present-day Buldhana district, Berar Subah, 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Aurangabad), resulting in the Battle of Shakar Kheda. On 11 October 1724, the Nizam defeated and killed Mubariz Khan, establishing autonomous rule over the Deccan region. The Nizam remained loyal to the Mughal Emperor, did not assume any imperial title, and continued to acknowledge Mughal suzerainty.[1]: 93–94 The region was renamed Hyderabad Deccan, beginning what is known as the Asaf Jahi dynasty. The Nizam retained the title of "Nizam ul-Mulk", and was referred to as "Asaf Jahi Nizam", or more commonly, the Nizam of Hyderabad.[4]: 241–260 [5][6] He acquired de facto control over the Deccan and thus all six Mughal governorates became his feudatory.[7]: 98 [8]: 298–310

In the 1720s, the Carnatic region of

This decisive act and the refusal of tributary payment by Dost Ali Khan enraged the Marathas. They took advantage of the absence of the Nizam in Deccan due to his engagement in resolving disputes in North India. In 1740,

Prelude

In 1741, the Nizam had just returned from

In 1742, the Nizam, who was busy with the affairs in Delhi, returned to the Deccan. After the

Siege

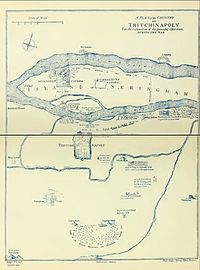

After deposing Muhammed Saadatullah Khan II in Arcot, the Nizam marched towards Trichinopoly. On 14 March 1743, Nizam arrived at Trichinopoly with a large army of 200,000

Murari Rao could not expect any help from his Maratha superiors, as

As per the agreement of Trichinopoly, if

Aftermath

When the Nizam took control of Trichinopoly in September 1743,

From 1744 to 1746, two expeditions were sent by Maratha Emperor Shahu I to expand the Maratha supremacy over the Carnatic region. Babuji Naik of

The subsequent

: 137See also

- Anglo-Maratha Wars

- Carnatic Wars

- Nizams of Hyderabad

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ISBN 978-0-231-80042-6.

- ^ a b Nathanael, M. P. (6 August 2016). "Treasures of Trichy". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- S2CID 142989123.

- ISBN 978-0-231025-80-5. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Rao, Sushil (11 December 2009). "Testing time again for the pearl of Deccan". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-247867-35-9. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-011544-27-1. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ JSTOR 44303889.

- ISBN 978-8-131300-34-3.

- ISBN 978-8-120614-82-6. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-8-170221-95-1. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-8-120618-89-3. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-8-120618-89-3. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- JSTOR 41688690. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-836412-62-8. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society (Bangalore)". 89. University of Michigan. 1998. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Alalasundaram, R. (1998). "The Colonial World of Ananda Ranga Pillai, 1736-1761: A Classified Compendium of His Diary". University of Michigan. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Beveridge, Henry (2008). A Comprehensive History of India, Civil, Military, and Social, from the First Landing of the English to the Suppression of the Sepoy Revolt:Including an Outline of the Early History of Hindoostan. Vol. 2. Harvard University. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Rao, V. N. Hari (1961). Kōil Ol̤ugu: The Chronicle of the Srirangam Temple with Historical Note. Vol. 2. Rochouse. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ The Muslim Review. Vol. 1–2. University of Minnesota. 1926. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Kalarani, B S (2018). "A history of the travancore thirunelveli relation of the 18th century" (PDF). Manonmaniam Sundaranar University (Department of History). Retrieved 17 September 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 978-0-313335-39-6. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-8-120601-61-1. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Baskaran, N. (2012). Expansion of British Power in Tamil Country 1751 1801 (Thesis). Vol. 2. Presidency College, Chennai, University of Madras. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- hdl:10603/92519. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-8-120603-99-8.

- ISBN 978-1-44385-120-6. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- CUP Archive. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-843311-52-2.

- ISBN 978-8-171565-21-4. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-521891-03-5. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-8183794-68-8. Retrieved 12 August 2020.