User:OnBeyondZebrax/sandbox/Manhattan

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

tember 11, 2001===

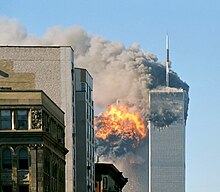

On September 11, 2001, two of four hijacked planes were flown into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. The towers collapsed. The 7 World Trade Center was not struck by a plane, but collapsed because of heavy debris falling from the impacts of planes and the collapse of the Twin Towers. The other buildings of the World Trade Center complex were damaged beyond repair and soon after demolished. The collapse of the Twin Towers caused extensive damage to surrounding buildings and skyscrapers in Lower Manhattan, and resulted in the deaths of 2,606 people, in addition to those on the planes. Since September 11, most of Lower Manhattan has been restored. However, many rescue workers and residents of the area developed several life-threatening illnesses and some have already died.[1]

Occupy Wall Street protests beginning in September 2011

The

Hurricane Sandy in October 2012

On October 29 and 30, 2012,

Geography

Description

Manhattan Island

Manhattan is loosely divided into Downtown (

Marble Hill

One neighborhood of New York County is contiguous with the mainland.

Marble Hill is one example of how Manhattan's land has been considerably altered by human intervention. The borough has seen substantial land reclamation along its waterfronts since Dutch colonial times, and much of the natural variation in topography has been evened out.[11]

Early in the 19th century,

Geology

Bedrock

The bedrock underlying much of Manhattan is a mica schist known as Manhattan Schist. It is a strong, competent metamorphic rock created when Pangaea formed. It is well suited for the foundations of tall buildings. In Central Park, outcrops of Manhattan Schist occur and Rat Rock is one rather large example.[16][17][18]

Geologically, a predominant feature of the substrata of Manhattan is that the underlying bedrock base of the island rises considerably closer to the surface near Midtown Manhattan, dips down lower between 29th Street and Canal Street, then rises toward the surface again in Lower Manhattan. It has been widely believed that the depth to bedrock was the primary underlying reason for the clustering of skyscrapers in the Midtown and Financial District areas, and their absence over the intervening territory between these two areas, as skyscrapers must have their foundations sunk into solid bedrock.[19][20][21] However, new research has shown that economic factors played a bigger part in the locations of these skyscrapers.[22][23][24]

Updated seismic analysis

According to the

Locations

Adjacent counties

- Bergen County, New Jersey—west/northwest

- Hudson County, New Jersey—west/southwest

- Bronx County, New York (The Bronx)—northeast

- Queens County, New York (Queens)—east/southeast

- Kings County, New York (Brooklyn)—south/southeast

- Richmond County, New York (Staten Island)—southwest

National protected areas

- African Burial Ground National Monument

- Castle Clinton National Monument

- Federal Hall National Memorial

- General Grant National Memorial

- Governors Island National Monument

- Hamilton Grange National Memorial

- Lower East Side Tenement National Historic Site

- Statue of Liberty National Monument (part)

- Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site

Neighborhoods

Manhattan's many neighborhoods are not named according to any particular convention. Some are geographical (the

Some neighborhoods, such as

In Manhattan, uptown means north (more precisely north-northeast, which is the direction the island and its street grid system is oriented) and downtown means south (south-southwest).[37] This usage differs from that of most American cities, where downtown refers to the central business district. Manhattan has two central business districts, the Financial District at the southern tip of the island, and Midtown Manhattan. The term uptown also refers to the northern part of Manhattan above 72nd Street and downtown to the southern portion below 14th Street,[38] with Midtown covering the area in between, though definitions can be rather fluid depending on the situation.

-

Public housing in the foreground in the Lower East Side

-

"Korea Way" on32nd Street in Manhattan's Koreatown (맨해튼 코리아타운)

-

The Upper West Side

Climate

Under the

Temperature records have been set as high as 106 °F (41 °C) on July 9, 1936, and as low as −15 °F (−26 °C) on February 9, 1934.

Summer evening temperatures are elevated by the urban heat island effect, which causes heat absorbed during the day to be radiated back at night, raising temperatures by as much as 7 °F (4 °C) when winds are slow.[44]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.4 (15.8) |

60.7 (15.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

82.9 (28.3) |

88.5 (31.4) |

92.1 (33.4) |

95.7 (35.4) |

93.4 (34.1) |

89.0 (31.7) |

79.7 (26.5) |

70.7 (21.5) |

62.9 (17.2) |

97.0 (36.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.5 (4.2) |

42.2 (5.7) |

49.9 (9.9) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

79.7 (26.5) |

84.9 (29.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

76.2 (24.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

44.3 (6.8) |

62.6 (17.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.7 (0.9) |

35.9 (2.2) |

42.8 (6.0) |

53.7 (12.1) |

63.2 (17.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

77.5 (25.3) |

76.1 (24.5) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.9 (14.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

39.1 (3.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

35.8 (2.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

55.0 (12.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

70.1 (21.2) |

68.9 (20.5) |

62.3 (16.8) |

51.4 (10.8) |

42.0 (5.6) |

33.8 (1.0) |

48.9 (9.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.8 (−12.3) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

43.9 (6.6) |

52.7 (11.5) |

61.8 (16.6) |

60.3 (15.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

38.4 (3.6) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

7.7 (−13.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

−15 (−26) |

3 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

32 (0) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

5 (−15) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.64 (92) |

3.19 (81) |

4.29 (109) |

4.09 (104) |

3.96 (101) |

4.54 (115) |

4.60 (117) |

4.56 (116) |

4.31 (109) |

4.38 (111) |

3.58 (91) |

4.38 (111) |

49.52 (1,258) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.8 (22) |

10.1 (26) |

5.0 (13) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.5 (1.3) |

4.9 (12) |

29.8 (76) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 125.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 11.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%)

|

61.5 | 60.2 | 58.5 | 55.3 | 62.7 | 65.2 | 64.2 | 66.0 | 67.8 | 65.6 | 64.6 | 64.1 | 63.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.0 (−7.8) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

34.0 (1.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

57.4 (14.1) |

61.9 (16.6) |

62.1 (16.7) |

55.6 (13.1) |

44.1 (6.7) |

34.0 (1.1) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

40.3 (4.6) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 162.7 | 163.1 | 212.5 | 225.6 | 256.6 | 257.3 | 268.2 | 268.2 | 219.3 | 211.2 | 151.0 | 139.0 | 2,534.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 54 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 59 | 63 | 59 | 61 | 51 | 48 | 57 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[49]. | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) |

41.7 (5.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

40.2 (4.5) |

45.1 (7.3) |

52.5 (11.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

72.1 (22.3) |

74.1 (23.4) |

70.1 (21.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

54.3 (12.4) |

47.2 (8.4) |

55.4 (13.0) |

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1656* | 1,000 | — |

| 1698* | 6,788 | +578.8% |

| 1711* | 10,538 | +55.2% |

| 1730* | 11,963 | +13.5% |

| 1731* | 8,628 | −27.9% |

| 1756* | 15,710 | +82.1% |

| 1773* | 21,876 | +39.2% |

| 1774* | 23,600 | +7.9% |

| 1782* | 29,363 | +24.4% |

| 1790 | 33,131 | +12.8% |

| 1800 | 60,489 | +82.6% |

| 1810 | 96,373 | +59.3% |

| 1820 | 123,706 | +28.4% |

| 1830 | 202,589 | +63.8% |

| 1840 | 312,710 | +54.4% |

| 1850 | 515,547 | +64.9% |

| 1860 | 813,669 | +57.8% |

| 1870 | 942,292 | +15.8% |

| 1880 | 1,164,674 | +23.6% |

| 1890 | 1,441,216 | +23.7% |

| 1900 | 1,850,093 | +28.4% |

| 1910 | 2,331,542 | +26.0% |

| 1920 | 2,284,103 | −2.0% |

| 1930 | 1,867,312 | −18.2% |

| 1940 | 1,889,924 | +1.2% |

| 1950 | 1,960,101 | +3.7% |

| 1960 | 1,698,281 | −13.4% |

| 1970 | 1,539,233 | −9.4% |

| 1980 | 1,428,285 | −7.2% |

| 1990 | 1,487,536 | +4.1% |

| 2000 | 1,537,195 | +3.3% |

| 2010 | 1,585,873 | +3.2% |

| 2013 | 1,626,159 | +2.5% |

| Sources:[50][51][52] | ||

| Racial composition | 2012[53] | 1990[54] | 1950[54] | 1900[54] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

White |

65.2% | 58.3% | 79.4% | 97.8% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 47.6% | 48.9% | n/a | n/a |

Black or African American |

18.4% | 22.0% | 19.6% | 2.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 25.8% | 26.0% | n/a | n/a |

Asian |

12.0% | 7.4% | 0.8% | 0.3% |

At the

According to 2012

The New York City Department of City Planning projects that Manhattan's population will increase by 289,000 people between 2000 and 2030, an increase of 18.8% over the period, second only to Staten Island, while the rest of the city is projected to grow by 12.7% over the same period. The school-age population is expected to grow 4.4% by 2030, in contrast to a small decline in the city as a whole. The elderly population is forecast to grow by 57.9%, with the borough adding 108,000 persons ages 65 and over, compared to 44.2% growth citywide.[59]

According to the 2009

In 2000, 56.4% of people living in Manhattan were

There were 738,644 households. 25.2% were married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 59.1% were non-families. 17.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them. 48% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was two and the average family size was 2.99.

Manhattan's population was spread out with 16.8% under the age of 18, 10.2% from 18 to 24, 38.3% from 25 to 44, 22.6% from 45 to 64, and 12.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.9 males.

Manhattan is one of the

The Manhattan ZIP Code 10021, on the Upper East Side is home to more than 100,000 people and has a per capita income of over $90,000.[64] It is one of the largest concentrations of extreme wealth in the United States. Most Manhattan neighborhoods are not as wealthy. The median income for a household in the county was $47,030, and the median income for a family was $50,229. Males had a median income of $51,856 versus $45,712 for females. The per capita income for the county was $42,922. About 17.6% of families and 20% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.8% of those under age 18 and 18.9% of those age 65 or over.[65]

Lower Manhattan (Manhattan south of

The borough is also experiencing a baby boom. Since 2000, the number of children under age five living in Manhattan grew by more than 32%.[67]

Religion

Manhattan is religiously diverse. The largest religious affiliation is the Roman Catholic Church, whose adherents constitute 564,505 persons (more than 36% of the population) and maintain 110 congregations.

Languages

As of 2010, 59.98% (902,267) of Manhattan residents, ages five and older, spoke only

Landmarks and architecture

The skyscraper, which has shaped Manhattan's distinctive skyline, has been closely associated with New York City's identity since the end of the 19th century. From 1890 to 1973, the

The

The former Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were located in Lower Manhattan. At 1,368 and 1,362 feet (417 and 415 m)*, the 110-story buildings were the world's tallest from 1972, until they were surpassed by the construction of the Willis Tower in 1974 (formerly known as the Sears tower located in Chicago).[81] One World Trade Center, a replacement for the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, is currently under construction and is slated to be ready for occupancy in 2013.[82]

In 1961, the

The

are all located on this densely populated island.The city is a leader in energy-efficient green office buildings, such as

While much of the park looks natural, it is almost entirely landscaped and contains several artificial lakes. The construction of Central Park in the 1850s was one of the era's most massive public works projects. Some 20,000 workers crafted the topography to create the English-style pastoral landscape Olmsted and Vaux sought to create. Workers moved nearly 3,000,000 cubic yards (2,300,000 m3)* of soil and planted more than 270,000 trees and shrubs.[88]

17.8% of the borough, a total of 2,686 acres (10.87 km2)*, are devoted to parkland. Almost 70% of Manhattan's space devoted to parks is located outside of Central Park, including 204 playgrounds, 251 Greenstreets, 371 basketball courts and many other amenities.[89]

The African Burial Ground National Monument at Duane Street preserves a site containing the remains of over 400 Africans buried during the 17th and 18th centuries. The remains were found in 1991 during the construction of the Foley Square Federal Office Building.

-

One World Trade Center is currently the tallest skyscraper in the Western Hemisphere.

-

The Chrysler Building was the tallest building in the city and the world from 1930–1931.

-

The Empire State Building was the world's tallest building from 1931 to 1972.

-

The twin towers of the former World Trade Center, New York's tallest buildings, 1972 to 2001.

-

Manhattan has served as home to theUnited Nations Headquarterssince 1952.

Cityscape

Economy

Manhattan has some of the nation's most valuable real estate, and has a reputation as one of the most expensive areas in the United States.[91] On September 20, 2012, The New York Times reported that "the income gap in Manhattan, already wider than almost anywhere else in the country, rivaled disparities in sub-Saharan Africa. ... The wealthiest fifth of Manhattanites made more than 40 times what the lowest fifth reported, a widening gap (it was 38 times, the year before) surpassed by only a few developing countries, including Namibia and Sierra Leone."[92]

Manhattan is the economic engine of New York City, with its 2.3 million workers in 2007 drawn from the entire New York metropolitan area accounting for almost two-thirds of all jobs in New York City.[93]

In 2010, Manhattan's daytime population was swelling to 3.94 million, with

Manhattan's most important economic sector lies in its role as the headquarters for the

Manhattan had approximately 520 million square feet (48.1 million m2) of office space in 2013,[97] making it the largest office market in the United States,[98] while Midtown Manhattan is the largest central business district in the nation.[99]

Lower Manhattan is the third largest central business district in the United States and is home to the

New York City is home to the most corporate headquarters of any city in the nation, the overwhelming majority based in Manhattan.

On December 19, 2011, then Mayor

The

As of 2013, the global

Manhattan's workforce is overwhelmingly focused on white collar professions, with manufacturing nearly extinct. Historically, the borough's corporate presence has been complemented by many independent retailers, though a recent influx of national chain stores has caused many to lament the creeping homogenization of Manhattan.[117]

Tourism is also vital to Manhattan's economy, and the landmarks of Manhattan are the focus of New York City's visitors, which was estimated to reach 55 million in 2014.[118] According to The Broadway League, shows on Broadway sold approximately US$1.27 billion worth of tickets in the 2013–2014 season, an increase of 11.4% from US$1.139 billion in the 2012–2013 season; attendance in 2013-2014 stood at 12.21 million, representing a 5.5% increase from the 2012–2013 season's 11.57 million.[119]

Media

Manhattan is served by the major New York City dailies, including

Television, radio and film

Modern New York City is familiar to many people around the globe thanks to its popularity as a setting for television series and films. Notable television shows set in Manhattan include I Love Lucy, Friends, Saturday Night Live, and Seinfeld.

The television industry developed in New York and is a significant employer in the city's economy. The four major American broadcast networks,

The oldest public-access television cable TV channel in the United States is the Manhattan Neighborhood Network, founded in 1971, offers eclectic local programming that ranges from a jazz hour to discussion of labor issues to foreign language and religious programming.[123] NY1, Time Warner Cable's local news channel, is known for its beat coverage of City Hall and state politics.

Education and scholarly activity

Education in Manhattan is provided by a vast number of public and private institutions. Public schools in the borough are operated by the New York City Department of Education, the largest public school system in the United States.[126] Charter schools include Success Academy Harlem 1 through 5, Success Academy Upper West, and Public Prep.

Some of the best-known New York City public high schools, such as

Many prestigious private prep schools are located in Manhattan, including the

As of 2003, 52.3% of Manhattan residents over age 25 have a bachelor's degree, the fifth highest of all counties in the country.[128] By 2005, about 60% of residents were college graduates and some 25% had earned advanced degrees, giving Manhattan one of the nation's densest concentrations of highly educated people.[129]

Manhattan has various colleges and universities including

The City University of New York (CUNY), the municipal college system of New York City, is the largest urban university system in the United States, serving more than 226,000 degree students and a roughly equal number of adult, continuing and professional education students.[130] A third of college graduates in New York City graduate from CUNY, with the institution enrolling about half of all college students in New York City. CUNY senior colleges located in Manhattan include: Baruch College, City College of New York, Hunter College, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and the CUNY Graduate Center (graduate studies and doctoral granting institution). The only CUNY community college located in Manhattan is the Borough of Manhattan Community College.

The

Manhattan is a world center for training and education in medicine and the life sciences.

Manhattan is served by the New York Public Library, which has the largest collection of any public library system in the country.[133] The five units of the Central Library—Mid-Manhattan Library, Donnell Library Center, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Andrew Heiskell Braille and Talking Book Library and the Science, Industry and Business Library—are all located in Manhattan.[134] More than 35 other branch libraries are located in the borough.[135]

Culture and contemporary life

Manhattan has been the scene of many important American cultural movements. In 1912, about 20,000 workers, a quarter of them women, marched upon

The Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s established the African-American literary canon in the United States. Manhattan's vibrant visual art scene in the 1950s and 1960s was a center of the American pop art movement, which gave birth to such giants as Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein. Perhaps no other artist is as associated with the downtown pop art movement of the late 1970s as Andy Warhol, who socialized at clubs like Serendipity 3 and Studio 54.

Broadway theatre is often considered the highest professional form of theatre in the United States. Plays and

Manhattan is also home to some of the most extensive art collections, both contemporary and historical, in the world including the

Manhattan is the borough most closely associated with New York City by non-residents; even some natives of New York City's boroughs outside Manhattan will describe a trip to Manhattan as "going to the city".[142]

The borough has a place in several American idioms. The phrase a New York minute is meant to convey a very short time, sometimes in hyperbolic form, as in "perhaps faster than you would believe is possible". It refers to the rapid pace of life in Manhattan.[143] The term "melting pot" was first popularly coined to describe the densely populated immigrant neighborhoods on the Lower East Side in Israel Zangwill's play The Melting Pot, which was an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet set by Zangwill in New York City in 1908.[144] The iconic Flatiron Building is said to have been the source of the phrase "23 skidoo" or scram, from what cops would shout at men who tried to get glimpses of women's dresses being blown up by the winds created by the triangular building.[145] The "Big Apple" dates back to the 1920s, when a reporter heard the term used by New Orleans stablehands to refer to New York City's racetracks and named his racing column "Around The Big Apple." Jazz musicians adopted the term to refer to the city as the world's jazz capital, and a 1970s ad campaign by the New York Convention and Visitors Bureau helped popularize the term.[146]

Sports

Manhattan is home to the NBA's New York Knicks, the NHL's New York Rangers, and the WNBA's New York Liberty, who all play their home games at Madison Square Garden, the only major professional sports arena in the borough. The New York Jets proposed a West Side Stadium for their home field, but the proposal was eventually defeated in June 2005, leaving them at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

Today, Manhattan is the only borough in New York City that does not have a professional baseball franchise. The Bronx has the Yankees (American League) and Queens has the Mets (National League) of Major League Baseball. The Minor League Baseball Brooklyn Cyclones play in Brooklyn, while the Staten Island Yankees play in Staten Island. Yet three of the four major league teams to play in New York City played in Manhattan. The New York Giants played in the various incarnations of the Polo Grounds at 155th Street and Eighth Avenue from their inception in 1883—except for 1889, when they split their time between Jersey City and Staten Island, and when they played in Hilltop Park in 1911—until they headed west with the Brooklyn Dodgers after the 1957 season.[147] The New York Yankees began their franchise as the Highlanders, named for Hilltop Park, where they played from their creation in 1903 until 1912. The team moved to the Polo Grounds with the 1913 season, where they were officially christened the New York Yankees, remaining there until they moved across the Harlem River in 1923 to Yankee Stadium.[148] The New York Mets played in the Polo Grounds in 1962 and 1963, their first two seasons, before Shea Stadium was completed in 1964.[149] After the Mets departed, the Polo Grounds was demolished in April 1964, replaced by public housing.[150][151]

The first national college-level basketball championship, the National Invitation Tournament, was held in New York in 1938 and remains in the city.[152] The New York Knicks started play in 1946 as one of the National Basketball Association's original teams, playing their first home games at the 69th Regiment Armory, before making Madison Square Garden their permanent home.[153] The New York Liberty of the WNBA have shared the Garden with the Knicks since their creation in 1997 as one of the league's original eight teams.[154] Rucker Park in Harlem is a playground court, famed for its streetball style of play, where many NBA athletes have played in the summer league.[155]

Though both of New York City's football teams play today across the Hudson River in MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey, both teams started out playing in the Polo Grounds. The New York Giants played side-by-side with their baseball namesakes from the time they entered the National Football League in 1925, until crossing over to Yankee Stadium in 1956.[156] The New York Jets, originally known as the Titans, started out in 1960 at the Polo Grounds, staying there for four seasons before joining the Mets in Queens in 1964.[157]

The New York Rangers of the National Hockey League have played in the various locations of Madison Square Garden since their founding in the 1926–1927 season. The Rangers were predated by the New York Americans, who started play in the Garden the previous season, lasting until the team folded after the 1941–1942 NHL season, a season it played in the Garden as the Brooklyn Americans.[158]

The

Government

Since New York City's consolidation in 1898, Manhattan has been governed by the New York City Charter, which has provided for a strong

The office of

Since 1990, the largely powerless Borough President has acted as an advocate for the borough at the mayoral agencies, the City Council, the New York state government, and corporations. Manhattan's current

| Year | Democrats | Republicans |

|---|---|---|

2012

|

83.7% 500,159 | 14.9% 89,119 |

2008

|

85.7% 572,126 | 13.5% 89,906 |

2004

|

82.1% 526,765 | 16.7% 107,405 |

2000

|

79.8% 449,300 | 14.2% 79,921 |

1996

|

80.0% 394,131 | 13.8% 67,839 |

1992

|

78.2% 416,142 | 15.9% 84,501 |

1988

|

76.1% 385,675 | 22.9% 115,927 |

1984

|

72.1% 379,521 | 27.4% 144,281 |

1980

|

62.4% 275,742 | 26.2% 115,911 |

1976

|

73.2% 337,438 | 25.5% 117,702 |

1972

|

66.2% 354,326 | 33.4% 178,515 |

1968

|

70.0% 370,806 | 25.6% 135,458 |

1964

|

80.5% 503,848 | 19.2% 120,125 |

1960

|

65.3% 414,902 | 34.2% 217,271 |

1956

|

55.74% 377,856 | 44.26% 300,004 |

1952

|

58.47% 446,727 | 39.30% 300,284 |

1948

|

52.20% 380,310 | 33.18% 241,752 |

Politics

The Democratic Party holds most public offices. Registered Republicans are a minority in the borough, only constituting approximately 12% of the electorate. Registered Republicans are more than 20% of the electorate only in the neighborhoods of the Upper East Side and the Financial District. The Democrats hold 66.1% of those registered in a party. 21.9% of the voters were unaffiliated (independents).[169]

Manhattan is divided between four congressional districts, all of which are represented by Democrats.

- Spanish Harlem, Washington Heights, Inwoodand parts of the Upper West Side.

- Jerrold Nadler represents the 8th district, based on the West Side, which covers most of the Upper West Side, Hell's Kitchen, Chelsea, Greenwich Village, Chinatown, Tribeca and Battery Park City, as well as some sections of Southwest Brooklyn.

- Teddy Roosevelt and John Lindsay. It covers most of the Upper East Side, Yorkville, Gramercy Park, Roosevelt Island and most of the Lower East Side and the East Village, as well as portions of western Queens.

- Nydia Velázquez of the Brooklyn/Queens-based 12th district, represents a few heavily Puerto Rican sections of the Lower East Side, including Avenues C and D of Alphabet City.

No

Federal offices

The

Both the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit are located in lower Manhattan's Foley Square, and the U.S. Attorney and other federal offices and agencies maintain locations in that area.

Crime and public safety

Starting in the mid-19th century, the United States became a magnet for immigrants seeking to escape poverty in their home countries. After arriving in New York, many new arrivals ended up living in squalor in the slums of the Five Points neighborhood, an area between Broadway and the Bowery, northeast of New York City Hall. By the 1820s, the area was home to many gambling dens and brothels, and was known as a dangerous place to go. In 1842, Charles Dickens visited the area and was appalled at the horrendous living conditions he had seen.[177] The area was so notorious that it even caught the attention of Abraham Lincoln, who visited the area before his Cooper Union speech in 1860.[178] The predominantly Irish Five Points Gang was one of the country's first major organized crime entities.

As Italian immigration grew in the early 20th century many joined ethnic gangs, including

New York City experienced a sharp increase in crime during the 1960s and 1970s, with a near fivefold jump in the total number of police-recorded crimes, from 21.09 per thousand in 1960 to a peak of 102.66 in 1981. Homicides continued to increase in the city for another decade, with murders recorded by the

Based on 2005 data, New York City has the lowest crime rate among the ten largest cities in the United States.

Since 1990, crime in Manhattan has plummeted in all categories tracked by the CompStat profile. A borough that saw 503 murders in 1990 has seen a drop of nearly 88% to 62 in 2008. Robbery and burglary are down by more than 80% during the period, and auto theft has been reduced by more than 93%. In the seven major crime categories tracked by the system, overall crime has declined by more than 75% since 1990, and year-to-date statistics through May 2009 show continuing declines.[185]

Housing

In the early days of Manhattan, wood construction and poor access to water supplies left the city vulnerable to fires. In 1776, shortly after the Continental Army evacuated Manhattan and left it to the British, a massive fire broke out destroying one-third of the city and some 500 houses.[186]

The rise of immigration near the turn of the 20th century left major portions of Manhattan, especially the

Manhattan offers a wide array of public and private housing options. There were 798,144 housing units in Manhattan as of the 2000 Census, at an average density of 34,756.7 per square mile (13,421.8/km2).[8] Only 20.3% of Manhattan residents lived in owner-occupied housing, the second-lowest rate of all counties in the nation, behind The Bronx.[58] Although the city of New York has the highest average cost for rent in the United States, it simultaneously hosts a higher average of income per capita. Because of this, rent is a lower percentage of annual income than in several other American cities.[189]

As of 2012[update], Manhattan's real estate market for luxury housing was among the most expensive in the world.[190]

Infrastructure

Streets

Manhattan has fixed

The

According to the original Commissioner's Plan there were

Fifteen crosstown streets were designated as 100 feet (30 m) wide, including

A consequence of the strict grid plan of most of Manhattan, and the grid's skew of approximately 28.9 degrees, is a phenomenon sometimes referred to as Manhattanhenge (by analogy with Stonehenge).[194] On separate occasions in late May and early July, the sunset is aligned with the street grid lines, with the result that the sun is visible at or near the western horizon from street level.[194][195] A similar phenomenon occurs with the sunrise in January and December.

The Wildlife Conservation Society, which operates the zoos and aquariums in the city, is currently undertaking The Mannahatta Project, a cartoon simulation to visually reconstruct the ecology and geography of Manhattan when Henry Hudson first sailed by in 1609, and compare it to what we know of the island today.[196]

Transportation

Manhattan is unique in the U.S. for intense use of public transport and lack of private car ownership. While 88% of Americans nationwide drive to their jobs and only 5% use public transport, mass transit is the dominant form of travel for residents of Manhattan, with 72% of borough residents using public transport and only 18% driving to work.[197][198] According to the United States Census, 2000, more than 77.5% of Manhattan households do not own a car.[199]

In 2008, Mayor Bloomberg

The

The metro region's commuter rail lines converge at

Being primarily an island, Manhattan is linked to New York City's outer boroughs by numerous

Manhattan Island is linked to New York City's outer boroughs and New Jersey by several

The

Manhattan has three public heliports. US Helicopter offered regularly scheduled helicopter service connecting the Downtown Manhattan Heliport with John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens and Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey before going out of business in 2009.[221]

New York City has the largest clean-air diesel-hybrid and compressed natural gas bus fleet, which also operates in Manhattan, in the country. It also has some of the first hybrid taxis, most of which operate in Manhattan.[222]

Crosstown traffic refers primarily to vehicular traffic between

Utilities

Gas and electric service is provided by

Manhattan, surrounded by two

Manhattan witnessed the doubling of the

The New York City Department of Sanitation is responsible for garbage removal.[229] The bulk of the city's trash ultimately is disposed at mega-dumps in Pennsylvania, Virginia, South Carolina and Ohio (via transfer stations in New Jersey, Brooklyn and Queens) since the 2001 closure of the Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island.[230] A small amount of trash processed at transfer sites in New Jersey is sometimes incinerated at waste-to-energy facilities. Like New York City, New Jersey and much of Greater New York relies on exporting its trash to far-flung areas.

References

- ^ Edelman, Susan (January 6, 2008). "Charting post-9/11 deaths". Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- ^ Katia Hetter (November 12, 2013). "It's official: One World Trade Center to be tallest U.S. skyscraper". CNN. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ Mary Johnson (October 29, 2012). "VIDEO: Dramatic Explosion at East Village Con Ed Plant". Copyright © 2009–2012, DNAinfo.com. All Rights Reserved. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ "OccupyWallStreet - About". The Occupy Solidarity Network, Inc. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Robert S. Eshelman (November 15, 2012). "ADAPTATION: Political support for a sea wall in New York Harbor begins to form". © 1996–2012 E&E Publishing, LLC. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ New York City Administrative Code Section 2-202 Division into boroughs and boundaries thereof – Division Into Boroughs And Boundaries Thereof.[dead link], Lawyer Research Center. Accessed May 16, 2007. "The borough of Manhattan shall consist of the territory known as New York county, which shall contain all that part of the city and state, including that portion of land commonly known as Marble Hill and included within the county of New York and borough of Manhattan for all purposes pursuant to chapter nine hundred thirty-nine of the laws of nineteen hundred eighty-four and further including the islands called Manhattan Island, Governor's Island, Bedloe's Island, Ellis Island, Franklin D. Roosevelt Island, Randall's Island and Oyster Island..."

- ^ wide (at its widest point)."

- ^ a b c New York—Place and County Subdivision[dead link], United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes: Spuyten Duyvil Swing Bridge; Restoring a Link In the City's Lifeline". The New York Times, March 6, 1988. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ Jackson, Nancy Beth. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Marble Hill; Tiny Slice of Manhattan on the Mainland". The New York Times, January 26, 2003. Accessed June 30, 2009. "The building of the Harlem River Ship Canal turned the hill into an island in 1895, but when Spuyten Duyvel Creek on the west was filled in before World War I, the 51 acres (21 ha)* became firmly attached to the mainland and the Bronx."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mannahattawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ISBN 978-0-8232-1245-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7838-9785-1.

- ^ Iglauer, Edith (November 4, 1972). "The Biggest Foundation". The New Yorker.

- ^ ASLA 2003 The Landmark Award, American Society of Landscape Architects. Accessed May 17, 2007.

- ^ "Manhattan Schist in Bennett Park". BennyLabamba.com. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ John H. Betts The Minerals of New York City originally published in Rocks & Minerals magazine, Volume 84, No. 3 pages 204–252 (2009).

- ^ Samuels, Andrea. "An Examination of Mica Schist by Andrea Samuels, Micscape magazine. Photographs of Manhattan schist". Microscopy-uk.org.uk. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Manhattan Schist in New York City Parks – J. Hood Wright Park". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Why is Manhattan skyline missing tall buildings in the middle?". Yahoo. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Quinn, Helen (June 6, 2013). "How ancient collision shaped New York skyline". BBC Science. BBC.co.uk. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

These rocks are Manhattan schist, part of that ancient supercontinent, fragments of Pangaea left behind when the continent split. They are just glimpses of what is below the surface in abundance in Downtown and Midtown. And it is these fragments of very hard rock that provide the perfect foundations for New York's highest buildings. Where Manhattan schist can be found very close to the surface you can build high, and so Downtown and Midtown have become home to Manhattan's tallest buildings.

- ^ Barr, Jason; Tassier, Troy & Trendafilov, Rossen (October 2010). "Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890–1915" (PDF). Fordham University. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ Chaban, Matt (January 17, 2012). "Uncanny Valley: The Real Reason There Are No Skyscrapers in the Middle of Manhattan". The New York Observer. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Chaban, Matt (January 25, 2012). "Paul Goldberger and Skyscraper Economist Jason Barr Debate the Manhattan Skyline" (PDF). The New York Observer. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Jessica Robertson and Mark Petersen (July 17, 2014). "New Insight on the Nation's Earthquake Hazards". United States Geologic Survey. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Senft, Bret. "If You're Thinking of Living In/TriBeCa; Families Are the Catalyst for Change", The New York Times, September 26, 1993. Accessed June 30, 2009. "Families have overtaken commerce as the catalyst for change in this TRIangle BElow CAnal Street (although the only triangle here is its heart: Hudson Street meeting West Broadway at Chambers Street, with Canal its north side) ... Artists began seeking refuge from fashionable SoHo (SOuth of HOuston) as early as the mid-70s."

- ^ Cohen, Joyce. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Nolita; A Slice of Little Italy Moving Upscale", The New York Times, May 17, 1998. Accessed June 30, 2009. "NO ONE is quite certain what to call this part of town. Nolita—north of Little Italy, that is—certainly pinpoints it geographically. The not-quite-acronym was apparently coined several years ago by real-estate brokers seeking to give the area at least a little cachet."

- ^ Louie, Elaine. "The Trendy Discover NoMad Land, and Move In"

- ^ Feirstein, Sanna. (2001), Naming New York: Manhattan Places and How They Got Their Names: New York: New York University Press, p. 103

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam. "Soho. Nolita. Dumbo. NoMad? Branding the last unnamed neighborhood in Manhattan. Published April 11, 2010"

- ^ Pitts, David. U.S. Postage Stamp Honors Harlem's Langston Hughes at the Wayback Machine (archived October 1, 2006), United States Department of State. Accessed June 30, 2009. "Harlem, or Nieuw Haarlem, as it was originally named, was established by the Dutch in 1658 after they took control from Native Americans. They named it after Haarlem, a city in the Netherlands."

- ^ Bruni, Frank. "The Grounds He Stamped: The New York Of Ginsberg", The New York Times, April 7, 1997. Accessed June 30, 2009. "Indeed, for all the worldwide attention that Mr. Ginsberg received, he was always a creature and icon principally of downtown Manhattan, his world view forged in its crucible of political and sexual passions, his eccentricities nurtured by those of its peculiar demimonde, his individual myth entwined with that of the bohemian East Village in which he made his home. He embodied the East Village and the Lower East Side, Bill Morgan, a friend and Mr. Ginsberg's archivist, said yesterday."

- ^ Dunlap, David W. "The New Chelsea's Many Faces", The New York Times, November 13, 1994. Accessed June 30, 2009. "Gay Chelsea's role has solidified with the arrival of A Different Light bookstore, a cultural cornerstone that had been housed for a decade in an 800-square-foot (74 m2) nook at 548 Hudson Street, near Perry Street. It now takes up more than 5,000 square feet (500 m2)* at 151 West 19th Street and its migration seems to embody a northward shift of gay life from Greenwich Village... Because of Chelsea's reputation, Mr. Garmendia said, single women were not likely to move in. But single men did. "The whole neighborhood became gay during the 70's", he said."

- ^ Grimes, Christopher. "WORLD NEWS: New York's Chinatown starts to feel the pinch over 'the bug'"[dead link], Financial Times, April 14, 2003. Accessed May 19, 2007. "New York's Chinatown is the site of the largest concentration of Chinese people in the western hemisphere."

- ^ Chinatown: A World of Dining, Shopping, and History at the Wayback Machine (archived July 9, 2006), NYC & Company, accessed June 30, 2009. "No visit to New York City is complete without exploring the sights, cuisines, history, and shops of the biggest Chinatown in the United States. The largest concentration of Chinese people—150,000—in the Western Hemisphere are in a two-square-mile area in downtown Manhattan that's loosely bounded by Lafayette, Worth, and Grand streets and East Broadway."

- ^ Kris Ensminger (October 10, 2008). "Good Eating Curry Hill More Than Tandoori". The New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ^ Petzold, Charles. " How Far from True North are the Avenues of Manhattan?", accessed April 30, 2007. "However, the orientation of the city's avenues was fixed to be parallel with the axis of Manhattan Island and has only a casual relationship to true north and south. Maps that are oriented to true north (like the one at the right) show the island at a significant tilt. In truth, avenues run closer to northeast and southwest than north and south."

- ^ a b NYC Basics at the Wayback Machine (archived October 11, 2007), NYC & Company, accessed June 30, 2009. "Downtown (below 14th Street) contains Greenwich Village, SoHo, TriBeCa, and the Wall Street financial district."

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. "World Map of Köppen-Geiger climate classification". The University of Melbourne. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "New York Polonia Polish Portal in New York". NewYorkPolonia.com. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ "New York, NY". NOAA. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ "The Climate of New York". New York State Climate Office. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Riley, Mary Elizabeth (2006). "Assessing the Impact of Interannual Climate Variability on New York City's Reservoir System" (PDF). Cornell University Graduate School for Atmospheric Science. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ "Keeping New York City Cool Is The Job Of NASA's Heat Seekers."[dead link], Spacedaily.com, February 9, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2007. "The urban heat island occurrence is particularly pronounced during summer heat waves and at night when wind speeds are low and sea breezes are light. During these times, New York City's air temperatures can rise 7.2 °F (4.0 °C) higher than in surrounding areas."

- ^ Belvedere Castle at NYC Parks

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "New York Central Park, NY Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "New York, New York, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "New York County (Manhattan Borough), New York State & County QuickFacts". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "Census" (PDF). United States Census. page 36

- ^ Campbell Gibson. "Population of the 100 largest cities and other urban places in the United States: 1790 to 1990". United States Bureau of the Census.

- ^ a b "State and County QuickFacts: New York County (Manhattan Borough), New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c "New York - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ "State and County QuickFacts: New York County (Manhattan Borough), New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "State and County QuickFacts: New York (city), New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "Population Density", Geographic Information Systems – GIS of Interest. Accessed June 30, 2009. "What I discovered is that out of the 3140 counties listed in the Census population data only 178 counties were calculated to have a population density over one person per acre. Not surprisingly, New York County (which contains Manhattan) had the highest population density with a calculated 104.218 persons per acre."

- ^ a b Percent of Occupied Housing Units That are Owner-occupied[dead link], United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ New York City Population Projections by Age/Sex & Borough 2000–2030, New York City Department of City Planning, December 2006. Accessed May 18, 2007.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "New York County, New York – ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2009". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved July 24, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "New York County, New York – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2009". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved May 7, 2012.[dead link]

- CNN Money. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ Newman, Jeffrey L. "Comprehensive revision of local area personal income: preliminary estimates for 2002 and revised estimates for 1969–2001", Survey of Current Business, June 2004. Accessed May 29, 2007. "Per capita personal income in New York County (Manhattan), New York, at ,4,591, or 274 percent of the national average, was the highest."

- ^ Zip Code Tabulation Area 10021[dead link], United States Census 2000. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ York County, New York[dead link], United States Census 2000. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer. "Baby Strollers and Supermarkets Push Into the Financial District", The New York Times, April 15, 2005. Accessed May 11, 2007.

- ^ Roberts, Sam. "In Surge in Manhattan Toddlers, Rich White Families Lead Way", The New York Times, March 27, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ New York County, New York, Association of Religion Data Archives. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- ^ "MLA Language Map Data Center". Modern Language Association. Retrieved December 20, 2013. Enter New York County, New York, 2010 in data entry.

- ^ McKinley, Jesse. "F.Y.I.: Tall, Taller. Tallest", The New York Times, November 5, 1995. p. CY2. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ "Big Span Project Initiated by City; Manhattan Plaza of Brooklyn Bridge Would Be Rebuilt to Cope With Traffic Increase COST IS PUT AT $6,910,000 Demolition Program is Set – Street System in the Area Also Faces Rearranging", The New York Times, July 24, 1954. p. 15.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes/The Park Row Building, 15 Park Row; An 1899 'Monster' That Reigned High Over the City", The New York Times, March 12, 2000. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. " Streetscapes/Singer Building; Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost", The New York Times, January 2, 2005. Accessed May 15, 2007. "The 41-story Singer Building, the tallest in the world in 1908 when it was completed at Broadway and Liberty Street, was until September 11, 2001, the tallest structure ever to be demolished. The building, an elegant Beaux-Arts tower, was one of the most painful losses of the early preservation movement when it was razed in 1967.... Begun in 1906, the Singer Building incorporated Flagg's model for a city of towers, with the 1896 structure reconstructed as the base, and a 65-foot-square shaft rising 612 feet (187 m)* high, culminating in a bulbous mansard and giant lantern at the peak."

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes/Metropolitan Life at 1 Madison Avenue; For a Brief Moment, the Tallest Building in the World", The New York Times, May 26, 1996. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. "Condos to Top Vaunted Tower Of Woolworth", The New York Times, November 2, 2000. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ "Denies Altering Plans for Tallest Building; Starrett Says Height of Bank of Manhattan Structure Was Not Increased to Beat Chrysler.", The New York Times, October 20, 1929. p. 14.

- ^ "Bank of Manhattan Built in Record Time; Structure 927 feet (283 m)* High, Second Tallest in World, Is Erected in Year of Work.", The New York Times, May 6, 1930. p. 53.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes: The Chrysler Building; Skyscraper's Place in the Sun", The New York Times, December 17, 1995. Accessed June 30, 2009. "Then Chrysler and Van Alen again revised the design, this time in order to win a height competition with the 921-foot (281 m) tower then rising at 40 Wall Street. This was done in secret, using as a staging area the huge square fire-tower shaft, intended to vent smoke from the stairways. Inside the shaft, Van Alen had teams of workers assemble the framework for a 185-foot-high spire that, when lifted into place in the fall of 1929, made the Chrysler building, at 1046 feet, 4.75 inches high, the tallest in the world."

- ^ "Rivalry for Height is Seen as Ended; Empire State's Record to Stand for Many Years, Builders and Realty Men Say. Practical Limit Reached; Its Top Rises 1,250 feet (380 m)*, but Staff Carrying Instruments Extends Pinnacle to 1265.5 Feet.", The New York Times, May 2, 1931. p. 7.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes: The Empire State Building; A Red Reprise for a '31 Wonder", The New York Times, June 14, 1992. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ Barss, Karen. "The History of Skyscrapers: A race to the top", Information Please. Accessed May 17, 2007. "The Empire State Building would reign supreme among skyscrapers for 41 years until 1972, when it was surpassed by the World Trade Center (1,368 feet, 110 stories). Two years later, New York City lost the distinction of housing the tallest building when the Willis Tower was constructed in Chicago (1450 feet, 110 stories)."

- ^ "About the WTC". Silverstein Properties. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes/'The Destruction of Penn Station'; A 1960s Protest That Tried to Save a Piece of the Past", The New York Times, May 20, 2001. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ About the Landmarks Preservation Commission[dead link], New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Accessed May 17, 2007.

- ^ "Requiem For Penn Station", CBS News, October 13, 2002. Accessed May 17, 2007.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin. "7 World Trade Center and Hearst Building: New York's Test Cases for Environmentally Aware Office Towers", The New York Times, April 16, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ Central Park General Information, Central Park Conservancy. Retrieved September 21, 2006.

- ^ Central Park History, Central Park Conservancy. Retrieved September 21, 2006.

- ^ Environment at the Wayback Machine (archived April 11, 2007), Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ a b "2013 WFE Market Highlights" (PDF). World Federation of Exchanges. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ The most expensive ZIP codes in America, Forbes, September 26, 2003. Accessed June 29, 2009.

- ^ Tim Phillips, "The Occupy Movement is a Response to Social Stratification; it's not 'Economic Terrorism'", Activist Defense, September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Manhattan Average Weekly Wage in Manhattan at $2,821 in First Quarter 2007" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor. November 19, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ "The Dynamic Population of Manhattan" (PDF). Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "Commuting shifts in top 10 metro areas", USA Today, May 20, 2005. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ Thomas P. DiNapoli (New York State Comptroller) and Kenneth B. Bleiwas (New York State Deputy Comptroller) (October 2013). "The Securities Industry in New York City" (PDF). Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "What is an office condominium?". Rudder Property Group. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ "Understanding The Manhattan Office Space Market". Officespaceseeker.com. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "Marketbeat United States CBD Office Report 2Q11" (PDF). Cushman & Wakefield, Inc. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Ambereen Choudhury, Elisa Martinuzzi & Ben Moshinsky (November 26, 2012). "London Bankers Bracing for Leaner Bonuses Than New York". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Sanat Vallikappen (November 10, 2013). "Pay Raises for Bank Risk Officers in Asia Trump New York". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Fortune Magazine: New York State and City Home to Most Fortune 500 Companies, Empire State Development Corporation, press release dated April 8, 2005, accessed April 26, 2007. "New York City is also still home to more Fortune 500 headquarters than any other city in the country."

- ^ "What is an office condominium?". Rudder Property Group. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ "Understanding The Manhattan Office Space Market". Officespaceseeker.com. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ "Marketbeat United States CBD Office Report 2Q11" (PDF). Cushman & Wakefield, Inc. Retrieved October 18, 2013.[dead link]

- ^ Lower Manhattan Recovery Office, Federal Transit Administration, accessed June 23, 2014. "Lower Manhattan is the third largest business district in the nation. Prior to September 11th more than 385,000 people were employed there and 85% of those employees used public transportation to commute to work."

- ^ David Enrich, Jacob Bunge, and Cassell Bryan-Low (July 9, 2013). "NYSE Euronext to Take Over Libor". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Megan Rose Dickey and Jillian D'Onfro (October 24, 2013). "SA 100 2013: The Coolest People In New York Tech". Business Insider. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "Industry Stats By Date". National Venture Capital Association. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ Morris, Keiko (April 29, 2014). "Widening Tech 'Alley' Outgrows Its Name: Label Is Giving Way to References to Submarkets like Chelsea, Flatiron/Madison Square". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "Telecommunications and Economic Development in New York City: A Plan for Action" (PDF). New York City Economic Development Corporation. March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 4, 2006 suggested (help) - ^ Ivan Pereira (December 10, 2013). "City opens nation's largest continuous Wi-Fi zone in Harlem". amNewYork/Newsday. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Jon Brodkin (June 9, 2014). "Verizon will miss deadline to wire all of New York City with FiOS". Condé Nast. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA (December 19, 2011). "Cornell Alumnus Is Behind $350 Million Gift to Build Science School in City". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Ju, Anne (December 19, 2011). "'Game-changing' Tech Campus Goes to Cornell, Technion". Cornell University. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Morris, Keiko (July 28, 2014). "Wanted: Biotech Startups in New York City: The Alexandria Center for Life Science Looks to Expand". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ Stasi, Linda. NY, OH: It's Cleaner, Whiter, Brighter, The Village Voice, September 24, 1997. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ Michael Howard Saul (December 10, 2013). "New York City Sees Record High Tourism in 2013". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ "Broadway Calendar-Year Statistics". The Broadway League. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ New York City Newspapers and News Media, ABYZ News Links. Accessed May 1, 2007.

- Google Book Search, p. 113. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ President's Bio[dead link], WNYC, accessed May 1, 2007. "Heard by over 1.2 million listeners each week, WNYC radio is the largest public radio station in the country and is dedicated to producing broadcasting that extends New York City's cultural riches to public radio stations nationwide."

- ^ Community Celebrates Public Access TV's 35th Anniversary[dead link], Manhattan Neighborhood Network press release dated August 6, 2006, accessed April 28, 2007. "Public access TV was created in the 1970s to allow ordinary members of the public to make and air their own TV shows—and thereby exercise their free speech. It was first launched in the U.S. in Manhattan July 1, 1971, on the Teleprompter and Sterling Cable systems, now Time Warner Cable."

- ^ Wienerbronner, Danielle (2010-11-09). "Most Beautiful College Libraries". TheHuffingtonPost.com. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- Daily News. Archived from the originalon January 2, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ^ New York: Education and Research, City Data. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- ^ La Scoula d'Italia[dead link], accessed June 29, 2009.

- ^ Percent of People 25 Years and Over Who Have Completed a Bachelor's Degree[dead link], United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick. "New York Area Is a Magnet For Graduates", The New York Times, August 16, 2006. Accessed March 27, 2008. "In Manhattan, nearly three out of five residents were college graduates and one out of four had advanced degrees, forming one of the highest concentrations of highly educated people in any American city."

- ^ The City University of New York is the nation's largest urban public university, City University of New York, accessed June 30, 2009. "The City University of New York is the nation's largest urban public university..."

- ^ New York City Economic Development Corporation (November 18, 2004). "Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and Economic Development Corporation President Andrew M. Alper Unveil Plans to Develop Commercial Bioscience Center in Manhattan". Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ National Institutes of Health (2003). "NIH Domestic Institutions Awards Ranked by City, Fiscal Year 2003". Archived from the original on June 26, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ "Nation's Largest Libraries". LibrarySpot. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ The Central Libraries[dead link], New York Public Library. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Manhattan Map, New York Public Library. Retrieved June 6, 2006.

- Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Weber, Bruce. "Critic's Notebook: Theater's Promise? Look Off Broadway", The New York Times, July 2, 2003. Accessed May 29, 2007. "It's also true that what constitutes Broadway is easy to delineate; it's a universe of 39 specified theaters, which all have at least 500 seats. Off Broadway is generally considered to comprise theaters from 99 to 499 seats (anything less is thought of as Off Off), which ostensibly determines the union contracts for actors, directors and press agents."

- ^ Theatre 101, Theatre Development Fund. Accessed May 29, 2007.

- ABC Classic FM. Accessed June 19, 2007. "James Levine made his Metropolitan Opera debut at the age of 27, conducting Tosca.... Since the mid eighties he has held the role of Artistic Director, and it is under his tenure that the Met has become the most prestigious opera house in the world."

- ^ "Stylish Traveler: Chelsea Girls", Travel + Leisure, September 2005. Accessed May 14, 2007. "With more than 200 galleries, Chelsea has plenty of variety."

- ^ "City Planning Begins Public Review for West Chelsea Rezoning to Permit Housing Development and Create Mechanism for Preserving and Creating Access to the High Line", New York City Department of City Planning press release dated December 20, 2004. Accessed May 29, 2007. "Some 200 galleries have opened their doors in recent years, making West Chelsea a destination for art lovers from around the City and the world."

- ^ Purdum, Todd S. "Political memo; An Embattled City Hall Moves to Brooklyn", The New York Times, February 22, 1992. Accessed June 30, 2009. ""Leaders in all of them fear that recent changes in the City Charter that shifted power from the borough presidents to the City Council have diminished government's recognition of the sense of identity that leads people to say they live in the Bronx, and to describe visiting Manhattan as 'going to the city.'"

- ^ "New York Minute". Dictionary of American Regional English. January 1, 1984. Retrieved September 5, 2006.

- Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Dolkart, Andrew S. "The Architecture and Development of New York City: The Birth of the Skyscraper – Romantic Symbols", Columbia University, accessed May 15, 2007. "It is at a triangular site where Broadway and Fifth Avenue—the two most important streets of New York—meet at Madison Square, and because of the juxtaposition of the streets and the park across the street, there was a wind-tunnel effect here. In the early twentieth century, men would hang out on the corner here on Twenty-third Street and watch the wind blowing women's dresses up so that they could catch a little bit of ankle. This entered into popular culture and there are hundreds of postcards and illustrations of women with their dresses blowing up in front of the Flatiron Building. And it supposedly is where the slang expression "23 skidoo" comes from because the police would come and give the voyeurs the 23 skidoo to tell them to get out of the area."

- ^ "Mayor Giuliani signs legislation creating "Big Apple Corner" in Manhattan", New York City press release dated February 12, 1997.

- ^ Giants Ballparks: 1883 – present, MLB.com. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ Yankee Ballparks: 1903 – present, MLB.com. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ Mets Ballparks: 1962 – present, MLB.com. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ Drebinger, John. "The Polo Grounds, 1889–1964: A Lifetime of Memories; Ball Park in Harlem Was Scene of Many Sports Thrills", The New York Times, January 5, 1964. p. S3.

- ^ Arnold, Martin. "Ah, Polo Grounds, The Game is Over; Wreckers Begin Demolition for Housing Project", The New York Times, April 11, 1964. p. 27.

- ^ History of the National Invitation Tournament, National Invitation Tournament. Accessed May 8, 2007. "Tradition. The NIT is steeped in it. The nation's oldest postseason collegiate basketball tournament was founded in 1938."

- NBA.com. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ The New York Liberty Story, Women's National Basketball Association. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ Rucker Park, ThinkQuest New York City. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- ^ The Giants Stadiums: Where the Giants have called home from their inception in 1925 to the present[dead link], New York Giants, dated November 7, 2002. Accessed May 8, 2007. "The Giants shared the Polo Grounds with the New York Baseball Giants from the time they entered the league in 1925 until they moved to the larger Yankee Stadium for the start of the 1956 season."

- ^ Stadiums of The NFL: Shea Stadium, Stadiums of the NFL. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ New York Americans, Sports Encyclopedia. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- ^ "A ,.5 Million Gamble", Time (magazine), June 30, 1975. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- ^ Collins, Glenn. "Built for Speed, And Local Pride; Track Stadium Emerges On Randalls Island", The New York Times, August 20, 2004. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ "Mayor Michael Bloomberk, Parks & Recreation Commissioner Adrian Benepe and the Randall's Island Sports Foundation Name New York City's Newest Athletic Facility Icahn Stadium", Mayor of New York City press release, dated January 28, 2004. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- Association of the Bar of the City of New York. Accessed May 11, 2007. "Unlike most cities that employ nonpartisan election systems, New York City has a very strong mayor system and, following the 1989 Charter Amendments, an increasingly powerful City Council."

- ^ Cornell Law School Supreme Court Collection: Board of Estimate of City of New York v. Morris, Cornell Law School. Retrieved June 12, 2006.

- ^ [1], New York Times. Accessed January 25, 2014. "New York 2013 Election Results."

- ^ Biography of Cyrus R. Vance[dead link], New York County District Attorney's Office. Accessed April 27, 2007. "He returned to private life until 1974, when he made the first of eight successful bids for election as District Attorney of New York County."

- ^ Society of Foreign Consuls: About us. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ Manhattan Municipal Building[dead link], New York City. Accessed June 29, 2009.

- ^ "Election results from the N.Y. Times". Elections.nytimes.com. December 9, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- ^ Grogan, Jennifer. Election 2004—Rise in Registration Promises Record Turnout, Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, accessed April 25, 2007. "According to the board's statistics for the total number of registered voters as of the October 22 deadline, there were 1.1 million registered voters in Manhattan, of which 727,071 were Democrats and 132,294 were Republicans, which is a 26.7 percent increase from the 2000 election, when there were 876,120 registered voters."

- ^ President—History: New York County, Our Campaigns. Accessed May 1, 2007.

- ^ 2004 General Election: Statement and Return of the Votes for the Office of President and Vice President of the United States[dead link] (PDF), New York City Board of Elections, dated December 1, 2004. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ National Overview: Top Zip Codes 2004 – Top Contributing Zip Codes for All Candidates (Individual Federal Contributions ( 00+)), The Color of Money. Accessed May 29, 2007.

- ^ Big Donors Still Rule The Roost, Public Campaign, press release dated October 29, 2004. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ "Post Office Location – James A. Farley." United States Postal Service. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ New York City's main post office stops 24-hour service, Associated Press, Friday, April 17, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ "Zip code lookup".

- ^ Christiano, Gregory. "The Five Points", Urbanography. Accessed May 16, 2007.

- ^ Walsh, John, "The Five Points"[dead link], Irish Cultural Society of the Garden City Area, September 1994. Accessed May 16, 2007. "The Five Points slum was so notorious that it attracted the attention of candidate Abraham Lincoln who visited the area before his Cooper Union Address."

- ^ Al Capone, Chicago History Museum. Accessed May 16, 2007. "Capone was born on January 17, 1899, in Brooklyn, New York.... He became part of the notorious Five Points gang in Manhattan and worked in gangster Frankie Yale's Brooklyn dive, the Harvard Inn, as a bouncer and bartender."

- ^ a b Jaffe, Eric. "Talking to the Feds: The chief of the FBI's organized crime unit on the history of La Cosa Nostra" at the Wayback Machine (archived June 15, 2007), Smithsonian (magazine), April 2007. Accessed May 16, 2007.

- ^ Langan, Patrick A. and Durose, Matthew R. "The Remarkable Drop in Crime in New York City" (PDF). United States Department of Justice, October 21, 2004. Accessed June 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Zeranski, Todd. NYC Is Safest City as Crime Rises in U.S., FBI Say". Bloomberg News, June 12, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2007.

- ^ 13th Annual Safest (and Most Dangerous) Cities: Top and Bottom 25 Cities Overall[dead link], accessed May 16, 2007.

- City Journal (New York), Summer 2006. Accessed May 16, 2007. "But to his immense credit (and that of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has backed him), Kelly has maintained the heart of New York's policing revolution—the now-famous accountability mechanism known as Compstat, a weekly crime-control meeting where top brass grill precinct bosses about every last detail of their command—even as he has refined the department's ability to analyze and respond to crime trends."

- ^ Patrol Borough Manhattan South – Report Covering the Week of May 5, 2009 through 05/10/2009 (PDF), New York City Police Department CompStat, May 30, 2009. Accessed May 30, 2009 and Patrol Borough Manhattan North – Report Covering the Week of April 30, 2007 Through 05/06/2007 (PDF), New York City Police Department CompStat, May 30, 2009. Accessed May 30, 2009

- ^ Great Fire of 1776, City University of New York. Accessed April 30, 2007. "Some of Washington's advisors suggested burning New York City so that the British would gain little from its capture. This idea was abandoned and Washington withdrew his forces from the city on September 12, 1776. Three days later the British occupied the city and on September 21, a fire broke out in the Fighting Cocks Tavern. Without the city's firemen present and on duty, the fire quickly spread. A third of the city burnt and 493 houses destroyed."

- ^ Building the Lower East Side Ghetto[dead link]. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ a b Peterson, Iver. "Tenements of 1880s Adapt to 1980s", The New York Times, January 3, 1988, accessed June 30, 2009. "Usually five stories tall and built on a 25-foot (7.6 m) lot, their exteriors are hung with fire escapes and the interiors are laid out long and narrow—in fact, the apartments were dubbed railroad flats."

- ^ White, Jeremy B. (October 21, 2010). "NYDaily News: Rent too damn high?-news". New York. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Morgan Brennan (March 22, 2013). "The World's Most Expensive Cities for Luxury Real Estate". Forbes. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ Are Manhattan's Right Angles Wrong, by Christopher Gray

- ^ "New York City Map". NYC.gov. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ Remarks of the Commissioners for laying out streets and roads in the City of New York, under the Act of April 3, 1807, Cornell University. Accessed May 2, 2007. "These streets are all sixty feet wide except fifteen, which are one hundred feet wide, viz.: Numbers fourteen, twenty-three, thirty-four, forty-two, fifty-seven, seventy-two, seventy-nine, eighty-six, ninety-six, one hundred and six, one hundred and sixteen, one hundred and twenty-five, one hundred and thirty-five, one hundred and forty-five, and one hundred and fifty-five—the block or space between them being in general about two hundred feet."

- ^ a b Silverman, Justin Rocket (May 27, 2006). "Sunny delight in city sight". Newsday.

'Manhattanhenge' occurs Sunday, a day when a happy coincidence of urban planning and astrophysics results in the setting sun lining up exactly with every east-west street in the borough north of 14th Street. Similar to Stonehenge, which is directly aligned with the summer-solstice sun, "Manhattanhenge" catches the sun descending in perfect alignment between buildings. The local phenomenon occurs twice a year, on May 28 and July 12...

- ^ Sunset on 34th Street Along the Manhattan Grid[dead link], Natural History Special Feature—City of Stars. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ^ The Mannahatta Project, Wildlife Conservation Society, January 1, 2006. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- ^ Highlights of the 2001 National Household Travel Survey, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, United States Department of Transportation. Accessed May 21, 2006.

- ^ "New York City Pedestrian Level of Service Study – Phase I, 2006", New York City Department of City Planning, April 2006, p. 4. Accessed May 17, 2007. "In the year 2000, 88% of workers over 16 years old in the U.S. used a car, truck or van to commute to work, while approximately 5% used public transportation and 3% walked to work.... In Manhattan, the borough with the highest population density (66,940 people/sq mi. in year 2000; 1,564,798 inhabitants) and concentration of business and tourist destinations, only 18% of the working population drove to work in 2000, while 72% used public transportation and 8% walked."

- ^ "Manhattan" (PDF). TSTC.org. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ . "Congestion plan dies". NY1. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ [2], NYC Subway System. Accessed August 4, 2009.

- ^ [3], Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority (New York). Accessed May 11, 2007.

- ^ PATH Frequently Asked Questions, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, accessed April 28, 2007. "PATH will phase out QuickCard once the SmartLink Fare Card is introduced."

- ^ Verena Dobnik (February 7, 2013). "NYC Transit Projects: East Side Access, Second Avenue Subway, And 7 Train Extension (PHOTOS)". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority (New York), accessed August 28, 2012.

- ^ About the NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer 8. "Midair Rescue Lifts Passengers From Stranded East River Tram", The New York Times, April 19, 2006. Accessed February 28, 2008. "The system, which calls itself the only aerial commuter tram in the country, has been featured in movies including City Slickers, starring Billy Crystal; Nighthawks, with Sylvester Stallone; and Spider-Man in 2002."

- ^ The Roosevelt Island Tram[dead link], Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ Facts About the Ferry, New York City Department of Transportation, accessed August 28, 2012. "On a typical weekday, five boats make 109 trips, carrying approximately 65,000 passengers. During rush hours, the ferry runs on a four-boat schedule, with 15 minutes between departures."

- ^ An Assessment of Staten Island Ferry Service and Recommendations for Improvement[dead link] (PDF), New York City Council, November 2004, accessed April 28, 2007. ""Of the current fleet of seven vessels, five boats make 104 trips on a typical weekday schedule".

- ^ Holloway, Lynette. "Mayor to End 50-Cent Fare On S.I. Ferry", The New York Times, April 29, 1997, accessed June 30, 2009. "Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani said yesterday that he would eliminate the 50-cent fare on the Staten Island Ferry starting July 4, saying people who live outside Manhattan should not have to pay extra to travel."

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority, accessed May 17, 2006.

- ^ "Port Authority of New York and New Jersey – George Washington Bridge". The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Bod Woodruff, Lana Zak, and Stephanie Wash (November 20, 2012). "GW Bridge Painters: Dangerous Job on Top of the World's Busiest Bridge". ABC News. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Lincoln Tunnel Historic Overview". Eastern Roads. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Holland Tunnel". National Historic Landmark Quicklinks. National Park Service. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Queens-Midtown Tunnel Historic Overview". Eastern Roads. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "President the 'First' to Use Midtown Tube; Precedence at Opening Denied Hundreds of Motorists", The New York Times, November 9, 1940. p. 19.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip. "A Builder Who Went to Town: Robert Moses Shaped Modern New York, for Better and for Worse", The Washington Post, March 11, 2007, accessed April 30, 2007. "The list of his accomplishments is astonishing: seven bridges, 15 expressways, 16 parkways, the West Side Highway and the Harlem River Drive..."